1 BBC Features, Radio Voices and the Propaganda of War 1939-1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sense of HUMOUR

Sense of HUMOUR STEPHEN POTTER HENRY HOLT & COMPANY NEW YORK " College Library 14 ... d1SOn ... hurD V,rglt11a l\~rr1Son 0' First published 1954 Reprinted I954 rR q-) I I . I , F>~) AG 4 '55 Set In Bembo 12 poitlt. aHd pritlted at THE STELLAR PRESS LTD UNION STREBT BARNET HBRTS GREAT BRITAIN Contents P ART I THE THEME PAGE The English Reflex 3 Funniness by Theory 6 The Irrelevance of Laughter 8 The Great Originator 12 Humour in Three Dimensions: Shakespeare 16 The Great Age 20 S.B. and G.B.S. 29 Decline 36 Reaction 40 PART II THE THEME ILLUSTRATED Personal Choice 47 1 The Raw Material , , 8 UNCONSCIOUS HUMOUR 4 Frederick Locker-Lampson. At Her Window 52 Ella Wheeler Wilcox. Answered 53 Shakespeare. From Cymbeline 54 TAKING IT SERIOUSLY From The Isthmian Book of Croquet 57 Footnote on Henry IV, Part 2 59 THE PERFECTION OF PERIOD 60 Samuel Pepys. Pepys at the Theatre 61 Samuel Johnson. A Dissertation on the Art of Flying 62 Horace Walpole. The Frustration of Manfred 63 Horace Walpole. Theodore Revealed 64 Haynes Bayly. From She Wore a Wreath of Roses 66 Charles Mackay. Only a Passing Thought 66 E. S. Turner. The Shocking .!fistory of Advertising 67 VB VUl CONTENTS PAGE CHARACTER ON THE SLEEVE 67 Samuel Johnson. On Warburton on Shakespeare 68 James Boswell. On Goldsmith 68 William Blake. Annotations to Sir Joshua Reynolds's Discourses 69 S. T. Coleridge. To his Wife 70 S. T. Coleridge. Advice to a Son 71 S. T. Coleridge. Thanks for a Loan 71 Arnold Bennett and Hugh Walpole. -

The Anglican Concept of Churchmanship

Chapter 1 The Anglican concept of Churchmanship Prologue A distinguished journalist, John Whale, who died in June 2008, was wont to describe Anglicanism as “the most grown up expression of Christianity”. He knew what he was talking about. What led him to that À attering conclusion was undoubtedly his view from the editorial chair of the Church Times. This gave him a unique insight into the extraordinary breadth, height, depth and maturity of Anglican diversity, comprehensiveness and mutual tolerance, unparalleled in any other branch of the Christian Church. That precious, easygoing tolerance, that civilised agreement to differ on so many vital issues, which so impressed Whale (himself born into a contrasting form of ecclesiastical anarchy, his father’s Congregationalism), has worn extremely thin of late, transforming the Church of EnglandSAMPLE and the Anglican Communion worldwide from the appearance of a (more or less) civilised ecclesiastical debating society, into something more like a theatre of war, leading many staunch Anglicans to, or even over, the brink of despair. That, at any rate, is one way of looking at our present situation. It is not, however, the view taken in this book. Its author claims to be as staunch an Anglican as any, though remaining far from uncritical. Born, baptised, con¿ rmed and brought up in the C. of E., serving in its regular ordained parochial ministry for upwards of sixty years and ¿ rmly expecting to end his days in its communion and fellowship, he offers a broader, longer term and in some ways a more hopeful, positive and optimistic perspective, though only too aware of its limitations. -

Frieda Von Richthofen and Karl Von Marbahr

J∙D∙H∙L∙S Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies Citation details Article: ‘The Achievement of the Cambridge Edition of the Letters and Works of D. H. Lawrence: A First Study’ Author: Jonathan Long Source: Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3 (2014) Pages: 129‒151 Copyright: individual author and the D. H. Lawrence Society. Quotations from Lawrence’s works © The Estate of Frieda Lawrence Ravagli. Extracts and poems from various publications by D. H. Lawrence reprinted by permission of Pollinger Limited (www.pollingerltd.com) on behalf of the Estate of Frieda Lawrence Ravagli. A Publication of the D. H. Lawrence Society of Great Britain Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3 (2014) 129 THE ACHIEVEMENT OF THE CAMBRIDGE EDITION OF THE LETTERS AND WORKS OF D. H. LAWRENCE: A FIRST STUDY JONATHAN LONG The title of this essay is an allusion to Stephen Potter’s D. H. Lawrence: A First Study, published in 1930. In fact, as Potter was aware, it was not the first book published on Lawrence. That was Herbert Seligmann’s D. H. Lawrence: An American Interpretation, published in 1924.1 As Potter knew, his study was only the first published in England. Since then hundreds have been published across the world. And there will probably be much more to say about the Cambridge Edition than it is possible to suggest here, reflecting the significance of the Edition and, in turn, the significance of Lawrence, as demonstrated by the number of books published on him. Lawrence’s prolific but relatively short career as a writer of novels, novellas, -

