6 2-Global-Power-Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

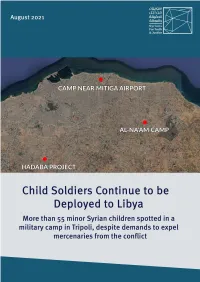

Child Soldiers Continue to Be Deployed to Libya

www.stj-sy.org Child Soldiers Continue to be Deployed to Libya More than 55 minor Syrian children spotted in a military camp in Tripoli, despite demands to expel mercenaries from the conflict Page | 2 www.stj-sy.org Despite an October 2020 ceasefire agreement and repeated international calls to expel all foreign forces and mercenaries from the Libyan conflict, recruitment operations continue to enlist and transfer Syrian mercenaries into Libya – including children under the age of 18. In 2021, the recruitments have largely been carried out by Russia and Turkey. In July 2021, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) obtained new testimonies on the deployment of new groups of children to Tripoli, Libya’s capital, since March 2021. Notably, we heard from a 16-year-old child soldier, a fighter in the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division, and a medical worker who treated a number of recruited children in a hospital in Tripoli. We contacted sources via phone and through encrypted online applications. Sources confirmed the spread of 55 new Syrian child recruits in areas overseen by the Government of National Accord (GNA), including makeshift camp near Mitiga International Airport, al-Sahbah camp, Hadaba project and al-Na’am camp. Image 1 – A map of locations where Syrian child soldiers have been observed in Libya. Military Groups Recruiting Children Sources provided STJ with the names of military groups formed by the opposition-Syrian National Army (SNA) who are confirmed to have children serving among their ranks in Libya. The groups include the Auxiliary Forces/al-Quwat al-Radifa, Front and Alert Units, and Special Intrusion Units. -

Syrian Armed Opposition Powerbrokers

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda. -

Reimagining US Strategy in the Middle East

REIMAGININGR I A I I G U.S.S STRATEGYT A E Y IIN THET E MMIDDLED L EEASTS Sustainable Partnerships, Strategic Investments Dalia Dassa Kaye, Linda Robinson, Jeffrey Martini, Nathan Vest, Ashley L. Rhoades C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA958-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0662-0 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover composite design: Jessica Arana Image: wael alreweie / Getty Images Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface U.S. -

WEEKLY REPORT 21 – 28 May 2021

WEEKLY REPORT 21 – 28 May 2021 KEY DYNAMICS Presidential elections .................................................................................................... 2 Assad elected for 4th term .......................................................................... 2 IDPs stranded ................................................................................................................. 3 Um Batna families deported ....................................................................... 3 Self-Administration, ISIS concerns ............................................................................ 4 ISIS continue to attack .................................................................................. 4 MERCY CORPS HUMANITARIAN ACCESS WEEKLY REPORT, 21 – 28 May 2021 1 Presidential elections Voter turnout low, contrary to government media reports Assad elected for 4th term Despite pro-government media claiming that Bashar al-Assad has been re-elected president of voter turnout was high, reports from local Syria in a landslide victory, in which he officially sources directly contradict this. Election centers received 95.1% of the votes. The result, although in Syrian government areas were largely empty ultimately unsurprising due to both the lack of save for a few where pro-government citizens viable opposition candidates and expected and Baath party members gathered in front of fraudulency of the elections themselves, did not cameras to welcome government officials going come without disruptions. to vote. Voters were for -

The Turkey-UAE Race to the Bottom in Libya: a Prelude to Escalation

The Turkey-UAE race to the bottom in Libya: a prelude to escalation Recherches & Documents N°8/2020 Aude Thomas Research fellow, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique July 2020 www.frstrategie.org SOMMAIRE THE TURKEY-UAE RACE TO THE BOTTOM IN LIBYA: A PRELUDE TO ESCALATION ................................. 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 1. TURKEY: EXERCISING THE FULL MILITARY CAPABILITIES SPECTRUM IN LIBYA ............................. 3 2. THE UAE’S MILITARY VENTURE IN LIBYA ................................................................................ 11 2.1. The UAE’s failed campaign against Tripoli ....................................................... 11 2.2. Russia’s support to LNA forces: from the shadow to the limelight ................ 15 CONCLUSION: LOOKING AT FUTURE NATIONAL DYNAMICS IN LIBYA ................................................... 16 FONDATION pour la RECHERCHE STRATÉ GIQUE The Turkey-UAE race to the bottom in Libya: a prelude to escalation This paper was completed on July 15, 2020 Introduction In March, the health authorities in western Libya announced the first official case of Covid- 19 in the country. While the world was enforcing a lockdown to prevent the spread of the virus, war-torn Libya renewed with heavy fighting in the capital. Despite the UNSMIL’s1 call for a lull in the fighting, the Libyan National Army (LNA) and its allies conducted shelling on Tripoli, targeting indistinctly residential neighbourhoods, hospitals and armed groups’ locations. The Government of National Accord (GNA) answered LNA’s shelling campaign by launching an offensive against several western cities. These operations could not have been executed without the support of both conflicting parties’ main backers: Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The protracted conflict results from both the competing parties’ unwillingness to agree on conditions to resume political negotiations2. -

