Saints' Relics in Medieval English Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I WRITING MIRACLES in TENTH-CENTURY WINCHESTER

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository WRITING MIRACLES IN TENTH-CENTURY WINCHESTER by Cory Stephen Hazlehurst A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Medieval History College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham February 2011 i University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines a number of miracle collections and hagiographies written by Winchester monks in the late tenth century. It compares three different accounts of the cult of Swithun by Lantfred, Wulfstan and Ӕlfric, as well as comparing Wulfstan‟s and Ӕlfric‟s Vita Ӕthelwoldi. There were two main objectives to the thesis. The first was to examine whether an analysis of miracle narratives could tell us anything important about how a monastic community perceived itself, especially in relation to the wider world? This was tested by applying approaches used by Thomas Head and Raymond Van Dam to an Anglo- Saxon context. -

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

A History of Darwin's Parish Downe, Kent

A HISTORY OF DARWIN’S PARISH DOWNE, KENT BY O. J. R. HOW ARTH, Ph.D. AND ELEANOR K. HOWARTH WITH A FOREWORD BY SIR ARTHUR KEITH, F.R.S. SOUTHAMPTON : RUSSELL & CO. (SOUTHERN COUNTIES) LTD. CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE Foreword. B y Sir A rthur K eith, F.R.S. v A cknowledgement . viii I Site and P re-history ..... i II T he E arly M anor ..... 7 III T he Church an d its R egisters . 25 IV Some of t h e M inisters ..... 36 V Parish A ccounts and A ssessments . 41 VI T he People ....... 47 V II Some E arly F amilies (the M annings and others) . - 5 i VIII T he L ubbocks, of Htgh E lms . 69 IX T he D arwtns, of D own H ouse . .75 N ote on Chief Sources of Information . 87 iii FOREWORD By S ir A rth u r K e it h , F.R .S. I IE story of how Dr. Howarth and I became resi T dents of the parish of Downe, Kent— Darwin’s parish— and interested in its affairs, both ancient and modern, begins at No. 80 Wimpole Street, the home of a distinguished surgeon, Sir Buckston Browne, on the morning of Thursday, September 1, 1927. On opening The Times of that morning and running his eye over its chief contents before sitting down to breakfast, Sir Buck ston observed that the British Association for the Ad vancement of Science—of which one of the authors of this book was and is Secretary— had assembled in Leeds and that on the previous evening the president had delivered the address with which each annual meeting opens. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900 Hancock, Christopher David How to cite: Hancock, Christopher David (1984) The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7473/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 VOLUME II 'THE PRIESTHOOD OF CHRIST IN ANGLICAN DOCTRINE AND DEVOTION: 1827 -1900' BY CHRISTOPHER DAVID HANCOCK The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Durham, Department of Theology, 1984 17. JUL. 1985 CONTENTS VOLUME. II NOTES PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER I 26 CHAPTER II 46 CHAPTER III 63 CHAPTER IV 76 CHAPTER V 91 CHAPTER VI 104 CHAPTER VII 122 CHAPTER VIII 137 ABBREVIATIONS 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 1 NOTES PREFACE 1 Cf. -

Letters from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, (NLW MS 12877C.)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Letters from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, (NLW MS 12877C.) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 08, 2017 Printed: May 08, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/letters-from-arthur-penrhyn-stanley archives.library .wales/index.php/letters-from-arthur-penrhyn-stanley Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Letters from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 3 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points ............................................................................................................... 4 Llyfryddiaeth | Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... -

The Reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three Minor Revisions

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2001 The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions John Donald Hosler Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Hosler, John Donald, "The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions" (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 21277. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/21277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions by John Donald Hosler A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Major Professor: Kenneth G. Madison Iowa State University Ames~Iowa 2001 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of John Donald Hosler has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 The liberal arts had not disappeared, but the honours which ought to attend them were withheld Gerald ofWales, Topograhpia Cambria! (c.1187) IV TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION 1 Overview: the Reign of Henry II of England 1 Henry's Conflict with Thomas Becket CHAPTER TWO. -

Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2012 The nbU ought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N. Boggs Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boggs, Richard N., "The nbouU ght Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature" (2012). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 21. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/21 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Mentor: Dr. Thomas Cook Reader: Dr. Gail Sinclair Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature By Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Project Approved: ________________________________________ Mentor ________________________________________ Reader ________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Dedicated to my wife Elizabeth for her love, her patience and her unceasing support. CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Greek Pre-Chivalry 5 III. Roman Pre-Chivalry 11 IV. The Rise of Christian Chivalry 18 V. The Age of Chivalry 26 VI. -

