WG and the Savile Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sense of HUMOUR

Sense of HUMOUR STEPHEN POTTER HENRY HOLT & COMPANY NEW YORK " College Library 14 ... d1SOn ... hurD V,rglt11a l\~rr1Son 0' First published 1954 Reprinted I954 rR q-) I I . I , F>~) AG 4 '55 Set In Bembo 12 poitlt. aHd pritlted at THE STELLAR PRESS LTD UNION STREBT BARNET HBRTS GREAT BRITAIN Contents P ART I THE THEME PAGE The English Reflex 3 Funniness by Theory 6 The Irrelevance of Laughter 8 The Great Originator 12 Humour in Three Dimensions: Shakespeare 16 The Great Age 20 S.B. and G.B.S. 29 Decline 36 Reaction 40 PART II THE THEME ILLUSTRATED Personal Choice 47 1 The Raw Material , , 8 UNCONSCIOUS HUMOUR 4 Frederick Locker-Lampson. At Her Window 52 Ella Wheeler Wilcox. Answered 53 Shakespeare. From Cymbeline 54 TAKING IT SERIOUSLY From The Isthmian Book of Croquet 57 Footnote on Henry IV, Part 2 59 THE PERFECTION OF PERIOD 60 Samuel Pepys. Pepys at the Theatre 61 Samuel Johnson. A Dissertation on the Art of Flying 62 Horace Walpole. The Frustration of Manfred 63 Horace Walpole. Theodore Revealed 64 Haynes Bayly. From She Wore a Wreath of Roses 66 Charles Mackay. Only a Passing Thought 66 E. S. Turner. The Shocking .!fistory of Advertising 67 VB VUl CONTENTS PAGE CHARACTER ON THE SLEEVE 67 Samuel Johnson. On Warburton on Shakespeare 68 James Boswell. On Goldsmith 68 William Blake. Annotations to Sir Joshua Reynolds's Discourses 69 S. T. Coleridge. To his Wife 70 S. T. Coleridge. Advice to a Son 71 S. T. Coleridge. Thanks for a Loan 71 Arnold Bennett and Hugh Walpole. -

'And Plastic Servery Unit Burns

Issue number 103 Spring 2019 PLASTIC SERVERY ’AND BURNS UNIT GIFT SUGGESTIONS FROM The East India Decanter THE SECRETARY’S OFFICE £85 Club directory Ties The East India Club Silk woven tie in club Cut glass tumbler 16 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LH colours. £20 Telephone: 020 7930 1000 Engraved with club Fax: 020 7321 0217 crest. £30 Email: [email protected] Web: www.eastindiaclub.co.uk The East India Club DINING ROOM – A History Breakfast Monday to Friday 6.45am-10am by Charlie Jacoby. Saturday 7.15am-10am An up-to-date look at the Sunday 8am-10am characters who have made Lunch up the East India Club. £10 Monday to Friday 12.30pm-2.30pm Sunday (buffet) 12.30pm-2.30pm (pianist until 4pm) Scarf Bow ties Saturday sandwich menu available £30 Tie your own and, Dinner for emergencies, Monday to Saturday 6.30pm-9.30pm clip on. £20 Sundays (light supper) 6.30pm-8.30pm Table reservations should be made with the Front The Gentlemen’s Desk or the Dining Room and will only be held for Clubs of London Compact 15 minutes after the booked time. New edition of mirror Pre-theatre Anthony Lejeune’s £22 Let the Dining Room know if you would like a quick Hatband classic. £28 V-neck jumper supper. £15 AMERICAN BAR Lambswool in Monday to Friday 11.30am-11pm burgundy, L, XL, Saturday 11.30am-3pm & 5.30pm-11pm XXL. £55 Sunday noon-4pm & 6.30pm-10pm Cufflinks Members resident at the club can obtain drinks from Enamelled cufflinks the hall porter after the bar has closed. -

