Ice Station a Scarecrow Novel the DISCOVERY of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eclectic Antiquity Catalog

Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes © University of Notre Dame, 2010. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-9753984-2-5 Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 Geometric Horse Figurine ............................................................................................................. 5 Horse Bit with Sphinx Cheek Plates.............................................................................................. 11 Cup-skyphos with Women Harvesting Fruit.................................................................................. 17 Terracotta Lekythos....................................................................................................................... 23 Marble Lekythos Gravemarker Depicting “Leave Taking” ......................................................... 29 South Daunian Funnel Krater....................................................................................................... 35 Female Figurines.......................................................................................................................... 41 Hooded Male Portrait................................................................................................................... 47 Small Female Head...................................................................................................................... -

Emmerson Denney

Toronto: 416.504.9666 EMMERSON DENNEY Vancouver: 604.744.0222 Los Angeles: 310.584.6606 PERSONAL MANAGEMENT Montreal: 1.888.652.0204 [email protected] TORONTO ••• VANCOUVER ••• LOS ANGELES www.emmerson.ca DIANE PITBLADO, B.A., M.F.A. (ACTRA/CAEA) Dialect/Voice Coach Film and Television American Gods Ricky Whittle Fremantle/David Slade Conviction Hayley Atwell ABC/ Liz Friedlander American Gothic Stephanie Leonidas CBS xXx: The Return… Donnie Yen Revolution/D.J. Caruso Suicide Squad Margot Robbie Warner Bros/David Ayres (plus Cara Delevingne; Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje) Defiance (season 3) Stephanie Leonidis Universal Secret Life of Marilyn… (miniseries) Kelli Garner, Emily Watson Lifetime/ Laurie Collyer Idol’s Eye (prep) Robert Pattinson Benaroya Pictures ROOM Brie Larson, Sean Bridgers Film4 Hannibal (Season 3) Mads Mikkelsen NBC/various God & Country Jake Croker Shaftesbury Films Aaliyah: Princess of R&B (MOW) Izaak Smith Lifetime/Bradley Walsh Regression lead cast Weinstein/Alejandro Amenábar (including Ethan Hawke; Emma Watson; David Dencik; Lothaire Bluteau) Bomb Girls (MOW) Tahmoh Penikett Muse The Girl King entire cast Galafilm-Triptych /Mika Kaurismäki (including Malin Buska; Sarah Gadon; Michael Nyqvist) Maps to the Stars (prep) Mia Wasikowska Prospero Pictures Hannibal (Season 2) Mads Mikkelsen NBC/various Hemlock Grove (Season 2) Dougray Scott Gaumont/various Defiance (Season 2) Stephanie Leonidis Universal Played (eps 111) Noam Jenkins; Liane Balaban Muse/Grant Harvey Pompeii lead cast FilmDistrict/Paul W.S. Anderson (including Emily Browning, Carrie-Anne Moss, Paz Vega, Sasha Roiz ) Saving Hope (eps 203) Raoul Baneja NBC/various Hannibal (Season 1) Mads Mikkelsen NBC/various Hemlock Grove (Season 1) Dougray Scott, Bill Skarsgard Gaumont/Eli Roth Defiance (Season 1) Stephanie Leonidis Universal Bomb Girls Tahmoh Penikett Muse/various XIII (eps 208) Camilla Scott Prodigy Pictures/Rachel Talalay Rewind (MOW) Keisha Castle-Hughes Universal Cable Resident Evil: Retribution (ADR) Li Bingbing Davis Films/Paul W.S. -

