Maurice Ravel and Paul Wittgenstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALEXANDRE THARAUD Les Artistesharmoniamundienconcert Fourviere.Org

information presse ARLES PARIS LOS ANGELES LONDON HEIDELBERG BARCELONA DEN HAAG BRUXELLES harmonia mundi s.a. les artistes harmonia mundi en concert service promotion 33, rue Vandrezanne 75013 Paris jean-marc berns / matthieu benoit Tél. 01 53 80 02 22 Fax 01 53 80 02 25 [email protected] ALEXANDRE THARAUD, piano n° 2431 BARTABAS, conception et mise en scène ACADÉMIE DU SPECTACLE ÉQUESTRE DE VERSAILLES « RÉCITAL ÉQUESTRE » JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Concertos italiens 14, 15, 16 & 17 juin 2006, 22 h LES NUITS DE FOURVIÈRE THÉÂTRE ROMAIN DE FOURVIÈRE— Lyon, 5e http://www.nuits-de-fourviere.org/ récemment paru FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN 19 Valses FEDERICO MOMPOU Valse-Évocation (Variations sur un thème de Chopin) Alexandre Tharaud, piano HMC 901927 www.harmoniamundi.com www.harmoniamundi.com information presse ARLES PARIS LOS ANGELES LONDON HEIDELBERG BARCELONA DEN HAAG BRUXELLES alexandre tharaud ’est pour harmonia mundi qu’Alexandre Tharaud a enregistré au piano son disque dédié aux Suites de clavecin de Rameau, une des révélations discographiques de 2001. Suite à ce C succès international, Alexandre Tharaud a été invité à se produire en récital aux célèbres BBC PROMS, au Festival de Piano de la Roque d’Anthéron, dans la série ‘MeisterZyklus’ de Bern, au Festival de Musique Ancienne d’Utrecht, à Saintes, à l’Abbaye de l’Épau et au Festival de Radio France et de Montpellier. Il a également donné des récitals au Concertgebouw d’Amsterdam, au Théâtre du Châtelet, au Musée d’Orsay et à la Cité de la Musique à Paris, ainsi qu’au Teatro Colón de Buenos Aires. Ses débuts aux États-Unis en mars 2005 ont été salués par la critique (New York Times, Washington Post). -

Jean-Guihen Queyras Violoncello

JEAN-GUIHEN QUEYRAS VIOLONCELLO Biography Curiosity, diversity and a firm focus on the music itself characterize the artistic work of Jean- Guihen Queyras. Whether on stage or on record, one experiences an artist dedicated completely and passionately to the music, whose humble and quite unpretentious treatment of the score reflects its clear, undistorted essence. The inner motivations of composer, performer and audience must all be in tune with one another in order to bring about an outstanding concert experience: Jean-Guihen Queyras learnt this interpretative approach from Pierre Boulez, with whom he established a long artistic partnership. This philosophy, alongside a flawless technique and a clear, engaging tone, also shapes Jean-Guihen Queyras’ approach to every performance and his absolute commitment to the music itself. His approaches to early music – as in his collaborations with the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra and the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin – and to contemporary music are equally thorough. He has given world premieres of works by, among others, Ivan Fedele, Gilbert Amy, Bruno Mantovani, Michael Jarrell, Johannes-Maria Staud, Thomas Larcher and Tristan Murail. Conducted by the composer, he recorded Peter Eötvös’ Cello Concerto to mark his 70th birthday in November 2014. Jean-Guihen Queyras was a founding member of the Arcanto Quartet and forms a celebrated trio with Isabelle Faust and Alexander Melnikov; the latter is, alongside Alexandre Tharaud, a regular accompanist. He has also collaborated with zarb specialists Bijan and Keyvan Chemirani on a Mediterranean programme. The versatility in his music-making has led to many concert halls, festivals and orchestras inviting Jean-Guihen to be Artist in Residence, including the Concertgebouw Amsterdam and the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, Vredenburg Utrecht, De Bijloke Ghent and the Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg. -

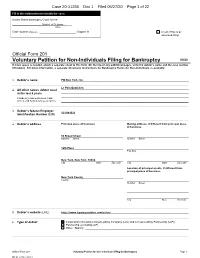

Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy 04/20 If More Space Is Needed, Attach a Separate Sheet to This Form

