Neoliberalism Mark Lowes Proofs 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS RELEASE FIM Grand Prix World Championship

PRESS RELEASE MIES, 29/05/2020 FOR MORE INFORMATION: ISABELLE LARIVIÈRE COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER [email protected] TEL +41 22 950 95 68 FIM Grand Prix World Championship 2020 Calendar, UPDATE 29 MAY British and Australian Grands Prix cancelled The FIM, IRTA and Dorna Sports regret to announce the cancellation of the British and Australian Grands Prix. The ongoing coronavirus outbreak and resulting calendar changes have obliged the cancellation of both events. The British Grand Prix was set to take place from 28 to 30 August at the classic Silverstone Circuit. Silverstone hosted the first Grands Prix held on the British mainland from 1977, and MotoGP™ returned to the illustrious track ten years ago. 2020 will now sadly mark the first year MotoGP™ sees no track action in the British Isles for the first time in the Championship’s more than 70-year history. The Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix was set to take place at the legendary Phillip Island Grand Prix Circuit from 23 to 25 October. Phillip Island hosted the very first Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix in 1989 and since 1997 has been the only home of MotoGP™ Down Under - with its unique layout providing some of the greatest battles ever witnessed on two wheels. The cancellation of the British Grand Prix also obliges the cancellation of the corresponding British Talent Cup track activity at the same event. Stuart Pringle, Silverstone Managing Director: “We are extremely disappointed about the cancellation of the British MotoGP event, not least as the cancelled race in 2018 is still such a recent memory, but we support the decision that has had to be taken at this exceptional time. -

A 'Common-Sense Revolution'? the Transformation of the Melbourne City

A ‘COMMON-SENSE REVOLUTION’? THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE MELBOURNE CITY COUNCIL, 1992−9 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April, 2015 Angela G. Munro Faculty of Business, Government and Law Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is the culmination of almost fifty years’ interest professionally and as a citizen in local government. Like many Australians, I suspect, I had barely noticed it until I lived in England where I realised what unique attributes it offered, despite the different constitutional arrangements of which it was part. The research question of how the disempowerment and de-democratisation of the Melbourne City Council from 1992−9 was possible was a question with which I had wrestled, in practice, as a citizen during those years. My academic interest was piqued by the Mayor of Stockholm to whom I spoke on November 18, 1993, the day on which the Melbourne City Council was sacked. ‘That couldn’t happen here’, he said. I have found the project a herculean labour, since I recognised the need to go back to 1842 to track the institutional genealogy of the City Council’s development in the pre- history period to 1992 rather than a forensic examination of the seven year study period. I have been exceptionally fortunate to have been supervised by John Halligan, Professor of Public Administration at University of Canberra. An international authority in the field, Professor Halligan has published extensively on Australian systems of government including the capital cities and the Melbourne City Council in particular. -

Letter from Melbourne Is a Monthly Public Affairs Bulletin, a Simple Précis, Distilling and Interpreting Mother Nature

SavingLETTER you time. A monthly newsletter distilling FROM public policy and government decisionsMELBOURNE which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. Saving you time. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. p11-14: Special Melbourne Opera insert Issue 161 Our New Year Edition 16 December 2010 to 13 January 2011 INSIDE Auditing the state’s affairs Auditor (VAGO) also busy Child care and mental health focus Human rights changes Labor leader no socialist. Myki musings. Decision imminent. Comrie leads Victorian floods Federal health challenge/changes And other big (regional) rail inquiry HealthSmart also in the news challenge Baillieu team appointments New water minister busy Windsor still in the news 16 DECEMBER 2010 to 13 JANUARY 2011 14 Collins Street EDITORIAL Melbourne, 3000 Victoria, Australia Our government warming up. P 03 9654 1300 Even some supporters of the Baillieu government have commented that it is getting off to a slow F 03 9654 1165 start. The fact is that all ministers need a chief of staff and specialist and other advisers in order to [email protected] properly interface with the civil service, as they apply their new policies and different administration www.letterfromcanberra.com.au emphases. These folk have to come from somewhere and the better they are, the longer it can take for them to leave their current employment wherever that might be and settle down into a government office in Melbourne. Editor Alistair Urquhart Some stakeholders in various industries are becoming frustrated, finding it difficult to get the Associate Editor Gabriel Phipps Subscription Manager Camilla Orr-Thomson interaction they need with a relevant minister. -

