Ttu Mac001 000024.Pdf (6.728Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great's Tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, Eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Geomorphology 100 (2008) 377–400 www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Alexander the Great's tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N. Marriner a, , J.P. Goiran b, C. Morhange a a CNRS CEREGE UMR 6635, Université Aix-Marseille, Europôle de l'Arbois, BP 80, 13545 Aix-en-Provence cedex 04, France b CNRS MOM Archéorient UMR 5133, 5/7 rue Raulin, 69365 Lyon cedex 07, France Received 25 July 2007; received in revised form 10 January 2008; accepted 11 January 2008 Available online 2 February 2008 Abstract Tyre and Alexandria's coastlines are today characterised by wave-dominated tombolos, peculiar sand isthmuses that link former islands to the adjacent continent. Paradoxically, despite a long history of inquiry into spit and barrier formation, understanding of the dynamics and sedimentary history of tombolos over the Holocene timescale is poor. At Tyre and Alexandria we demonstrate that these rare coastal features are the heritage of a long history of natural morphodynamic forcing and human impacts. In 332 BC, following a protracted seven-month siege of the city, Alexander the Great's engineers cleverly exploited a shallow sublittoral sand bank to seize the island fortress; Tyre's causeway served as a prototype for Alexandria's Heptastadium built a few months later. We report stratigraphic and geomorphological data from the two sand spits, proposing a chronostratigraphic model of tombolo evolution. © 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Tombolo; Spit; Tyre; Alexandria; Mediterranean; Holocene 1. Introduction Courtaud, 2000; Browder and McNinch, 2006); (2) establishing a typology of shoreline salients and tombolos (Zenkovich, 1967; The term tombolo is used to define a spit of sand or shingle Sanderson and Eliot, 1996); and (3) modelling the geometrical linking an island to the adjacent coast. -

Thyrea, Thermopylae and Narrative Patterns in Herodotus Author(S): John Dillery Source: the American Journal of Philology, Vol

Reconfiguring the Past: Thyrea, Thermopylae and Narrative Patterns in Herodotus Author(s): John Dillery Source: The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 117, No. 2 (Summer, 1996), pp. 217-254 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1561895 Accessed: 06/09/2010 12:38 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Journal of Philology. -

A Comparison Between Organic and Conventional Olive Farming in Messenia, Greece

horticulturae Article A Comparison between Organic and Conventional Olive Farming in Messenia, Greece Håkan Berg 1,*, Giorgos Maneas 1,2 and Amanda Salguero Engström 1 1 Department of Physical Geography, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (A.S.E.) 2 Navarino Environmental Observatory, Navarino dunes, Costa Navarino, 24 001 Messinia, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +46-702559069 Received: 15 May 2018; Accepted: 4 July 2018; Published: 9 July 2018 Abstract: Olive farming is one of the most important occupations in Messenia, Greece. The region is considered the largest olive producer in the country and it is recognized as a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) for Kalamata olive oil, which is considered extra fine. In response to the declining trend of organic olive farming in Greece, this study assesses to what extent organic olive farming in Messenia provides a financially and environmentally competitive alternative to conventional olive farming. In this study, 39 olive farmers (23 conventional and 16 organic) participated in interviews based on questionnaires. The results showed that organic olive farming is significantly more profitable than conventional farming, primarily because of a higher price for organic olive oil. Despite this, the majority of the conventional farmers perceived a low profit from organic farming as the main constraint to organic olive farming. All farmers agreed that organic olive farming contributed to a better environment, health and quality of olive oil. Organic farmers used fewer synthetic pesticides and fertilizers and applied more environmentally-friendly ground vegetation management techniques than conventional farmers. -

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015 I. Introduction The Board of Directors (“Board”) has requested information relating to facility operations at the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range (“Chabot Gun Range” or “gun range”), including estimated capital and operation and maintenance costs required for continued operation of the gun range. As discussed below, District staff has gathered information regarding environmental compliance, facility conditions and deferred maintenance, sound impacts and mitigation options, and information related to use, revenue, and operational costs of the gun range. II. CEQA Compliance No action by the Board is being requested at this time, and therefore no action is necessary to comply with CEQA for purposes of this Board item. However, a decision by the Board to consider entry into a long term extension of the Chabot Gun Club’s lease would first require environmental review under CEQA, most likely the preparation of an environmental impact report (EIR). III. History of the Chabot Gun Range In 1963, the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range was developed in cooperation with the Oakland Pistol Club, which had previously leased a site in Knowland Park, Oakland, California. The original 1962 lease was a partnership between the District and the Oakland Pistol Club to construct, develop, operate and maintain a marksmanship range in Anthony Chabot Regional Park. In 1964, the original lease was amended to finalize the schedule and define the cost-share for construction of the Chabot Gun Range. In 1967, the District entered into a new long-term lease with Chabot Gun Club, Inc. -

