Coping with the Coldwar, Global and Domestic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Alasdair Macintyre and Trotskyism

BlackledgeKnight-09_Layout 1 12/29/10 8:07 AM Page 152 9 Alasdair MacIntyre and Trotskyism Alasdair MacIntyre began his literary career in 1953 with Marxism: An Interpretation. According to his own account, in that book he attempted to be faithful to both his Christian and his Marxist beliefs (MacIntyre 1995d). Over the course of the 1960s he abandoned both (MacIntyre 2008k, 180). In 1971 he introduced a collection of his essays by rejecting these and, indeed, all other attempts to illuminate the human condition (MacIntyre 1971b, viii). Since then, MacIntyre has of course re-embraced Christianity, although that of the Catholic Church rather than the An - glicanism to which he originally adhered. It seems unlikely, at this stage, that he will undertake a similar reconciliation with Marxism. Nevertheless, as MacIntyre has frequently reminded his readers, most recently in the prologue to the third edition of After Virtue (2007), his rejection of Marxism as a whole does not entail a rejection of every insight that it has to o ffer. MacIntyre’s current audience tends to be un - interested in his Marxism and consequently remains in ignorance not only of his early Marxist work but also of the context in which it was written. MacIntyre not only wrote from a Marxist perspective but also belonged to a number of Marxist organisations, which, to di ffering de - grees, made political demands on their members from which intellec tu - 152 BlackledgeKnight-09_Layout 1 12/29/10 8:07 AM Page 153 Alasdair MacIntyre and Trotskyism 153 als were not excluded. Even the most insightful of MacIntyre’s admirers tend to treat the subject of these political a ffiliations as an occasion for mild amusement (Knight 1998, 2). -

North Korea and the Theory of the Deformed Workers' State

North Korea and the Theory of the Deformed Workers’ State: Definitions and First Principles of a Fourth International Theory Alzo David-West James P. Cannon, Peng Shuzi, Pierre Frank, Michel Pablo, Ernest Mandel, and Tim Wohlforth Abstract This essay examines the academically neglected theory of the deformed workers’ state in relation to the political character of the North Korean state. Developed by leaders of the Fourth International, the world party of socialism founded by exiled Russian Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky, the theory classifies the national states that arose under post- Second World War Soviet Army occupation as bureaucratic, hybrid, transitional formations that imitated the Soviet Stalinist system. The author reviews the origin of the theory, explores its political propositions and apparent correspondences in the North Korean case, and concludes with some hypotheses and suggestions for further research. Copyright © 2012 by Alzo David-West and Cultural Logic, ISSN 1097-3087 Alzo David-West 2 Introduction On the centenary of the birth of Kim Il Sung in 2012, North Korea entered a period officially designated as “opening the gate to a great prosperous and powerful socialist nation.” Coming after the post-Soviet rise of markets within a planned economy, the initiation of capitalist Special Economic Zones in the early 1990s and 2000s, market- oriented economic and currency reforms in 2002, and the dropping of “communism” from the 2009 revised constitution, the reference to present-day North Korea as a “socialist nation” is evidently more symbolic than substantial. Still, over sixty years after the founding of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) on 9 September 1948, the political character of the North Korean state remains a more or less unresolved issue in North Korean studies. -

Chapter Two Trotsky, the Left Opposition and the Rise of Stalinism: Theory and Practice

Chapter Two Trotsky, the Left Opposition and the Rise of Stalinism: Theory and Practice Introduction This chapter proposes to re-evaluate the political character and historical significance of the Left Oppo- sition through a detailed assessment of Tony Cliff’s Trotsky, 1923–1927: Fighting the Rising Stalinist Bureau- cracy and Trotsky, 1927–1940: The Darker the Night the Brighter the Star, which are, respectively, the third and fourth volumes of his Trotsky biography. In the pages that follow, I argue that Trotsky and the Left Opposition did not oppose Stalin’s policies of forced industrialisation and collectivisation. Worse, they failed to support worker- and peasant-resistance to these policies. In fact, the political programme and worldview of the Left Opposition objectively con- tributed to the formation and consolidation ‘from above’ of a new class-society in the critical period of 1927–33. The visceral reaction of many Marxists and per- haps all Trotskyists to anyone brazen or foolish enough to declare the traditional understanding of the Left Opposition’s historical role incorrect might be to consider it absurd. And yet, none other than Cliff, in his comprehensive and probing study of Trotsky’s life and politics, recognised this cardinal fact: the overwhelming majority of the Left Oppo- sition’s leadership believed that ‘Stalin’s policies of collectivisation and speedy industrialisation were 88 • Chapter Two socialist policies, that there was no realistic alternative to them.’1 But if this was so – and it was so – how can this disturbing fact be reconciled with any notion that, at this critical juncture, Trotsky and the Left Opposition were ‘fighting the rising Stalinist bureaucracy’ and its policies? Cliff thought he could get around this contradiction by arguing that Trotsky kept up the fight while the Left Opposition ‘capitulated’ to Stalin. -

