PIRANESI BETWEEN CLASSICAL and SUBLIME (1) Fatma İpek EK and Deniz ŞENGEL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Note: Surface Water Velocity Observations from a Camera: a Case Study on the Tiber River

Supplement of Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 11, 11883–11904, 2014 http://www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/11/11883/2014/ doi:10.5194/hessd-11-11883-2014-supplement © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Supplement of Technical Note: Surface water velocity observations from a camera: a case study on the Tiber River F. Tauro et al. Correspondence to: S. Grimaldi ([email protected]) PUBLICATIONS Water Resources Research RESEARCH ARTICLE Orienting the camera and firing lasers to enhance large scale 10.1002/2014WR015952 particle image velocimetry for streamflow monitoring Key Points: Flavia Tauro1,2,3, Maurizio Porfiri1, and Salvatore Grimaldi1,3,4 Camera is oriented with its axis perpendicular to the water surface 1Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, New York University Polytechnic School of Engineering, Field of view calibration through a Brooklyn, New York, USA, 2Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile, Edile e Ambientale, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, system of lasers Italy, 3Honors Center of Italian Universities, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy, 4Dipartimento per l’Innovazione nei LSPIV accuracy is improved by relating velocity data to tracer Sistemi Biologici, Agroalimentari e Forestali, University of Tuscia, Viterbo, Italy density Abstract Large scale particle image velocimetry (LSPIV) is a nonintrusive methodology for continuous Correspondence to: S. Grimaldi, surface flow monitoring in natural environments. Recent experimental studies demonstrate that LSPIV is a [email protected] promising technique to estimate flow discharge in riverine systems. Traditionally, LSPIV implementations are based on the use of angled cameras to capture extended fields of view; images are then orthorectified Citation: and calibrated through the acquisition of ground reference points. -

Storia Degli Scavi Di Roma E Notizie Intorno Le Collezioni Romane Di Antichit

RODOLFO LANCIA NI STORIA DEGLI SCAVI DI ROMA E NOTIZIE INTORNO LE COLLEZIONI ROMANE DI ANTICHITÀ Volume Primo (a. 1000-15 30) ROMA ERMANNO LOESCHER & C.» (bretschneider e regenberg) Librai-Editori di S. M. la Regina d'Italia 1902 ROMA TIPOGRAFIA DELLA R. ACCADEMIA DEI LINCEI PROPRIETÀ DEL CAV. V. SALVIUCCI 1902 RODOLFO LANgiANI ' STORIA ^ DEGLI SCAVI DI ROMA E NOTIZIE INTORNO LE COLLEZIONI ROMANE DI ANTICHITÀ Volume Primo (a. 1000-15 50) ROMA ERMANNO LOESCHER & C.o (breischneider e regenberg) l.ibrai-Hditori di S. M. la Regina d'Italia 1902 • AUTORE SI RISERVA IL DIRITTO DI PROPRIETÀ LETTERARIA A TENORE DI LEGGE Edizione di 500 esemplari. ROMA TIPOGRAFIA DELLA R. ACCADEMIA DEI LINCEI PROPRIETÀ DEL CAV. V. SALVIUCCI 1902 PREFAZIONE Il primo volume della Storia degli scavi e de' musei di Roma che presento agli studiosi di queste materie, comprende il periodo decorso dagli inizii del secolo XI al pontificato di Clemente VII (1530). Gli altri quattro volumi, coi quali spero condurre detta storia sino al 1870, usciranno a intervalli di un anno. Scopo di questo lavoro, pel quale ho impiegato venticinque anni di pre- parazione bibliografica e archivistica, è quello di presentare un quadro possi- bilmente completo delle ricerche e delle scoperte di antichità fatte in Roma e sue vicinanze dal mille in poi : come pure di dare notizie inedite o pocn conosciute suUa formazione e dispersione delle raccolte romane d'arte e di antichità. Con l'aiuto di queste notizie, che sono accompagnate dalle licenze d'esportazione rilasciate dalla Camera Apostolica sin dalla seconda metà del secolo XVI, si potrà forse ritrovare l' origine e riconoscere le vicende di mol- tissime opere d' arte, provenienti da Roma, che oggi adornano i musei del resto dell'Italia e dell'Europa. -

