The Magazine of Albemarle County History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H. Doc. 108-222

EIGHTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1823, TO MARCH 3, 1825 FIRST SESSION—December 1, 1823, to May 27, 1824 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1824, to March 3, 1825 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—DANIEL D. TOMPKINS, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN GAILLARD, 1 of South Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—CHARLES CUTTS, of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 2 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 3 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland; JOHN O. DUNN, 4 of District of Columbia DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN BIRCH, of Maryland ALABAMA GEORGIA Waller Taylor, Vincennes SENATORS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES William R. King, Cahaba John Elliott, Sunbury Jonathan Jennings, Charlestown William Kelly, Huntsville Nicholas Ware, 8 Richmond John Test, Brookville REPRESENTATIVES Thomas W. Cobb, 9 Greensboro William Prince, 14 Princeton John McKee, Tuscaloosa REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Gabriel Moore, Huntsville Jacob Call, 15 Princeton George W. Owen, Claiborne Joel Abbot, Washington George Cary, Appling CONNECTICUT Thomas W. Cobb, 10 Greensboro KENTUCKY 11 SENATORS Richard H. Wilde, Augusta SENATORS James Lanman, Norwich Alfred Cuthbert, Eatonton Elijah Boardman, 5 Litchfield John Forsyth, Augusta Richard M. Johnson, Great Crossings Henry W. Edwards, 6 New Haven Edward F. Tattnall, Savannah Isham Talbot, Frankfort REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Wiley Thompson, Elberton REPRESENTATIVES Noyes Barber, Groton Samuel A. Foote, Cheshire ILLINOIS Richard A. Buckner, Greensburg Ansel Sterling, Sharon SENATORS Henry Clay, Lexington Ebenezer Stoddard, Woodstock Jesse B. Thomas, Edwardsville Robert P. Henry, Hopkinsville Gideon Tomlinson, Fairfield Ninian Edwards, 12 Edwardsville Francis Johnson, Bowling Green Lemuel Whitman, Farmington John McLean, 13 Shawneetown John T. -

Full Officer Bios

MONTPELIER DESCENDANTS COMMITTEE: FULL OFFICER BIOS Henry Anglin B. Henry Anglin is a founding member of the Montpelier Descendants Committee (MDC) and serves on the MDC Communications and Education Subcommittee. He is also a member of the Montpelier Futures Committee, a cohort of Descendants and Montpelier Foundation board members tasked with addressing parity issues to help ensure a more inclusive narrative. Henry grew up in Orange County’s Jacksontown Community, founded by his great-grandfather who was born on the Newman Plantation at Bloomfield, adjacent to Montpelier; his grandfather worked at Montpelier. He brings experience to his roles from the field of education as a former teacher and supervisor/mentor, and business through extensive experience with academic publishing companies, such as Oxford University Press, among others. He is a retired vice president of Pearson. Henry graduated from George Washington Carver High School in Culpeper, Bowie State University, and earned a graduate degree in education from the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Iris Ford Iris Carter Ford is a professor (emerita) at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, The Public Honors College at Historic St. Mary’s City. Her research and teaching focus on consumption and materialism in Africa and the African Diaspora, and include ethnographic fieldwork in East and West Africa, and archival work at Oxford’s Bodleian Library. She was the recipient of two National Endowment for the Humanities grants to explore materialism in human life, and serves as a Descendant Advisor on a research project, Understanding the Overseer: Examining Status and Identity at James Madison’s Montpelier, also funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. -

A History of St. Mark's Parish, in Which Governor Spotswood Did Not Have a Prominent Place, Would Be Like a Portrait with the Most Prominent Feature Left Out

