Gray Proof-Amended

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovative Approaches to Melodic Elaboration in Contemporary Tabuh Kreasibaru

INNOVATIVE APPROACHES TO MELODIC ELABORATION IN CONTEMPORARY TABUH KREASIBARU by PETER MICHAEL STEELE B.A., Pitzer College, 2003 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2007 © Peter Michael Steele, 2007 ABSTRACT The following thesis has two goals. The first is to present a comparison of recent theories of Balinese music, specifically with regard to techniques of melodic elaboration. By comparing the work of Wayan Rai, Made Bandem, Wayne Vitale, and Michael Tenzer, I will investigate how various scholars choose to conceptualize melodic elaboration in modern genres of Balinese gamelan. The second goal is to illustrate the varying degrees to which contemporary composers in the form known as Tabuh Kreasi are expanding this musical vocabulary. In particular I will examine their innovative approaches to melodic elaboration. Analysis of several examples will illustrate how some composers utilize and distort standard compositional techniques in an effort to challenge listeners' expectations while still adhering to indigenous concepts of balance and flow. The discussion is preceded by a critical reevaluation of the function and application of the western musicological terms polyphony and heterophony. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents : iii List of Tables .... '. iv List of Figures ' v Acknowledgements vi CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Methodology • • • • • :•-1 Background : 1 Analysis: Some Recent Thoughts 4 CHAPTER 2 Many or just Different?: A Lesson in Categorical Cacophony 11 Polyphony Now and Then 12 Heterophony... what is it, exactly? 17 CHAPTER 3 Historical and Theoretical Contexts 20 Introduction 20 Melodic Elaboration in History, Theory and Process ..' 22 Abstraction and Elaboration 32 Elaboration Types 36 Constructing Elaborations 44 Issues of "Feeling". -

![Liner Notes to “Bali 1928: Gamelan Gong Kebyar.” World Arbiter 2011 [CD]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0732/liner-notes-to-bali-1928-gamelan-gong-kebyar-world-arbiter-2011-cd-90732.webp)

Liner Notes to “Bali 1928: Gamelan Gong Kebyar.” World Arbiter 2011 [CD]

CMYK 80785-2 80785-2 WAYNE VITALE & BRIAN BAUMBUSCH (b. 1956) (b. 1987) WAYNE VITALE &WAYNE BRIAN BAUMBUSCH MIKROKOSMA File Under: Classical/ Contemporary/ Vitale–Baumbusch NEW WORLD RECORDS Mikrokosma (2014–15) 51:55 8. VIII. Gineman Out 5:37 (Wayne Vitale & Brian Baumbusch) 9. IX. Pomp Out 3:58 1. I. Feet 1:28 10. X. Selunding Out 3:31 2. II. Selunding 6:28 11. XI. Feet Out 2:45 3. III. Pomp 7:10 The Lightbulb Ensemble, Brian Baumbusch, musical director 4. IV. Gineman 5:23 • MIKROKOSMA 5. V. Dance 3:35 12. Ellipses (2015) 9:27 6. VI. Pencon 8:32 (Brian Baumbusch) Santa Cruz Contemporary Gamelan, 7. VII. Tari 3:28 Brian Baumbusch, musical director TT: 61:31 • MIKROKOSMA NEW WORLD RECORDS New World Records, 20 Jay Street, Suite 1001,Brooklyn, NY112 01 Tel (212) 290-1680 Fax (646) 224-9638 WAYNE VITALE &WAYNE BRIAN BAUMBUSCH [email protected] www.newworldrecords.org ൿ & © 2017 Anthology of Recorded Music, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. 80785-2 80785-2 CMYK WAYNE VITALE & BRIAN BAUMBUSCH (b. 1956) (b. 1987) MIKROKOSMA WAYNEWAYNE VITALEVITALE&& BRIANBRIAN BAUMBUSCHBAUMBUSCH Mikrokosma (2014–15) 51:55 (Wayne Vitale & Brian Baumbusch) MIKROKOSMA 1. I. Feet 1:28 2. II. Selunding 6:28 3. III. Pomp 7:10 4. IV. Gineman 5:23 5. V. Dance 3:35 6. VI. Pencon 8:32 7. VII. Tari 3:28 8. VIII. Gineman Out 5:37 9. IX. Pomp Out 3:58 10. X. Selunding Out 3:31 11. XI. Feet Out 2:45 The Lightbulb Ensemble, Brian Baumbusch, musical director 12. -