The Italian Archaeological Heritage: a Ciassification of Types from the Point of View

Proceedings of the First International Congress on Construction History, Madrid, 20th-24th January 2003, ed. S. Huerta, Madrid: I. Juan de Herrera, SEdHC, ETSAM, A. E. Benvenuto, COAM, F. Dragados, 2003. The italian archaeological heritage: a cIassification of types from the point of view. Of protection against earthquakes D. Liberatore G. Spera A. Claps A. Larotonda A classi1'ication 01' types 01' the Italian archaeological The classi1'ication 01' types, centred on the heritage is presented. The classi1'ication is centred on structural behaviour, is presented in this study. the structural behaviour and is the basis 1'or Twenty-two types are considered which comprehend subsequent studies on seismic vulnerability and risk. the heritage 01' prehistoric, Etruscan, Greek and Twenty-two types are considered which comprehend Roman Ages. For each type, there are given a the heritage 01' prehistoric, Etruscan, Greek and description 01' the structural elements and a [ist 01' Roman Ages. For each type, there are given a sites -unavoidably non-exhaustive- where description 01' the structural elements and a list 01' specimens 01' the type are present which are clearly sites where specimens 01'the type are present. recognizabJe, in the sense that they are not included in later bui Idings. The list does not include those sites where the presence 01' ancient constructions is INTRODUCTION documented by historical or literary sources only. Some types, like the Doric temple, are subdivided Recent Italian destructive earthquakes (Friuli 1976, into sub-types depending on the different behaviour Irpinia 1980 and Umbria-Marche 1997) had a heavy 01'the remains under earthquake. -

RELIGIÃO ROMANA EM LIVROS DIDÁTICOS BRASILEIROS Jorwan Gama Da Costa Junior TEMA LIVRE

Volume 2, Número 2 - Outubro de 2016 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE (UFF) INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS E FILOSOFIA (ICHF) PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA (PPGH) NÚCLEO DE ESTUDOS DE REPRESENTAÇÕES E DE IMAGENS DA ANTIGUIDADE (NEREIDA) REVISTA HÉLADE - ISSN: 1518-2541 ANO 2, VOLUME 2, NÚMERO 2 URL: www.helade.uff.br OUTUBRO DE 2016 E-mail: [email protected] Campus do Gragoatá - Rua Prof. Marcos Waldemar de Freitas Reis, Bloco O, sala 507. Cep: 24210-201 - Niterói - RJ EDITORES Prof. Dr. Alexandre Santos de Moraes (Editor-chefe) - Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) Profa. Dra. Adriene Baron Tacla - Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) Prof. Dr. Alexandre Carneiro Cerqueira Lima - Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) SÉRIE ANTIGA ASSISTENTES DE EDIÇÃO Volume 1, Número 1 - 2000 Volume 1, Número 2 - 2000 Grad. Thaís Rodrigues dos Santos - Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) Volume 2, Número 1 - 2001 Grad. Geovani dos Santos Canuto- Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) Volume 2, Número 2 - 2001 Volume 2, Número Especial - 2001 Volume 3, Número 1 - 2002 CONSELHO EDITORIAL Volume 3, Número 2 - 2002 Profa. Dra. Ana Livia Bomfim Vieira - Universidade Estadual do Maranhão (UEMA) Volume 4 - 2003-2004 Profa. Dra. Ana Teresa Marques Gonçalves - Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) Volume 5 - 2005 Profa. Dra. Claudia Beltrão da Rosa - Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO) Prof. Dr. Fábio Faversani - Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto (UFOP) Prof. Dr. Fábio de Souza Lessa - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) Prof. Dr. Gilvan Ventura da Silva - Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES) Prof. Dr. José Antônio Dabdab Trabulsi - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) Profa. -