Lot 1 from Krivevac Stables 1 the Property of Mr

LOT 1 FROM KRIVEVAC STABLES 1 THE PROPERTY OF MR. JOHN McLOUGHLIN Danzig Northern Dancer Blue Ocean (USA) Pas de Nom Foreign Courier Sir Ivor BAY FILLY Courtly Dee (IRE) Nomination Dominion February 25th, 2002 Stoneham Girl Rivers Maid (Second Produce) (GB) Persian Tapestry Tap On Wood (1992) Persian Polly E.B.F. nominated. 1st dam STONEHAM GIRL (GB): placed twice at 2 years; also placed once over hurdles; She also has a yearling filly by Wizard King (GB). 2nd dam PERSIAN TAPESTRY: 2 wins and £7,702 at 3 and 5 years inc. Midsomer Norton Handicap, Bath, placed 3 times; dam of 3 winners: Triple Blue (IRE) (c. by Bluebird (USA)): 2 wins and £26,039 at 2 years, 2000, placed 7 times inc. 2nd ABN Amro Futures Ltd Dragon S., Sandown Park, L. 3rd Vodafone Woodcote S., Epsom, L. and City Index Sirenia S., Kempton Park, L. Amra (IRE): 5 wins in Turkey and £127,308 at 2 to 4 years, 2001 and placed 9 times. Need You Badly (GB): winner at 3 years, placed 5 times, broodmare. Spanish Thread (GB): placed once at 2 years, broodmare. Stoneham Girl (GB): see above. Flower Hill Lad (IRE): placed 5 times at 2, 3 and 5 years. She also has a yearling filly by Bluebird (USA) and a colt foal by Bluebird (USA). 3rd dam Persian Polly: winner at 2 years, placed twice inc. 3rd Park S., Leopardstown, Gr.3; dam of 7 winners inc. LAKE CONISTON (IRE), Champion older sprinter in Europe in 1995: 7 wins: 6 wins and £202,278 at 3 and 4 years inc. -

View Provisional Stallions for 2022 Foals

Published here is the Provisional List of the stallions registered with the EBF for the 2021 Covering Season. Prepared by: The European Breeders’ Fund, Lushington House, Full eligibility of each stallion’s progeny, CONCEIVED IN 2021 IN THE NORTHERN HEMISPHERE, (the EBF 119 High Street, Newmarket, Suffolk, CB8 9AE, UK foal crop of 2022), for benefits under the terms and conditions of the EBF, is DEPENDENT UPON RECEIPT INTERNATIONAL OF THE BALANCE OF THE DUE CONTRIBUTION BY 15TH DECEMBER 2021. Late stallion entries for the T: +44 (0) 1638 667960 E: [email protected] EBF will be included in the Final List, provided the full contribution is received by 15th December 2021. www.ebfstallions.com STALLIONS STALLION STANDS ADMIRE MARS (JPN) JPN A C DRAGON PULSE (IRE) GALILEO GOLD (GB) IT’S GINO (GER) MAHSOOB (GB) ORDER OF ST GEORGE (IRE) ROSENSTURM (IRE) SUCCESS DAYS (IRE) WALDPFAD (GER) BRICKS AND MORTAR (USA) JPN ABYDOS (GER) CABLE BAY (IRE) DREAM AHEAD (USA) GALIWAY (GB) IVANHOWE (GER) MAKE BELIEVE (GB) OUTSTRIP (GB) ROSS (IRE) SUMBAL (IRE) WALK IN THE PARK (IRE) CITY OF LIGHT (USA) USA ACCLAMATION (GB) CALYX (GB) DSCHINGIS SECRET (GER) GAMMARTH (FR) IVAWOOD (IRE) MALINAS (GER) P ROYAL LYTHAM (FR) SWISS SPIRIT (GB) WAR COMMAND (USA) DREFONG (USA) JPN ACLAIM (IRE) CAMACHO (GB) DUBAWI (IRE) GAMUT (IRE) J MANATEE (GB) PALAVICINI (USA) RULE OF LAW (USA) T WASHINGTON DC (IRE) DURAMENTE (JPN) JPN ADAAY (IRE) CAMELOT (GB) DUE DILIGENCE (USA) GARSWOOD (GB) JACK HOBBS (GB) MARCEL (IRE) PAPAL BULL (GB) RULER OF THE WORLD (IRE) TAAREEF (USA) WATAR -