Case 20-11266 Doc 1 Filed 05/27/20 Page 1 of 22 Fill in this information to identify the case: United States Bankruptcy Court for the: ____________________ District of Delaware (State) Case number (If known): _________________________ Chapter 11 Check if this is an amended filing Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy 04/20 If more space is needed, attach a separate sheet to this form. On the top of any additional pages, write the debtor’s name and the case number (if known). For more information, a separate document, Instructions for Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, is available 1. Debtor’s name PQ New York, Inc. Le Pain Quotidien 2. All other names debtor used in the last 8 years Include any assumed names, trade names, and doing business as names 3. Debtor’s federal Employer 13-3841022 Identification Number (EIN) 4. Debtor’s address Principal place of business Mailing address, if different from principal place of business 50 Broad Street Number Street Number Street 12th Floor P.O. Box New York, New York 10004 City State Zip Code City State Zip Code Location of principal assets, if different from principal place of business New York County County Number Street City State Zip Code 5. Debtor’s website (URL) https://www.lepainquotidien.com/us/en/ 6. Type of debtor Corporation (including Limited Liability Company (LLC) and Limited Liability Partnership (LLP)) Partnership (excluding LLP) Other. Specify: Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy Page 1 RLF1 22931188v.9 Debtor PQ New York, Inc. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

Georges Enesco Au Conservatoire De Paris (1895 – 1899)

GEORGES ENESCO AU CONSERVATOIRE DE PARIS (1895 – 1899) JULIEN SZULMAN VIOLON PIERRE-YVES HODIQUE PIANO GEORGES ENESCO AU CONSERVATOIRE DE PARIS (1895 – 1899) GEORGES ENESCO ANDRÉ GÉDALGE GEORGES ENESCO MARTIN-PIERRE MARSICK Sonate n°1 pour piano et violon Sonate n°1 pour piano et violon Sonate n°2 pour piano et violon 11. Attente - Poème d’été opus 2 opus 12 opus 6 pour violon et piano 1. Allegro vivo — 7’42 4. Allegro moderato 8. Assez mouvementé — 8’40 opus 24 n°3 — 3’56 — 2’18 2. Quasi adagio — 9’28 e tranquillamente 9. Tranquillement — 7’12 3. Allegro — 8’00 5. Vivace — 3’35 10. Vif — 7’49 6. Adagio non troppo — 3’34 7. Presto con brio — 3’34 durée totale — 75’51 JULIEN SZULMAN — VIOLON PIERRE-YVES HODIQUE — PIANO RETOUR AUX SOURCES Élève d’un élève du violoniste Christian Halphen, dédiée à Enesco, composée final est indiqué « trompette », représentant Nationale de France. À de rares exceptions Ferras, j’ai très tôt été fasciné par la figure de seulement à partir de juillet 1899, et donc « un gosse de Poulbot ». L’écoute des près, les nombreux doigtés indiqués par son mentor Georges Enesco. Compositeur, postérieure aux études du violoniste au deux enregistrements du compositeur Marsick ont été respectés. violoniste, pianiste, chef d’orchestre : Conservatoire. Ce programme permet de (avec Chailley-Richez, et en 1943 avec la multiplicité de ses talents en fait une découvrir la personnalité marquante du Dinu Lipatti) est riche d’enseignements sur Ces différentes sources me sont d’une figure incontournable de l’histoire de la jeune Georges Enesco, et l’environnement la liberté du jeu des musiciens et du choix aide précieuse pour m’approcher au plus musique de la première moitié du XXe siècle. -

A Study of Ravel's Le Tombeau De Couperin

SYNTHESIS OF TRADITION AND INNOVATION: A STUDY OF RAVEL’S LE TOMBEAU DE COUPERIN BY CHIH-YI CHEN Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University MAY, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music ______________________________________________ Luba-Edlina Dubinsky, Research Director and Chair ____________________________________________ Jean-Louis Haguenauer ____________________________________________ Karen Shaw ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my tremendous gratitude to several individuals without whose support I would not have been able to complete this essay and conclude my long pursuit of the Doctor of Music degree. Firstly, I would like to thank my committee chair, Professor Luba Edlina-Dubinsky, for her musical inspirations, artistry, and devotion in teaching. Her passion for music and her belief in me are what motivated me to begin this journey. I would like to thank my committee members, Professor Jean-Louis Haguenauer and Dr. Karen Shaw, for their continuous supervision and never-ending encouragement that helped me along the way. I also would like to thank Professor Evelyne Brancart, who was on my committee in the earlier part of my study, for her unceasing support and wisdom. I have learned so much from each one of you. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Mimi Zweig and the entire Indiana University String Academy, for their unconditional friendship and love. They have become my family and home away from home, and without them I would not have been where I am today. -