THE FAMOUS FACES WHO HELPED INSPIRE a GREAT KNIGHT for the Past 25 Years, GRANT Mcarthur Keating and Malcolm Hewitt Screaming “C’Mon”

06 NEWS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 8, 2015 HERALDSUN.COM.AU ALWAYS MAKING HEADLINES Melbourne legends, stars mark our milestone IT was aptly a headline- NUI TE KOHA, outed him and then-girlfriend a great move and it’s just gone grabbing event celebrating the JACKIE EPSTEIN Holly before they had gone on from strength to strength. I’m 25-year milestone of a news AND LUKE DENNEHY a second date. really honoured to be part of powerhouse. “We hadn’t had that chat,” this celebration ... It’s such a big About 350 prominent Mel- Television legend Newton Hughes said. part of Melbourne.” burnians gathered to honour said: “Melbourne is a great city Holly, a journalist, started Celebrity guests were in a the Herald Sun at a star-stud- but it’s made even better by working at the Herald Sun as a cheeky mood when photogra- ded party at The Emerson in institutions like the Herald Sun. “beautiful 22 year old,” he said. phers tried to get a shot of the South Yarra last night. “I can’t imagine Melbourne “For 10 years, not one editor assembled throng. Powerbrokers, including without it. hit on her. What is going on “(Jeff) Kennett will break Eddie McGuire, Michael Gud- “I’m a Melbourne boy, born there?” Hughes said. the camera,” John Elliott bel- inski, Jeanne Pratt, Robert and bred, and the Herald Sun is He said media mogul Ru- lowed. Doyle and Jeff Kennett, joined one of the important traditions pert Murdoch insisted Colling- Kennett retorted: “The legends, like Ian “Molly” Mel- of living here.” wood”s 1990 premiership win camera will break itself. -

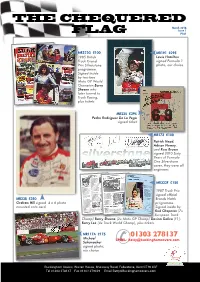

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

1 Heat Treatment This Is a List of Greenhouse Gas Emitting

Heat treatment This is a list of greenhouse gas emitting companies and peak industry bodies and the firms they employ to lobby government. It is based on data from the federal and state lobbying registers.* Client Industry Lobby Company AGL Energy Oil and Gas Enhance Corporate Lobbyists registered with Enhance Lobbyist Background Limited Pty Ltd Corporate Pty Ltd* James (Jim) Peter Elder Former Labor Deputy Premier and Minister for State Development and Trade (Queensland) Kirsten Wishart - Michael Todd Former adviser to Queensland Premier Peter Beattie Mike Smith Policy adviser to the Queensland Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, LHMU industrial officer, state secretary to the NT Labor party. Nicholas James Park Former staffer to Federal Coalition MPs and Senators in the portfolios of: Energy and Resources, Land and Property Development, IT and Telecommunications, Gaming and Tourism. Samuel Sydney Doumany Former Queensland Liberal Attorney General and Minister for Justice Terence John Kempnich Former political adviser in the Queensland Labor and ACT Governments AGL Energy Oil and Gas Government Relations Lobbyists registered with Government Lobbyist Background Limited Australia advisory Pty Relations Australia advisory Pty Ltd* Ltd Damian Francis O’Connor Former assistant General Secretary within the NSW Australian Labor Party Elizabeth Waterland Ian Armstrong - Jacqueline Pace - * All lobbyists registered with individual firms do not necessarily work for all of that firm’s clients. Lobby lists are updated regularly. This -

Vic Libs Reeling Over Secret Baillieu Tape PUBLISHED: 24 JUN 2014 12:38:00 | UPDATED: 25 JUN 2014 05:58:53