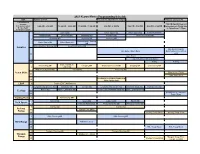

2021 Camp Keowa Master Programming Schedule

2021 Keowa Master Programming Schedule KEY Update: 2/17/21 ←Lunch 12:15pm/Siesta 1:00pm ←Dinner Lineup 5:45 I = instructional program 7:00 PM (Spirit Program) O = open program 9:00 AM - 9:50 AM 10:00 AM - 10:50 AM 11:00 AM - 11:50 AM 2:00 PM - 2:50 PM 3:00 PM - 3:50 PM 4:00 PM - 4:50 PM No program on Friday due B = bookable to Campfire at 7:30pm A = Adult Program BSA Guard Water Sports MB Water Sports MB Instructional Swim Swimming MB Swimming MB Swimming MB Kayaking MB Small Boat Sailing MB Lifesaving MB Kayaking MB Canoeing MB I Motor Boating / Rowing Water Sports MB Water Sports MB MB Aquatics Motor Boating / Rowing MB Small Boat Sailing MB Mile Swim/ Rowing Mile Swim (Thurs Only) Qualifications (Tues/Wed O only) Open Swim Open Boating (ends at 4:30pm) B Tubing Tubing Signs, Signals, & Geocaching MB Camping MB Wilderness Survival MB Camping MB Orienteering MB I Codes MB Wilderness Survival MB First Aid MB Pioneering MB Scout Skills Firem'n Chit (Thurs) O Totin' Chip (Tues) Introduction to Outdoor Leadership A Skills (Adults Only) LEAF I Project LEAF (AM Session) Envionmental Science MB Astronomy MB Forestry MB Environmental Science MB Mammal Study MB Plant Science MB I Ecology Nature MB Space Exploration MB Reptile and Amphibian Study MB Space Exploration MB Introduction to Leave No O Trace (Tues) Trading Post I Salemanship MB Fishing MB Sports MB Athletics MB Sports MB Field Sports I Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB I Archery MB Archery MB Archery O Archery Free Shoot Range B Archery Troop Shoot Archery -

Sage Is , Based Pressure E Final Out- Rned by , : Hearts, Could Persuade

Xerxes' War 137 136 Herodotus Book 7 a match for three Greeks. The same is true of my fellow Spartans. fallen to the naval power of the invader. So the Spartans would have They are the equal of any men when they fight alone; fighting to stood alone, and in their lone stand they would have performed gether, they surpass all other men. For they are free, but not entirely mighty deeds and died nobly. Either that or, seeing the other Greeks free: They obey a master called Law, and they fear this master much going over to the Persians, they would have come to terms with more than your men fear you. They do whatever it commands them Xerxes. Thus, in either case, Greece would have been subjugated by the Persians, for I cannot see what possible use it would have been to to do, and its commands are always the same: Not to retreat from the fortify the Isthmus if the king had had mastery over the sea. battlefield even when badly outnumbered; to stay in formation and either conquer or die. So if anyone were to say that the Athenians were saviors of "If this talk seems like nonsense to you, then let me stay silent Greece, he would not be far off the truth. For it was the Athenians who held the scales in balance; whichever side they espoused would henceforth; I spoke only under compulsion as it is. In any case, sire, I be sure to prevail. It was they who, choosing to maintain the freedom hope all turns out as you wish." of Greece, roused the rest of the Greeks who had not submitted, and [7.105] That was Demaratus' response. -

The 2010 Elections for the Greek Regional Authorities

The 2010 Elections for the Greek Regional Authorities Andreadis I., Chadjipadelis Th. Department of Political Sciences, Aristotle University Thessaloniki Greece Paper for the 61st Political Studies Association Annual Conference "Transforming Politics: New Synergies" 19 - 21 April 2011 London, UK Panel:: “GPSG Panel 3 – Contemporary Challenges: Greece Beyond the Crisis” Draft paper. Please do not quote without the authors' permission. Comments welcome at: [email protected] or [email protected] Copyright PSA 2011 Abstract Τhe recently enacted Greek Law for the new architecture of local and decentralized administration with the code name "Kallikrates" has introduced a number of significant changes for both primary and secondary level institutions of local administration. For instance, the new law includes provisions for the election of Regional Governors by the citizens for the first time in modern Greece. Also, Kallikrates brings back the rule requiring more than 50% of all valid votes for the successful election of a candidate to the public office. Finally, the local elections are held in the middle of the economic crisis. In this article we present a multifaceted analysis of the results of the 2010 Greek regional elections. Some aspects of the analysis are based on evidence obtained by comparing the votes for the regional council candidates with the votes of the 2009 parliamentary elections for the political parties that support these candidates. Further analysis is based on data obtained by voter positions on a series of issues and the analysis of the criteria used by Greek voters for selecting Regional Governors. The article concludes with discussion on how the economic crisis might have affected the voting behaviour of Greek citizens and implications for interested parties. -