Trotskyism Emerges from Obscurity: New Chapters in Its Historiography

IRSH 49 (2004), pp. 279–292 DOI: 10.1017/S002085900400152X # 2004 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis REVIEW ESSAY Trotskyism Emerges from Obscurity: New Chapters in Its Historiography Jan Willem Stutjeà Bensaı¨d,Daniel. Les trotskysmes. Deuxie`me e´d. [Que sais-je?, 3629.] Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 2002. 128 pp. A 6.50. Charpier, Fre´de´ric. Histoire de l’extreˆme gauche trotskiste. De 1929 a` nos jours. Editions 1, Paris 2002. 402 pp. A 22.00. Marie, Jean-Jacques. Le trotskysme et les trotskystes. D’hier a` au- jourd’hui, l’ideologie et les objectifs des trotskystes a` travers le monde. [Collection L’Histoire au present.] Armand Colin, Paris 2002. 224 pp. A 21.00. Nick, Christophe. Les Trotskistes. Fayard, [Paris] 2003. 618 pp. A 23.00. The Trotskyist Fourth International went through many quarrels and splits after its foundation in 19381 – understandably, given the political and social isolation in which the movement generally functioned. Its enemies to its left and right crowded the Trotskyists into an uncomfor- tably narrow space. Trotskyists’ intense internal discussions functioned as a sort of immune response, which could only be effective if theoretical and à Jan Willem Stutje is working on a biography of Ernest Mandel (a project of the Free University of Brussels under the supervision of Professor E. Witte) with support from the Flemish Fund for Scholarly Research. 1. For bibliographies of Leon Trotsky and Trotskyism, see Louis Sinclair, Trotsky: a Bibliography (Aldershot, 1989); Wolfgang and Petra Lubitz (eds), Trotsky Bibliography: An International Classified List of Publications About Leon Trotsky and Trotskyism 1905–1998, 3rd compl. -

In Defence of Trotskyism No.2

In Defence of Trotskyism Price: Waged: £2.00, 3€ Concessions: 50p, Number 2 Summer 2011 Imperialism’s offensive against the world’s working class has sharply intensified since the credit crunch crisis began in 2008. Hand in hand with this goes the offensive against the ideol- ogy of global working class liberation, revolutionary Trotskyism. The political and ideological collapse of all the soft left groups who refuse to call for an anti-Imperialist United Front with- out political support with Gaddafi and who continue to back the counter-revolutionary rebels of Benghazi and demand the overthrow of Gaddafi on behalf of Imperialism is shocking. Today new ideologues and renegades join the old swamp of opportunism; Karl Kautsky finds a new champion in Lars T Lih. Max Shachtman and Raya Dunayevskaya, previously only de- fended by Sean Matgamna, find new adherents in Cyril Smith, The Commune, Permanent Revolution, the Movement for Socialism, etc. István Mészáros and Cliff Slaughter et al seek to trump the Bolshevism of Lenin and Trotsky with the counter-revolutionary reformist dross of history from the likes of Kautsky. IDOT does battle with all these petty bourgeois ideologues, enemies of humanity's communist future. Bibliography In Defence of Trotskyism is published by the Socialist Fight Group. Contact: PO Box 59188, London, NW2 9LJ. Email: [email protected] đoàn kết là ,اتحاد قدرت است . ,Unity is strength, L'union fait la force, Es la unidad fuerza, Η ενότητα είναι δύναμη sức mạnh, Jedność jest siła, ykseys on kesto, યુનિટિ થ્રૂ .િા , Midnimo iyo waa awood, hundeb ydy chryfder, Einheit ist unità è la ,אחדות היא כוח ,Stärke, एकता शक्ति, है единстве наша сила, vienybės jėga, bashkimi ben fuqine Ní neart go ,الوحدة هو القوة ,resistenza, 団結は力, A unidade é a força, eining er styrkur, De eenheid is de sterkte chur le céile, pagkakaisa ay kalakasan, jednota is síla, 일성은 이다 힘 힘, Workers of the World Unite! In Defence of Trotskyism page 2 Revolution. -

