Palestinian Identity-Formation in Yarmouk: Constructing National Identity Through The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Report Enigma of 'Baqiya Wa Tatamadad'

Report Enigma of ‘Baqiya wa Tatamadad’: The Islamic State Organization’s Military Survival Dr. Omar Ashour* 19 April 2016 Al Jazeera Centre for Studies Tel: +974-40158384 [email protected] http://studies.aljazeera.n The Islamic State (IS) organization's military survival is an enigma that has yet to be fully explained, but even defeating it militarily will only address what is just one of the symptoms of a much larger regional political crisis [Associated Press] Abstract The Islamic State organization’s motto, ‘baqiya wa tatamadad’, literally translates to ‘remaining and expanding’. Along these lines, this report examines the reality of the Islamic State organization’s continued military survival despite being targeted by much larger domestic, regional and international forces. The report is divided into three sections: the first reviews security and military studies addressing theoretical reasons for the survival of militarily weaker players against stronger parties; the second focuses on the Islamic State (IS) organisation’s military capabilities and how it uses its power tactically and strategically; and the third discusses the Arab political environment’s crisis, contradictions in the coalition’s strategy to combat IS and the implications of this. The report argues that defeating the IS organization militarily may temporarily treat a symptom of the political crisis in the region, but the crisis will remain if its roots remain unaddressed. Background After more than seven months of the US-led air campaign on the Islamic State organization and following multiple ground attacks by various (albeit at times conflicting) parties, the organisation has managed not only to survive but also to expand. -

Status Report on Yarmouk Camp November 14, 2017

Status Report on Yarmouk Camp November 14, 2017 Executive Summary Following the capture of the Syria-Iraq border crossing near Abu Kamal, the Syrian government announced victory over ISIS in Syria. This announcement was made at a time when the Syrian government, supported by Hezbollah, Afghani Fatemiyoun, Iraqi Hezbollah al-Nujaba, and others, appeared poised to capture the border town of Abu Kamal – the last major population center held by ISIS in eastern Syria. However, the announcement ignored substantial ISIS strongholds elsewhere in Syria – including within the capital city of Damascus itself. ISIS entered Damascus city in April 2015, when it advanced against Free Syrian Army (FSA) aligned opposition groups and pro-government paramilitary groups in the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp on the southern edge of the city. Since then, Yarmouk Camp has been home to a ISIS, al-Qaeda aligned Jabhat al-Nusra (now known as Hai’yat Tahrir al-Sham), FSA factions, local Palestinian factions, pro-government paramilitary fighters, and government troops, making it a microcosm of the broader conflict. This report provides a brief overview of major events affecting Yarmouk Camp and profiles the major armed groups involved throughout. Brief History The Damascus neighborhood known as Yarmouk Camp hosted a thriving Palestinian community of approximately 160,000 Palestinian refugees until the FSA and Jabhat al-Nusra captured the area in December 2012. Since then, clashes between various groups, air campaigns, and sieges have decimated the Camp’s community and infrastructure. Less than 5% of the original population remains. Civilians suffer from severe food and water shortages even as they endure the constant threat of violence and displacement at the hands of the armed actors in the area. -

Syria Regional Crisis Emergency Appeal Progress Report

syria regional crisis emergency appeal progress report for the reporting period 01 January – 30 June 2020 syria regional crisis emergency appeal progress report for the reporting period 01 January – 30 June 2020 © UNRWA 2020 The development of the 2020 Syria emergency appeal progress report was facilitated by the Department of Planning, UNRWA. About UNRWA UNRWA is a United Nations agency established by the General Assembly in 1949 and is mandated to provide assistance and protection to a population of over 5.7 million registered Palestine refugees. Its mission is to help Palestine refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, West Bank and the Gaza Strip to achieve their full potential in human development, pending a just solution to their plight. UNRWA’s services encompass education, health care, relief and social services, camp infrastructure and improvement, microfinance and emergency assistance. UNRWA is funded almost entirely by voluntary contributions. UNRWA communications division P.O. Box 19149, 91191 East Jerusalem t: Jerusalem (+972 2) 589 0224 f: Jerusalem (+972 2) 589 0274 t: Gaza (+972 8) 677 7533/7527 f: Gaza (+972 8) 677 7697 [email protected] www.unrwa.org Cover photo: UNRWA is implementing COVID-19 preventative measures in its schools across Syria to keep students, teachers and their communities safe while providing quality education. ©2020 UNRWA photo by Taghrid Mohammad. table of contents Acronyms and abbreviations 7 Executive summary 8 Funding summary: 2020 Syria emergency appeal progress report 10 Syria 11 Political, -

