Blood Meridian As a Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Army Regulars on the Western Frontier, 1848-1861 / Dunvood Ball

Amy Regulars on the WestmFrontieq r 848-1 861 This page intentionally left blank Army Regulars on the Western Frontier DURWOOD BALL University of Oklahoma Press :Norman Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ball, Dunvood, 1960- Army regulars on the western frontier, 1848-1861 / Dunvood Ball. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8061-3312-0 I. West (U.S.)-History, Military-I 9th century. 2. United States. Army-History- 19th century. 3. United States-Military policy-19th century. 4. Frontier and pioneer life-West (U.S.) 5. West (US.)-Race relations. 6. Indians of North Arnerica- Government relations-1789-1869. 7. Indians of North America-West (U.S.)- History-19th century. 8. Civil-military relations-West (U.S.)-History-19th century. 9. Violence-West (U.S.)-History-I 9th century. I. Title. F593 .B18 2001 3 5~'.00978'09034-dcz I 00-047669 CIP The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources, Inc. m Copyright O 2001 by the University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Publishing Division of the University. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the U.S.A. 12345678910 For Mom, Dad, and Kristina This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Maps IX Preface XI Acknowledgments xv INT R o D U C T I o N : Organize, Deploy, and Multiply XIX Prologue 3 PART I. DEFENSE, WAR, AND POLITICS I Ambivalent Duty: Soldiers, Indians, and Frontiersmen I 3 2 All Front, No Rear: Soldiers, Desert, and War 24 3 Chastise Them: Campaigns, Combat, and Killing 3 8 4 Internal Fissures: Soldiers, Politics, and Sectionalism 56 PART 11. -

English IV AP, DC, and HD 2021 Summer Reading

Northside ISD Curriculum & Instruction English IV AP, DC, & HD Summer Reading Welcome to Advance English IV Literature! Reading is one of the best things you can do to prepare yourself for the challenges of the upcoming school year and beyond. Now more than ever, it is important to sharpen your critical reading skills, expand your vocabulary and enhance your focus and imagination - all in the comfort of your own home. There’s no better way to accomplish this than by sitting down with a good book. We are asking that you, as an Advance Literature student, read at least one novel of your choice this summer. There is no other assignment than to read; however, be ready to complete a SUMMATIVE assignment on your summer reading book when school starts. Remember, you can choose any book you wish to read - it does not have to be on the list below. The following titles are included just to give you some ideas. The novels marked by an asterisk indicate those which are on the Northside approved book list. Other titles may contain adult themes and content, so we encourage you to do some research before selecting a title. You can check out digital books on Sora, Libby, and Overdrive through your school library. HAPPY READING! Romance 1. All the Ugly and Wonderful Things by Bryn Greenwood 2. Frankly In Love by David Yoon 3. The Importance of Being Earnest* by Oscar Wilde 4. Jane Eyre* by Charlotte Brontë 5. Just Listen by Sarah Dessen 6. Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel 7. -

2020 Book Discussion Groups

AFTERNOON BOOK DISCUSSION GROUP Afternoon Book Discussion Groups are held the third Wednesday of the Month at 1:30 p.m. in the Chester 2020 book County Library Burke Meeting Room. discussion EVENING BOOK DISCUSSION GROUP groups Evening Book Discussion Groups are held the first Monday of the Month at 7:30 p.m. in the Chester County Library Burke Meeting Room. If the book group meeting is cancelled due to inclement weather or due to an unexpected library closure, the scheduled book is pushed back to the next month and the other titles are moved according- ly. Please check the website for the most up-to-date list: bit.ly/chescolibs-bookgroups A Member of the Chester County Library System BOOK DISCUSSION GROUPS 450 Exton Square Parkway Exton, PA 19341 610-344-4210 [email protected] Monday - Thursday 9 a.m. - 9 p.m. Friday 9 a.m. - 6 p.m. Saturday 9:30 a.m. - 5 p.m. Sunday 1 p.m. - 5 p.m. www.chescolibraries.org join the conversation! 2020 Book Discussion groups Monday, September 28, 2020* Wednesday, August 19, 2020 (this is the October meeting) The Other Einstein by Marie Benedict The Triumph of Seeds by Thor Hanson EVENING BOOK Wednesday, September 16, 2020 DISCUSSION GROUP Monday, November 2, 2020 The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry First Monday of the Month Wednesday, October 21, 2020 (except where noted) Monday, December 7, 2020 Still Life by Louise Penny Burke Meeting Room ~ 7:30 p.m. The Thirteenth Tale by Diane Setterfield Wednesday, November 18, 2020 Monday, January 6, 2020 * Please note change in date from first Monday The Lost Girls of Paris by Pam Jenoff Magpie Murders by Anthony Horowitz AFTERNOON BOOK Wednesday, December 16, 2020 Monday, February 3, 2020 The Library Book by Susan Orlean My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite DISCUSSION GROUP Third Wednesday of the Month Monday, March 2, 2020 Burke Meeting Room ~ 1:30 p.m. -