Selected Credits

Anne Dixon Costume Designer - Wardrobe Selected Credits: Costume Designer Anne, Season 1 Producer: Miranda de Pencier, Sue 2016-2017 Northwood Anne Inc. Murdoch, Moira Walley-Beckett Television Series Director: Various Production Manager: Teresa Ho Director of Photography: Bobby Shore Production Designer: Jean-Francois Campeau Costume Designer Our House Producer: Lee Kim, Marty Katz, Karen 2016 Our House Films Canada Inc. Wookey Feature Director: Anthony Scott Burns Production Manager: Sam Jephcott Director of Photography: Anthony Scott Burns Production Designer: Naz Goshtasbpour Costume Designer Shoot The Messenger, Producer: Jennifer Holness, Sudz 2015 Season 1 Sutherland, Victoria Woods Television Series Shoot the Messenger Director: Various Productions 1 Inc. Production Manager: Nancy Jackson Director of Photography: Arthur Cooper Production Designer: Rupert Lazarus Costume Designer Lavender Producer: Dave Valleau Lavender Films Inc. Director: Ed Gass-Donnelly Feature Production Manager: Aaron Barnett Director of Photography: Brendan Stacey Production Designer: Oleg Savitsky Costume Designer Born to Be Blue Producer: Jennifer Jonas, Leonard BTB Blue Productions Ltd. Farlinger, Robert Budreau Feature (NOHFC) Director: Robert Budreau Production Manager: Avi Federgreen Production Designer: Aidan Leroux Costume Designer Total Frat Movie Producer: Robert Wertheimer, Neil Digerati Films Inc. Bregman Feature Director: Warren Sonoda Production Manager: Kym Crepin Production Designer: Brian Verhoog Costume Designer Working the Engles, Season -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

MATTHEW REILLY UNIVERSE a Jumpchain CYOA

MATTHEW REILLY UNIVERSE A Jumpchain CYOA Welcome to the shared universe of Matthew Reilly’s novels. You, visitor, are at the tip of the spear. This world of high stakes, nail-biting action needs heroes like you, now more than ever, to defend its people from forces that would seek to control it for their own ends. To explain a little more about the world you’ve stumbled into, to the vast bulk of humanity the world is quite mundane; your average citizen has as roughly the same concept of their world as you or I, and it would be quite easy to live your life as though nothing was any different. Yet behind the curtain, many wheels are in motion. Intelligence organisations and Special Forces units clash in exotic locations – Antarctic research labs, overgrown ruins, secret military facilities – often where highly unusual discoveries are made and where the most daring come away with the prize. Heavily-armed bounty hunters and Private Military Corporations chase lucrative contracts across the world for money and glory; careless of international law and often any collateral damage. In uncharted wilds, hidden cultures and tribes who have never been exposed to the modern world protect secrets from the forgotten past and carry out the rites of their forefathers to this day. Shadowy groups steer the courses of governments with hidden hands. Conspiracies of hate and enlightenment both grow inky webs throughout the military-industrial complex and permeate universities, corporations, the government and other institutions. And behind even these secret manipulators lie great mysteries which continue to shape the world as we know it after many thousands of years, and which may spell its doom...or its salvation. -

QUEERING the SCRIPT 93 Minutes / CANADA

QUEERING THE SCRIPT 93 minutes / CANADA Written and Directed by Gabrielle Zilkha ** OFFICIAL SELECTION – 2019 Inside Out LGBT Film Festival ** ** OFFICIAL SELECTION – 2019 Frameline43 ** Recipient of the Frameline Completion Fund ** OFFICIAL SELECTION – 2019 Outfest LGBT Film Festival ** Winner of the Special Programming Award for Freedom ** OFFICIAL SELECTION - AGLIFF 2019 ** ** OFFICIAL SELECTION – RAINDANCE FILM FESTIVAL 2019 ** Queering the Script is produced by Shaftesbury with the participation of Hollywood Suite, the Canada Media Fund, the Frameline Completion Fund, and with the assistance of The Canadian Film or Video Tax Credit and The Ontario Film and Television Tax Credit. Logline: Giving queer fandom a voice in the conversation about LGBTQ+ representation from “Xena” to “The L Word” to “Pose”, QUEERING THE SCRIPT examines the rising power of the fans and audience shaping representation on TV, the relationship between fandom and activism, and what lies ahead for visibility and inclusiveness. Synopsis: Queerness on television has moved from subtext, in series such as “Xena: Warrior Princess”, to all- out multi season relationships between women, as seen on “Buffy the Vampire Slayer”, “Lost Girl”, and “Carmilla”. But things still aren’t perfect. In 2016, a record number of queer women died on fictional shows, which broke the hearts of queer fans and launched a successful fight for better, more diverse LGTBQ2S+ representation. Stars such as Ilene Chaiken, Stephanie Beatriz, Lucy Lawless and Angelica Ross join with the voices of numerous kickass fangirls in this fast-paced history of queer women’s representation of contemporary television. QUEERING THE SCRIPT not only charts the evolution of queerness, but also demonstrates the extraordinary impact of activism on its many diverse fans, ensuring that they see themselves accurately portrayed on screen. -

