Transcript (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Man Inside! and Other Stories Scott Am Tthew Beatty Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1994 Man Inside! and other stories Scott aM tthew Beatty Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Beatty, Scott aM tthew, "Man Inside! and other stories " (1994). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7089. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7089 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Man Inside!" and other stories by Scott Matthew Beatty A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Creative Writing) Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1994 Copyright © Scott Beatty, 1994. All rights reserved. 11 for Mom and Dad... and most of all, Jennifer, my Juicyfruit Editor Ill TABLE OF CONTENTS FRAGILE THINGS 1 WATCH CHILDREN 13 MAN INSIDE! 16 YOUR SEAT CUSHION ALSO FUNCTIONS AS A FLOTATION DEVICE 29 FAITH 45 THE PET HIERARCHY 54 DOODLES 67 SURVIVAL SKILLS 76 If— f i D^C 0 3 199^ ICWA STATE UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF GRADUATE ENGLISH The horror is this: In the end, it is simply a picture of empty meaningless blackness. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Big Hits Karaoke Song Book

Big Hits Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 3OH!3 Angus & Julia Stone You're Gonna Love This BHK034-11 And The Boys BHK004-03 3OH!3 & Katy Perry Big Jet Plane BHKSFE02-07 Starstruck BHK001-08 Ariana Grande 3OH!3 & Kesha One Last Time BHK062-10 My First Kiss BHK010-01 Ariana Grande & Iggy Azalea 5 Seconds Of Summer Problem BHK053-02 Amnesia BHK055-06 Ariana Grande & Weeknd She Looks So Perfect BHK051-02 Love Me Harder BHK060-10 ABBA Ariana Grande & Zedd Waterloo BHKP001-04 Break Free BHK055-02 Absent Friends Armin Van Buuren I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHK000-02 This Is What It Feels Like BHK042-06 I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHKSFE01-02 Augie March AC-DC One Crowded Hour BHKSFE02-06 Long Way To The Top BHKP001-05 Avalanche City You Shook Me All Night Long BHPRC001-05 Love, Love, Love BHK018-13 Adam Lambert Avener Ghost Town BHK064-06 Fade Out Lines BHK060-09 If I Had You BHK010-04 Averil Lavinge Whataya Want From Me BHK007-06 Smile BHK018-03 Adele Avicii Hello BHK068-09 Addicted To You BHK049-06 Rolling In The Deep BHK018-07 Days, The BHK058-01 Rumour Has It BHK026-05 Hey Brother BHK047-06 Set Fire To The Rain BHK021-03 Nights, The BHK061-10 Skyfall BHK036-07 Waiting For Love BHK065-06 Someone Like You BHK017-09 Wake Me Up BHK044-02 Turning Tables BHK030-01 Avicii & Nicky Romero Afrojack & Eva Simons I Could Be The One BHK040-10 Take Over Control BHK016-08 Avril Lavigne Afrojack & Spree Wilson Alice (Underground) BHK006-04 Spark, The BHK049-11 Here's To Never Growing Up BHK042-09 -

Seventy-First Congress

. ~ . ··-... I . •· - SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS ,-- . ' -- FIRST SESSION . LXXI-2 17 , ! • t ., ~: .. ~ ). atnngr tssinnal Jtcnrd. PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Couzens Harris Nor beck Steiwer SENATE Dale Hastings Norris Swanson Deneen Hatfield Nye Thomas, Idaho MoNDAY, April 15, 1929 Dill Hawes Oddie Thomas, Okla. Edge Hayden Overman Townsend The first session of the Seventy-first Congress comm:enced Fess Hebert Patterson Tydings this day at the Capitol, in the city of Washington, in pursu Fletcher Heflin Pine Tyson Frazier Howell Ransdell Vandenberg ance of the proclamation of the President of the United States George Johnson Robinson, Ark. Wagner of the 7th day of March, 1929. Gillett Jones Sackett Walsh, Mass. CHARLES CURTIS, of the State of Kansas, Vice President of Glass Kean Schall Walsh, Mont. Goff Keyes Sheppard Warren the United States, called the Senate to order at 12 o'clock Waterman meridian. ~~~borough ~lenar ~p~~~~;e 1 Watson Rev. Joseph It. Sizoo, D. D., minister of the New York Ave Greene McNary Smoot nue Presbyterian Church of the city of Washington, offered the Hale Moses Steck following prayer : Mr. SCHALL. I wish to announce that my colleag-ue the senior Senator from Minnesota [Mr. SHIPSTEAD] is serio~sly ill. God of our fathers, God of the nations, our God, we bless Thee that in times of difficulties and crises when the resources Mr. WATSON. I desire to announce that my colleague the of men shrivel the resources of God are unfolded. Grant junior Senator from Indiana [Mr. RoBINSON] is unav.oidably unto Thy servants, as they stand upon the threshold of new detained at home by reason of important business. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Table of Contents Item Transcript