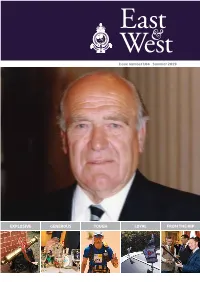

MICKY STEELE-BODGER In

Issue number 104 Summer 2019 EXPLOSIVE GENEROUS TOUGH LOYAL FROM THE HIP GIFT SUGGESTIONS FROM The East India Decanter THE SECRETARY’S OFFICE £85 Club directory Ties The East India Club Silk woven tie in club Cut glass tumbler 16 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LH colours. £20 Telephone: 020 7930 1000 Engraved with club Fax: 020 7321 0217 crest. £30 Email: [email protected] Web: www.eastindiaclub.co.uk The East India Club DINING ROOM – A History Breakfast Monday to Friday 6.45am-10am by Charlie Jacoby. Saturday 7.15am-10am An up-to-date look at the Sunday 8am-10am characters who have made Lunch up the East India Club. £10 Monday to Friday 12.30pm-2.30pm Sunday (buffet) 12.30pm-2.30pm (pianist until 4pm) Scarf Bow ties Saturday sandwich menu available £30 Tie your own and, Dinner for emergencies, Monday to Saturday 6.30pm-9.30pm clip on. £20 Sundays (light supper) 6.30pm-8.30pm The Gentlemen’s Table reservations should be made with the Front Compact mirror Desk or the Dining Room and will only be held for Clubs of London 15 minutes after the booked time. New edition of £22 Pre-theatre Anthony Lejeune’s V-neck jumper Let the Dining Room know if you would like a Hatband classic. £28 Lambswool in navy or quick supper. £15 burgundy, M (navy only), L, AMERICAN BAR XL, XXL. £57 Monday to Friday 11.30am-11pm Saturday 11.30am-3pm & 5.30pm-11pm Sunday noon-4pm & 6.30pm-10pm Cufflinks Members resident at the club can obtain drinks from Enamelled cufflinks the hall porter after the bar has closed. -

Jewel Theatre Audience Guide Addendum: London Gentlemen’S Clubs and the Explorers Club in New York City

Jewel Theatre Audience Guide Addendum: London Gentlemen’s Clubs and the Explorers Club in New York City directed by Art Manke by Susan Myer Silton, Dramaturg © 2019 GENTLEMEN’S CLUBS IN LONDON Nell Benjamin describes her fictional Explorers Club in the opening stage directions of the play: We are in the bar of the Explorers club. It is decorated in high Victorian style, with dark woods, leather chairs, and weird souvenirs from various expeditions like snowshoes, African masks, and hideous bits of taxidermy. There is a sofa, a bar, and several cushy club chairs. A stair leads up to club bedrooms. Pictured above is the bar at the Savile Club in London, which is a traditional gentlemen’s club founded in 1868 and located at 69 Brook Street in Mayfair. Most of the gentlemen’s clubs in existence in London in 1879, the time of the play, had been established earlier, and were clustered together closer to the heart of the city. Clubs in the Pall Mall area were: The Athenaeum, est. 1824; The Travellers Club, est. 1819; The (original) Reform Club, 1832; The Army and Navy Club, 1837; Guard’s Club, 1810; United University Club, est. 1821, which became the Oxford and Cambridge Club in 1830; and the Reform Club (second location), est. 1836. Clubs on St. James Street were: Whites, est. 1693; Brooks, est. 1762; Boodles, est. 1762; The Carlton Club, 1832; Pratt’s, est. 1857; and Arthur’s, est. 1827. Clubs in St. James Square were: The East India Club, est. 1849 and Pratt’s, est. 1857. -

East-And-West-Magazine-Summer-2018.Pdf

Issue number 101 Summer 2018 FLYERS PEAK PERFORMANCE OVER A SENTRY GIFT SUGGESTIONS FROM Sport was a rollercoaster throughout autumn, winter and The East India Decanter Club diary THE SECRETARY’S OFFICE £85 spring. Showing a more reliable pattern, club events included Club directory Ties Christmas festivities, popular dinners with a Scottish and CHAIRMAN’S REPORT The East India Club Silk woven tie in club April 2018 Cut glass tumbler English theme, and a general feeling of oasis in St James’s. 16 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LH colours. £20 18 Young members’ dinner Engraved with club Telephone: 020 7930 1000 25 Wellington Barracks visit crest. £30 Fax: 020 7321 0217 26 St George’s day dinner Email: [email protected] CHAIRMAN’S REPORT Web: www.eastindiaclub.co.uk The East India Club DINING ROOM – A History May Breakfast by Charlie Jacoby. 7 Bank holiday 017 concluded with a busy club excellent evening with businesswoman and Monday to Friday 6.45am-10am An up-to-date look at the 9 AGM programme, on consecutive nights in television personality Dr Margaret Mountford Saturday 7.15am-10am characters who have made Sunday 8am-10am 18 Evening of jazz December, including the tri clubs party providing sound career advice for the next Scarf up the East India Club. £10 2 21 Wine Tour of Bordeaux and carol concert, featuring the impressive generation as well as recalling the lighter Lunch £17 Monday to Friday 12.30pm-2.30pm 28 Bank holiday Gentlemen of Hampton Court. These events moments of working with Lord Sugar on The Sunday (buffet) 12.30pm-2.30pm were well supported and a good number of Apprentice. -