A HISTORY OF ST. MARK'S PARISH CULPEPER COUNTY, VIRGINIA, WITH NOTES OF OLD CHURCHES AND OLD FAMILIES, AND ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE Manners and Customs of the Olden Time. BY REV. PHILIP SLAUGHTER, D.D. Rector of Emmanuel Church, Culpeper Co.s Va. AUTHOR OF THE HISTORIES OF ST. GSORGB'S AND BRISTOL PARISHES, VA. 1877. IKNES & COMPANY, Printers, BALTIMORE, MO. THE AUTHOR'S PREFACE. The author believes that he was the first person who conceived the idea of writing a history of the old parishes in Yirginia upon the basis of the old vestry-books and registers. Thirty years ago he published the History of Bristol Parish (Petersburg), of which he was then rector. In 1849 he published the History of St. George's Parish, in Spotsylvania. His labors were then suspended by ill-health, and he went abroad, never expecting to resume them. This personal evil resulted in the general good. Bishop Meade, the most competent of all men for this special task, was induced to take up the subject, and the result was the valuable work, " The Old Ohurches and Families of Yirginia," in which the author's histories of St. George and Bristol Parishes, and some other materials which he had gathered, were incorporated. The author, in his old age, returns to his first love, and submits to the public a history of his native parish of St. Mark's. The reader will please bear in mind that this is not a general history of the civil and social institutions within the bounds of this parish, and yet he will find in it many incidental illustrations of these subjects. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1971, Volume 66, Issue No. 3

1814: A Dark Hour Before the Dawn Harry L. Coles National Response to the Sack of Washington Paul Woehrmann Response to Crisis: Baltimore in 1814 Frank A. Cassell Christopher Hughes, Jr. at Ghent, 1814 Chester G. Dunham ^•PIPR^$&^. "^UUI Fall, 1971 QUARTERLY PUBLISHED BY THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY GOVERNING COUNCIL OF THE SOCIETY GEORGE L. RADCLIFFE, Chairman of the Council SAMUEL HOPKINS, President J. GILMAN D'ARCY PAUL, Vice President C. A. PORTER HOPKINS, Vice President H. H. WALKER LEWIS, Vice President EDWARD G. HOWARD, Vice President JOHN G. EVANS, Treasurer MRS. WILLIAM D. GROFF, JR., Recording Secretary A. RUSSELL SLAGLE, Corresponding Secretary HON. FREDERICK W. BRUNE, Past President WILLIAM B. MARYE, Secretary Emeritus CHARLES P. CRANE, Membership LEONARD C. CREWE, Gallery DR. RHODA M. DORSEY, Publications LUDLOW H. BALDWIN, Darnall Young People's Museum MRS. BRYDEN B. HYDE, Women's CHARLES L. MARBURG, Athenaeum ROBERT G. MERRICK, Finance ABBOTT L. PENNIMAN, JR., Athenaeum DR. THOMAS G. PULLEN, JR., Education FREDERICK L. WEHR, Maritime DR. HUNTINGTON WILLIAMS, Library HAROLD R. MANAKEE, Director BOARD OF EDITORS JEAN BAKER Goucher College RHODA M. DORSEY, Chairman Goucher College JACK P. GREENE Johns Hopkins University FRANCIS C. HABER University of Maryland AUBREY C. LAND University of Georgia BENJAMIN QUARLES Morgan State College MORRIS L. RADOFF Maryland State Archivist A. RUSSELL SLAGLE Baltimore RICHARD WALSH Georgetown University FORMER EDITORS WILLIAM HAND BROWNE 1906-1909 LOUIS H. DIELMAN 1910-1937 JAMES W. FOSTER 1938-1949, 1950-1951 HARRY AMMON 1950 FRED SHELLEY 1951-1955 FRANCIS C. HABER 1955-1958 RICHARD WALSH 1958-1967 M6A SC 588M-^3 MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. -

Office of Legal Counsel of The

OPINIONS OF THE OFFICE OF LEGAL COUNSEL OF THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE CONSISTING OF SELECTED MEMORANDUM OPINIONS ADVISING THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, THE ATTORNEY GENERAL AND OTHER EXECUTIVE OFFICERS OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT IN RELATION TO THEIR OFFICIAL DUTIES VOLUME 16 1992 WASHINGTON 1998 Attorney General William P. Barr Assistant Attorney General Office of Legal Counsel Timothy E. Flanigan Deputy Assistant Attorneys General Office of Legal Counsel John E. Barry Douglas R. Cox John C. Harrison David G. Leitch OFFICE OF LEGAL COUNSEL Attomey-Advisers (1992) Barbara E. Armacost Eric Grant Stuart M. Benjamin Rosemary A. Hart Steven G. Bradbury Daniel L. Koffsky Lee A. Casey Herman Marcuse Paul P. Colbom M ark L. Movsesian Peter B. Davidson Eric A. Posner Robert J. Delahunty Alexandra A.E. Shapiro Jacques deLisle Jeffrey K. Shapiro John F. Duffy George C. Smith Mark P. Edelman John J. Sullivan James E. Gauch Susan J. Swift Todd F. Gaziano FOREWORD The Attorney General has directed the Office of Legal Counsel to publish selected opinions on an annual basis for the convenience of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the government, and of the professional bar and the general public. The first fifteen volumes of opinions published covered the years 1977 through 1991; the present volume covers 1992. The opinions included in Volume 16 include some that have previously been released to the public, additional opinions as to which the addressee has agreed to publication, and opinions to Department of Justice officials that the Office of Legal Counsel has determined may be released. -