The Saxon Cathedral at Canterbury and the Saxon

1 29 078 PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER THE SAXON CATHEDRAL AT" CANTERBURY AND THE SAXON SAINTS BURIED THEREIN Published by the University of Manchester at THE UNIVERSITY PRESS (H. M. MCKECHNIE, M.A., Secretary) 23 LIME GROTE, OXFORD ROAD, MANCHESTER THE AT CANTEViVTHESAXg^L CATHEDRAL SAXON SAINTS BURIED THEffilN BY CHARLES COTTON, O.B.E., F.R.C.P.E. Hon. Librarian, Christ Church Cathedral, Canterbury MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 1929 MADE IN ENGLAND Att rights reserved QUAM DILECTA TABERNACULA How lovely and how loved, how full of grace, The Lord the God of Hosts, His dwelling place! How elect your Architecture! How serene your walls remain: Never moved by, Rather proved by Wind, and storm, and surge, and rain! ADAM ST. VICTOR, of the Twelfth Century. Dr. J. M. Neale's translation in JMediaval Hymns and Sequences. PREFACE account of the Saxon Cathedral at Canterbury, and of the Saxon Saints buried therein, was written primarily for new THISmembers of Archaeological Societies, as well as for general readers who might desire to learn something of its history and organiza- tion in those far-away days. The matter has been drawn from the writings of men long since passed away. Their dust lies commingled with that of their successors who lived down to the time when this ancient Religious House fell upon revolutionary days, who witnessed its dissolution as a Priory of Benedictine Monks after nine centuries devoted to the service of God, and its re-establishment as a College of secular canons. This important change, taking place in the sixteenth century, was, with certain differences, a return to the organization which existed during the Saxon period. -

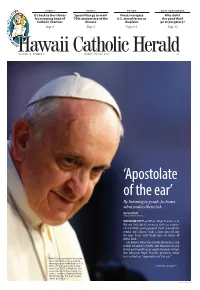

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’S Back to the Islands Special Liturgy to Mark Priests Navigate Why Didn’T for Incoming Head of 75Th Anniversary of the U.S

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’s back to the Islands Special liturgy to mark Priests navigate Why didn’t for incoming head of 75th anniversary of the U.S. armed forces as the good thief Catholic Charities diocese chaplains go to purgatory? Page 3 Page 5 Page 8-9 Page 12 HVOLUME 79,awaii NUMBER 14 CatholicFRIDAY, JULY 29, 2016 Herald$1 ‘Apostolate of the ear’ By listening to youth, he hears what makes them tick By Carol Glatz Catholic News Service VATICAN CITY — When Pope Francis is in Poland July 26-31 to meet with an expect- ed 2 million young people from around the world, he’s there with a firm idea of the dreams, fears and challenges so many of them face. He knows what lies inside the hearts and minds of today’s youth, not because of any third-party polling or sophisticated survey, but because Pope Francis practices what he’s called an “apostolate of the ear.” Pope Francis is pictured leaving an encounter with young people in the piazza outside the Basilica of St. Mary of the Angels in Assisi, Italy, Continued on page 10 in this Oct. 4, 2013, file photo. The pope plans to visit Assisi Aug. 4 to make a “simple and private” visit to the Portiuncola, the stone chapel rebuilt by St. Francis. CNS photo/Paul Haring 2 HAWAII HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD • JULY 29, 2016 Official notices Hawaii Bishop’s calendar Bishop’s Schedule [Events indicated will be attended by Bishop’s Catholic delegate] Herald July 25-31, World Youth Day, Kraków, Poland. -

