University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

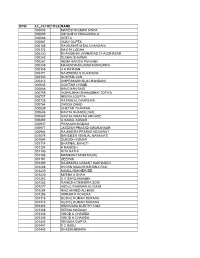

Dpid Lf Cltid Title Name 000006 Mahesh Kumar Sinha 000009

DPID LF_CLTID TITLE NAME 000006 MAHESH KUMAR SINHA 000009 ASHA M CHHANGAWALA 000066 GEETA 000087 VIJAY GUPTA 000105 RAJKUMAR M BALCHANDANI 000174 KAVITA LODHA 000230 BHANUBHAI JAMNADAS CHALISHAZAR 000240 SUMAN SHARMA 000251 HEMA HARISH PUNJABI 000349 MAHENDRAKUMAR KANKERIYA 000355 A H PATHAN 000371 RAJENDRA S SUKHADIA 000380 SUSHMA JAIN 000413 OMPRAKASH BULCHANDANI 000645 GOUTAM CHAND 000668 KANCHAN BAID 000709 GOPALBHAI SHAMJIBHAI TOPIYA 000727 NEERAJ GUPTA 000735 RATANLAL DHAREWA 000764 ZARQA ZAHID 000839 CHETAN THAKKAR 000846 KAVITA KHANDELWAL 000889 SAVITA VINAYAK ARGADE 000892 U KAMAL KUMAR 000937 PRAKASH KODAM 000977 JAGDISH PRASAD SWARANKAR 000984 RAJENDRA PRASAD KEDAWAT 001078 BANSIBEN VENILAL NANAVATI 001084 SUBODH KUMAR 001114 BHATMAL BAHETI 001124 K RAMESH 001145 RITA RATHI 001186 MANIKANT M MATHURE 001191 DEEPAK 001209 RAJENDRA VASANT SAKHADEO 001228 KVGSN MALLIKHARJUNA RAO 001239 KAMAL MUKHERJEE 001240 MEENA K SHAH 001253 D V SAROJINAMMA 001263 RAMESH CHANDRA SONI 001277 ABDUL RAHIMAN ALI BAIG 001284 NIAZ AHMED ALI BAIG 001286 VIKRAM R VOHERA 001316 SUSHIL KUMAR SURANA 001318 SUSHIL KUMAR SURANA 001323 SRINIVASA MURTHY UMA 001328 SEEMA MADAAN 001343 VINOD A CHAWDA 001345 VINOD A CHAWDA 001436 RENUKA GUPTA 001441 K C BABU 001443 SHASHI MISHRA 001458 ASHOK KUMAR GANGWAL 001485 DINESH KUMAR AGARWAL 001491 DEBABRATA SENGUPTA A00016 ABHAY JAIN A00029 AJAY V BHATT A00032 AJIT V MADYE A00038 ALOK KUMAR MAHENSARIA A00046 AMITA TULSYAN A00056 ANANTRAJ ANILKUMAR PATWA A00063 ANIL KUMAR A00067 ANIL KUMAR MAHENSARIA A00073 ANITA MARIA -

HINDUISM in EUROPE Stockholm 26-28 April, 2017 Abstracts

HINDUISM IN EUROPE Stockholm 26-28 April, 2017 Abstracts 1. Vishwa Adluri, Hunter College, USA Sanskrit Studies in Germany, 1800–2015 German scholars came late to Sanskrit, but within a quarter century created an impressive array of faculties. European colleagues acknowledged Germany as the center of Sanskrit studies on the continent. This chapter examines the reasons for this buildup: Prussian university reform, German philological advances, imagined affinities with ancient Indian and, especially, Aryan culture, and a new humanistic model focused on method, objectivity, and criticism. The chapter’s first section discusses the emergence of German Sanskrit studies. It also discusses the pantheism controversy between F. W. Schlegel and G. W. F. Hegel, which crucially influenced the German reception of Indian philosophy. The second section traces the German reception of the Bhagavad Gītā as a paradigmatic example of German interpretive concerns and reconstructive methods. The third section examines historic conflicts and potential misunderstandings as German scholars engaged with the knowledge traditions of Brahmanic Hinduism. A final section examines wider resonances as European scholars assimilated German methods and modeled their institutions and traditions on the German paradigm. The conclusion addresses shifts in the field as a result of postcolonial criticisms, epistemic transformations, critical histories, and declining resources. 2. Milda Ališauskienė, Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania “Strangers among Ours”: Contemporary Hinduism in Lithuania This paper analyses the phenomenon of contemporary Hinduism in Lithuania from a sociological perspective; it aims to discuss diverse forms of Hindu expression in Lithuanian society and public attitudes towards it. Firstly, the paper discusses the history and place of contemporary Hinduism within the religious map of Lithuania. -

