Electric Motor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Motor Primer - Part 5

A MOTOR PRIMER - PART 5 Copyright Material IEEE Paper No. PCIC 2005-9 Bryan Oakes Gary Donner Senior Member, IEEE Fellow, IEEE Rockwell Automation Shell Oil Products US 101 Reliance Road 2101 E Pacific Coast Hwy Kings Mountain, NC 28086 Wilmington, CA 90748 USA USA [email protected] [email protected] Steve Evon Wayne Paschall Senior Member, IEEE Member, IEEE Rockwell Automation Rockwell Automation 6040 Ponders Ct. 101 Reliance Road Greenville, SC 29615 Kings Mountain, NC 28086 USA USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract - In recent years much has been written II. WHAT PURPOSE DOES PERFORMING A about motors concerning efficiencies, vibration TORSIONAL ANALYSIS SERVE AND WHEN IS and resonance conditions as they relate to the IT REQUIRED? WHAT OCCURS DURING A American Petroleum Institutes (API) Standard TORSIONAL RESONANT CONDITION? 541 and motor diagnostics. Most of these papers and articles assume that the reader has Torsional vibration is an oscillatory twisting of significant knowledge of motor theory and the shaft. A motor by design applies a torsional operation. However, this assumption is overly force to the driven equipment and the driven optimistic, considering that only a few colleges equipment applies an equal and opposite force teach motor theory today and that application back to the motor. The shaft system deflects in experience at motor user locations has been torsion or twists away from the free position. At reduced in recent years. free vibration, and at its natural frequencies, the twist is free to unwind, twisting back to the free Index Terms – AC Induction Motors, position and, if undamped, twist an equal amount Efficiency, Torsional, Lateral Critical Speed, in the opposite direction. -

Cahier Technique No. 207

Collection Technique .......................................................................... Cahier technique no. 207 Electric motors ... and how to improve their control and protection E. Gaucheron Building a New Electric World "Cahiers Techniques" is a collection of documents intended for engineers and technicians, people in the industry who are looking for more in-depth information in order to complement that given in product catalogues. Furthermore, these "Cahiers Techniques" are often considered as helpful "tools" for training courses. They provide knowledge on new technical and technological developments in the electrotechnical field and electronics. They also provide better understanding of various phenomena observed in electrical installations, systems and equipments. Each "Cahier Technique" provides an in-depth study of a precise subject in the fields of electrical networks, protection devices, monitoring and control and industrial automation systems. The latest publications can be downloaded from the Schneider Electric internet web site. Code: http://www.schneider-electric.com Section: Press Please contact your Schneider Electric representative if you want either a "Cahier Technique" or the list of available titles. The "Cahiers Techniques" collection is part of the Schneider Electric’s "Collection technique". Foreword The author disclaims all responsibility subsequent to incorrect use of information or diagrams reproduced in this document, and cannot be held responsible for any errors or oversights, or for the consequences of using information and diagrams contained in this document. Reproduction of all or part of a "Cahier Technique" is authorised with the compulsory mention: "Extracted from Schneider Electric "Cahier Technique" no. ....." (please specify). no. 207 Electric motors ... and how to improve their control and protection Etienne Gaucheron Graduate electronics engineer by training. -