(EFF) Passive Wi-Fi Monitoring Futu

Fri 8/29 10:00 A 11:30 A 1:00 P 2:30 P 4:00 P 5:30 P 7:00 P 8:30 P 10:00 P 11:30 P 201 (Hil) (EFF) Passive Wi-Fi Future of Fan Geocaching Remembering Revenge Porn TPB AFK In Defense of ISPs and Six Interracial Monitoring Fiction & and Location- Aaron Swartz and Online Strikes Discourse in Amateur Based Games Reputation- Pseudonyms Erotic Fiction Destroying Romance 202 (Hil) (SCI) The Genetics of Personalized Fun in Fusion The Human Neurogenetics: Of Your Lying Multiple- Cryonics: 2013 X-Men Genomics Research Body: A Mice and Men Eyes partner Updates/Open Walking Petri Families Disc. Dish w/Children 203 (Hil) (POD) Podcast Track How to Make comedy4cast Technorama Kick Off! Money with LIVE! Live! Your Podcast 204-207 (Hil) (SKEP) Skeptrack Kick Secrets of Why Mensa Don't Panic! It's Not News, Every Skeptic Has Skepticism Fictional Quiz-O-Tron Off 2013 Skeptic History Will Never Again... It's Fark a Story 101 Writing and 2000 Solve World Skepticism Hunger 309-310 (Hil) (SPACE) LiftPort Rises Life & Times at Don't Call Me XCor: Another You Won't Go There's an Curiosity, Year Reusable Bad Things Live from the Ashes JPL Dear, Call Me Vision of Crazy Asteroid With 1 Launch Happen to Astronomy (4 PhD.octor Commercial Earth's Name on It Vehicles Be a Good Galaxies Hrs) Space Reality? 311-312 (Hil) (WKS) RJ Haddy: Make-up Out of Kit Human Guinea Pigs (2.5 Hrs) Tai Chi Workshop Workshop (2.5 Hrs) A601-A602 (M) (MAIN) Bill Corbett, An Hour with Farscape: Same Getting The Work of Friday Night Costuming Contest 9:00 Lightspeed Dating (2.5 Hrs) Unlicensed Life Charlie Dren, Different Hatched! Michael Frith Pre-judging Setup/Light- Coach Schlatter Planet (2.5 Hrs) Speed Dating Reg. -

The Danish Girl

March-April 2016 VOL. 31 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES NO. 2 IN THIS ISSUE The Danish Girl | ALA Notables | The Brain | Spotlight on Fitness | Emptying the Skies | The Mama Sherpas | Chi-Raq | Top Spin scene & he d BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Le n more about Bak & Taylor’s Scene & He d team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified buyers ensure titles are available and delivered on time DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music shelf-ready specifications SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging expertise 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review The Danish Girl is taken aback. Married for six years, Einar enjoys a lusty conjugal life with Gerda—un- HHH1/2 til, one day, she asks him to don stockings, Universal, 120 min., R, DVD: $29.98, Blu-ray: tutu, and satin slippers to fill in for a miss- ing model. Sensing his delight in posing in Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.98, Mar. 1 Eddie Redmayne feminine finery, she suggests Einar attend a Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood followed up his Os- party, masquerading as a cousin named Lili. Copy Editor: Kathleen L. Florio car-winning turn as What neither of them expects is that demure Lili will attract amorous attention. -

Treasures of Egypt with Optional 3-Night Jordan Post Tour Extension March 20 – April 1, 2019