UNRWA-Weekly-Syria-Crisis-Report

UNRWA Weekly Syria Crisis Report, 15 July 2013 REGIONAL OVERVIEW Conflict is increasingly encroaching on UNRWA camps with shelling and clashes continuing to take place near to and within a number of camps. A reported 8 Palestine Refugees (PR) were killed in Syria this week as a result including 1 UNRWA staff member, highlighting their unique vulnerability, with refugee camps often theatres of war. At least 44,000 PR homes have been damaged by conflict and over 50% of all registered PR are now displaced, either within Syria or to neighbouring countries. Approximately 235,000 refugees are displaced in Syria with over 200,000 in Damascus, around 6600 in Aleppo, 4500 in Latakia, 3050 in Hama, 6400 in Homs and 13,100 in Dera’a. 71,000 PR from Syria (PRS) have approached UNRWA for assistance in Lebanon and 8057 (+120 from last week) in Jordan. UNRWA tracks reports of PRS in Egypt, Turkey, Gaza and UNHCR reports up to 1000 fled to Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. 1. SYRIA Displacement UNRWA is sheltering over 8317 Syrians (+157 from last week) in 19 Agency facilities with a near identical increase with the previous week. Of this 6986 (84%, +132 from last week and nearly triple the increase of the previous week) are PR (see table 1). This follows a fairly constant trend since April ranging from 8005 to a high of 8400 in May. The number of IDPs in UNRWA facilities has not varied greatly since the beginning of the year with the lowest figure 7571 recorded in early January. A further 4294 PR (+75 from last week whereas the week before was ‐3) are being sheltered in 10 non‐ UNRWA facilities in Aleppo, Latakia and Damascus. -

REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA Received Little Or No Humanitarian Assistance in More Than 10 Months

currently estimated to be living in hard to reach or besieged areas, having REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA received little or no humanitarian assistance in more than 10 months. 07 February 2014 Humanitarian conditions in Yarmouk camp continued to worsen with 70 reported deaths in the last 4 months due to the shortage of food and medical supplies. Local negotiations succeeded in facilitating limited amounts of humanitarian Part I – Syria assistance to besieged areas, including Yarmouk, Modamiyet Elsham and Content Part I Barzeh neighbourhoods in Damascus although the aid provided was deeply This Regional Analysis of the Syria conflict (RAS) is an update of the December RAS and seeks to Overview inadequate. How to use the RAS? bring together information from all sources in the The spread of polio remains a major concern. Since first confirmed in October region and provide holistic analysis of the overall Possible developments Syria crisis. In addition, this report highlights the Map - Latest developments 2013, a total of 93 polio cases have been reported; the most recent case in Al key humanitarian developments in 2013. While Key events 2013 Hasakeh in January. In January 2014 1.2 million children across Aleppo, Al Part I focuses on the situation within Syria, Part II Information gaps and data limitations Hasakeh, Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, Hama, Idleb and Lattakia were vaccinated covers the impact of the crisis on neighbouring Operational constraints achieving an estimated 88% coverage. The overall health situation is one of the countries. More information on how to use this Humanitarian profile document can be found on page 2. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Humanitarian Bulletin Syrian Arab Republic Issue 43 | 13 – 26 February 2014 In this issue Truces enable delivery of some aid P.1 UNSC Resolution on humanitarian issues P.2 HIGHLIGHTS Escalation of fighting causes displacement P.2 Protection monitoring for Homs Old City evacuees P.2 Ceasefires enable delivery of Dar’a schools hit by explosions P.3 humanitarian assistance and New shelter guidelines address majority of IDPs P.3 return of civilians. SG report on children in armed conflict P.3 UN Security Council Overview of coordinated response resolution on humanitarian P.4 issues in Syria calls on UNICEF/ RRashidi Funding overview P.10 parties to the conflict to protect civilians and enable aid to reach all areas. Ceasefires enable some delivery of aid FIGURES Military truces and ceasefires have been implemented in some hard to access and Population 21.4 m besieged areas, with varying degrees of adherence, allowing partial and sporadic # of PIN 9.3 m humanitarian access. The ceasefire in Barzeh (Damascus) brokered earlier this month, has enabled the reported return of more than 1,000 people back to their homes. A UN # of IDPs 6.5 m inter-agency mission took place to the area on 25 February to conduct sectoral # of Syrian 2.5 m assessments and identify residual needs and gaps. While there the UN team met with a refugees in neighbouring representative from the countries and Governor’s office and North Africa community leaders and witnessed the mass FUNDING destruction of most parts of Barzeh, in particular the Old $ 2.3 billion City. -