Nomination Form ------·---~

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF SHE INTERIOR (3s~.1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM -----------·---~----------------- ,, (Clleelt 9ne) Excellent 0 Good O Fair D Oelerioroled 0 Ruins lxJ Unexposed 0 (Cheek One) (Check One) GillT Y Altered G9 Unaltered D Moved D Original Site ~ CRISE THE PRESl;.NT ANO ORIGINAL (II known) PHYSICAi.. APPEARANCE Until it burned on Christmas day, 1884, James Barbour's house at Barboursvil e stood essentially as completed circa 1822 from designs by Thomas Jefferson. Only two one-story side porches appear to have been later additions. Though large in scale, the house contained only eight principal rooms, the hall, drawing room, and dining room being two-story chambers •.The entrance facade featured a projecting Roman Doric tetrastyle portico which covered the reces ed front wall of the entrance hall. On the garden front the walls of the octagonal drawing room projected into a similar portico, as at Monticello. The octagonal dome which Jefferson proposed in his drawing was omitted during construction; it is uncertain whether the Chinese lattice railing whi h appeared in Jefferson's drawing around the base of the roof was ever install d. Although the dining room had no chamber over it, Jefferson indicated a false window on the second floor level in order to keep the garden front symmetrical. This feature was omitted and consequently gave that side of the house an unbalanced appearance. Unfortunately, there is little V, evidence as to the appearance of the original interior architectural trim. m One might assume that the two-story rooms were crowned by full entablatures m as at Monticello. -

Confederate Street Renaming Pilot Program Policy and Procedures

PLANNING AND ZONING DEPARTMENT CONFEDERATE STREET RENAMING PILOT PROGRAM POLICY AND PROCEDURE 2021/2022 Effective August 10, 2021 PURPOSE AND AUTHORITY The purpose of this policy and pilot program is to provide standard procedures for street renaming requests for roadways bearing the names of Confederate soldiers and leaders (see attachment). This pilot program provides guidance for renaming of up to three streets. Upon completion of renaming three streets, the Naming Committee will reevaluate the procedures or discontinue the program. Authority for street naming and renaming is defined by City Code Sec. 5-2-66 - Ordinance required for change of street name which states that, "The name of any street designated by the official naming map referred to in section 5-2-63 of this code or by subsequent designation by the planning commission shall not be changed except by the adoption of an ordinance by the city council. (Code 1963, Sec.33-46)". POLICY STATEMENTS Requesting a name change for roadways classified as an arterial and expressway, local, primary collector, residential collector, alley, or unnamed alley For any roadway identified on the Inventory of Confederate Street Names – June 2021 list, a petitioner is allowed to complete and submit a Street Name Change application through the Alexandria Permit and Planning portal (APEX) which includes a petition signed by a minimum of 25% of property owners with addresses along the roadway. For an alley, the petition should include signatures from property owners with addresses along the alley and owners with addresses from abutting properties that might not be addressed off the alley. -