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Categorization of Stringed Instruments with Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis

CATEGORIZATION OF STRINGED INSTRUMENTS WITH MULTIFRACTAL DETRENDED FLUCTUATION ANALYSIS Archi Banerjee*, Shankha Sanyal, Tarit Guhathakurata, Ranjan Sengupta and Dipak Ghosh Sir C.V. Raman Centre for Physics and Music Jadavpur University, Kolkata: 700032 *[email protected] * Corresponding Author ABSTRACT Categorization is crucial for content description in archiving of music signals. On many occasions, human brain fails to classify the instruments properly just by listening to their sounds which is evident from the human response data collected during our experiment. Some previous attempts to categorize several musical instruments using various linear analysis methods required a number of parameters to be determined. In this work, we attempted to categorize a number of string instruments according to their mode of playing using latest-state-of-the-art robust non-linear methods. For this, 30 second sound signals of 26 different string instruments from all over the world were analyzed with the help of non linear multifractal analysis (MFDFA) technique. The spectral width obtained from the MFDFA method gives an estimate of the complexity of the signal. From the variation of spectral width, we observed distinct clustering among the string instruments according to their mode of playing. Also there is an indication that similarity in the structural configuration of the instruments is playing a major role in the clustering of their spectral width. The observations and implications are discussed in detail. Keywords: String Instruments, Categorization, Fractal Analysis, MFDFA, Spectral Width INTRODUCTION Classification is one of the processes involved in audio content description. Audio signals can be classified according to miscellaneous criteria viz. speech, music, sound effects (or noises). -

The Written Examination Will Consist of the Following Papers :— Qualifying Papers

MAIN EXAMINATION: The written examination will consist of the following papers :— Qualifying Papers : Paper-A (One of the Indian Language to be selected by the candidate from the Languages included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution). 300 Marks Paper-B English 300 Marks Papers to be counted for merit Paper-I Essay 250 Marks Paper-II General Studies-I 250 Marks (Indian Heritage and Culture, History and Geography of the World and Society) Paper-III General Studies -II 250 Marks (Governance, Constitution, Polity, Social Justice and International relations) Paper-IV General Studies -III 250 Marks (Technology, Economic Development, Bio-diversity, Environment, Security and Disaster Management) Paper-V General Studies -IV 250 Marks (Ethics, Integrity and Aptitude) Paper-VI Optional Subject - Paper 1 250 Marks Paper-VII Optional Subject - Paper 2 250 Marks Sub Total (Written test) 1750 Marks Personality Test 275 Marks Grand Total 2025 Marks Candidates may choose any one of the optional subjects from amongst the list of subjects Government strives to have a workforce which reflects gender balance and women candidates are encouraged to apply. given in para 2 below:— NOTE : The papers on Indian languages and English (Paper A and paper B) will be of Matriculation or equivalent standard and will be of qualifying nature. The marks obtained in these papers will not be counted for ranking. (i) Evaluation of the papers, namely, 'Essay', 'General Studies' and Optional Subject of all the candidates would be done simultaneously along with evaluation of their qualifying papers on ‘Indian Languages’ and ‘English’ but the papers on Essay, General Studies and Optional Subject of only such candidates will be taken cognizance who attain 25% marks in ‘Indian Language’ and 25% in English as minimum qualifying standards in these qualifying papers. -

Physicochemical Assessment and Water Quality of Surface Water in Chandel and Tengnoupal Districts, Manipur for Domestic and Irrigational Uses

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 08 Issue: 01 | Jan 2021 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Physicochemical Assessment and Water Quality of Surface Water in Chandel and Tengnoupal Districts, Manipur for Domestic and Irrigational Uses Herojit Nongmaithem*1, Maibam Pradipkanta Singh2 & Sujata Sougrakpam3 1-3Geological Survey of India, SU: MN, Imphal office, Imphal, 795004 ---------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract: The study aims to validate the water quality for domestic and irrigational uses based on the physico chemical properties of the surface waters in parts of Chandel and Tengnoupal districts of Manipur. The sources of the dissolved constituents in the samples suggest Mg-Ca-HCO3-Cl as the dominant hydro-facies and are magnesium bicarbonate water types. The dominant geochemical process that governs the water chemistry is rock weathering dominance. WQI of the water samples ranges from 76.18 to 155.33 and is well within the limits of the BIS and WHO guidelines for drinking water. All the samples are suitable for irrigational uses based on the determined values of EC, TDS, SSP and SAR. Hence, these perennial rivers and streams hold the potential to provide uninterrupted supply of drinking and irrigational water to Chandel, Tengnoupal, Kakching and Thoubal districts of Manipur without any major treatment. Keywords: Physico-chemical, hydrochemical facies, Water Quality, Manipur 1. Introduction Urbanisation catalyst the human dependency on the water consumption either for domestic or irrigational uses. Rivers and streams show spatial heterogeneity in the physico-chemical indices which enable to categorize the water for different uses or to detect toxicity. -