N O T I C E This Document Has Been Reproduced From

N O T I C E THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED FROM MICROFICHE. ALTHOUGH IT IS RECOGNIZED THAT CERTAIN PORTIONS ARE ILLEGIBLE, IT IS BEING RELEASED IN THE INTEREST OF MAKING AVAILABLE AS MUCH INFORMATION AS POSSIBLE gg50- y-^ 3 (NASA-CH-163584) A STUDY OF TdE N80 -32856 APPLICABILITY/COMPATIbIL1TY OF INERTIAL ENERGY STURAGE SYSTEMS TU FU'IUAE SPACE MISSIONS Firnal C.eport (Texas Univ.) 139 p Unclas HC A07/MF AJ1 CSCL 10C G3/44 28665 CENTER FOR ELECTROMECHANICS OLD ^ l ^:' ^sA sit ^AC^utY OEM a^ 7//oo^6^^, THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING TAYLOR NAIL 167 AUSTIN, TEXAS, 71712 512/471-4496 4l3 Final Report for A Study of the Applicability/Compatibility of Inertial Energy Storage Systems to Future Space Missions Jet Propulsion Laboratory ... Contract No. 955619 This work was {performed for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology Sponsored by The National Aeronautics and Space Administration under Contract NAS7-100 by William F. Weldon r Technical Director Center for Electromechanics The University of Texas at Austin Taylor Hall 167 Austin, Texas 18712 (512) 471-4496 August, 1980 t c This document contains information prepared by the Center for Electromechanics of The University of Texas at Austin under JPL sub- contract. Its content is not necessarily endorsed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, or its sponsors. QpIrS r^r^..++r•^vT.+... .. ...^r..e.^^..^..-.^...^^.-Tw—.mss--rn ^s^w . ^A^^v^T'^'1^^w'aw^.^^'^.R!^'^rT-.. _ ..,^.wa^^.-.-.^.w r^.-,- www^w^^ -- r f Si i ABSTRACT The applicability/compatibility of inertial energy storage systems, i.e. -

Evaluation of Direct Torque Control with a Constant-Frequency Torque Regulator Under Various Discrete Interleaving Carriers

electronics Article Evaluation of Direct Torque Control with a Constant-Frequency Torque Regulator under Various Discrete Interleaving Carriers Ibrahim Mohd Alsofyani and Kyo-Beum Lee * Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Ajou University, 206, World cup-ro, Yeongtong-gu Suwon 16499, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-31-219-2376 Received: 25 June 2019; Accepted: 20 July 2019; Published: 23 July 2019 Abstract: Constant-frequency torque regulator–based direct torque control (CFTR-DTC) provides an attractive and powerful control strategy for induction and permanent-magnet motors. However, this scheme has two major issues: A sector-flux droop at low speed and poor torque dynamic performance. To improve the performance of this control method, interleaving triangular carriers are used to replace the single carrier in the CFTR controller to increase the duty voltage cycles and reduce the flux droop. However, this method causes an increase in the motor torque ripple. Hence, in this work, different discrete steps when generating the interleaving carriers in CFTR-DTC of an induction machine are compared. The comparison involves the investigation of the torque dynamic performance and torque and stator flux ripples. The effectiveness of the proposed CFTR-DTC with various discrete interleaving-carriers is validated through simulation and experimental results. Keywords: constant-frequency torque regulator; direct torque control; flux regulation; induction motor; interleaving carriers; low-speed operation 1. Introduction There are two well-established control strategies for high-performance motor drives: Field orientation control (FOC) and direct torque control (DTC) [1–3]. The FOC method has received wide acceptance in industry [4]. Nevertheless, it is complex because of the requirement for two proportional-integral (PI) regulators, space-vector modulation (SVM), and frame transformation, which also needs the installation of a high-resolution speed encoder. -