Operation Euphrates Shield: Implementation and Lessons Learned Lessons and Implementation Shield: Euphrates Operation

REPORT REPORT OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD: IMPLEMENTATION OPERATION AND LESSONS LEARNED EUPHRATES MURAT YEŞILTAŞ, MERVE SEREN, NECDET ÖZÇELIK The report presents a one-year assessment of the Operation Eu- SHIELD phrates Shield (OES) launched on August 24, 2016 and concluded on March 31, 2017 and examines Turkey’s future road map against the backdrop of the developments in Syria. IMPLEMENTATION AND In the first section, the report analyzes the security environment that paved the way for OES. In the second section, it scrutinizes the mili- tary and tactical dimensions and the course of the operation, while LESSONS LEARNED in the third section, it concentrates on Turkey’s efforts to establish stability in the territories cleansed of DAESH during and after OES. In the fourth section, the report investigates military and political MURAT YEŞILTAŞ, MERVE SEREN, NECDET ÖZÇELIK lessons that can be learned from OES, while in the fifth section, it draws attention to challenges to Turkey’s strategic preferences and alternatives - particularly in the north of Syria - by concentrating on the course of events after OES. OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD: IMPLEMENTATION AND LESSONS LEARNED LESSONS AND IMPLEMENTATION SHIELD: EUPHRATES OPERATION ANKARA • ISTANBUL • WASHINGTON D.C. • KAHIRE OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD IMPLEMENTATION AND LESSONS LEARNED COPYRIGHT © 2017 by SETA All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, without permission in writing from the publishers. SETA Publications 97 ISBN: 978-975-2459-39-7 Layout: Erkan Söğüt Print: Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık A.Ş., İstanbul SETA | FOUNDATION FOR POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RESEARCH Nenehatun Caddesi No: 66 GOP Çankaya 06700 Ankara TURKEY Tel: +90 312.551 21 00 | Fax :+90 312.551 21 90 www.setav.org | [email protected] | @setavakfi SETA | İstanbul Defterdar Mh. -

UK Home Office

Country Policy and Information Note Syria: the Syrian Civil War Version 4.0 August 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

Turkish Invasions

Turkey’s Invasion Campaigns in Syria Washington Kurdish Institute September 8, 2020 The report highlights the activities of ISIS since the Turkish invasion of the Kurdish region and Turkey’s three invasion campaigns in Syria since 2016. 1 www.dckurd.org Islamic State Sleeper-Cell Activities from October 2019 - July 2020 Since the beginning of the Turkish invasion into the Kurdish region of Syria, the so-called “Operation Peace Spring” of October 2019, the activity of ISIS sleeper- cells has changed significantly over the course of late 2019 and the first 7 months of 2020. There was a noticeable increase in attacks that correlated with the Turkish invasion, likely as a result of the Kurdish -led and US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) needing to reroute manpower and equipment towards the frontlines near where Turkey occupied in Gire Spi (Tal Abyad) and Serekaniye (Ras al-Ain). Following the end of offensive operations by the Turkish-backed forces, the activities of sleeper-cells dipped significantly, including arson attacks on the farmlands under the control of the SDF. However, in June, activity significantly decreased again, directly correlating with the beginning of the “Deterrence of Terror” operation that the SDF began conducting with Coalition forces. This led to a major increase in raids, which directly seemed to impact the activity and number of attacks. Notably in some cases, despite the number of attacks decreasing, the efficiency in terms of casualties (especially assassinations of political and tribal figures) seemed to increase. Overall, what can be concluded is that Deir Ez Zor province will continue to be a hotbed of instability for the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration of North and East of Syria (AANES), due mostly to ISIS activity, but also partially because of the Syrian regime influence, and increasingly, sleeper-cell activities of the Turkish-backed groups. -