Sòouünd Póetry the Wages of Syntax

SòouÜnd Póetry The Wages of Syntax Monday April 9 - Saturday April 14, 2018 ODC Theater · 3153 17th St. San Francisco, CA WELCOME TO HOTEL BELLEVUE SAN LORENZO Hotel Spa Bellevue San Lorenzo, directly on Lago di Garda in the Northern Italian Alps, is the ideal four-star lodging from which to explore the art of Futurism. The grounds are filled with cypress, laurel and myrtle trees appreciated by Lawrence and Goethe. Visit the Mart Museum in nearby Rovareto, designed by Mario Botta, housing the rich archive of sound poet and painter Fortunato Depero plus innumerable works by other leaders of that influential movement. And don’t miss the nearby palatial home of eccentric writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. The hotel is filled with contemporary art and houses a large library https://www.bellevue-sanlorenzo.it/ of contemporary art publications. Enjoy full spa facilities and elegant meals overlooking picturesque Lake Garda, on private grounds brimming with contemporary sculpture. WElcome to A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC The 23rd Other Minds Festival is presented by Other Minds in 2 Message from the Artistic Director association with ODC Theater, 7 What is Sound Poetry? San Francisco. 8 Gala Opening All Festival concerts take place at April 9, Monday ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., San Francisco, CA at Shotwell St. and 12 No Poets Don’t Own Words begin at 7:30 PM, with the exception April 10, Tuesday of the lecture and workshop on 14 The History Channel Tuesday. Other Minds thanks the April 11, Wednesday team at ODC for their help and hard work on our behalf. -

Performance in Bali

Performance in Bali Performance in Bali brings to the attention of students and practitioners in the twenty-first century a dynamic performance tradition that has fasci- nated observers for generations. Leon Rubin and I Nyoman Sedana, both international theatre professionals as well as scholars, collaborate to give an understanding of performance culture in Bali from inside and out. The book describes four specific forms of contemporary performance that are unique to Bali: • Wayang shadow-puppet theatre • Sanghyang ritual trance performance • Gambuh classical dance-drama • the virtuoso art of Topeng masked theatre. The book is a guide to current practice, with detailed analyses of recent theatrical performances looking at all aspects of performance, production and reception. There is a focus on the examination and description of the actual techniques used in the training of performers, and how some of these techniques can be applied to Western training in drama and dance. The book also explores the relationship between improvisation and rigid dramatic structure, and the changing relationships between contemporary approaches to performance and traditional heritage. These culturally unique and beautiful theatrical events are contextualised within religious, intel- lectual and social backgrounds to give unparalleled insight into the mind and world of the Balinese performer. Leon Rubin is Director of East 15 Acting School, University of Essex. I Nyoman Sedana is Professor at the Indonesian Arts Institute (ISI) in Bali, Indonesia. Contents List -