Below Is the Full List of America's 100 Favorite Novels, in Alphabetical

Below is the full list of America’s 100 favorite novels, in alphabetical order by title: 1984 Gone with the Wind Swan Song A Confederacy of Dunces The Grapes of Wrath Tales of the City A Game of Thrones Great Expectations Their Eyes Were Watching A Prayer for Owen Meany The Great Gatsby God Things Fall Apart A Separate Peace Gulliver’s Travels This Present Darkness A Tree Grows in Brooklyn The Handmaid’s Tale To Kill a Mockingbird The Adventures of Tom Sawyer Harry Potter ** Twilight The Alchemist Hatchet War and Peace Alex Cross Mysteries** Heart of Darkness Watchers Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland The Help The Wheel of Time** Americanah The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Where the Red Fern Grows And Then There Were None The Hunger Games White Teeth Anne of Green Gables The Hunt for Red October Wuthering Heights Another Country* The Intuitionist Atlas Shrugged Invisible Man Beloved Jane Eyre Bless Me, Ultima* The Joy Luck Club The Book Thief Jurassic Park The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao Left Behind The Call of the Wild The Little Prince Catch-22 Little Women The Catcher in the Rye Lonesome Dove Charlotte’s Web Looking for Alaska The Chronicles of Narnia The Lord of the Rings** The Clan of the Cave Bear The Lovely Bones The Coldest Winter Ever The Martian The Color Purple Memoirs of a Geisha The Count of Monte Cristo Mind Invaders* Crime and Punishment Moby Dick The Curious Incident of the Dog in the The Notebook Night-Time One Hundred Years of Solitude The Da Vinci Code Outlander Don Quixote The Outsiders Doña Barbara* The Picture of Dorian Gray Dune The Pilgrim’s Progress Fifty Shades of Grey The Pillars of the Earth Flowers in the Attic Pride and Prejudice Foundation Ready Player One **Denotes a series title Frankenstein Rebecca *Not available through NLS Ghost The Shack Gilead Siddhartha The Giver The Sirens of Titan NLS availability vetted by The Godfather The Stand Gone Girl The Sun Also Rises 1 . -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

Building Order on Beacon Hill, 1790-1850

BUILDING ORDER ON BEACON HILL, 1790-1850 by Jeffrey Eugene Klee A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Spring 2016 © 2016 Jeffrey Eugene Klee All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number: 10157856 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10157856 Published by ProQuest LLC (2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 BUILDING ORDER ON BEACON HILL, 1790-1850 by Jeffrey Eugene Klee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Lawrence Nees, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Art History Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Bernard L. Herman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Post-Apocalyptic Naming in Cormac Mccarthy's the Road