The Aniene River As a Green Infrastructure… Between Roma and Tivoli

INTERNATIONAL STUDIES INTERDISCIPLINARY POLITICAL AND CULTURAL JOURNAL, Vol. 19, No. 1/2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ipcj-2017-000329–44, DOI: 10.1515/ipcj-2017-0003 Biancamaria Rizzo*1 POLICY-MAKING IN METROPOLITAN AREAS: THE ANIENE RIVER AS A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE… BETWEEN ROMA AND TIVOLI ABSTRACT: The European policies acknowledge greenways and “Green Infrastructure” as strategically planned and delivered networks comprising the broadest range of green spaces and other environmental features. The Aniene River, linking the eastern suburbs of Rome to the City of Tivoli, has been envisaged in a multi-level approach as a Green-Blue Infrastructure able to hinder land use fragmentation and provide new continuity to remainders of open space. In turn, landscape is taken into account as a biodiversity reservoir, the scenery of outstanding cultural heritage and the relevant backdrop of ordinary life. KEYWORDS: Green Infrastructure, urban fringe, urban planning, urban design, urban governance, Aniene River. The European framework The European landscape, more than any other, has suffered a huge loss of natural habitats because of the fragmentation of land uses and landscapes due to human activities and infrastructure. Such processes, resulting in an alarming decrease in many wildlife populations, are likely to jeopardise biodiversity conservation. Lately, although the main natural areas are now largely protected by the Natura 2000 Network,1 2 new concerns have been raised * Department of Architecture, “Roma Tre” University of Rome; Largo Giovanni -

On Rivers Flowing Into Tideless Seas, Illustrated By

2 SHELFORD ON NON-TIDALRIVERS. [Minutes of Associate Members. HAROLDWILLIAM ABERNETHY. 1 EDWARDGLOVER, M.A., B.E. JCSTINVICTOR WILFRID AMOR. HVGHERAT HARRISON, B.Sc. JOSEPHDEVONPORT PINNEY AND~EWS.CHRISTOPHER LITTLE, Stud. Inst.C.E. ANDREWGEORGE ASHCROFT,Stud. GEORGEVINCENT MAXTED, Stud. Inst. C.E. Inst. C.E. ROBERT AYTOWN. MICHAEL NETHERSOLE,Stud. Inst. C.E. WILLIAM CHRISTOPHER BARLEY. WILLIAMBAKER OLLIS. WILLIAMBEAN. HENRYOUGH. HARRYJOHN TOLEB BENNETT. ERKESTSAMUEL PRENTICE, Stud. Inat. CHARLESHENRY BLACKBURN, Stud. C.E. Inst. C.E. ERNESTVAN PUTTEN, Stud. Inst. C.E. FRANKBREWER, Stud. Inst.C.E. THOMASNOBLE RITSON. The Hon. REGINALDTHOBIAS DUDLEY JOHNPEMBERTON STUBBS. BROUGHAM, ARCHIBALD ALEXANDER SWAN. MATTHEWJOSEPH BUTLER. PERCYTARBUTT. WILLIAM BUTTERTON,Jun. SAMTOMLINSON, Stud. Inst. C.E. JAMESCAMERON. GEORGE-WATEEYS. ALBERTJOHNSTONE CAMPBELL. Associates. HENRYSPEWER PALMER, Lieut.-CoL, KOWROJEEPESTONJEE. R.E. I THEOPHILUSGEORGE WRIGHT. (Paper No. 2069.) “ On Rivem flowing into Tideless Seas, illustrated by the River Tiber.” By WILLIAMSRELFORD, M. Inst. C.E. TREtreatment of tidal rivers, as distinguished from that of rivers running into tideless seas, isparticularly a British subject. Not only is the seaboard of GreatBritain and Ireland far greater than that of any other country in Europe, but the shores of the British possessions abroad are for the most part washed by tidal seas.Moreover, the earlier Presidents of The Institution of Civil Engineers, and those who developed the profession of Civil Engi- neering in England, advanced -