Other Minds 19 Official Program

SFJAZZ CENTER SFJAZZ MINDS OTHER OTHER 19 MARCH 1ST, 2014 1ST, MARCH A FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 28 FEBRUARY OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC Find Left of the Dial in print or online at sfbg.com WELCOME A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED TO OTHER MINDS 19 NEW MUSIC The 19th Other Minds Festival is 2 Message from the Executive & Artistic Director presented by Other Minds in association 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and SFJazz Center 11 Opening Night Gala 13 Concert 1 All festival concerts take place in Robert N. Miner Auditorium in the new SFJAZZ Center. 14 Concert 1 Program Notes Congratulations to Randall Kline and SFJAZZ 17 Concert 2 on the successful launch of their new home 19 Concert 2 Program Notes venue. This year, for the fi rst time, the Other Minds Festival focuses exclusively on compos- 20 Other Minds 18 Performers ers from Northern California. 26 Other Minds 18 Composers 35 About Other Minds 36 Festival Supporters 40 About The Festival This booklet © 2014 Other Minds. All rights reserved. Thanks to Adah Bakalinsky for underwriting the printing of our OM 19 program booklet. MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WELCOME TO OTHER MINDS 19 Ever since the dawn of “modern music” in the U.S., the San Francisco Bay Area has been a leading force in exploring new territory. In 1914 it was Henry Cowell leading the way with his tone clusters and strumming directly on the strings of the concert grand, then his students Lou Harrison and John Cage in the 30s with their percussion revolution, and the protégés of Robert Erickson in the Fifties with their focus on graphic scores and improvisation, and the SF Tape Music Center’s live electronic pioneers Subotnick, Oliveros, Sender, and others in the Sixties, alongside Terry Riley, Steve Reich and La Monte Young and their new minimalism. -

Merging Bali, India, and the West Through Modernism Une Fusion Parmi D’Autres : Réunir Bali, L’Inde Et L’Occident À Travers Le Modernisme Michael Tenzer

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 15:43 Circuit Musiques contemporaines One Fusion Among Many: Merging Bali, India, and the West through Modernism Une fusion parmi d’autres : réunir Bali, l’Inde et l’Occident à travers le modernisme Michael Tenzer Musiciens sans frontières Résumé de l'article Volume 21, numéro 2, 2011 Le rapport entre les traditions musicales du monde et la musique de concert moderniste de tradition européenne est souvent exploré dans des fusions URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005274ar musicales proposées par des compositeurs, mais les motivations et les DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1005274ar esthétiques de ces oeuvres reçoivent souvent moins d’attention que celles qui s’imprègnent d’approches postmodernes (qu’elles soient minimalistes ou Aller au sommaire du numéro d’affiliation populaire). Dans cet article, l’auteur affirme un rapport entre certaines techniques rigoureuses de la musique contemporaine occidentale et les organisations cycliques, très rationnelles, de la musique indonésienne et indienne. Il poursuit avec une analyse de Unstable Centre/Puser Belah (2003), Éditeur(s) une oeuvre que l’auteur a composée pour deux orchestres gamelan simultanés. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal L’analyse démontre une fusion sur les plans du cycle et de la structure, mais l’article se termine par une évaluation autocrique du projet. ISSN 1183-1693 (imprimé) 1488-9692 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Tenzer, M. (2011). One Fusion Among Many: Merging Bali, India, and the West through Modernism. Circuit, 21(2), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005274ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

Passacaglia PRINT

On Shifting Grounds: Meandering, Modulating, and Möbius Passacaglias David Feurzeig Passacaglias challenge a prevailing assumption underlying traditional tonal analysis: that tonal motion proceeds along a unidirectional “arrow of time.” The term “continuous variation,” which describes characteristic passacaglia technique in contrast to sectional “Theme and Variations” movements, suggests as much: the musical impetus continues forward even as the underlying progression circles back to its starting point. A passacaglia describes a kind of loop. 1 But the loop of a traditional passacaglia is a rather flattened one, ovoid rather than circular. For most of the pattern, the tonal motion proceeds in one direction—from tonic to dominant—then quickly drops back to the tonic, like a skier going gradually up and rapidly down a slope. The looping may be smoother in tonic-requiring passacaglia themes (those which end on the dominant) than in tonic- providing themes, as the dominant harmony propels the music across the “seam” between successive statements of the harmonic pattern. But in both types, a clear dominant-tonic cadence tends to work against a sense of seamless circularity. This is not the case for some more recent passacaglias. A modern compositional type, which to my knowledge has not been discussed before as such, is the modulatory passacaglia.2 Modulating passacaglia themes subvert tonal closure via progressions which employ elements of traditional tonality but veer away from the putative tonal center. Passacaglias built on these themes may take on a more truly circular form, with no obvious start or endpoint. This structural ambiguity is foreshadowed in some Baroque ground-bass compositions. -

