Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toys for the Collector

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Toys for the Collector Tuesday 10th March 2020 at 10.00 PLEASE NOTE OUR NEW ADDRESS Viewing: Monday 9th March 2020 10:00 - 16:00 9:00 morning of auction Otherwise by Appointment Special Auction Services Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL (Sat Nav tip - behind SPX Flow RG14 5TR) Dave Kemp Bob Leggett Telephone: 01635 580595 Fine Diecasts Toys, Trains & Figures Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Dominic Foster Graham Bilbe Adrian Little Toys Trains Figures Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price Order of Auction 1-173 Various Die-cast Vehicles 174-300 Toys including Kits, Computer Games, Star Wars, Tinplate, Boxed Games, Subbuteo, Meccano & other Construction Toys, Robots, Books & Trade Cards 301-413 OO/ HO Model Trains 414-426 N Gauge Model Trains 427-441 More OO/ HO Model Trains 442-458 Railway Collectables 459-507 O Gauge & Larger Models 508-578 Diecast Aircraft, Large Aviation & Marine Model Kits & other Large Models Lot 221 2 www.specialauctionservices.com Various Diecast Vehicles 4. Corgi Aviation Archive, 7. Corgi Aviation Archive a boxed group of eight 1:72 scale Frontier Airliners, a boxed group of 1. -

Meeting the Challenge of Maritime Security

Meeting the Challenge Of MaritiMe Security A Publication Of Second1 Line Of Defense ForewOrd Meeting the Challenge Of MaritiMe SeCurity he interviews and essays in this booklet have appeared in earlier Section One: The Challenges versions on the web site Second Line of Defense (http://www.sldinfo. The Challenge of Risk Management 5 com/). SLDinfo.com focuses on the creation and sustainment of Protecting the Global Conveyer Belt 7 military and security capability and the crucial role of the support European Naval Force: A Promising “First” 9 community (logistics community, industrial players, civilian contractors, etc.) along with evolving public-private partnerships Section Two: Shaping an Effective Tool Set t among democracies and partners in crafting real military and security Building Maritime Security Tools for the Global Customer 12 capabilities. On SLDinfo.com, articles, videos and photo slideshows on military and Maritime Safety and Security: Going the Extra Mile 15 security issues are posted on a weekly basis. Building a 21st Century Port: The Core Role of Security 18 The Role of C4ISR in the U.S. Coast Guard 21 Some of the articles and interviews in Meeting the Challenge of Maritime Security are Shaping a 21st Century U.S. Coast Guard: The Key Role for Maritime Patrol Aircraft 23 excerpted from the longer pieces on SLDinfo.com, as indicated at the beginning of the Miami Air Station: USCG and Caribbean Maritime Security 25 article. The original pieces on the web site often include photos and graphics which are Building the Ocean Sentry ..62 6.52 27 not included in this publication. -

Aviation Classics Magazine

Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 taxies towards the camera in impressive style with a haze of hot exhaust fumes trailing behind it. Luigino Caliaro Contents 6 Delta delight! 8 Vulcan – the Roman god of fire and destruction! 10 Delta Design 12 Delta Aerodynamics 20 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan 62 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.6 Nos.1 and 2 64 RAF Scampton – The Vulcan Years 22 The ‘Baby Vulcans’ 70 Delta over the Ocean 26 The True Delta Ladies 72 Rolling! 32 Fifty years of ’558 74 Inside the Vulcan 40 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.3 78 XM594 delivery diary 42 Vulcan display 86 National Cold War Exhibition 49 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.4 88 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.7 52 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.5 90 The Council Skip! 53 Skybolt 94 Vulcan Furnace 54 From wood and fabric to the V-bomber 98 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.8 4 aviationclassics.co.uk Left: Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 caught in some atmospheric lighting. Cover: XH558 banked to starboard above the clouds. Both John M Dibbs/Plane Picture Company Editor: Jarrod Cotter [email protected] Publisher: Dan Savage Contributors: Gary R Brown, Rick Coney, Luigino Caliaro, Martyn Chorlton, Juanita Franzi, Howard Heeley, Robert Owen, François Prins, JA ‘Robby’ Robinson, Clive Rowley. Designers: Charlotte Pearson, Justin Blackamore Reprographics: Michael Baumber Production manager: Craig Lamb [email protected] Divisional advertising manager: Tracey Glover-Brown [email protected] Advertising sales executive: Jamie Moulson [email protected] 01507 529465 Magazine sales manager: -