The Fall of Rome in Collapse Theory

51 NEXUS: The Canadian Student Journal ofAnthropology, Vol. 11: 51·69 (1993) Look upon my works, ye mighty, and despair: the fall of Rome in collapse theory. Ronald A. Ross Department ofArchaeology & Prehistory University ofSheffield ABSTRACT: Several recent works have attempted to deal with the collapse of all past state societies, including the Western Roman EmpiJ:e, as specific instances of a universal systemic phenomenon. These works all subscribe to a common list of characteristics of collapse, emphasizing poverty and discontinuity. This article examines the historical genesis of the concept of the fall of the Roman Empire, and modern scholarship on the Late Antique·Early Medieval transition. The 'trait list' of collapse is shown not to apply to the 'fall' of Rome. For centuries, even millennia, travellers have looked in awe on the ruins of past civilizations. Struck by fallen grandeur, they have wondered what could have brought the creators ofthese mighty edifices to such a pitiful condition. With time, uninformed speculation has been replaced with a large body of scholarly work. Numerous more or less coherent theories have been put forward to explain the indiVidual collapses of the Indus Valley civilization (c.1800 B.C.) the Mycenean Empire (c.1200 B.C.), Ivrinoan Crete (c. 1450 B.C.), the Hittites (c.1200 B.C.), Sixth Dynasty Egypt (c. 2150 B.C.), Chou China (c.771 B.C.), the Classical Maya (cAD.1200), and the Roman Empire (cAD.500). The more reputable among these theories (those not involving, say, aliens or sinking continents) have ranged from geological and climatic changes (i.e. -

The Making of Medieval Rome Hendrik Dey Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-83853-5 — The Making of Medieval Rome Hendrik Dey Index More Information INDEX Adelspapsttum, 171, 186 aqua alessandrina, 283 Porta Tiburtina (S. Lorenzo), 107, 253, Adeodatus, Pope, 87 Aqua Antoniniana, 24 257 Aëtius, Flavius, general, 52 Aqua Claudia, 22, 91, 115, 120, 146, Aurelian, Emperor, 23 Agatho, Pope, 273 147–8, 151 Aventine Hill, 40, 162, 228–30 Aistulf, King of the Lombards, 110 Aqua Jovia (Iobia), 91, 115, 137, 151 Avignon, removal of papacy to, 8–9, 213, Alaric I, King of the Visigoths, 36 Aqua Marcia-Tepula-Julia, 283 217 sacks Rome in 410, 37 Aqua Sabbatina. See aqueducts: Aqua Avitus, Emperor, 54 Alberic I, Duke of Spoleto, 141 Traiana Alberic II, princeps Romanorum, 142, 148, Aqua Traiana, 20, 75, 91, 115, 137, 164, Ballardini, Antonella, 119 159, 167, 294 273 baptisteries, 29 Alberti, Leon Battista, 257–8 Aqua Virgo, 18, 91, 115, 137, 252 Lateran, 77, 193 Albinus, urban prefect, 42 Arcadius, Emperor, 37 S. Anastasia, 265 Alexander II, Pope, 172, 189 archaeology, medieval S. Vitale, 265 Alexander III, Pope, 2, 196 methods and practices, 5–6, 41, 89, 144, SS. Quattro Coronati, 265, 295 Alexander IV, Pope, 238 201–4, 219 Barbarossa. See Frederick I, King/Emperor Alexander V, Pope, 253 arches, triumphal, 37 barons (barones Urbis), 213–16, 253 Alfanus camerarius, 194, 200 Arcionii family, 187 urban strongholds of, 228–34 Amalasunta, Queen of the Ostrogoths, 64, arcus Constantini, 20 Bartolo da Sassoferrato, 301 66 Argiletum, 127, 131, 203 Basilica Aemilia, 15, 39, 44, 55, 62, 75, 133, Ammianus Marcellinus, 25 ascesa Proti, 159 202 Anacletus II, antipope, 195, 297, 298 Athalaric, King of the Ostrogoths, 66 basilica argentaria, 16 Anastasius, Cardinal, 192–4 atrium Libertatis, 43, 62 Basilica Hilariana, 40, 178 Anastasius, Pope, 85 atrium Minervae, 11, 46 Basilica Julia, 15, 44, 134 Annibaldi family, 187, 215, 253, 302 Aula Gotica, 236–8 basilica nova. -