Nomination Form

Unfiftsd Slator Dapmrtmmnt of tha IMar P!etional Park Ssrv~ca Natlonel Register of Hletorlc Places Registration Form Thlr hm rm br mn nmnrthrg ar mhg a( w~bllhybr IndMdull wowtlw w dm.?W Mwtbu In Iw &mpklhg NHlanU RmW Fbma [N&honaRNnn Bulkrtn $8). Cawnch Hm by mrrklrlng "r" In thr ma!.aa* a b.Imtvkrg hm H~WM~hmmm17 m ~*m rwrt tcl IM wng dlxurmrrtd. rnnr "Mh"IM "far001kNM." FD~fumba. w,m, and Irmb Ot o~gnrflcrne*.mlmr only thm eatppn and 6mv-w Irfld In Zhr I I ~ For~ lddnlOn&! . Ipl# uW rnnt!lwllW (Form 70-1). Typ* oll mtrln. - - 7. Nmm* of Pmparty hi5tonc mma -~;rmlrw t fil~no. 68-104 2. Locatlm~pprnxirrratel~31,200-xr-a hrd~rwltm-i -8: the north.I-1~ romm L"otfor~M~pI~a c~rj,town 1 1 w nn the cn~ri-h -nil t-h~rTr~-5t.. 4i.JI ' Ylclnlty stet* Vsrqpnla code dounty ~ra~ap as377 tip W 77971 - -- Aa tnr doatgnats autharhy under the Pllmtlonal HLltarlc Pmarvrtlon An a! IPW, ur#rWd, 1 hereby csntfy th~tIhk 9norn17at1anL; rsquan ~dtdsYmEnltlOn at ~IQIMI~tr tths dmmms~brundlrdm tar mptmtsrlng prom- In w r ot nlrtorlc Pfmar md mrra Ihr pm~~dural mnd prol+#bnrl rqulremrntl Ht brth In 30 CFCl Pnfl61). Edm not mwl tba NMnml Rqmr cm#rlm. mnutbn nn. 1 A - ,- 14 Not/ l9CiQ Dmr of Historic Resources - WMESTIC TTC slnqle dwellinq sin- multlple dwellinq e secondarv structure hotel storaae e t Architectural Classification Materials (enter categories from instructions) (enter categories trom instructions) foundatin WCOD NQ STYrE walls IAL shlnale C~o~an roof 1- BRICK see continwtion sheet other Describe present and historic physical appearance. -

Nomination Form Frascati, Orange County, Virginia Continuation Sheet Tl Item Number 6

.. = - - United States Department of the interior '?!-A > Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service For HCRS use only .. t b tecslved Nationail Register of Historic Places , i date entered . 1~~~entoay-310minatienForm -. X \", - .< .'l._ See instructions in How to Complete Nafionaf Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections Name historic---- Frascgi - and/or common Frascati 2, Location street&number State Route 231, south of Somerset- -no5 for publicati~n Seventh city, town Somerset Jvicinity of congressional district (J. Kenneth Robinson) .- -- - -- state Virg inin code f 1 county Orange code 137 - -... - . - - -- - - . .. 3, Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use - district -public -2-l occupied -agriculture -museum x buildingIs) 2 private -unoccupied -commerciat -park -structure both workin progress educational 25- private residence -- . site Public Acquisition Accessibk -entertainment -religious -object -in process _x yes: restricted -government -sclentiff~ -being considered - yes: unrestricted -industrial -transportation -no -military -other: 4. Owner of Paoperay -. mfl.5 J5/4//JG/%'fl&d& P. Woodriff, TI, Somersgt, Va.22972 M. Smith, Esq. 1151, Charlottesville, Va, 22902 elty, town . vicinity of state 5. Locaiiiom of Lena! Description courthouse,registry of deed< cte, ---- Orange Count-y Courthouse--- street & number --.- -+ Zip Code city, town Orange state Virginia 22960 8. Representation in Existing Surveys m (see CO~~,~,,~,, ,bet#I, title (1) Historic berican- - ., - .. - this property been determined eleglble? -. yes -no ~ ~ i l =surve,asd f ~ ~ - - date 1958 Inventory 1957 a- federal -state -county -local -- -- -- -- -- --.- - depository--- for survey records Library of Congress - citv. fnwn Washin~t on sfata n r 7. Description Condition Check one Check one 2 excellent deteriorated -unaltered ,original site -good -ruins _x. -