Who Founded the East India Club?

Who founded the East India Club? There has long been an assumption that the East India Company founded the club. This is probably not correct. The exact origins of the East India Club are indistinct. Several versions of our founding exist. A report in The Times of 6 July 1841 refers to the East India Club Rooms at 26 Suffolk Street, off Pall Mall East. It says that the rooms are open for the accommodation of the civil and military officers, of Her Majesty’s and the Hon. East India Company’s service, members of Parliament, and private and professional gentlemen. The clubrooms seem to have been in use for some time because the report also exhorts Major D D Anderson, Madam Fitzgerald, Captain Alfred Lewis, Mr M Farquhar from Canada, Lieutenant Edward Stewart, and another Stewart Esquire to come and pick up their unclaimed letters. This is supported by Sir Arthur Happel, Indian Civil Service (1891 to 1975) who says that the club grew out of a hostel for East India Company servants maintained in London to help them with leave problems. The records of the East India United Services Club date from 1851. An article of July 1853 cited in Foursome in St James’s states that the club as we know it was born at a meeting held at the British Hotel in Cockspur Street in February 1849. The consequence was the acquisition of No 16 St James’s Square as the clubhouse, and the holding of an inaugural dinner there on 1 January 1850. Edward Boehm – who owned the house in 1815 when Major Percy presented the French Eagles to the Prince Regent after the Battle of Waterloo on 21 June – went bankrupt, and a Robert Vyner bought it from him. -

Agenda Paris 2018

7th May 2018 (v.1) EUROPEAN INTER-CLUB WEEKEND general information ORGANIZATION Gold Alliance in collaboration with and as a joint venture among: Automobile Club de France Cercle de l’Union Interalliée ST. JOHANNS CLUB | Vienna, Austria THE NAVAL CLUB | London, Great Britain ROYAL INTERNATIONAL CLUB CHÂTEAU SAINTE-ANNE | Brussels, Belgium THE TRAVELLERS CLUB | London, Great Britain CERCLE ROYAL GAULOIS | Brussels, Belgium CITY UNIVERSITY CLUB | London, Great Britain CERCLE ROYAL LA CONCORDE | Brussels, Belgium OXFORD AND CAMBRIDGE CLUB | London, Great Britain DE WARANDE | Brussels, Belgium THE REFORM CLUB | London, Great Britain DE KAMERS | Antwerpen, Belgium THE CAVALRY AND GUARDS CLUB | London, Great Britain CERCLE DE LORRAINE | Brussels, Belgium THE EAST INDIA CLUB | London, Great Britain SOCIÉTÉ LITTÉRAIRE | Brussels, Belgium BROOKS'S | London, Great Britain CERCLE ROYAL DU PARC | Brussels, Belgium THE ARTS CLUB | London, Great Britain CÍRCULO ECUESTRE | Barcelona, Spain NATIONAL LIBERAL CLUB | London, Great Britain CÍRCULO LICEO | Barcelona, Spain THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB | London, Great Britain SOCIEDAD BILBAINA | Bilbao, Spain THE HURLIGHAM CLUB | London, Great Britain REAL GRAN PEÑA | Madrid, Spain ROYAL LONDON YACHT CLUB | London, Great Britain NUEVO CLUB | Madrid, Spain THE ULSTER REFORM CLUB | London, Great Britain CASINO DE AGRICULTURA VALENCIA | Valencia, Spain CERCLE MUNSTER | Luxembourg, Luxembourg REAL CLUB ANDALUCÍA (AERO) | Sevilla, Spain STEPHENS GREEN HIBERNIAN CLUB | Dublin, Ireland CLUB FINANCIERO GÉNOVA | Madrid, -