Vic Libs reeling over secret Baillieu tape PUBLISHED: 24 JUN 2014 12:38:00 | UPDATED: 25 JUN 2014 05:58:53 LUCILLE KEEN AND MATHEW DUNCKLEY An embarrassing leaked recording of former Victorian premier Ted Baillieu criticising other Liberal MPs to journalists has inflamed tensions in the party. In the recording of a conversation with an Age journalist Mr Baillieu slammed the factional divides which led to the selection of Tim Smith to contest the blue-ribbon seat of Kew at the next election. Mr Baillieu supported front bencher Mary Wooldridge in her unsuccessful tilt for the seat. Mr Baillieu also criticises MPs Michael Gidley and Murray Thompson and the conservative faction that overturned Denis Napthine as opposition leader in 2002 to be replaced by Robert Doyle. “The technique with Michael Gidley was the technique with Tim Smith,” Mr Baillieu said. He also criticised balance-of-power MP Geoff Shaw. Mr Shaw quit the parliamentary Liberal Party, citing a lack of faith in the leadership, contributing to Mr Baillieu’s resignation hours later. “Shaw has been sponsored into his position by a bunch of people from the very first day led by Bernie Finn and some crazy mates in the parliamentary team and a very senior member of the organisation who is very close to [federal MP] Kevin Andrews,” he said. Mr Shaw said Mr Baillieu can hold his own opinions but the “sad thing is he didn’t allow” his backbenchers any opinions while he was premier. He said claims about his backers were false and he was in a safe Liberal seat, “he takes for granted”. -

Questions Without Notice Transport Accident Commission

QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE Wednesday, 12 August 1992 ASSEMBLY 59 Wednesday, 12 August 1992 The SPEAKER - Order! The honourable member for Malvern is out of order, as he is well aware. I am quite prepared to take action against him if necessary. The SPEAKER (Hon. Ken Coghill) took the chair at Ms KIRNER - We have determined that there 10.34 a.m. and read the prayer. should be an ongoing dividend that ends up in people's incomes, that reduces business costs and provides community services. We believe this has a QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE greater community benefit than a one-off reduction in premiums. This dividend is equivalent to 20 000 jobs, and when you are making decisions about TRANSPORT ACCIDENT Budgets in recession times, jobs and investment in COMMISSION people have to be the highest priority. The government, the TAC and the Victoria Police Mr KENNElT (Leader of the Opposition) - I refer the Premier to her statement in March this year have worked very hard to ensure that the TAC has when she was responding to the coalition's decision become more viable and has surplus assets because of the decline in the accident rate. That position is to transfer the interest liability for the Pyramid bail-out to the Transport Accident Commission not shared by the opposition which, as the Minister (T AC), which she then described as an inappropriate for Transport said the other day, would extend the licence to kill by raising the speed limit. way of using TAC funds, and ask: given her remarks, how does she now justify the highway robbery that her government intends to impose on Honourable members interjecting. -

In the Public Interest

In the Public Interest 150 years of the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office Peter Yule Copyright Victorian Auditor-General’s Office First published 2002 This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without prior written permission. ISBN 0 7311 5984 5 Front endpaper: Audit Office staff, 1907. Back endpaper: Audit Office staff, 2001. iii Foreword he year 2001 assumed much significance for the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office as Tit marked the 150th anniversary of the appointment in July 1851 of the first Victorian Auditor-General, Charles Hotson Ebden. In commemoration of this major occasion, we decided to commission a history of the 150 years of the Office and appointed Dr Peter Yule, to carry out this task. The product of the work of Peter Yule is a highly informative account of the Office over the 150 year period. Peter has skilfully analysed the personalities and key events that have characterised the functioning of the Office and indeed much of the Victorian public sector over the years. His book will be fascinating reading to anyone interested in the development of public accountability in this State and of the forces of change that have progressively impacted on the powers and responsibilities of Auditors-General. Peter Yule was ably assisted by Geoff Burrows (Associate Professor in Accounting, University of Melbourne) who, together with Graham Hamilton (former Deputy Auditor- General), provided quality external advice during the course of the project. -