The Best of Bad Options for Syria's Idlib

The Best of Bad Options for Syria’s Idlib Middle East Report N°197 | 14 March 2019 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Idlib’s De-escalation and the Sochi Memorandum .......................................................... 3 III. Idlib’s Rebel Scene ............................................................................................................ 6 A. Hei’at Tahrir al-Sham ................................................................................................ 7 1. HTS’s administrative and economic project ........................................................ 9 2. HTS’s ambiguous identity .................................................................................... 13 B. Other Jihadists ........................................................................................................... 17 1. Hurras al-Din/Wa-Harridh al-Mu’mineen operations room .............................. 17 2. Turkistan Islamic Party in Syria ........................................................................... 19 3. Miscellaneous jihadists ....................................................................................... -

General Assembly Security Council Seventy-Fifth Session Seventy-Fifth Year Agenda Items 34, 71, 114 and 135

United Nations A/75/644–S/2020/1191 General Assembly Distr.: General 14 December 2020 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Seventy-fifth session Seventy-fifth year Agenda items 34, 71, 114 and 135 Prevention of armed conflict Right of peoples to self-determination Measures to eliminate international terrorism The responsibility to protect and the prevention of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity Letter dated 10 December 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Armenia to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General Further to my letters dated 3 October (A/75/491-S/2020/976), 5 October (A/75/496-S/2020/984) and 31 October (A/75/566-S/2020/1073), I am enclosing herewith the Report on the involvement of foreign terrorist fighters and mercenaries by Azerbaijan in the aggression against Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) (see annex). I kindly request that the present letter and its annex be circulated as a document of the General Assembly, under agenda items 34, 71, 114 and 135 and of the Security Council. (Signed) Mher Margaryan Ambassador Permanent Representative 20-17210 (E) 221220 *2017210* A/75/644 S/2020/1191 Annex to the letter dated 10 December 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Armenia to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General REPORT ON THE USE OF FOREIGN TERRORIST FIGHTERS (FTFs) BY AZERBAIJAN IN THE AGGRESSION TO SUPPRESS THE INALIENABLE RIGHT OF THE PEOPLE OF ARTSAKH (NAGORNO-KARABAKH) TO SELF-DETERMINATION (as of October 31, 2020) 2/41 20-17210 A/75/644 S/2020/1191 Contents Chapter 1: Overview ........................................................................................................................................ -

Middle East Security Report 29

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda. -

Terrorism in Afghanistan: a Joint Threat Assessment

Terrorism in Afghanistan: A Joint Threat Assessment Terrorism in Afghanistan: A Joint Threat Assessment Introduction 7 Chapter I: Afghanistan’s Security Situation and Peace Process: Comparing U.S. and Russian Perspectives (Barnett R. Rubin) 9 Chapter II: Militant Terrorist Groups in, and Connected to, Afghanistan (Ekaterina Stepanova and Javid Ahmad) 24 Chapter III: Afghanistan in the Regional Security Interplay Context (Andrey Kazantsev and Thomas F. Lynch III) 41 Major Findings and Conclusions 67 Appendix A: Protecting Afghanistan’s Borders: U.S. and Russia to Lead in a Regional Counterterrorism Effort (George Gavrilis) 72 Appendix B: Arms Supplies for Afghan Militants and Terrorists (Vadim Kozyulin) 75 Appendix C: Terrorism Financing: Understanding Afghanistan’s Specifics (Konstantin Sorokin and Vladimir Ivanov) 79 Acronyms 83 Terrorism in Afghanistan Joint U.S.-Russia Working Group on Counterterrorism in Afghanistan Working Group Experts: Javid Ahmad1 Senior Fellow, Atlantic Council Sher Jan Ahmadzai Director, Center for Afghanistan Studies, University of Nebraska at Omaha Robert Finn Former Ambassador of the United States to Afghanistan George Gavrilis Fellow, Center for Democracy, Toleration, and Religion, University of California, Berkeley Andrey Kazantsev Director, Center for Central Asian and Afghan Studies, Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO University) Kirill Koktysh Associate Professor, Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO University) Member, Expert Council, State Duma Committee of Nationalities Mikhail Konarovsky Former Ambassador of the Russian Federation to Afghanistan Col. (Ret.) Oleg V. Kulakov* Professor of Area Studies, Military University, Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation Vadim Kozyulin Member, PIR Center Executive Board Researcher, Diplomatic Academy, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation Thomas F.