Price List of MALDIVES 23 07 2020

MALDIVES 23 07 2020 - Code: MLD200101a-MLD200115b Newsletter No. 1284 / Issues date: 23.07.2020 Printed: 25.09.2021 / 05:10 Code Country / Name Type EUR/1 Qty TOTAL Stamperija: MLD200101a MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €4.00 - - Y&T: 7398-7401 Mushrooms (Mushrooms (Coprinus comatus; FDC €6.50 - - Michel: 9135-9138 Morchella esculenta; Leccinum aurantiacum; Amanita Imperforated €15.00 - - pantherina)) FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200101b MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €3.00 - - Y&T: 1455 Mushrooms (Mushrooms (Gyromitra esculenta) FDC €5.50 - - Michel: 9139 / Bl.1485 Background info: Boletus edulis) Imperforated €15.00 - - FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200102a MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €4.50 - - Y&T: 7402-7405 Dinosaurs (Dinosaurs (Dilophosaurus wetherilli; FDC €7.00 - - Michel: 9150-9153 Tyrannosaurus rex; Stegosaurus stenops; Imperforated €15.00 - - Parasaurolophus walkeri)) FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200102b MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €3.50 - - Y&T: 1456 Dinosaurs (Dinosaurs (Triceratops horridus) FDC €6.00 - - Michel: 9154 / Bl.1488 Background info: Tyrannosaurus rex; Parasaurolophus Imperforated €15.00 - - walkeri) FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200103a MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €4.00 - - Shells (Shells (Turbo jourdani; Pecten vogdesi; Conus FDC €6.50 - - omaria; Tutufa bubo)) Imperforated €15.00 - - FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: MLD200103b MALDIVES 2020 Perforated €3.00 - - Y&T: 1457 Shells (Shells (Pseudozonaria annettae) Background FDC €5.50 - - Michel: 9144 / Bl.1486 info: Murex pecten; Vokesimurex dentifer; -

1 P247 Musketry Regulations, Part II RECORDS' IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference Number

P247 Musketry Regulations, Part II RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: GB1741/P247 Alternative reference number: Title: Musketry Regulations, Part II Dates of creation: 1910 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 1 volume Format: Paper RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: The War Office Administrative history: The War Office was a department of the British Government, responsible for the administration of the British Army between the 17th century and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the Ministry of Defence. The name "War Office" is also often given to the former home of the department, the Old War Office Building on Horse Guards Avenue, London. The War Office declined greatly in importance after the First World War, a fact illustrated by the drastic reductions in its staff numbers during the inter-war period. On 1 April 1920, it employed 7,434 civilian staff; this had shrunk to 3,872 by 1 April 1930. Its responsibilities and funding were also reduced. In 1936, the government of Stanley Baldwin appointed a Minister for Co-ordination of Defence, who worked outside of the War Office. When Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940, he bypassed the War Office altogether and appointed himself Minister of Defence (though there was, curiously, no ministry of defence until 1947). Clement Attlee continued this arrangement when he came to power in 1945 but appointed a separate Minister of Defence for the first time in 1947. In 1964, the present form of the Ministry of Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archives 1 Defence was established, unifying the War Office, Admiralty, and Air Ministry. -

Freeman's Folly

Chapter 9 Freeman’s Folly: The Debate over the Development of the “Unarmed Bomber” and the Genesis of the de Havilland Mosquito, 1935–1940 Sebastian Cox The de Havilland Mosquito is, justifiably, considered one of the most famous and effective military aircraft of the Second World War. The Mosquito’s devel- opment is usually portrayed as being a story of a determined and independent aircraft company producing a revolutionary design with very little input com- ing from the official Royal Air Force design and development process, which normally involved extensive consultation between the Air Ministry’s technical staff and the aircraft’s manufacturer, culminating in an official specification being issued and a prototype built. Instead, so the story goes, de Havilland’s design team thought up the concept of the “unarmed speed bomber” all by themselves and, despite facing determined opposition from the Air Ministry and the raf, got it adopted by persuading one important and influential senior officer, Wilfrid Freeman, to put it into production (Illustration 9.1).1 Thus, before it proved itself in actuality a world-beating design, it was known in the Ministry as “Freeman’s Folly”. Significantly, even the UK Official History on the “Design and Development of Weapons”, published in 1964, perpetuated this explanation, stating that: When … [de Havilland] found itself at the beginning of the war short of orders and anxious to contribute to the war effort they proceeded to design an aeroplane without any official prompting from the Air Minis- try. They had to think out for themselves the whole tactical and strategic purpose of the aircraft, and thus made a number of strategic and tactical assumptions which were not those of the Air Staff. -

Vintage Or Classic

Dates for the Diary 2012 June 16-17th Vintage Parasol Pietenpol Club and Bicester Weekend VAC 30th International Rally VAC Bembridge www.vintageaircraftclub.org.ukwww.vintageaircraftclub.org.uk IssueIssue 3838 SummerSummer 20122012 July 1st International Rally VAC Bembridge August 4th-5th Stoke Golding Stake SG Stoke Golding Out 11th-12th International Luscombe Oaksey Park Luscombe Rally 18th-19th International Moth dHMC Belvoir Castle Rally 18th-19th Sywell Airshow and Sywell Sywell Vintage Fly-In 31st LAA Rally LAA Sywell September 1st - 2nd LAA Rally LAA Sywell October 6th / 7th MEMBERS ONLY EVENT 13th VAC AGM VAC Bicester 28th All Hallows Rally VAC Leicester Dates for the Diary 2013 January 20th Snowball Social VAC Sywell February 10th Valentine Social VAC TBA VA C March 9th Annual Dinner VAC Littlebury, Bicester Spring Rally Turweston VAC April 13th Daffodil Rally VAC Fenland The Vintage Aircraft Club Ltd (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Registered Address: Winter Hills Farm, Silverstone, Northants, NN12 8UG Registered in England No 2492432 The Journal of the Vintage Aircraft Club VAC Honorary President D.F.Ogilvy. OBE FRAeS Chairman’s Notes Vintage & Classic ne recent comment summed it up perfectly. “If this Pietenpol builders. The tenth share, which has been given VAC Committee drought goes on much longer, I’ll have to buy some by John to the UK Pietenpol Club and is held in Trust by O new wellies!” the Chairman, will each year be offered to a suitable Chairman Steve Slater 01494-776831 Summer 2012 recipient, who pays a proportion of running and insurance [email protected] Hopefully, by the time you read this, the winds will have costs in return for being allowed to fly the aeroplane. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm). -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