“Maps of the World in Its Becoming”: Post-Apocalyptic Naming in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road Ashley Kunsa West Virginia University In The Road(2006), Cormac McCarthy’s approach to “naming differently” establishes the imaginative conditions for a New Earth, a New Eden. The novel diverges from the rest of McCarthy’s oeuvre, a change especially evident when the book is set against Blood Meridian because their styles and concomitant worldviews differ so strikingly. The style of The Road is pared down, elemental: it triumphs over the dead and ghostly echoes of the abyss and, alternately, over relentless ironic gesturing. And it is precisely in The Road’s language that we discover the seeds of the work’s unexpectedly optimistic worldview. The novel is best understood as a linguistic journey toward redemption, a search for meaning and pattern in a seemingly meaningless world — a search that, astonishingly, succeeds. Further, I posit The Road as an argument for a new kind of fiction, one that survives after the current paradigm of excess collapses, one that returns to the essential elements of narrative. Keywords: apocalypse / Cormac McCarthy / New Earth / The Road / style ormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize–winning tenth novel The Road (2006) gives us a vision of after: after the world has come to disaster, after any tan- Cgible social order has been destroyed by fire or hunger or despair. McCarthy here surrenders his mythologizing of the past, envisioning instead a post-apoca- lyptic future in which human existence has been reduced to the basics.1 Though the book remains silent on the exact nature of the disaster that befell the planet some ten years prior, the grim results are clear. -

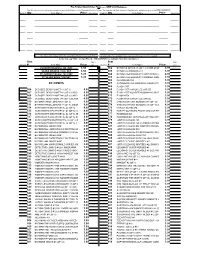

Price Qty X Price Item # Qty Item Name Price Qty X Price

Pre-Printed Short Order Form....…JUNE 2020 Releases Use this section to list any items wanted from any Order Booklet or the Pre-printed list that follows. You can also list Back Issues or Supplies here, and please give us the ITEM NUMBERS! Item # Qty Item Name Price Qty x Price Item # Qty Item Name Price Qty x Price _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ Use this section in place of the Previews Order Booklet if you wish. This is merely a list of the more popular items... you can order any item in the catalog! Items that say "NET" are Net Priced... NO DISCOUNT is available from the listed price! Item Qty x Item Qty x Quantity # Item Name Price Price Quantity # Item Name Price Price CURRENT BOARDS ( 100 ) NET 6.50 562 BATMANS GRAVE #8 (OF 12) CARD STOCK R GRAMPA4.99 VAR ED SILVER BOARDS ( 100 ) NET -

5^^Ife Porticoed and Clapboarded, the Benjamin Church House Observed the Rugged Life of Early Milwaukee from Its Fourth Street Site

VOLUME 38 NUMBER 2 PUBLISHED BY THE STAT WINTER, 1954-55 ;5^^ife Porticoed and clapboarded, the Benjamin Church house observed the rugged life of early Milwaukee from its Fourth Street site. Restored, and wearing the cloak of a little shrine, it began a new and a somewhat sheltered life in the city's pleasant Estabrook Park through the efforts of the Milwaukee County Historical Society. There., on Septem ber 14, 1939, it was named '^Kilhourntotvn House." ON THE COVER: Its fluted columns frosted with snow, its eaves fringed with glittering icicles, how proud it would he to hear the crunching footsteps of a winter wayfarer and the excla mation: ^'How lovely, how snug . how wise!'' This picture was taken by Don Mereen, Milwaukee; it was entered in the Historical Society's Photographic Competition, Autumn, 1954. The WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY is imhlislicfl by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 816 State Street, Madison 6, Wisconsin. Distrilmted to members as part of their dues (Annual Membership, $4.00; Contributinf;, SIO: Business and Professional, S25; Life, 1100; Sustaining, 5100 or more annually). ^ early subscription. 54.00; single numbers. 11.00. As of July 1, 1954, introductory offer for M;VV members only. Annual dues $1.00. Magazine subscription $3.00. Communications should be addressed lo the editor. The Society does not assume responsibility for statements made by contributors. Kntered as second-class matter at the post office at Madison, Wisconsin, under the act of August 24, 1912. ("opyright 1954 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Paid for in part by tlu- Alaria L. -