Tenzer, Michael

JMM – The Journal of Music and Meaning, vol.2, 2004, section 10 – printout. Original article URL: http://www.musicandmeaning.net/issues/showArticle.php?artID=2.10 [Refer to this article by section numbers, not by page number] JMM Book Review: Tenzer, Michael. Gamelan Gong Kebyar: the Art of Twentieth-Century Balinese Music. Chicago and London: the University of Chicago Press, 2000. xxv, 492 pp., analytic illustrations, transcriptions, photographs, glossary, bibliography, index, two compact discs with musical examples cued to the text. (Reviewed by Edward Green) 10.1 Ethnomusicological Syncretism In this innovative, carefully reasoned book, Michael Tenzer provides a comprehensive, technical account of modern Balinese music. Surprisingly, he approaches the task in a boldly syncretic manner, making coordinated use of indigenous Balinese musical concepts as well as Western analytic tools, such as the mathematics of “contour classes.” In chapter 9 we see Tenzer’s syncretism in full force as he compares, for the purpose of mutual illumination, a blues by Jackie Byard and Wayan Sinti’s important l982 gamelan composition Wilet Mayura. He also makes use of passages by Mozart, Ives and Lutoslawski. Many ethnomusicologists would, on methodological grounds, object to such syncretism, asserting that music can only be understood from “within” a culture, and that any use of theoretical concepts arising from an “outside” culture can only distort. Tenzer plainly disagrees. “The politics of irreducible difference,” he writes in Chapter 10, “continues to -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE JAVANESE WAYANG KULIT PERFORMED IN THE CLASSIC PALACE STYLE: AN ANALYSIS OF RAMA’S CROWN AS TOLD BY KI PURBO ASMORO A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By GUAN YU, LAM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 JAVANESE WAYANG KULIT PERFORMED IN THE CLASSIC PALACE STYLE: AN ANALYSIS OF RAMA’S CROWN AS TOLD BY KI PURBO ASMORO A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. Paula Conlon, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Eugene Enrico ______________________________ Dr. Marvin Lamb © Copyright by GUAN YU, LAM 2016 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would like to take this opportunity to thank the members of my committee: Dr. Paula Conlon, Dr. Eugene Enrico, and Dr. Marvin Lamb for their guidance and suggestions in the preparation of this thesis. I would especially like to thank Dr. Paula Conlon, who served as chair of the committee, for the many hours of reading, editing, and encouragement. I would also like to thank Wong Fei Yang, Thow Xin Wei, and Agustinus Handi for selflessly sharing their knowledge and helping to guide me as I prepared this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their continued support throughout this process. iv Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................... -

Lelambatan in Banjar Wani, Karambitan, Bali

ABSTRACT Title of thesis: LELAMBATAN IN BANJAR WANI, KARAMBITAN, BALI Rachel R. Muehrer, Master of Arts, 2006 Thesis directed by: Professor Jonathan Dueck Department of Music Division of Musicology and Ethnomusicology The ceremonial mus ic genre lelambatan originated from the gamelan gong gede orchestras in the courts of Bali. The once luxurious gamelan gong gede , funded by the rajas , has long departed since Dutch colonization, democratization, and Indonesian independence. Today the musi c is still played for ritual occasions, but in a new context. Gamelan gong kebyar instruments, melted down and rebuilt from those of the gong gede and handed down to the villages from the courts, are utilized in lelambatan because of their versatility and popularity of the new kebyar musical style. The result is remarkable: music from the court system that represents the lavishness of the rajas is played with reverence by the common class on gamelans literally recast to accommodate an egalitarian environm ent. A case study in Karambitan, Bali, examines the lelambatan music that has survived despite, or perhaps with the assistance of, history and cultural policy. LELAMBATAN IN BANJAR WANI, KARAMBITAN, BALI by Rachel R. Muehrer The sis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2006 Advisory Committee: Professor Jonathan Dueck, Chair Professor Ro bert Provine Professor Carolina Robertson Dedication I would like to dedicate this work to my teacher and friend, I Nyoman Suadin – you have touched the lives of more people than you will ever know. -