Lenin Reloaded

Lenin Reloaded SIC stands for psychoana- lytic interpretation at its most elementary: no dis- covery of deep, hidden meaning, just the act of drawing attention to the litterality [sic!] of what pre- cedes it. A “sic” reminds us that what was said, in- clusive of its blunders, was effectively said and cannot be undone. The series SIC thus explores different connections to the Freud- ian field. Each volume pro- vides a bundle of Lacanian interventions into a spe- cific domain of ongoing theoretical, cultural, and SIC ideological-political battles. It is neither “pluralist” A nor “socially sensitive”: series unabashedly avowing its exclusive Lacanian orienta- edited tion, it disregards any form by of correctness but the inherent correctness of Slavoj theory itself. Žižek Lenin Toward a Politics of Truth Reloaded Sebastian Budgen, Stathis Kouvelakis, and Slavoj Žižek, editors sic 7 DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS Durham and London 2007 © 2007 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ♾ Typeset in Sabon by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Sebastian Budgen, Stathis Kouvelakis, and Slavoj Žižek, Introduction: Repeating Lenin 1 PART I. RETRIEVING LENIN 1 Alain Badiou, One Divides Itself into Two 7 2 Alex Callinicos, Leninism in the Twenty-first Century?: Lenin, Weber, and the Politics of Responsibility 18 3 Terry Eagleton, Lenin in the Postmodern Age 42 4 Fredric Jameson, Lenin and Revisionism 59 5 Slavoj Žižek, A Leninist Gesture Today: Against the Populist Temptation 74 PART II. -

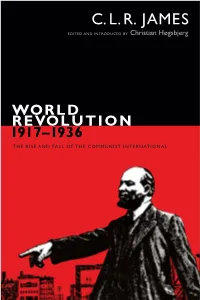

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED and INTRODUCED by Christian Høgsbjerg

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY Christian Høgsbjerg WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 THE RISE AND FALL OF THE COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 ||||| C. L. R. James in Trafalgar Square (1935). Courtesy of Getty Images. the c. l. r. james archives recovers and reproduces for a con temporary audience the works of one of the great intel- lectual figures of the twentiethc entury, in all their rich texture, and will pres ent, over and above historical works, new and current scholarly explorations of James’s oeuvre. Robert A. Hill, Series Editor WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 The Rise and Fall of the Communist International ||||| C. L. R. J A M E S Edited and Introduced by Christian Høgsbjerg duke university press Durham and London 2017 Introduction and Editor’s Note © 2017 Duke University Press World Revolution, 1917–1936 © 1937 C. L. R. James Estate Harry N. Howard, “World Revolution,” Annals of the American Acad emy of Po liti cal and Social Science, pp. xii, 429 © 1937 Pioneer Publishers E. H. Carr, “World Revolution,” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1931–1939) 16, no. 5 (September 1937), 819–20 © 1937 Wiley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Arno Pro and Gill Sans Std by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: James, C. L. R. (Cyril Lionel Robert), 1901–1989, author. | Høgsbjerg, Christian, editor. Title: World revolution, 1917–1936 : the rise and fall of the Communist International / C. L. R. James ; edited and with an introduction by Christian Høgsbjerg. -

THE MAKING of a PARTY? the International Socialists 1965-1 976

THE MAKING OF A PARTY? The International Socialists 1965-1 976 Martin Shaw The history of organised marxist politics in Britain, for almost a century, is one of continuous marginality. The number of people involved in marxist parties and organisations of any description has never exceeded a few tens of thousands at any one time. The problem of creating a socialist organisation of real political weight, to the left of the Labour Party, might well seem insoluble. Many have concluded, indeed, that this is so; from the leadership of the Communist Party, with its desire for long-term merger with Labour, and the deep-entry trotskyists of Militant to the thousands of ex-Communists and revolutionary socialists who have joined the Labour Party as individuals. The overall record of failure should not blind us, however, to the real opportunities which have been lost due to the inadequacies of the marxist left itself. To give only the most important example, early British marxism was dominated by a sectarian propagandist tradition, which greatly militated against its achieving any decisive influence, either in the formative period of the modern labour movement, or in the great industrial upheavals just before, during and after the 1914-18 war. Nor should this record allow us to assume that the underlying features of British working-class politics, which have made for the unique dominance of Labourist reformism in the last three-quarters of a century, will never change. On the contrary, there are reasons for believing that they have already begun to be transformed. The 1945-51 period of Labour Government was, in fact, a watershed in working-class politics. -