Winds of Change

Winds of Change the newsletter of the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition December 2009 E Huntington, WV www.ohvec.org Kicking the Coal Habit in WV - Solar Power Is A Reality by Mary Wildfire County neighborhood, so I volunteered, with the extra motive Solar power may sound like a great idea, but it isn’t of hoping to learn something that might prove useful to my practical unless you’re rich – or so many people think. But mate, who is now setting up our own system in Roane many ordinary West Virginians know otherwise. County. Thus I spent a long, sunny Saturday running around OVEC member with OVEC member Ron “RD” Dean sent Kate Lambdin, OVEC staffer Vivian looking at RD’s new Stockman an e-mail when on-grid system and his grid-tied solar electric the off-grid systems, system came on-line. “I’m all of which had first giddy with excitement!” he been installed in the said. “Just watching that 1980s, and then meter run backwards, upgraded over the having AEP owing us for years. electricity, was just too First, we funny. We produced more went to the ridgetop electricity today than we home of Dave would use in three days of Moore. His system is normal usage!” off-grid and he has Vivian didn’t have free gas, which time to check out his makes it easier to go system and those of some RD outside the Dean’s solar-powered Lincoln County home, solar – his heating, of the seven off-grid with a bumper sticker that says “I get my electricity from the cooking, water households in RD’s Lincoln SUN.” photo by Peggy Dean continued on p. -

“The Scalp Hunters”

“The Scalp Hunters” When I was at San Diego, a great many complaints were made by citizens there, and persons arriving from the Gila, of a gang of lawless men who had established a ferry over the Colorado, where not only they practised the greatest extortions, but committed murders and robberies . --Letter from General Persifer Smith to Capt. Irvin McDowell, May 25, 1850. The Yuma Crossing at the junction of the Colorado and Gila Rivers was once a key overland gateway to California. When the Gold Rush began in 1848, thousands of emigrants hurried across the hot Sonora Desert and forded the quarter-mile wide Colorado River at Yuma on San Diego County’s eastern border. One of the first ferry landings at Yuma was run by Dr. Able Lincoln, a physician from New York, who had recently fought in the U.S.-Mexico War. Mustered out at Mexico City in 1848, Lincoln had started for home but turned west when he heard word of the gold strikes in California. The difficult crossing of the Colorado River convinced Lincoln that a ferry business could be as valuable as gold. He built a boat and began carrying gold seekers across the river in January 1850. The ferry was lucrative success. Lincoln would write home to his parents in April, reporting he had ferried over 20,000 emigrants, all bound for the gold mines of California. “I have taken in over $60, 000,” he boasted. “My price, $1 per man, horse or mule $2, the pack $1, pack saddle 50 cents, saddle 25 cents.” Strangely, despite his profits, Lincoln did not expect to stay at the crossing longer than six months and “perhaps not more than a month.” “I shall sell at the first opportunity,” he wrote, adding ominously, “This is an unsafe place to live in.” Undisclosed in the letter to his family was the news that Lincoln had taken on an uninvited partner. -

Blood Meridian, Wise Blood, and Contemporary Political Discourse

Review of International American Studies FEATURES RIAS Vol. 13, Spring—Summer № 1 /2020 ISSN 1991—2773 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31261/rias.7623 A LITERARY HISTORY OF MENTAL CAPTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES Blood Meridian, Wise Blood, and Contemporary Political Discourse n July 15, 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump and Russia Manuel Broncano Rodríguez OPresident Vladimir Putin held a summit in Helsinki that Texas A&M immediately set off a chain reaction throughout the world.1 International University USA Even though the summit was all but forgotten for the most part in a matter of months, superseded by the frantic train https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0570-2680 of events and the subsequent bombardment from the media that have become the “new normal,” the episode remains as one of the most iconic moments of Donald Trump´s presidency. While the iron secrecy surrounding the conversation between the two dignitaries allowed for all kinds of speculation, the image of President Trump bowing to his Russian counterpart (indeed a treasure trove for semioticians), along with his declarations in the post-summit press conference, became, for many obser- vers in the U.S. and across the world, living proof of Mr. Trump´s subservient allegiance to Mr. Putin and his obscure designs. Even some of the most recalcitrant members of the GOP vented quite publicly their disgust at the sight of a president paying evident homage to the archenemy of the United States, as Vercingetorix kneeled down before Julius Cesar in recognition of the Gaul´s 1. The present article is partly based on a keynote lecture presented to the audiences of the “Captive Minds.