The Plight of Palestinian Refugees in Syria in the Camps South of Damascus by Metwaly Abo Naser, with the Support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill

Expert Analysis January 2017 Syrian voices on the Syrian conflict: The plight of Palestinian refugees in Syria in the camps south of Damascus By Metwaly Abo Naser, with the support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill Introduction: the historical role of Palestinians the Oslo Accords in 1992 and the resulting loss by both the in Syria Palestinian diaspora in general and the inhabitants of the After they took refuge in Syria after the 1948 war, al-Yarmouk refugee camp in particular of their position as Palestinians refugees were treated in the same way as a key source of both material and ideological support for other Syrian citizens. Their numbers eventually reached the Palestinian armed revolution in the diaspora. This was 450,000, living mostly in 11 refugee camps throughout Syria due in part to the failure of the various Palestinian national (UNRWA, 2006). Permitted to fully participate in the liberation factions to identify new ways of engaging the economic and social life of Syrian society, they had the diaspora – including the half million Palestinians living in same civic and economic rights and duties as Syrians, Syria – in the Palestinian struggle for the liberation of the except that they could neither be nominated for political land occupied by Israel. office nor participate in elections. This helped them to feel that they were part of Syrian society, despite their refugee This process happened slowly. After the Israeli blockade of status and active role in the global Palestinian liberation Lebanon in 1982, the Palestinian militant struggle declined. struggle against the Israeli occupation of their homeland. -

Civilians Injured in Onslaught on Khan Al-Shih Camp in Damascus Outskirts"

"Civilians Injured in Onslaught on Khan Al-Shih Camp in Damascus Outskirts" Refugee sheltered in Khan Dannun Camp, in Damascus outskirts, announced dead Palestinian refugee families displaced from Qudsiya gain access to their homes Palestinian resident of Al-Aydeen Camp, in Homs, released from Syrian lock- ups after a one-year-internment 1,815 Palestinians died in refugee camps and communities in Syria until September 2016 Email:[email protected] - Tel:+442084530919 - Fax:+442084530994 - Mob:+447447423737 Victims Palestinian youth Suhail Moussa Ali, taking refuge in Khan Dannun Camp, was killed in bloody hostilities between the Syrian regime militias and opposition outfits in Dierkhabiya, in western Damascus Suburbs. The casualty is an officer at the 4th Armored Division, an elite mercenary of the Syrian Army whose primary purpose is to defend the Syrian government from internal and external threats. The division recruited hundreds of Palestinian refugees to stand in the forefronts of deadly hostilities with opposition squads. Latest Developments Reporting from Khan Al-Shih, an AGPS news correspondent said an offensive carried out by the regime Shilka self-propelled tanks left four refugees wounded. A shell was also slammed into Khan Al-Shih’s eastern neighborhood but caused no damage as it did not explode. At the same time, Syrian and Russian warplanes showered the nearby ranches and towns with Email:[email protected] - Tel:+442084530919 - Fax:+442084530994 - Mob:+447447423737 intensive air raids using the internationally-prohibited cluster bombs. Violent clashes burst out in the outer edges of the camp shortly afterwards. The onslaught comes at a time when Khan Al-Shih residents sounded distress signals over the tough siege slapped by the Syrian regime army on the camp for the 34th day running. -