The Return of Stalinism? 51 John Molyneux

The Return of Stalinism? 51 John Molyneux Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world- to revisit the question of Stalinism: to examine the historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, nature of the beast and assess the role it has played twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, internationally and in Ireland. the second time as farce... The tradition of all dead To assess Stalinism as a historical phenomenon, we generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of first need to recognise that it has various manifestations the living. and that, while these are all related to one another, Karl Marx, Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis they are by no means all ‘the same’. I would distinguish Bonaparte. the following main categories: 1) Stalinism in Russia under Stalin, known as ‘high Stalinism’;2) Comintern hen the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 with Stalinism; 3) Stalinism after Stalin in Russia and Eastern the fall of the ‘Communist’ regimes in Eastern Europe; 4) Stalinism in the Third World (China, Cuba Europe and the Soviet Union collapsed soon etc.). I will look at them in turn and then say something after in 1991, Stalinism, together with socialism about the specific role of Stalinism in Ireland. Because Win general, was widely pronounced dead. The death this necessitates covering a vast amount of history on of Stalinism was proclaimed not only by the right but an international scale, it will not be possible in one by many on the left who hoped that its demise would article to offer detailed substantiation for all the points clear the way for a genuine socialism from below. -

Trotsky: Vol. 1. Towards October 1879-1917

Trotsky: Towards October 1879-1917 Tony Cliff Bookmarks, London, 1989. Transcribed by Martin Fahlgren (July 2009) Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists Internet Archive Converted to ebook format June 2020 Cover photograph: Mug shot from Russian secret police files, 1900. Marxists Internet Archive At the time of ebook conversion this title was out of print. Other works of Tony Cliff are available in hardcopy from: https://bookmarksbookshop.co.uk/ Contents Preface 1. Youth Revolutionary Agitator and Organiser In Prison and Siberia 2. Meeting Lenin Under the Spell of the Veterans 3. The 1903 Congress Trotsky and Factional Disputes The Beginning of Congress Marxism, Jacobinism and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat Lenin Versus Martov on Party Rules. Trotsky Supports Martov Split on the Composition of Iskra’s Editorial Board Attitude to the Liberals 4. Vigorous Assault on Lenin Trotsky’s Report of the Siberian Delegation Trotsky’s Estrangement From the Mensheviks On Substitutionism For a Broad Mass Party Again on Bolshevism and Jacobinism 5. An Explanation of the Break Between Lenin and Trotsky Trotsky’s Experience of 1905 and Conciliationism Trotsky and the Committee-Men Rosa Luxemburg’s Opposition to Lenin’s Concept of the Party In Conclusion 6. Trotsky and Parvus: The Inception of the Theory of Permanent Revolution Up to the 9th January Parvus on the Prospects of Russian Revolution 7. The 1905 Revolution Beginning of the Revolution The October General Strike and the Emergence of the Petersburg Soviet The Tsar’s October Manifesto Pogroms Soviet Conquers Press Freedom The November General Strike The Struggle for the Eight-Hour Day Impact on the Peasantry On the Armed Insurrection The Soviet – Embryo of Workers’ Government The Soviet’s Last Gesture The End of the Soviet Precursor Mensheviks Under the Heady Influence of Trotsky In His Element 8. -

Aufheben What Was the USSR?

Aufheben What was the USSR? What was the USSR? Part I: Trotsky and State Capitalism What was the USSR? Part II: Russia as a Non-mode of Production What was the USSR? Part III: Left communism and the Russian revolution What was the USSR? Part IV: Towards a Theory of the Deformation of Value What was the USSR? Part I: Trotsky and state capitalism The Russian Revolution and the subsequent establishment of the USSR as a 'workers' state', has dominated political thinking for more than three generations. In the past, it seemed enough for communist revolutionaries to define their radical separation with much of the 'left' by denouncing the Soviet Union as state capitalist. This is no longer sufficient, if it ever was. Many Trotskyists, for example, now feel vindicated by the 'restoration of capitalism' in Russia. To transform society we not only have to understand what it is, we also have to understand how past attempts to transform it failed. In this and future issues we shall explore the inadequacies of the theory of the USSR as a degenerated workers' state and the various versions of the theory that the USSR was a form of state capitalism. Introduction The question of Russia once more In August 1991 the last desperate attempt was made to salvage the old Soviet Union. Gorbachev, the great reformer and architect of both Glasnost and Perestroika, was deposed as President of the USSR and replaced by an eight man junta in an almost bloodless coup. Yet, within sixty hours this coup had crumbled in the face of the opposition led by Boris Yeltsin, backed by all the major Western powers.