The Career of Fernand Faniard

Carrière artistique du Ténor FERNAND FANIARD (9.12.1894 Saint-Josse-ten-Noode - 3.08.1955 Paris) ********** 1. THÉÂTRE BELGIQUE & GRAND DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG BRUXELLES : OPÉRA ROYAL DE LA MONNAIE [1921-1925 : Baryton, sous son nom véritable : SMEETS] Manon [première apparition affichée dans un rôle] 1er & 5 août 1920 Louise (Le Peintre) 2 août 1920 Faust (Valentin) 7 août 1920 Carmen (Morales) 7 août 1920. La fille de Madame Angot (Buteux) 13 avril 1921, avec Mmes. Emma Luart (Clairette), Terka-Lyon (Melle. Lange), Daryse (Amarante), Mercky (Javotte, Hersille), Prick (Thérèse, Mme. Herbelin), Deschesne (Babet), Maréchal (Cydalèse), Blondeau. MM. Razavet (Ange Pitou), Arnaud (Pomponnet), Boyer (Larivaudière), Raidich (Louchard), Dognies (Trénitz), Dalman (Cadet, un officier), Coutelier (Guillaume), Deckers (un cabaretier), Prevers (un incroyable). La fille de Roland (Hardré) 7 octobre 1921 Boris Godounov (création) (Tcherniakovsky), 12 décembre 1921 Antar (création) (un berger) 10 novembre 1922 La victoire (création) (L'envoi) 28 mars 1923 Les contes d'Hoffmann (Andreas & Cochenille) La vida breve (création) (un chanteur) 12 avril 1923 Francesca da Rimini (création) (un archer) 9 novembre 1923 Thomas d'Agnelet (création) (Red Beard, le Lieutenant du Roy) 14 février 1924 Il barbiere di Siviglia (Fiorillo) Der Freischütz (Kilian) La Habanera (Le troisième ami) Les huguenots (Retz) Le joli Gilles (Gilles) La Juive (Ruggiero) Les maîtres chanteurs (Vogelsang) Pénélope (Ctessipe) Cendrillon (Le superintendant) [1925-1926 : Ténor] Gianni Schicchi (Simone) Monna Vanna (Torello) Le roi d'Ys (Jahel) [20.04.1940] GRANDE MATINÉE DE GALA (au profit de la Caisse de secours et d'entr'aide du personnel du Théâtre Royal). Samson et Dalila (2ème acte) (Samson) avec : Mina BOLOTINE (Dalila), Mr. -

Bizet Carmen Mp3, Flac, Wma Related Music Albums To

Bizet Carmen mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Carmen Country: UK Style: Opera MP3 version RAR size: 1148 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1903 mb WMA version RAR size: 1773 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 451 Other Formats: WAV TTA AHX MMF MP3 VOX ADX Label: Decca – LXT 2615 Type: 3 x Vinyl, LP, Mono Country: UK Date of released: Category: Classical Style: Opera Related Music albums to Carmen by Bizet Bizet | Janine Micheau, Nicolai Gedda, Ernest Blanc, Jacques Mars | Chorus And Orchestra Of The Théâtre National De L'Opéra-Comique Conducted By Pierre Dervaux - The Pearl Fishers The Orchestra Of The Paris Opera - Carmen (Highlights) The Rome Symphony Orchestra Under The Direction Of Domenico Savino, Bizet - Carmen Charles Gounod, Georges Bizet, Orchestra Of The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Alexander Gibson - Faust Ballet Music / Carmen Suite Albert Wolff / The Paris Conservatoire Orchestra - Berlioz Overtures Glazunov : L'Orchestre De La Société Des Concerts Du Conservatoire De Paris Conducted By Albert Wolff - The Seasons, Op.67 - Ballet Georges Bizet / Marilyn Horne / James McCracken / Leonard Bernstein / The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra And Chorus - Carmen Bizet | Soloists, Chorus & Orchestra Of The Opéra-Comique, Paris | Albert Wolff - "Carmen" - Highlights Georges Bizet, Maria Callas, Nicolai Gedda, Robert Massard, Andréa Guiot - CARMEN Bizet, Chorus & Orch. Of The Metropolitan Opera Association - Carmen - Excerpts Georges Bizet, Rafael Frühbeck De Burgos, Grace Bumbry, Mirella Freni, Jon Vickers, Kostas Paskalis - Carmen (Highlights) Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Leopold Stokowski, Bizet - Carmen Suite. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Le Journal Musical De Chopin Iddo Bar-Sha