Direct Torque Control of Induction Motors

DIRECT TORQUE CONTROL FOR INDUCTION MOTOR DRIVES MAIN FEATURES OF DTC · Decoupled control of torque and flux · Absence of mechanical transducers · Current regulator, PWM pulse generation, PI control of flux and torque and co-ordinate transformation are not required · Very simple control scheme and low computational time · Reduced parameter sensitivity BLOCK DIAGRAM OF DTC SCHEME + _ s* s j s + Djs _ Voltage Vector s * T + j s DT Selection _ T S S S s Stator a b c Torque j s s E Flux vs 2 Estimator Estimator 3 s is 2 i b i a 3 Induction Motor In principle the DTC method selects one of the six nonzero and two zero voltage vectors of the inverter on the basis of the instantaneous errors in torque and stator flux magnitude. MAIN TOPICS Þ Space vector representation Þ Fundamental concept of DTC Þ Rotor flux reference Þ Voltage vector selection criteria Þ Amplitude of flux and torque hysteresis band Þ Direct self control (DSC) Þ SVM applied to DTC Þ Flux estimation at low speed Þ Sensitivity to parameter variations and current sensor offsets Þ Conclusions INVERTER OUTPUT VOLTAGE VECTORS I Sw1 Sw3 Sw5 E a b c Sw2 Sw4 Sw6 Voltage-source inverter (VSI) For each possible switching configuration, the output voltages can be represented in terms of space vectors, according to the following equation æ 2p 4p ö s 2 j j v = ç v + v e 3 + v e 3 ÷ s ç a b c ÷ 3 è ø where va, vb and vc are phase voltages. -

DRM105, PM Sinusoidal Motor Vector Control with Quadrature

PM Sinusoidal Motor Vector Control with Quadrature Encoder Designer Reference Manual Devices Supported: MCF51AC256 Document Number: DRM105 Rev. 0 09/2008 How to Reach Us: Home Page: www.freescale.com Web Support: http://www.freescale.com/support USA/Europe or Locations Not Listed: Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. Technical Information Center, EL516 2100 East Elliot Road Tempe, Arizona 85284 1-800-521-6274 or +1-480-768-2130 www.freescale.com/support Europe, Middle East, and Africa: Freescale Halbleiter Deutschland GmbH Technical Information Center Information in this document is provided solely to enable system and Schatzbogen 7 software implementers to use Freescale Semiconductor products. There are 81829 Muenchen, Germany no express or implied copyright licenses granted hereunder to design or +44 1296 380 456 (English) fabricate any integrated circuits or integrated circuits based on the +46 8 52200080 (English) information in this document. +49 89 92103 559 (German) +33 1 69 35 48 48 (French) www.freescale.com/support Freescale Semiconductor reserves the right to make changes without further notice to any products herein. Freescale Semiconductor makes no warranty, Japan: representation or guarantee regarding the suitability of its products for any Freescale Semiconductor Japan Ltd. particular purpose, nor does Freescale Semiconductor assume any liability Headquarters arising out of the application or use of any product or circuit, and specifically ARCO Tower 15F disclaims any and all liability, including without limitation consequential or 1-8-1, Shimo-Meguro, Meguro-ku, incidental damages. “Typical” parameters that may be provided in Freescale Tokyo 153-0064 Semiconductor data sheets and/or specifications can and do vary in different Japan applications and actual performance may vary over time. -

Motors for Ship Propulsion

Motors for Ship Propulsion The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Kirtley, James L., Arijit Banerjee, and Steven Englebretson. “Motors for Ship Propulsion.” Proc. IEEE 103, no. 12 (December 2015): 2320– 2332. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2015.2487044 Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/102381 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ > REPLACE THIS LINE WITH YOUR PAPER IDENTIFICATION NUMBER (DOUBLE-CLICK HERE TO EDIT) < 1 Motors for Ship Propulsion James L. Kirtley Jr., Fellow, IEEE, Arijit Banerjee, Student Member, IEEE and Steven Englebretson, Member, IEEE machines but these are 'long shots' in the competition for use Abstract—Electric propulsion of ships has experienced steady in ship propulsion. expansion for several decades. Since the early 20th century, There is a substantial advantage in having a motor that icebreakers have employed the flexibility and easy control of DC can drive the propeller of a ship directly, not requiring a speed motors to provide for ship operations that split ice with back and reducing gearbox, and we will focus on such motors in this forth motion of the ship. More recently, cruise ships have paper. Shaft speeds range from about 100 to about 200 RPM employed diesel-electric propulsion systems to take advantage of for large ships, and power ratings per shaft range from about the flexibility of diesel, as opposed to steam engines, and because the electric plant can also be used for hotel loads. -