State Farm Employee Activities/Goldtimers presents… Treasures of Egypt with Optional 3-Night Jordan Post Tour Extension March 20 – April 1, 2019 Book Now & Save $300 Per Person For more information contact Direct Travel, formerly known as Suzi Davis Travel 309-834-3739 or 866-592-0455 [email protected] Day 1: Wednesday, March 20, 2019 Overnight Flight Step back in time and explore thousands of years of history, legend and lore as you view Egypt’s timeless wonders. Day 2: Thursday, March 21, 2019 Cairo, Egypt - Tour Begins Begin your journey in Cairo, an ancient city with an intriguing past. Day 3: Friday, March 22, 2019 Cairo - Giza - Sakkara - Memphis - Cairo Fulfill a lifelong dream! This morning we travel to nearby Giza where we’ll meet a local archaeologist who will lead us on a visit to the Pyramids of Giza, one of the seven ancient wonders of the world. Marvel at the iconic Great Sphinx, one of the oldest and largest monuments in the world. This afternoon, travel south to Sakkara. Explore the site of ancient Memphis, home to a nearly 40-foot statue of Ramses II, and stand before the oldest of all pyramids, the Step Pyramid. This evening, enjoy a special welcome dinner overlooking the banks of the Nile. (B, D) Day 4: Saturday, March 23, 2019 Cairo - Luxor Spend the morning discovering the remarkable collections of the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities. See the statues, reliefs, sarcophagi and the treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamun himself. Later, we transfer to the airport for our flight to Luxor. -

Area 7 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

AREA 7 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matthew Reilly | 512 pages | 17 Feb 2003 | St Martin's Press | 9780312983222 | English | New York, United States Area 7 PDF Book Schofield gets back to Area 7, but the prisoners that were there for scientific research get out, and make the remaining Air Force and Marines fight to the death. Return to Play Activities Waiver. Apr 30, Alex rated it it was amazing Shelves: in Original Title. Please reference the Developmental Disabilities Services Coverage and Limitations Handbook for more details on services offered under this program. Friday 9 October Forever glad the bears survived. Thursday 20 August Bellingham Bay Fishery see 1 below for boundaries Aug. This is the second book I've read by Matthew Reilly and just like Ice Station the first book in the Scarecrow series it's an action packed read from start to finish! Most of these people die. Melbourne , Victoria , Australia. Monday 29 June Parahippocampal gyrus anterior Entorhinal cortex Perirhinal cortex Postrhinal cortex Posterior parahippocampal gyrus Prepyriform area. Friday 29 May And in the process, he wrote a story that definitely gave me something to worry about. Shane Schofield 4 books. Why, because they have access to many of the installations containing some of this countries greatest tactical assets: high tech planes and ballistic missiles. Area 7 Shane Schofield 2 by Matthew Reilly. For smelt: Jig gear may be used 7 days a week. Sunday 5 July Visual cortex 17 Cuneus Lingual gyrus Calcarine sulcus. Trump trailing behind Biden in funding, weeks before Election Day, new filings show. This book SHOULD be read only if you are waiting in the airport to catch a long-delayed flight, or while pursuing some other similar pursuit. -

The Hero's Helmet

About Jack West Jr and the Hero’s Helmet Jack West Jr. Adventurer. Scholar. Warrior. He is known for his cool head under pressure . and also for the battered fireman’s helmet he has worn throughout his adventures. This is the story of how he got it. BEWARE OF THE HALF TRUTH. YOU MAY HAVE GOTTEN HOLD OF THE WRONG HALF. UNKNOWN THE TEMPLE OF DENDUR South of Aswan, Egypt Source: Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection (via Wikipedia) 1 THE TEMPLE OF DENDUR 8:35 P.M. 24 DECEMBER 1994 Night had fallen by the time Jack West Jr was able to erect his high stepladder and get up close to the roof of the stone temple. He peered at a single crumbling 2,000-year-old sandstone brick. It was weathered and worn yet oddly beautiful. It was one of eight such bricks that ran along the roofline of the gate of the Egyptian Temple of Dendur. Peering closer, Jack saw it, and his heart almost skipped a beat. There, in the top left corner of the brick, was the inscription that he had based his entire thesis upon: a tiny shepherd’s crook hewn into the off-yellow stone. He couldn’t believe he was about to do this. If what he had postulated was true, then it would make his name in the world of international archaeology . and he was only twenty-five. He gazed at the stone brick that surmounted the Egyptian tem- ple’s entrance and for the hundredth time wondered if there was indeed something embedded within that lone brick— ‘Mommy! I wanna go home!’ a child’s voice said from some- where nearby and Jack turned from his perch. -

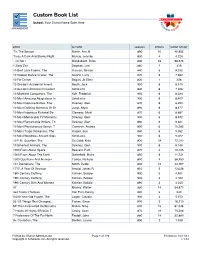

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R.