Summer Cricket in the Library Blind

Issue number 88 April 2014 SUMMER CRICKET BLIND TASTING IN THE LIBRARY HAGGIS NIGHTS KING OF OUDH GIFT SUGGESTIONS From TUMBLERS The East India Square tumbler THE secretary’S OFFICE Engraved with club Club directory crest. £18.50 ATTIRE The East India Club Club ties Decanter 16 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LH Silk woven tie in club £75 Telephone: 020 7930 1000 colours. £19.50 Fax: 020 7321 0217 Email: [email protected] Web: www.eastindiaclub.co.uk Cut glass tumbler DINING ROOM Breakfast Engraved with club Monday to Friday 6.45am-10am crest. £25.75 Saturday 7.15am-10am Sunday 8am-10am Lunch BOOKS & CDs The East India Club Monday to Friday 12.30pm-2.30pm Club bow ties Sunday (buffet) 12.30pm-2.30pm – A History Tie your own and, (pianist until 4pm) by Charlie Jacoby. for emergencies, An up-to-date look at Saturday sandwich menu available clip on. £19.50 the characters who have Dinner Scarf made up the East India Monday to Saturday 6.30pm-9.30pm Club. £10 Sundays (light supper) 6.30pm-8.30pm £17 Club song Table reservations should be made with the Front Awake! Awake! Desk or the Dining Room and will only be held for A recording of the club 15 minutes after the booked time. Cufflinks song from the 2009 St Enamelled cufflinks AMERICAN BAR George’s Day dinner. £5 Monday to Friday 11.30am-11pm with club crest, Saturday 11.30am-3pm chain or bar. £24.50 The Gentlemen’s & 5.30pm-11pm Sunday noon-4pm Clubs of London & 6.30pm-10pm New edition of Drinks can be obtained in the Waterloo Room from Anthony Lejeune’s Monday to Sunday. -

Open Government: Lessons from America

OPEN GOVERNMENT Lessons from America STEWART DRESNER May 1980 £3.00 OPEN GOVERNMENT: LESSONS FROM AMERICA CONTENTS Page Foreword Preface I Introduction 1 II The Open Government Concept and the British Government response 3 III Hew Open Government Legislation works in the United States 8 (1) Hie Freedom of Information Act 8 (2) The Privacy Act 25 (3) The Government in the Sunshine Act 31 IV What needs to be kept secret? 42 V Who uses the American Open Government Laws? 60 (1) Public Interest Groups 61 (2) The Media 69 (3) Individuals and Scholars 74 (4) Companies 76 (5) Civil Servants 80 VI Balancing Public Access to Government Information with the Protection of Individual Privacy 88 (1) The Issues 88 (2) The Protection of Personal Information by the U.S. Privacy Act 1974 91 (3) The Personal Privacy Exenption to the 101A 96 (4) The Relationship between the IOIA and the PA 98 (5) Public Access and Privacy Protection in an Administrative Programme 99 ii Page VII Ensuring Government Compliance with Public Access legislation 105 (1) Actaiinistrative Procedures 105 (2) Appeal Procedures 107 (3) Monitoring the Effectiveness of Public Access Legislation 117 VIII Ihe Costs and Benefits of Open Government 126 (1) National Security 127 (2) Constitutional Relationships 127 (3) Administrative and other Costs 132 IX Conclusion: Information, Democracy and Power 141 Bibliography i-xi FOREWORD Last year the related subjects of official secrets and freedom of information had a thorough but abortive airing. Mr. Clement Freud's Official Information Bill after a long and interesting committee stage became a victim of the general election. -