Research and Development of a High-Resolution Piezoelectric Rotary Stage

KAUNAS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY IGNAS GRYBAS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT OF A HIGH-RESOLUTION PIEZOELECTRIC ROTARY STAGE Doctoral Dissertation Technological Sciences, Mechanical Engineering (09T) 2017, Kaunas This doctoral dissertation was prepared at Kaunas University of Technology, Institute of Mechatronics during the period of 2013–2017. The studies were supported by the Research Council of Lithuania. Scientific Supervisor: Habil. Dr. Algimantas Bubulis, (Kaunas University of Technology, Technological Sciences, Mechanical Engineering, 09T). Doctoral dissertation has been published in: http://ktu.edu Editor: Dovilė Dumbrauskaitė (Publishing Office “Technologija”) © I. Grybas, 2017 ISBN xxxx-xxxx The bibliographic information about the publication is available in the National Bibliographic Data Bank (NBDB) of the Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania KAUNO TECHNOLOGIJOS UNIVERSITETAS IGNAS GRYBAS AUKŠTOS SKYROS PJEZOELEKTRINIO SUKAMOJO STALIUKO KŪRIMAS IR TYRIMAS Daktaro disertacija Technologiniai mokslai, mechanikos inžinerija (09T) 2017, Kaunas Disertacija rengta 2013–2017 metais Kauno technologijos universiteto Mechatronikos institute. Mokslinius tyrimus rėmė Lietuvos mokslo taryba. Mokslinis vadovas: Habil. dr. Algimantas Bubulis (Kauno technologijos universitetas, technologiniai mokslai, mechanikos inžinerija, 09T). Interneto svetainės, kurioje skelbiama disertacija, adresas: http://ktu.edu Redagavo: Dovilė Dumbrauskaitė (leidykla “Technologija“) © I. Grybas, 2017 ISBN xxxx-xxxx Leidinio bibliografinė informacija pateikiama -

Modeling, Analogue and Tests of an Electric Machine

MODELING, ANALOGUE AND TESTS OF AN ELECTRIC MACHINE VOLTAGE CONTROL SYSTEM 'by GRAHAM E.' DAWSON ( j B.A.Sc, University of British. Columbia, 1963. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS, FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF APPLIED SCIENCE. in the Department of Electrical Engineering We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard Members of the Committee Head of the Department .»»«... Members of the Department of Electrical Engineering THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1966 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely.avai1able for reference and study. I further agree that permission for ex• tensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives.. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for finan• cial gain shall not be allowed without my.written permission. Department of Electrical Engineering The University of British Columbia Vancou ve r.,8, Canada Date 7. MM ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the modeling, analogue and tests of an interconnected four electric machine voltage control system. Many analogue studies of electric machines have been done but most are concerned with the development of analogue techniques and only a few give substantiation of the validity of the analogue models through comparison of results from analogue studies and from real machine tests. Chapter 2 describes the procedure and the system under study. Chapter 3 describes the methods used for the determination of the electrical and mechanical system parameters. -

Background Information

Background information Nuremberg, November 3, 2016 A powerful driving force for 150 years The discovery of the dynamo-electric principle has brought about greater changes to the way our society lives than practically any other scientific breakthrough. By inventing the dynamo machine, not only did Werner von Siemens help bring about the advent of electrical machinery, he was also instrumental in accelerating and facilitating industrial processes. Seen from the perspective of society, this completely changed accepted concepts of time and mobility. Werner von Siemens was consequently justified in the confidence he expressed in concluding his report to the Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1867 with the words: “Technology now has the means to generate electrical current of unlimited strength in an inexpensive and convenient way wherever mechanical energy is available.” The first dynamo machines were then also used for the generation of electricity for “light and for galvanic metallurgy and for small electromagnetic machines that get their power from large ones” (Werner von Siemens). 18 years later, Nikola Tesla and Galileo Ferraris independently discovered that alternating currents displaced in time generated a rotating magnetic field with the ability to move an armature. Based on this work, in 1889 the head engineer at AEG, Michail von Dolivo-Dobrowolski, developed the first usable asynchronous motor, whose principle still forms the basis of 85 percent of all practical drive applications today, according to the ZVEI. Siemens AG Wittelsbacherplatz 2 Communications 80333 Munich Head: Clarissa Haller Germany Seite 1/11 Siemens AG Background information Fig. 1: Structure of the dynamo machine This discovery paved the way for mechanizing heavy work such as rolling, drilling, milling and grinding in factory halls. -