Wilhelm Osthues: Bauwissen Im Antiken Rom

Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Studies 4 Wilhelm Osthues: Bauwissen im Antiken Rom In: Jürgen Renn, Wilhelm Osthues and Hermann Schlimme (Hrsg.): Wissensgeschichte der Architektur : Band II: Vom Alten Ägypten bis zum Antiken Rom Online version at http://edition-open-access.de/studies/4/ ISBN 978-3-945561-03-4 First published 2014 by Edition Open Access, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science under Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 Germany Licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/de/ Printed and distributed by: Neopubli GmbH, Berlin http://www.epubli.de/shop/buch/42160 The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Kapitel 3 Bauwissen im Antiken Rom Wilhelm Osthues 3.1 Historische und gesellschaftliche Rahmenbedingungen der Entwicklung der rö- mischen Architektur Keine Beschäftigung mit der römischen Architektur kann ein einigermaßen nachvollzieh- bares Bild ergeben ohne Rekurs auf die römische Geschichte. Rom, in archaischer Zeit ei- ne kleines, von den Etruskern abhängiges Gemeinwesen, hat sich durch seine militärische Expansion praktisch alle Ressourcen erschlossen, über die die Mittelmeerwelt der Antike verfügen konnte – die Materialien, die Arbeitskräfte, die Finanzmittel, und nicht zuletzt das Wissen der besten Architekten seiner Zeit. Ohne diese Expansion wäre die Entwicklung der römischen Architektur, wie sie uns vorliegt, nicht vorstellbar. Rom hatte aber nicht nur die Machtmittel, die Ressourcen nahezu der gesamten Mittel- meerwelt für sich zu nutzen, es hatte auch die Bereitschaft, kulturelle Leistungen anderer zu adaptieren. Schon Cicero hat offen eingeräumt, dass in weiten Bereichen der Wissenschaft und der Kunst die Griechen den Römern überlegen waren. -

A Case Study of Spatial-Temporal Rainfall Disaggregation at the Tiber River, Italy

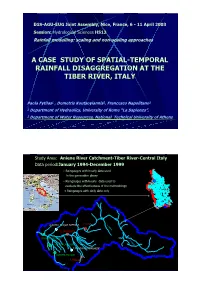

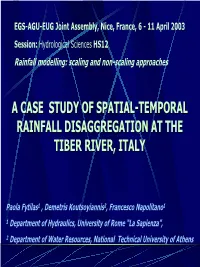

EGS-AGU-EUG Joint Assembly, Nice, France, 6 - 11 April 2003 Session: Hydrological Sciences HS12 Rainfall modelling: scaling and non-scaling approaches A CASE STUDY OF SPATIAL-TEMPORAL RAINFALL DISAGGREGATION AT THE TIBER RIVER, ITALY Paola Fytilas1 , Demetris Koutsoyiannis2, Francesco Napolitano1 1 Department of Hydraulics, University of Rome “La Sapienza”, 2 Department of Water Resources, National Technical University of Athens Study Area:Area Aniene River Catchment-Tiber River-Central Italy Data period:January 1994-December 1999 • Raingauges with hourly data used in the generation phase • Raingauges with hourly data used to evaluate the effectiveness of the methodology • Raingauges with daily data only F . A nie ne 1.TIVOLI F . 8.ROMA ACQUA ACETOSA A n ie ne 2.L UNGHEZZA io riv F b . m A Si ni . e T ne 4.PONTE SALARIO F . A n F i . A e n i e 5.ROMA FLAMINIO ne ne 7.PANTANO BORGHESE 6.ROMA MACAO 3. FRASCATI The Methodology Observed DAILY data at Observed several points HOURLY data at several points Marginal statistics (d) Marginal statistics (h) Temporal Correlation(d) Temporal Correlation(h) Spatial Correlation (d) Spatial Correlation (h) Spatial-temporal Multivariate Simplified COUPLING Rainfall model or Point rainfall model TRANSFORMATION empirical expression AR(1) disaggregation for cross-correlation coefficients Synthetic Hourly Synthetic Hourly Data at several Data at several points points (not consistent (consistent with daily with daily amounts) amounts) Parameter Estimation Essential statistics to preserve in the generated hourly series : 1.the means, variances and coefficients of skewness; 2.the temporal correlation structure (autocorrelations); 3.the spatial correlation structure (lag zero cross-correlations); and 4.the proportions of dry intervals. -

A Case Study of Spatial-Temporal Rainfall Disaggregation at the Tiber River Basin, Italy