Society for Ethnomusicology Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology Abstracts Musicianship in Exile: Afghan Refugee Musicians in Finland Facets of the Film Score: Synergy, Psyche, and Studio Lari Aaltonen, University of Tampere Jessica Abbazio, University of Maryland, College Park My presentation deals with the professional Afghan refugee musicians in The study of film music is an emerging area of research in ethnomusicology. Finland. As a displaced music culture, the music of these refugees Seminal publications by Gorbman (1987) and others present the Hollywood immediately raises questions of diaspora and the changes of cultural and film score as narrator, the primary conveyance of the message in the filmic professional identity. I argue that the concepts of displacement and forced image. The synergistic relationship between film and image communicates a migration could function as a key to understanding musicianship on a wider meaning to the viewer that is unintelligible when one element is taken scale. Adelaida Reyes (1999) discusses similar ideas in her book Songs of the without the other. This panel seeks to enrich ethnomusicology by broadening Caged, Songs of the Free. Music and the Vietnamese Refugee Experience. By perspectives on film music in an exploration of films of four diverse types. interacting and conducting interviews with Afghan musicians in Finland, I Existing on a continuum of concrete to abstract, these papers evaluate the have been researching the change of the lives of these music professionals. communicative role of music in relation to filmic image. The first paper The change takes place in a musical environment which is if not hostile, at presents iconic Hollywood Western films from the studio era, assessing the least unresponsive towards their music culture. -

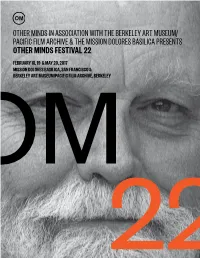

Other Minds in Association with the Berkeley Art

OTHER MINDS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/ PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE & THE MISSION DOLORES BASILICA PRESENTS OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL 22 FEBRUARY 18, 19 & MAY 20, 2017 MISSION DOLORES BASILICA, SAN FRANCISCO & BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE, BERKELEY 2 O WELCOME FESTIVAL TO OTHER MINDS 22 OF NEW MUSIC The 22nd Other Minds Festival is present- 4 Message from the Artistic Director ed by Other Minds in association with the 8 Lou Harrison Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive & the Mission Dolores Basilica 9 In the Composer’s Words 10 Isang Yun 11 Isang Yun on Composition 12 Concert 1 15 Featured Artists 23 Film Presentation 24 Concert 2 29 Featured Artists 35 Timeline of the Life of Lou Harrison 38 Other Minds Staff Bios 41 About the Festival 42 Festival Supporters: A Gathering of Other Minds 46 About Other Minds This booklet © 2017 Other Minds, All rights reserved 3 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR WELCOME TO A SPECIAL EDITION OF THE OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL— A TRIBUTE TO ONE OF THE MOST GIFTED AND INSPIRING FIGURES IN THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN CLASSICAL MUSIC, LOU HARRISON. This is Harrison’s centennial year—he was born May 14, 1917—and in addition to our own concerts of his music, we have launched a website detailing all the other Harrison fêtes scheduled in his hon- or. We’re pleased to say that there will be many opportunities to hear his music live this year, and you can find them all at otherminds.org/lou100/. Visit there also to find our curated compendium of Internet links to his work online, photographs, videos, films and recordings.