7 Jan Page 3

Imphal Times Supplementary issue PagePage No. No. 3 3 Clock ticking, Naga talks stuck for long over CM Visits Samadhi of issue of symbols: Report Maharaja Gambhir Singh Agency had been resolved However, it is politically however, did not confirm Naga National Political Dimapur, Jan 7, between the two sides and “unviable for the Centre the same. Groups (NNPGs), a draft agreement was to accept demands such ”I would not like to comprising As the tenure of the NDA ‘almost ready’ by then. as a separate Naga flag, comment on it as we are representatives of six government at the Centre “But a change in Naga even though, sources engaged with the peace influential Naga political nears completion, there is position has led to said, it has agreed to process,” The Indian groups and the National no progress on apprehensions that any guarantee protection of Express’ report said quoting Socialist Council of negotiations for a peace gains made since 2014 will the Naga identity,” it RN Ravi. Nagalim (Isak-Muivah) or accord with Naga armed be lost with a change in added. Ravi has been closely NSCN-IM, had met groups, with talks stuck political dispensation at “But if these changes associated with interlocutors of the for almost a year due to the Centre,” it added. can be brought later negotiations with Naga Central government last an “intransigent position Quoting sources, the through a democratic groups for decades, first in month, and another taken” by the Naga side report said that logjam political process, the various capacities as an meeting is scheduled in on ‘symbolic’ issues, is largely due to issue Centre would have no Intelligence Bureau officer Delhi this month. -

JNEIC Volume 4, Number 2, 2019 | 58 the Dilemma of the Bishnupriya

The Dilemma of the Bishnupriya Identity Naorem Ranjita* Abstract Ethnic identity is a dynamic, multidimensional construct that refers to one's identity, or sense of self, as a member of an ethnic group. The reconstruction of an identity interacts with historical and social identities in the contemporary world. What is intend to discuss in this article is the reconstruction of the Bishnupriya identity in Manipur, and study it against the Bishnupriyas living outside Manipur. The Bishnupriyas remaining in Manipur prefer to be identified as 'Manipuri Meiteis' rather than Bishnupriyas and the logic for this is presumably the perceptions of Bishnupriyas as migrants by the Meiteis. On the other hand, the Bishnupriyas living beyond Manipur, namely in Tripura, Assam, and parts of Bangladesh, would rather be identified as 'Bishnupriya Manipuris', as an attempt to link their identity with the people of Manipur. An observation throughout this paper leads us to reflect upon what the assertion by the Bishnupriyas that 'they' (the Bishnupriyas) are the 'first cultural race' or the 'first settlers' of Manipur and that the Meiteis to be the 'next immigrants'. This speculation has created much doubt and conflict between the Meiteis and the Bishnupriyas. KEYWORDS: Bishnupriya, Meiteis, Manipur Introduction 'The North Eastern part of India is referred to as a melting pot of Mongoloid, Australoid, and Caucasoid populations, which is exhibited in the unique socio-cultural diversity of the region’ (Langstieh et al., 2004: 570). Given the hypothesis that Northeast India is the meeting ground of many diverse culture and population of ethnic and distinctive communities, each unique in its tradition, culture, dress and exotic ways of life, it is evident that migration of people has taken place in different directions. -

Political Structure of Manipur

NAGALAND UNIVERSITY (A Central University Estd. By the Act of Parliament No. 35 of 1989) Headquarters - Lumami. P.O. Makokchung - 79860 I Department of Sociology ~j !Jfo . (J)ate . CER TI FICA TE This is certified that I have supervised and gone through the entire pages of the Ph.D. thesis entitled "A Sociological Study of Political Elite in Manipur'' submitted This is further certified that this research work of Oinam Momoton Singh, carried out under my supervision is his original work and has not been submitted for any degree to any other university or institute. Supervisor ~~ (Dr. Kshetri Rajendra Singh) Associate Professor Place : Lumami. Department of Sociology, Nagaland University Date : '1..,/1~2- Hqs: L\unami .ftssociate <Professor [)eptt of $c".IOI09.Y Neg8'and university HQ:Lumaml DECLARATION The Nagaland University October, 2012. I, Mr. Oinam Momoton Singh, hereby declare that the contents of this thesis is the record of my work done and the subject matter of this thesis did not form the basis of the award of any previous degree to me or to the best of my knowledge to anybody else, and that thesis has not been submitted by me for any research degree in any other university/ institute. This is being submitted to the Nagaland University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology. Candidate ().~~ (OINAM MOMOTON SINGH) Supervisor \~~~I ~~~,__ (PROF. A. LANU AO) (DR. KSHETRI RAJENDRA SINGH) Pro:~· tJeaJ Associate Professor r~(ltt ~ s.-< tr '•'!_)' ~ssociate <Professor f'l;-gts~·'l4i \ "'"~~1·, Oeptt of SodOIOGY Negelend unlY9fSitY HO:Lumeml Preface The theory of democracy tells that the people rule. -