EGS-AGU-EUG Joint Assembly, Nice, France, 6 - 11 April 2003 Session: Hydrological Sciences HS12 Rainfall modelling: scaling and non-scaling approaches AA CASECASE STUDYSTUDY OFOF SPATIALSPATIAL--TEMPORALTEMPORAL RAINFALLRAINFALL DISAGGREGATIONDISAGGREGATION ATAT THETHE TIBERTIBER RIVER,RIVER, ITALYITALY Paola Fytilas1 , Demetris Koutsoyiannis2, Francesco Napolitano1 1 Department of Hydraulics, University of Rome “La Sapienza”, 2 Department of Water Resources, National Technical University of Athens with hourly data used Aniene River Catchment-Tiber River-Central Italy Anie ne F. F. A ni ene io r iv b m S i . Raingauges T • F. Aniene :January 1994-Decemberinin thethe generationgeneration phasephase 1999 F. Ani ene Raingauges with hourly data used to F. Aniene • evaluate the effectiveness of the methodology Raingauges with daily data only StudyStudy Area:Area • DataData periodperiod 1.TIVOLI 2.L UNGHEZZA 8.ROMA ACQUA ACETOSA 7.PANTANO BORGHESE 3. FRASCATI 5.ROMA FLAMINIO 4.PONTE SALARIO 6.ROMA MACAO TheThe MethodologyMethodology Observed DAILY data at Observed several points HOURLY data at several points Marginal statistics (d) Marginal statistics (h) Temporal Correlation(d) Temporal Correlation(h) Spatial Correlation (d) Spatial Correlation (h) Spatial-temporal Multivariate Simplified COUPLING Rainfall model or Point rainfall model TRANSFORMATION empirical expression AR(1) disaggregation for cross-correlation coefficients Synthetic Hourly Synthetic Hourly Data at several Data at several points points (not consistent (consistent with daily with daily amounts) amounts) ParameterParameter EstimationEstimation Essential statistics to preserve in the generated hourly series : 1.the means, variances and coefficients of skewness; 2.the temporal correlation structure (autocorrelations); 3.the spatial correlation structure (lag zero cross-correlations); and 4.the proportions of dry intervals. -

Ciclopedalata “Su E Giu' Per I Ponti Di Roma”

CICLOPEDALATA “SU E GIU’ PER I PONTI DI ROMA” (Ponte della Musica>Ponte Milvio>Ponte Flaminio> Ponte Salario>Ponte Nomentano > Ponte Milvio) Escursione cicloturistica poco impegnativa che si sviluppa prevalentemente sulle piste ciclabili urbane lungo i fiumi Tevere e Aniene, aperta a partecipanti di tutte le età anche senza una particolare esperienza ciclistica. Si consiglia l’utilizzo di Mountain Bike o City Bike o bici da corsa con copertoncini da 25”. Data: domenica 16 febbraio 2014 Ritrovo per la partenza: Roma – Ingresso del Museo del Genio in Lungotevere della Vittoria 31 (adiacente Piazza Maresciallo Giardino) dalle ore 09.00 alle 09.30. È possibile raggiungere la partenza in auto (ampie possibilità di parcheggio per le automobili sul Lungotevere della Vittoria), in metropolitana (linea A, stazione Ottaviano e di lì pista ciclabile lungo via Barletta e viale Angelico fino a piazza Maresciallo Giardino – 1,6 km) e, ovviamente, in bicicletta. Partenza: ore 09.30 Orario previsto di rientro: ore 13.00 / 13.30 1 Percorso* : Lungotevere della Vittoria, Piazza Maresciallo Giardino, Via Capoprati, Piazzale di Ponte Milvio, Ponte Milvio, Lungotevere dell’Acqua Acetosa, via dei Campi Sportivi, via dell’Agonistica, viale della Moschea, via del Foro Italico, via Salaria, via Prato della Signora, Pista ciclabile dell’Aniene, via dei Campi Flegrei, via Val Trompia, via Valsolda, via Nomentana, Ponte Tazio, Piazza Sempione, via Maiella, via Nomentana, Ponte Nomentano, via Val Trompia, via Campi Flegrei, Pista ciclabile dell’Aniene, via Prato della Signora, via Salaria, via del Foro Italico, Viale della Moschea, via dell’Agonistica, via dei Campi Sportivi, Lungotevere dell’Acqua Acetosa, Ponte Milvio, Piazzale di Ponte Milvio, via Capoprati, Piazza Maresciallo Giardino, Lungotevere della Vittoria.