RodolpheAnne Bruneau-Boulmier Queffélec Le journal musical de Chopin Iddo Bar-Sha Le journal musical de Chopin (1810 -1849) Jean-Frédéric Neuburger 1. 1817 Polonaise en sol mineur S 1/1 • Abdel Rahman El Bacha 3’03 2. 1827 Nocturne en mi mineur opus 72 n°1 • Anne Queffélec 4’20 Abdel Rahman El Bacha 3. 1829 Étude n°1 en ut majeur opus 10 • Philippe Giusiano 2’01 4. 1830 Étude n°2 en la mineur opus 10 • Philippe Giusiano 1’23 5. 1830 Étude n°3 en mi majeur opus 10 • Philippe Giusiano 3’45 6. 1832 Mazurka n°3 en la bémol majeur opus 17 • Iddo Bar-Sha 4’37 7. 1833 Mazurka n°4 en la mineur opus 17 • Iddo Bar-Sha 4’31 8. 1838-39 Nocturne en fa majeur opus 15 n°1 • Jean-Frédéric Neuburger 4’16 Anne Queffélec 9. 1837 Scherzo n°2 en si bémol mineur opus 31 • Momo Kodama 9’54 10. 1836-39 Ballade n°2 en fa majeur opus 38 • Jean-Frédéric Neuburger 7’06 11. 1831-39 Prélude n°15 en ré bémol majeur opus 28 • Philippe Giusiano 4’52 Philippe Giusiano 12. 1845-46 Barcarolle en fa dièse majeur opus 60 • Anne Queffélec 9’01 13. 1845-46 Polonaise-Fantaisie en la bémol majeur opus 61 • Abdel Rahman El Bacha 12’04 14. 1846 Mazurka n°3 en ut dièse mineur opus 63 • Iddo Bar-Sha 2’26 15. 1849 Mazurka n°4 en fa mineur opus 68 • Iddo Bar-Sha 2’18 Momo Kodama durée totale : 76’ Le journal musical de Chopin homme séduisant à la silhouette frêle jusqu'au spectre de patrie d'enfance. -

61 CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS and CONFLICT with STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations a Close Friendship Between Arthur Lourié A

CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS AND CONFLICT WITH STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations A close friendship between Arthur Lourié and Igor Stravinsky began once both had left their native Russian homeland and settled on French soil. Stravinsky left before the Russian Revolution occurred and was on friendly terms with his countrymen when he departed; from the premiere of the Firebird (1910) in Paris onward he was the favored representative of Russia abroad. "The force of his example bequeathed a russkiv slog (Russian manner of expression or writing) to the whole world of twentieth-century concert music."1 Lourié on the other hand defected in 1922 after the Bolshevik Revolution and, because he had abandoned his position as the first commissar of music, he was thereafter regarded as a traitor. Fortunately this disrepute did not follow him to Paris, where Stravinsky, as did others, appreciated his musical and literary talents. The first contact between the two composers was apparently a correspondence from Stravinsky to Lourié September 9, 1920 in regard to the emigration of Stravinsky's mother. The letter from Stravinsky thanks Lourié for previous help and requests further assistance in selling items from Stravinsky's 1 Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the 61 62 apartment in order to raise money for his mother's voyage to France.2 She finally left in 1922, which was the year in which Lourié himself defected while on government business in Berlin. The two may have met for the first time in 1923 when Stravinsky's Histoire du Soldat was performed at the Bauhaus exhibit in Weimar, Germany.