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Ancient Greek Philosophy but didn’t Know Who to Ask Edited by Patricia F. O’Grady MEET THE PHILOSOPHERS OF ANCIENT GREECE Dedicated to the memory of Panagiotis, a humble man, who found pleasure when reading about the philosophers of Ancient Greece Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything you always wanted to know about Ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask Edited by PATRICIA F. O’GRADY Flinders University of South Australia © Patricia F. O’Grady 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Patricia F. O’Grady has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identi.ed as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA Ashgate website: http://www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask 1. Philosophy, Ancient 2. Philosophers – Greece 3. Greece – Intellectual life – To 146 B.C. I. O’Grady, Patricia F. 180 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask / Patricia F. -

The Malay Archipelago

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT The Malay Archipelago: the land of the orang-utan, and the bird of paradise; a IN RETROSPECT narrative of travel, with studies of man and nature ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE The Malay Macmillan/Harper Brothers: first published 1869. lfred Russel Wallace was arguably the greatest field biologist of the nine- Archipelago teenth century. He played a leading Apart in the founding of both evolutionary theory and biogeography (see page 162). David Quammen re-enters the ‘Milky Way of He was also, at times, a fine writer. The best land masses’ evoked by Alfred Russel Wallace’s of his literary side is on show in his 1869 classic, The Malay Archipelago, a wondrous masterpiece of biogeography. book of travel and adventure that wears its deeper significance lightly. The Malay Archipelago is the vast chain of islands stretching eastward from Sumatra for more than 6,000 kilometres. Most of it now falls within the sovereignties of Malaysia and Indonesia. In Wallace’s time, it was a world apart, a great Milky Way of land masses and seas and straits, little explored by Europeans, sparsely populated by peoples of diverse cul- tures, and harbouring countless species of unknown plant and animal in dense tropical forests. Some parts, such as the Aru group “Wallace paid of islands, just off the his expenses coast of New Guinea, by selling ERNST MAYR LIB., MUS. COMPARATIVE ZOOLOGY, HARVARD UNIV. HARVARD ZOOLOGY, LIB., MUS. COMPARATIVE MAYR ERNST were almost legend- specimens. So ary for their remote- he collected ness and biological series, not just riches. Wallace’s jour- samples.” neys throughout this region, sometimes by mail packet ship, some- times in a trading vessel or a small outrigger canoe, were driven by a purpose: to collect animal specimens that might help to answer a scientific question. -

Bearing Razors and Swords: Paracomedy in Euripides’ Orestes

%HDULQJ5D]RUVDQG6ZRUGV3DUDFRPHG\LQ(XULSLGHV· 2UHVWHV &UDLJ-HQG]D $PHULFDQ-RXUQDORI3KLORORJ\9ROXPH1XPEHU :KROH1XPEHU )DOOSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV '2, KWWSVGRLRUJDMS )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by University of Kansas Libraries (5 Dec 2016 18:13 GMT) BEARING RAZORS AND SWORDS: PARACOMEDY IN EURIPIDES’ ORESTES CRAIG JENDZA Abstract. In this article, I trace a nuanced interchange between Euripides’ Helen, Aristophanes’ Thesmophoriazusae, and Euripides’ Orestes that contains a previ- ously overlooked example of Aristophanic paratragedy and Euripides’ paracomic response. I argue that the escape plot from Helen, in which Menelaus and Helen flee with “sword-bearing” men ξιφηφόρος( ), was co-opted in Thesmophoriazusae, when Aristophanes staged Euripides escaping with a man described as “being a razor-bearer” (ξυροφορέω). Furthermore, I suggest that Euripides re-appropriates this parody by escalating the quantity of sword-bearing men in Orestes, suggest- ing a dynamic poetic rivalry between Aristophanes and Euripides. Additionally, I delineate a methodology for evaluating instances of paracomedy. PARATRAGEDY, COMEDY’S AppROPRIATION OF LINES, SCENES, AND DRAMATURGY FROM TRAGEDY, constitutes a source of the genre’s authority (Foley 1988; Platter 2007), a source of the genre’s identity as a literary underdog in comparison to tragedy (Rosen 2005), and a source of its humor either through subverting or ridiculing tragedy (Silk 1993; Robson 2009, 108–13) or through audience detection and identification of quotations (Wright 2012, 145–50).1 The converse relationship between 1 Rau 1967 marks the beginning of serious investigation into paratragedy by analyz- ing numerous comic scenes that are modeled on tragic ones and providing a database, with hundreds of examples, of tragic lines that Aristophanes parodies.