VIRGINIA BARBERS (1) ABRAHAM C BARBER, Lee

VIRGINIA BARBERS (1) ABRAHAM C BARBER, Lee Co. (2) DAVID of Pittsylvania Co (3) Other Pittsylvania Co Barbers (4) EDWARD BARBER, Culpeper Co VA to Bath Co KY (5) EDWARD BARBOUR of VA and KY (6) ELISHA DYER of Pittsylvania Co VA and KY (7) JAMES BARBOUR OF VIRGINIA and KENTUCKY (8) JAMES MESSER of Halifax Co VA, TN and KY (9) JOHN and EDWARD BARBER/BARBOUR of Stafford Co VA (10) SETH BARBER of Henry Co VA (11) THOMAS BARBOUR of Mecklenberg Co VA and Miami Co OH (12) WILLIAM of Richmond Co (1) ABRAHAM C BARBER, Lee Co. From William Gordon Mullins at Rootsweb Worldconnect 1 ABRAHAM C BARBER, b: OCT 1837; m Rachel E HARRIS; r Rose Hill, Lee Co VA. Abraham is possibly son of Barbary Barber. 2 SARAH JANE, b: AUG 1866 d: 1939; m Brownlow Matlock; r Hagan, Lee Co. 2 MARTHA E, b: 11 NOV 1868 d: 20 JUN 1948; m Samuel A Milwee; r Hagan. 2 ALEXANDER, b: 8 JUL 1869 d: 20 NOV 1901; m Nancy Minerva Ellis; r Rose Hill, Lee Co VA. 3 FRANCES, b: 2 FEB 1889 d: 20 NOV 1901 3 ELIZABETH, b: JUL 1891; r Harlan Co KY; d Lee Co; m David Fee. 3 THOMAS M, b: 11 NOV 1893 d: 27 NOV 1954; m Martha E Shupe; r Hagan, Lee Co. 4 THOMAS L, b: 26 OCT 1917 d: 26 OCT 1917 4 CARL H, b: 1 JAN 1920 d: Lee Co 3 JUL 1988; m ---Gregory. 5 Sharon, ; m --- Black. 5 Jerry, m --- Willis. -

Virginia Wineries: Top Three Day Trip Destinations by KW Rosenfeld

http://voices.yahoo.com/shared/print.shtml?content_type=artic... Close Window Click here to print or select File then Print from your browser. Virginia Wineries: Top Three Day Trip Destinations By KW Rosenfeld Virginia's wine industry is considered to be among the finest in the country, making good on the vision of Founding Father Thomas Jefferson who persistently but unsuccessfully attempted wine-making more than 200 hundred years earlier. Now among the nation's most prolific wine-producing states, and rapidly building a reputation across the globe, Virginia receives acclaim for the quality of its wines and the character of its wineries. Today, the rolling hills are overflowing with exceptional wineries, particularly in the regions surrounding Jefferson's Charlottesville and to the north outside of Leesburg. But travel a little out of the way and additional gems can be found. These wineries not only produce great wine, but offer the exceptional atmosphere and surrounding attractions that promise to turn a pleasant visit into a memorable day trip. Contact each winery for the latest details on hours and events. Paradise Springs Winery - Northern Virginia 13219 Yates Ford Road; Clifton, Virginia 20124 www.paradisespringswinery.com Notable as the only winery in populous Fairfax County outside of Washington, DC, Paradise Springs is nestled in a quiet, forested area near the quaint town of Clifton. A newcomer, having planted its first vineyard in 2008, the family-run winery opened in January 2010, after prevailing in a lengthy zoning dispute in which it had to prove that the winery was more "agricultural" than "industrial." Wine award: The 2009 Chardonnay won the prestigious Governor's Cup as the best white wine in the Commonwealth. -

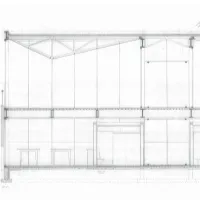

Barboursville Ruins Abstract

barboursvillet h i n k i n g w i t h i n a r c h i t e c t u ruinsr e t h i n k i n g w i t h i n a r c h i t e c t u r e Thesis submitted to the faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture. blacksburg, virginia november 2002 ____________________________________________________ v. hunter pittman, chairman _____________________________________________________ william w. brown ____________________________________________________ william u. galloway c l a u d i a h a r r i s o n abstract With historic ruins as a project vehicle, this thesis investigates connections to an existing structure through materials and spatial relationships. The proposed intervention, guided by design elements and preservation methods, reflects a sensitive approach and provides a transition between our built heritage and an adapted form of architecture. acknowledgement. With sincere gratitude, I wish to acknowledge those people whose support and friendship have made this experience possible. my thesis committee (hunter pittman, bill brown, bill galloway): for their guidance and encouragement throughout the masters program and their special vision for this project. my cowgill hall colleagues: for the sense of community that I felt in studio and the experiences we shared in discovering architecture. my son (josh sahrmann): for his love and continued support, and the many sacrifices made during these years in virginia. my friends: for their patience and support in helping me realize this important goal. Thank you for opening my eyes to many new possibilties.