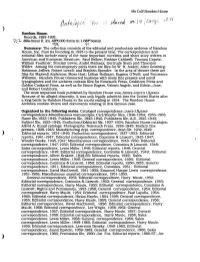

Summary: the Collection Consists of the Editorial and Production Archives of Random House, Inc

Ms CollXRandom House Random House. Records, 1925-1992. £9**linearft. (ca.-Q&F,000 items in 1,657-boxes) 13 % SI Summary: The collection consists of the editorial and production archives of Random House, Inc. from its founding in 1925 to the present time. The correspondence and editorial files include many of the most important novelists and short story writers in American and European literature: Saul Bellow; Erskine Caldwell; Truman Capote; William Faulkner; Sinclair Lewis; Andre Malraux; Gertrude Stein and Thornton Wilder. Among the contemporary poets there are files for W. H. Auden; Allen Ginsberg; Robinson Jeffers; Robert Lowell; and Stephen Spender. In the area of theater there are files for Maxwell Anderson; Moss Hart; Lillian Hellrnan; Eugene O'Neill; and Tennessee Williams. Random House transacted business with many fine presses and noted typographers and the archives contain files for Nonesuch Press, Grabhorn Press and Golden Cockerel Press, as well as for Bruce Rogers, Valenti Angelo, and Edwin, Jane, and Robert Grabhorn. The most important book published by Random House was James Joyce's Ulysses. Because of its alleged obscenity, it was only legally admitted into the United States after a long battle by Random House in the courts ending in 1934. The Random House Archives contain letters and documents relating to this famous case. Organized in the following series: Cataloged correspondence; Joyce-Ulysses correspondence;Miscellaneous manuscripts; Cerf/Klopfer files, 1946-1954; 1956-1965; Name file, 1925-1945; Publishers file, 1925-1945; Publishers file, A-Z, 1925-1945; Subject file, 1925-1945; Production/Editorial file, 1927-1934; Random House cataloges; Alfred A Knopf catalogs; Photographs; Nonesuch Press, 1928-1945; Modem fine presses, 1928-1945; Manufacturing dept. -

Mary Potter on One Page for Booklet 1.3.13

09/12/2013 Mary Potter This year – 2013 - the most famous orchestras, opera companies and conductors in 140 cities across 30 countries are celebrating the centenary of the birth of Benjamin Britten. Beckenham’s links with Britten began in the 1950s and in particular 1957 when he swopped his sea front Crag House for the legendary Red House in Aldeburgh. The other party to the swop was his close friend, the artist Mary Potter, one of the foremost British women artists of her time. Born Mary Attenborough in Beckenham in 1900, she was a colleague and friend of Enid Blyton at St Christopher’s School in Rectory Road before she entered the Beckenham School of Art. From there she used an Orpen Beckenham School of Art bursary award to go the Slade School in October 1918. In 1927 she married Stephen Potter who became famous for his books on gamesmanship which were adapted for the cinema and TV in the 1960’s and 1970’s. They lived in Chiswick and later in Harley Street in London before moving into The Red House in Aldeburgh in 1951. By 1957 after her two sons had grown up and Stephen had left her, Mary found The Red House was too big for her and agreed with a suggestion by her son Julian that she exchange homes with Britten. He was delighted with the exchange but Mary found that Crag House was not as suitable as she had hoped. Aware of this, Britten had built for her a bespoke bungalow and studio in the grounds of The Red House. -