Copyright by Jogendro Singh Kshetrimayum 2011

Copyright by Jogendro Singh Kshetrimayum 2011 The Report Committee for Jogendro Singh Kshetrimayum Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: The Politics of Fixity: A report on the ban of Hindi films in Manipur, Northeast India. APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Kuashik Ghosh Kathleen C. Stewart The Politics of Fixity: A report on the ban of Hindi films in Manipur, Northeast India. by Jogendro Singh Kshetrimayum, M.Sc. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2011 Dedication I dedicate this report to my parents who have always believed in me and Oja Niranjoy who was a passionate teacher and a kind soul. Acknowledgements I thank Tamo Sunil for providing me with valuable insights and information about Manipuri film industry. I also thank him for his time and his efforts to connect me with Manipuri filmmakers, Mukhomani Mongsaba, Lancha and Oken Amakcham. I am very grateful to Maria Luz Garcia, who has been a constant support throughout the different phases of writing this report. Without her constant encouragements it would have been difficult to finish this report. I also thank her for patiently going through my materials and helping me with copyediting. I am grateful to Kathleen Stewart for her comments and suggestions on the report. I thank Kaushik-da for always believing in me. I owe a lot to Kaushik-da for his wonderful insights on a wide range of topics. -

Department of History MODERN COLLEGE, IMPHAL

Department of History MODERN COLLEGE, IMPHAL A. FACULTY BIODATA 1. Personal Profile: Full Name Dr. Pechimayum Pravabati Devi Designation Associate Professor, HOD Date of Birth 01-03-1961 Date of Joining Service 12-10-1990 Subject Specialisation Ancient Indian History Qualification M.A. Ph. D Email [email protected] Contact Number +91 9436284578 Full Name Dr. Moirangthem Imocha Singh Designation Assistant Professor Date of Birth 01-10-1968 Date of Joining Service 16-01-2009 Subject Specialisation Mordern Indian History Qualification M.A. Ph. D Email [email protected] Contact Number 9856148957 Full Name Takhellambam Priya Devi Designation Assistant Professor Date of Birth 10-03-1968 Date of Joining Service 10-05-2016 Subject Specialisation Ancient Indian History Qualification M.A. M. Phil Email [email protected] Contact Number 9862979880 B. Evaluative Report General Information: History Department was open from the establishment of this College since 1963 till today. At present, our Department has three faculty members. Every year around 400 students enrolled in our Department. Sanctioned seat for honours course is 100 of which around 60 students offer honourse. Pass percentage of our Department ranges between 60 to 70 percent. Unit test in the University question pattern are held for every semester, twice for honours students and once for general students. Seminars are compulsory for Honourse students of 5th and 6th semester. Unit test and seminars are not in the ordinance of Manipur University. But in our college, these seminars and unit test are compulsory and held for the betterment of the students. Academic Activity: Faculty members are regularly participated in various academic activities like orientation, refresher course, seminars on international and national level, published books, and presented papers in journals. -

Text and Texture of Clothing in Meetei Community: a Contextual Study

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 2, February 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Text and Texture of Clothing in Meetei Community: A Contextual Study Yumnam Sapha Wangam Apanthoi M* Abstract: This paper is an effort to understand Meetei identity through the text and texture of clothing in ritual context. Meeteis are the majority ethnic group of Manipur, who are Mongoloid in origin. According to the Meetei belief system, they consider themselves as the descendents of Lord Pakhangba, the ruling deity of Manipur. Veneration towards Pakhangba and various beliefs and practices related with the Paphal cult have significantly manifested in the cultural and social spheres of Meetei identity. As part of the material culture, dress plays an important role in manifesting the symbolic representation of their relation with Pakhangba in their mundane life. Meetei cloths are deeply embedded with the socio-cultural meaning of the Meeteiness presented in their oral and verbal expressive behaviors. When seven individual groups merged into one community under the political dominance of Mangang/Ningthouja clan, traditional costume became an important agent in order to recognise the individual identity and the common Meetei identity. There are some cloths which have intricate design with various motifs, believed to be derived from the mark of Pakhangba’s body and are used in order to identify the age, sex, social status, and ethnic identity in ritual context.