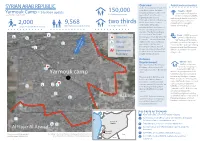

Yarmouk Map-Humanitarian Update

Overview: Assistance provided: SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC As the humanitarian situation in Syria deteriorates, Palestine Health: UNICEF d Situation update 150,000 refugees in Syria have become Yarmouk Camp - # of refugees pre crisis provided the Palestinian as of 20 December 2012 d Red Crescent and UNRWA Y Fighting in and around with enough health supplies for Yarmouk, a district of Damascus 10,000 people as well as 20 Y d that is home to the largest 2,000Y 9,568 two thirds midwifery kits, enough to ??????? internally displaced in shelters community of Palestine deliver 1,000 babies. Yapproximately left to Lebanon refugees in Syria, has been on Y the rise over the past several escalated on 16 December Food: UNICEF provided Attacked area following an attack by Syrian Air 2,000 food baskets for 1 Force jets , which left at least IDP families. WFP plans to Mosque eight people dead and many provide canned food enough for more injured. In the days 50,000 families and is prioritizing School following the attack, tens of Damascus and Rural Damascus Y city center with food distribution to meet 4km to Damascus Governorate to other areas of Syria and into rising needs. Boundary neighbouring Lebanon. Refugee Displacement: Shelter: New Over two thirds of the 150,000 shelters have been Palestine refugees have left opened, including one Yarmouk since the 16 December hosting 900 IDPs who attack2 . were in desperate need of aid. Yarmouk camp UNHCR and partners provided The Syrian Arab Red Crescent mattresses, blankets, hygiene has been helping refugees items and plastic sheeting and relocate to recently opened some 224 families have received shelters where 9,568 people are cash assistance. -

The Displaced People Outside Syria: 54 the Palestinian Refugees from Syria to Lebanon

1 Palestinians of Syria The Bleeding Wound 2 First Edition, February 2015 Action Group for Palestinians of Syria Palestinian Return Centre ISBN: 978-1-901924-21-3 3 4 Palestinians of Syria - The Bleeding Wound A Documentary Bi-Annual Field Report Monitors the Conditions of the Palestinians of Syria during the Second Half of 2014 Prepared by: Studies Department, Action Group for Palestinians of Syria (AGPS) Contributed to the preparation Ibrahim Al Ali Tarek Hammoud Ahmad Hosain Fayez Abu Eid Alaa Barghouth Nebras Ali Translated by Ibrahim Alejla Edited by Sophia Akram 5 6 INDEX - Introduction of the First Bi-Annual Report for 2014 9 - The General Situation and the Sequence of Events for the Conditions of the Palestinian Refugees in Syria During the Second Half of 2014: 11 - In the Palestinian Camps in Syria 12 1. Yarmouk Camp. 12 2. Khan Al Shieh Camp. 21 3. Dar’aa Camp. 28 4. Al Sayeda Zainab Camp. 29 5. Al Nairab Camp. 30 6. Al Aedein Camp-Homs. 34 7. Al Aedein Camp-Hama. 38 8. Khan Dannoun Camp. 38 9. Jaramana Camp. 40 10. Sbeina Camp. 40 11. Husseneia Camp. 41 12. Handarat Camp “Ain Al Tal Compound”. 42 - The Statistics During the Second Half of 2014: 44 Torture and Enforced Disappearance. 47 The Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Torture Victims. 48 Assassination and Kidnapping Victims. 50 Siege Victims. 50 Shelling Victims. 51 Explosions Victims. 52 Sniping and Clashes Victims. 53 - The Displaced People Outside Syria: 54 The Palestinian Refugees from Syria to Lebanon. 54 The Palestinian Refugees from Syria to Egypt. -

Regional Analysis Syria

Health: Reports of malnutrition have emerged from hospitals in Hama, Homs and REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA Idleb this month, as the lack of food and appropriate health care is for the first time leading to incidents of hospitalisation having been reported outside of besieged 30 October 2013 areas. This month has seen outbreaks of typhoid and polio, the upshot of which has been the launching of a mass immunisation campaign by the MoH and Part I – Syria UNICEF. WASH: Issues relating to water availability and sanitation facilities have been cited This Regional Analysis of the Syria conflict (RAS) is Content Part I an update of the September RAS and seeks to bring Overview as of the highest concern, as fighting has disrupted power supplies on several together information from all sources in the region How to use the RAS? occasions, leading to mass power outages and halting water pumping. The influx and provide holistic analysis of the overall Syria Possible developments of IDPs is further exerting pressure on water supply in relatively safe areas. crisis. While Part I focuses on the situation within Map - Latest developments Residents of IDP camps continue to live in conditions of dire sanitation, a problem Syria, Part II covers the impact of the crisis on the Information gaps and data limitations neighbouring countries. More information on how to compounded as the intense fighting has displaced thousands more and the Operational constraints use this document can be found on page 2. Please collective shelters become more crowded. note that place names which are underlined are Conflict developments October hyperlinked to their location on Google Maps.