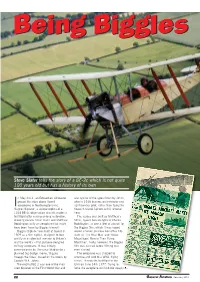

Being Biggles Biggles

BeingBeing Biggles Biggles Steve Slater tells the story of a BE-2c which is not quite 100 years old but has a history of its own n May 2011, an Edwardian silhouette was typical of the types flown by Johns, graced the skies above Sywell who in 1918 became an instructor and Iaerodrome in Northamptonshire. light bomber pilot, rather than flying the ‘Biggles Biplane’, a unique replica of a Sopwith Camel fighters of his fictional 1914 BE-2c observation aircraft, made its hero. first flight after a six-year-long restoration, The replica was built by Matthew’s allowing owners Steve Slater and Matthew father, Sywell-based engineer Charles Boddington to fly an aeroplane that might Boddington, as one a fleet of aircraft for have been flown by Biggles himself. the Biggles film, which it was hoped ‘Biggles Biplane’ was built at Sywell in would emulate previous box office hits 1969 as a film replica, designed to look such as ‘The Blue Max’ and ‘Those and fly in an identical manner to Britain’s – Magnificent Men in Their Flying and the world’s – first purpose-designed Machines’. Sadly, however, the Biggles military aeroplane. It was initially film was canned before filming was commissioned by Universal Studios for a even started. planned big-budget movie, ‘Biggles The aeroplane was shipped to Sweeps the Skies’, based on the books by America and sold to a WW1 ‘flying Captain W.E. Johns. circus’. It made its last flight in the The original BE-2 was one of the most- USA on June 14th 1977. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Battleships and Dividends: The Rise of Private Armaments Firms in Great Britain and Italy, c. 1860-1914 MARCHISIO, GIULIO How to cite: MARCHISIO, GIULIO (2012) Battleships and Dividends: The Rise of Private Armaments Firms in Great Britain and Italy, c. 1860-1914, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7323/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Battleships and Dividends: The Rise of Private Armaments Firms in Great Britain and Italy, c. 1860-1914 Giulio Marchisio This thesis analyses the rise of private armaments firms in Great Britain and in Italy from mid-19th century to the outbreak of the First World War, with a focus on naval armaments and military shipbuilding. During this period, the armaments industry underwent a radical transformation, moving from being based on public-owned arsenals and yards to being based on private firms – the system of military procurement prevalent today. -

Naval Ensigns & Jacks

INTERNATIONAL TREASURES ™ A NATIONAL TREASURE Naval Ensigns & Jacks ZFC3577 USSR, Cruiser Aurora, unique, Order of the Oct. Revolution & Military Order of the Red Banner, Holiday Ensign, 1992. This variant of the Soviet Naval Ensign is from the Cruiser Aurora, a ship with a long and distinguished career. The Aurora is an armored cruiser currently preserved and serving as a school and museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia. ZFC0228 Lead Royal Navy ship, D-Day Operation Overlord, ZFC0514 France Ensign, FFL Aconite WWII, Sank 2 German Invasion of Normandy, 1944. This battle ensign was on the leading U-Boats on same day, 1943. An iconic French ensign which embod Royal Navy ship of the invasion that assaulted the Normandy ies the brief, yet brave, struggle of French forces against fascist beaches on June 6, 1944. Commander Anthony Kimmins secured Germany in the opening years of WWII. This flag comes from the the flag for Calvin Bullock for his return visit to New York. FNFL corvette ‘Aconite’ and was part of the Bullock Collection. ZFC0232 Royal Canadian Navy White Ensign, HMCS Wetaskiwin, ZFC0503 Lead Royal Navy ship Eastern Tack Force, Operation “Battle of the Atlantic,” 1943. This White Ensign, according to Husky, Invasion of Sicily, 1943. Due to wartime security constraints, Calvin Bullock’s documentation was “From His Majesty’s Canadian the name of the vessel that wore this ensign remains unknown. The Corvette WETASKIWIN, which for long had been flown in both the documentation states only that it flew on the task force leading the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.” allied attacks on Sicily.