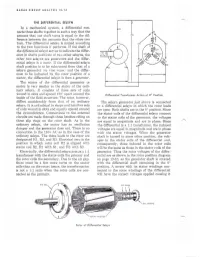

In a Mechanical System, a Differential

RADAR CIRCUIT ANALYSIS 13-14 THE DIFFERENTIAL SElSYN In a mechanical system, a differential con- 52 nects three shafts together in such a way that the amount that one shaft turns is equal to the dif- zsv ference between the amounts that the other two turn. The differential selsyn is named according to the two functions it performs. If the shaft of the differential selsyn serves to indicate the differ- ence in shafts positions of two other selsyns, the other two selsyns are generators and the differ- ential selsyn is a motor. If the differential selsyn shaft position is to be subtracted from that of a 53 selsyn generator (or vice versa) and the differ- ence to be indicated by the rotor position of a i----OV---o-i motor, the differential selsyn is then a generator. ~---OV--~~_-4 ~ The stator of the differential generator or motor is very similar to the stator of the ordi- nary selsyn. It consists of three sets of coils 0 wound in slots and spaced 120 apart around the Differential Transformer Action at 0° Position inside of the field structure. The rotor, however, differs considerably from that of an ordinary The selsyn generator just above is connected selsyn. It is cylindrical in shape and has three sets to a differential selsyn in which the rotor leads of coils wound in slots and equally spaced around are open. Both shafts are in the 0° position. Since the circumference. Connections to the external the stator coils of the differential selsyn connect circuits are made through three brushes riding on to the stator coils of the generator, the voltages three slip rings on the rotor shaft. -

Dynamic Analysis of a Piezoelectric Ultrasonic Motor with Application to the Design of a Compact High-Precision Positioning Stage

Department of Precision and Microsystems Engineering Dynamic analysis of a piezoelectric ultrasonic motor With application to the design of a compact high-precision positioning stage Name: Teunis van Dam Report no: ME 11.036 Coach: R. Ellenbroek Professor: prof. ir. R. H. Munnig Schmidt Specialization: Mechatronics Type of report: Masters Thesis Date: Delft, November 22, 2011 2 3 Preface This thesis describes the work I have done at Mapper Lithography B.V. in Delft, as a final project for my masters Precision and Microsystems Engineering at Delft University of Technology, faculty 3mE. This project is part of the process of designing a high-precision linear positioning stage for a wafer scanner using electron beam lithography. The first part of my work is focused on the conceptual design of this stage, in which choosing the actuator type plays a dominant role. The second and largest part is focused on detailed analysis of the dynamic behavior of the selected actuator, a piezoelectric ultrasonic motor, by building a simulation model of the motor and validating this model by experiments. I want to thank my professor, Robert Munnig Schmidt, and my supervisor at Mapper Lithography, Rogier Ellenbroek, for their support and valuable feedback on my work. Furthermore I would like to thank my design leader at Mapper Lithography, Jerry Peijster, and my other colleagues, for granting me this opportunity and for the pleasant cooperation. Teunis van Dam Contents 1 Introduction 6 1.1 General introduction . 6 1.2 Machine description and problem statement . 6 1.3 Overviewofcontents......................................... 7 2 Stage requirements 9 2.1 Functionality .