Financial Times , 1986, UK, English

. » . , ' ftmfi 1 .'. ,-'SdL?0 Wma.. 10 2563 .. hisa • B**--fr-0&50 ** Capital markets: um S Af a^a . Re : 9**» S CO *»...., ,Y550 GSUH> S*g*Rf . SS< \0 M.„ • -.ffcWO CULTS ... P»1H w*w - • pfife %B7 W releasing 3" ****'. .DwU.Ob.LM '.Ik: 33 Ki.» S«A . Or?H -fetal V..M&3) $***=6 SfcTTj the bonds. Page 17 Aw* -- ffi. 8.00 "K*'S95 9*pf. W2.» l«=s» FINANCIALTIME .rftaftC'3 ; N r*fer *_ l?33 EUROPE’S gj-2Ssag tag. ns £^3*" J/ BUSINESS NEWSPAPER > £- ..sGk&W ....ft*. 15 fe4l 34*- rSUSi O j .y- No. 29,923 Thursday May 8 1986 D 8523 B Workf news summary.. --I Summit accord ®“t'h e*S *OllC0 »tab„ a^io, S?V CO-OPf^ £ • i •u * jl will not inhibit explosion Bank team With llUClear body crack dowa on share blamed goes to US retaliation’ BY REGINALD DALE IN TOKYO salesmen 2tito on Tamils Grenfell over Chernobyl PRESIDENT Ronald Reagan yes- however, be shared by European By Clive Wolman In London mocked A-bomb two floors of Col- MORGAN terday made clear that he did not leaders, who had thought that their central GRENFELL has recruit . on*6’s telegraph office, kill. regard the Tokyo summit agree- willingness to subscribe to new DUTCH police have mounted a seri- ed a six-member team from New BY PATRICK BLUM IN VIENNA po- people ment to combat terrorism by politi- es of searcb-and'Seijure raids on mg 31 and wounding 114. York's litical measures would head off fur- Chemical Bank to head its Sri Union is being took placeln the early hours of the use of nuclear energy. -

Convivial Companionship

CONVIVIAL COMPANIONSHIP The Savile Club, London by Lew Toulmin We stayed at the Savile Club in Mayfair for two nights in August 2017. The club is housed in a large double townhouse in Mayfair, near Claridge’s Hotel, at 69 Brook Street. This is a traditional men’s club, with a distinguished membership drawing on the arts, writing, music and other professions. HISTORY The Savile Club began life in 1868 as the New Club, but changed its name to the Savile Club when it moved to Savile Row in Mayfair in 1871. Moving again to an excellent site overlooking Green Park, the club was forced to move yet again in 1927 when it’s building virtually collapsed due to construction works next door. The final and current site, at 69 and 71 Brooke Street, about three blocks east of the soon- to-be-moved US Embassy, was purchased from the daughter of “Lou-lou” Lewis Harcourt, 1st Viscount Harcourt. He was a Liberal Secretary of State for the Colonies who had committed suicide when his paedophilia was about to be publicly exposed. The house had been lavishly redecorated and renovated in two waves between 1892 and 1920 by the owners, who were linked to the famous Morgan banking family of the USA. MEMBERSHIP Full membership in the Club is still restricted to men, but there are no parts of the club that are closed to women, and female reciprocal members may stay, come and go freely. Membership reflects the various geographical moves the club has made, especially the recent location near broadcasting and publishing firms. -

Just a Classic Minute: V. 6 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

JUST A CLASSIC MINUTE: V. 6 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ian Messiter,Nicholas Parsons,Paul Merton | 1 pages | 02 Jul 2009 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9781405688116 | English | London, United Kingdom Just a Classic Minute: v. 6 PDF Book Notify me of new comments via email. BBC News. Cancel anytime. Audible Premium Plus. At the time my mother said to me, 'Apparently Dad was a national treasure Remove from wishlist failed. All rights reserved. These quick bread recipes are bursting with fall flavors! Nicholas Parsons chaired the show, and Tony Slattery featured in all programmes. Nicholas Parsons chaired the show from its inception until his death in January Until he also sat on the stage with a stopwatch and blew a whistle when the sixty seconds were up. Nicholas Parsons gives commentary between episodes relating backstory and history of the people involved. Chocolate cupcakes can be transformed by spices added to the batter, sneaking a surprise in the center, or the creamy frosting piped on top. Web icon An illustration of a computer application window Wayback Machine Texts icon An illustration of an open book. Add Ingredients to Grocery List. My Recipe Box. No Reviews are Available. Please refresh the page and retry. Several television versions have been attempted. It is rare for a panellist to speak within the three cardinal rules for any substantial length of time, whilst both remaining coherent and being amusing. It also was one of the first animated shows to get A-list guest stars, from the likes of Tony Curtis playing a character called Stony Curtis and Ann-Margret playing a character named, you guessed it, Ann-Margrock.