St Cuthbert Story

Cuthbert was born about the year 634 (about 1400 years ago!) He lived in Melrose in Southern Scotland. He liked to walk in the hills. One night, when he was helping to look after sheep he thought he saw angels taking a soul to heaven. A few days later he found out Saint Aidan had died. Cuthbert decided to become a monk. He became a monk at the monastery in Melrose where he met Boisil, the prior of the monastery. Boisil taught Cuthbert for 6 years. Before Boisil died, he told Cuthbert he would be a Bishop one day. Cuthbert liked to visit lonely farms and villages. Crowds of people came to visit him. He lived at Melrose monastery for 13 years. Cuthbert was sent to be Prior of Lindisfarne. Cuthbert taught the monks the new Roman church rules. Some of the monks did not like the new rules and Cuthbert had to be very patient with them. After 12 years, Cuthbert went to live on a quiet island 7 miles away from Lindisfarne. Cuthbert lived on this small island for 3 years. He grew barley and vegetables and his monks dug a well and built a guest house for visitors. The King asked Cuthbert to be Bishop of Hexham. Cuthbert didn’t want to but he still remembered what Boisil had said. Cuthbert did not want to be Bishop of Hexham but agreed to be Bishop of Lindisfarne instead. He was very sad to have to leave his small island. Cuthbert was Bishop of Lindisfarne for 2 years. The people loved him. -

22, 2017 Hawai'i Convention Center

2017 DAMIEN AND MARIANNE CATHOLIC CONFERENCE October 20 – 22, 2017 Hawai’i Convention Center CONFERENCE SCHEDULE Friday, October 20 Saturday, October 21 Sunday, October 22 Exhibit Hall Open Registration Check-in Registration Check-In 8:00am 7:00am 7:30am Registration Check-In Exhibit Hall Open Exhibit Hall Open Opening Ceremony 10:00am 8:30am Tongan Mass 8:30am Rosary Keynote Speaker 10:30am 10:00am Keynote Speaker 9:00am Keynote Speaker Lunch Break 12:15pm 11:15am Breakout Sessions 10:30am Performing Arts Play Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 12:30pm 12:15pm Lunch Break 12:15pm Lunch Break Reconciliation Prayer Service – Divine Mercy Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 3:00pm 12:30pm 1:00pm Closing Mass Chaplet Reconciliation Welcome from Bishop Larry Silva 1:45pm & 3:45pm Breakout Sessions Hawaiian Mass 3:00pm Dinner Break 5:00pm 4:00pm Dinner Break Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 5:00pm 4:00pm Reconciliation Reconciliation Keynote Speaker 7:00pm 7:15pm Breakout Sessions Youth Activities 8:00pm 8:30pm Concert Conference Sessions and Prayer Service Friday, October 20 10:00am 3:00pm – 5:00pm OPENING CEREMONY & SAINTS AWARD DIVINE MERCY CHAPLET Oli Prayer acknowledging Ke Akua, those who are present, and the In 1935, St. Faustina received a vision of an angel sent by God to reason for the gathering. chastise a certain city. She began to pray for mercy, but her prayers were powerless. Suddenly she saw the Holy Trinity and felt the 10:30am – 11:30am power of Jesus’ grace within her. At the same time she found P101 EXTRAORDINARY VISIONS! herself pleading with God for mercy with words she heard interiorly. -

Masculinity and Chivalry: the Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature

MASCULINITY AND CHIVALRY: THE TENUOUS RELATIONSHIP OF THE SACRED AND SECULAR IN MEDIEVAL ARTHURIAN LITERATURE by KACI MCCOURT DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2018 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Kevin Gustafson, Supervising Professor Jacqueline Fay James Warren i ABSTRACT Masculinity and Chivalry: The Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature Kaci McCourt, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2018 Supervising Professors: Kevin Gustafson, Jacqueline Fay, and James Warren Concepts of masculinity and chivalry in the medieval period were socially constructed, within both the sacred and the secular realms. The different meanings of these concepts were not always easily compatible, causing tensions within the literature that attempted to portray them. The Arthurian world became a place that these concepts, and the issues that could arise when attempting to act upon them, could be explored. In this dissertation, I explore these concepts specifically through the characters of Lancelot, Galahad, and Gawain. Representative of earthly chivalry and heavenly chivalry, respectively, Lancelot and Galahad are juxtaposed in the ways in which they perform masculinity and chivalry within the Arthurian world. Chrétien introduces Lancelot to the Arthurian narrative, creating the illicit relationship between him and Guinevere which tests both his masculinity and chivalry. The Lancelot- Grail Cycle takes Lancelot’s story and expands upon it, securely situating Lancelot as the best secular knight. This Cycle also introduces Galahad as the best sacred knight, acting as redeemer for his father. Gawain, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, exemplifies both the earthly and heavenly aspects of chivalry, showing the fraught relationship between the two, resulting in the emasculating of Gawain.