WG and the Savile Club

WG and the Savile Club A Gentlemen's Club is a private (i.e. members-only) establishment typically containing a formal dining room, bar, library, billiards room and one or more rooms for reading, gaming (usually with cards) and socialising. Many clubs also offer guest rooms and fitness amenities. The first such clubs, such as White's (founded in 1693), Boodle's (1762) and Brooks's (1764), were set up and used exclusively by British upper-class men in the West End of London. Today, the area around St James's (a central district in the City of West- minster) is still sometimes called "clubland". The nineteenth century brought an explosion in the popularity of clubs, particularly around the 1880s, when London was home to more than four hundred of them. This expansion can be explained in part by the large extensions of the franchise following the Reform Acts of 1832, 1867 and 1884. In each of those years, many thousands of men were granted voting rights for the first time and it was common for them to feel that, having been elevated to the status of a gentleman, they should belong to a club. The existing clubs, with strict limits on membership numbers and waiting lists of up to sixteen years, were generally wary of such newly enfranchised potential members, prompting some to form clubs of their own. An increasing number of clubs were characterised by their members' shared interest in politics, literature, sport, art, automobiles, travel, geography or some other defining pursuit. In other cases, the connection was service in the same branch of the armed forces, or graduation from the same school or university. -

School Lists Recor the Recordings

DOCUMENT RESUME TE 000 767 ED 022 775 By- Schreiber. Morris, Ed. FOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SECONDARY AN ANNOTATED LIST OFRECORDINGS IN TIC LANGUAGE ARTS SCHOOL COLLEGE National Council of Teachers ofEnglish. Charripaign. IN. Pub Date 64 Note 94p. Available from-National Cound ofTeachers of English. 508 South SixthStreet, Champaign. Illinois 61820 (Stock No. 47906. HC S1.75). EDRS Price MF-S0.50 HC Not Availablefrom MRS. ENGLISH 1)=Ators-Ati:RICAN LITERATURE. AUDIOVISUALAIDS. DRAMA. *ENGLISH INSTRUCTION. TURE FABLES. FICTION. *LANGUAGEARTS. LEGENDS. *LITERATURE.*PHONOGRAPH RECORDS. POETRY. PROSE. SPEECHES The approximately 500 recordings inthis selective annotated list areclassified by sublect matter and educationallevel. A section for elementaryschool lists recor of poetry. folksongs, fairytales. well-known ch4dren's storiesfrom American and w literature, and selections from Americanhistory and social studies.The recordings for both secondary school and collegeinclude American and English prose.poetry. and drama: documentaries: lectures: andspeeches. Availability Information isprovided, and prices (when known) are given.(JS) t . For Elementary School For Secoidary 'School For Colle a a- \ X \ AN ANNOTATED LIST 0 F IN THE LANGUAGE ARTS NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TEACHERSOF tNGLISH U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WILIAM I OFFICE Of EDUCATION TINS DOCUMENT HAS 1EEN REPIODUCED EXACTLY AS DECEIVED FION THE PERSON 01 016ANI1ATION 0116INATNI6 IT.POINTS OF VIEW 01 OPINIONS 1 STATED DO NOT NECESSAINLY REPIESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION 01 POLICY. i AN ANNOTATED LIST OF RECORDINGS IN I THE LANGUAGE ARTS I For 3 Elementhry School Secondary School College 0 o Compiled and Edited bY g MORRIS SCHREIBER D Prepared for the NCI% by the Committee on an Annotated Recording List a Morris Schreiber Chairman Elizabeth O'Daly u Associate Chairman AnitaDore David Ellison o Blanche Schwartz o NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TEACHERS OF ENGLISH u Champaign, Illinois i d NCTE Committee on Publications James R. -

1 BBC Features, Radio Voices and the Propaganda of War 1939-1941

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR BBC Features, Radio Voices and the Propaganda of War 1939-1941 Alex Goody In the early years of the Second World War the BBC Department of Features and Drama became a crucial source for articulating a sense of national unity and for providing accounts of the war to counteract Nazi propaganda. Even before the outbreak of war a Defence Subcommittee advised the BBC that ‘The maintenance of public morale should be the principal aim of wartime programmes’,1 and the early years of the war saw a range of programming designed to boost morale and foster a sense national unity, from early morning prayers (Lift Up Your Hearts) and physical exercises (Up In The Morning Early), to Music While You Work and variety shows (such as Helter-Shelter), to increased educational programming. 2 At the same time the presence of features in the BBC radio schedule expanded. Writers such as Louis MacNeice and Stephen Potter were employed to script and produce features that took on a particular wartime role in broadcasting information and generating a form of official propaganda that could reinforce the shared goals of the Allies.3 If the monologic power of the fascist radio voice underpinned the success of Hitler’s regime in Europe, the features commissioned by the BBC sought to thwart this power with creative expressions of the heterogenic but communal experiences of the British and their allies. However, this essay uncovers the tensions between political and aesthetic conceptions of the radio feature at the beginning of the war.