On the Couch with Robert Maclellan, 27 January 2015

On the Couch with Robert Maclellan, 27 January 2015 Grant Meyer MPIA CPP Photo: Robert Maclellan, January 2015 Planning News co-editor, Grant Meyer, recently caught up with former Kennett Government Planning Minister, Robert Maclellan, to reflect on his time in office. He speaks candidly on topics including: starting in the job, his relationship with the public service, local government, the planning profession, Docklands, Jeff Kennett, the former Kew asylum site and his legacy. For a man born on the 8th of March 1934, he is still exceptionally sharp and in good physical condition. He confides that he has recently had surgery to remove cataracts from his eyes and has subsequently experienced much improved sight. A review of parliamentary records reveals a 32 year career as a Liberal MP in the Victorian Parliament that included a stint as Leader of the Opposition (1982- 1985), a number of ministry positions, and for the purposes of this article, the Minister for Planning in the Kennett Government between 1992 and 1999. Planning News, 2015 1 Of note, in 2005 he was awarded the Member of the Order of Australia (AM) "for service to the Victorian Parliament, particularly in the areas of planning and transport, and to the community." Now living alone, he describes how his wife, Beverley, passed away in 2008 following a battle with bowel cancer. They had been married for 45 years. He has a good network of family and friends and gets out two evenings per week to play bridge locally. He’s not overly fond of the game but enjoys the social interaction with local men and women. -

Australian Grand Prix Motorsport.Org.Au

2020 MOTORSPORT AUSTRALIA MANUAL TITLES Australian Grand Prix motorsport.org.au Modified Article Date of Application Date of Publication 1. THE AUSTRALIAN GRAND PRIX The title ‘Grand Prix’ has associations extending back to the very earliest days of competition and the French form of the words stems from their first use in association with the French Grand Prix. Although at least one earlier event was given the name “Australian Grand Prix”, the premier Australian race was first recognised in 1928, and has been conducted since then each year except 1936 and during World War II. Since 1949 it has been a scratch race, but in the years 1934, 1935, 1937, 1939, 1947 and 1948, the winner was not the fastest, but won on handicap. Since 1985, the Grand Prix has been a round of the FIA Formula 1™ World Championship. THE LEX DAVISON TROPHY FOR THE AUSTRALIAN GRAND PRIX This trophy, designed and made in Britain by Mr Rex Hays to the order of CAMS, incorporates a silver model of the Austin Seven driven to victory in the first Australian Grand Prix in 1928. The name of the trophy commemorates the late “Lex” Davison, a four-time winner of the Australian Grand Prix (1954, 1957, 1958 and 1961). 2. AUSTRALIAN GRAND PRIX WINNERS Year Venue Winner Vehicle 1928 Phillip Island, Vic ACR Waite (Great Britain) Austin 7 1929 Phillip Island, Vic AJ Terdich Bugatti 1930 Phillip Island, Vic WB Thompson Bugatti 1931 Phillip Island, Vic C Junker Bugatti 1931 Phillip Island, Vic C Junker Bugatti 1931 Phillip Island, Vic C Junker Bugatti 1932 Phillip Island, Vic WB Thompson -

Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings Vol 2

Proceedings of the Second Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two The Windsor Hotel, Melbourne; 30 July - 1 August 1993 Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Foreword (P4) John Stone Foreword Dinner Address (P5) The Hon. Jeff Kennett, MLA; Premier of Victoria The Crown and the States Introductory Remarks (P14) John Stone Introductory Chapter One (P15) Dr Frank Knopfelmacher The Crown in a Culturally Diverse Australia Chapter Two (P18) John Hirst The Republic and our British Heritage Chapter Three (P23) Jack Waterford Australia's Aborigines and Australian Civilization: Cultural Relativism in the 21st Century Chapter Four (P34) The Hon. Bill Hassell Mabo and Federalism: The Prospect of an Indigenous People's Treaty Chapter Five (P47) The Hon. Peter Connolly, CBE, QC Should Courts Determine Social Policy? Chapter Six (P58) S E K Hulme, AM, QC The High Court in Mabo Chapter Seven (P79) Professor Wolfgang Kasper Making Federalism Flourish Chapter Eight (P84) The Rt. Hon. Sir Harry Gibbs, GCMG, AC, KBE The Threat to Federalism Chapter Nine (P88) Dr Colin Howard Australia's Diminishing Sovereignty Chapter Ten (P94) The Hon. Peter Durack, QC What is to be Done? Chapter Eleven (P99) John Paul The 1944 Referendum Appendix I (P113) Contributors Appendix II (P116) The Society's Statement of Purposes Published 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society P O Box 178, East Melbourne Victoria 3002 Printed by: McPherson's Printing Pty Ltd 5 Dunlop Rd, Mulgrave, Vic 3170 National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two ISBN 0 646 15439 7 Foreword John Stone Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society.