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS ITEM TRANSCRIPT Mordko Brener. Full, unedited interview, 2009 ID UKR016.interview PERMALINK http://n2t.net/ark:/86084/b4r707 ITEM TYPE VIDEO ORIGINAL LANGUAGE RUSSIAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM TRANSCRIPT ENGLISH TRANSLATION 2 CITATION & RIGHTS 10 2021 © BLAVATNIK ARCHIVE FOUNDATION PG 1/10 BLAVATNIKARCHIVE.ORG DIGITAL COLLECTIONS ITEM TRANSCRIPT Mordko Brener. Full, unedited interview, 2009 ID UKR016.interview PERMALINK http://n2t.net/ark:/86084/b4r707 ITEM TYPE VIDEO ORIGINAL LANGUAGE RUSSIAN TRANSCRIPT ENGLISH TRANSLATION —Today is May 26, 2009. We are in the city of Vinnitsa [Vinnytsya]. Please, introduce yourself; tell us where and when you were born. I am Mordko Yudkovich Brener. I was born in the town Yanov, Kalininsky District. Now this town is called the village of Ivanovo. Before the war, people lived very happily, were friendly with the Ukrainian people, raised their children. Suddenly this happiness was cut short. The Great Patriotic War began. —Who were your parents? My parents also lived first in Yanov, but when I graduated from Jewish school in 1936, I went to Vinnitsa to study at a pedagogical technical school to be a teacher. I liked this profession and the school accepted me. My mother loved me very much and said that she would not live there without Mikhail—I was called Mikhail, but according to the documentation I was Mordko—and they left for Vinnitsa in ’36. Since ’36, I have always lived in Vinnitsa. I graduated from technical school in 1939 and when I turned eighteen, the army drafted me. The Second World War had already begun at this time. -

Officers, Officials, and Employees

CHAPTER 6 Officers, Officials, and Employees A. The Speaker § 1. Definition and Nature of Office § 2. Authority and Duties § 3. Power of Appointment § 4. Restrictions on the Speaker’s Authority § 5. The Speaker as a Member § 6. Preserving Order § 7. Ethics Investigations of the Speaker B. The Speaker Pro Tempore § 8. Definition and Nature of Office; Authorities § 9. Oath of Office §10. Term of Office §11. Designation of a Speaker Pro Tempore §12. Election of a Speaker Pro Tempore; Authorities C. Elected House Officers §13. In General §14. The Clerk §15. The Sergeant–at–Arms §16. The Chaplain §17. The Chief Administrative Officer D. Other House Officials and Capitol Employees Commentary and editing by Andrew S. Neal, J.D. and Max A. Spitzer, J.D., LL.M. 389 VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:53 Dec 04, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00389 Fmt 8875 Sfmt 8875 F:\PRECEDIT\WORKING\2019VOL02\2019VOL02.PAGETURN.V6.TXT 4473-B Ch. 6 PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE §18. The Parliamentarian §19. General Counsel; Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group §20. Inspector General §21. Legislative Counsel §22. Law Revision Counsel §23. House Historian §24. House Pages §25. Other Congressional Officials and Employees E. House Employees As Party Defendant or Witness §26. Current Procedures for Responding to Subpoenas §27. History of Former Procedures for Responding to Subpoenas F. House Employment and Administration §28. Employment Practices §29. Salaries and Benefits of House Officers, Officials, and Employees §30. Creating and Eliminating Offices; Reorganizations §31. Minority Party Employees 390 VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:53 Dec 04, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00390 Fmt 8875 Sfmt 8875 F:\PRECEDIT\WORKING\2019VOL02\2019VOL02.PAGETURN.V6.TXT 4473-B Officers, Officials, and Employees A. -

HOUSE. of REPRESENTATIVES-Tuesday, January 28, 1975

1610 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE January 28, 1975 would be informed by mall what benefits "Senior eitlzen.s a.re very proud;' ~~ ays. further morning business? If not~ morn would be coming. "They have worked or have been aupporte.d ing business is closed. In June. she received a letter saying that moat. of their l1vea by their working spou.s.e she was entitled to $173.40 a month. and do no~ 1in4 it. easy to a.ak for ilnanclal But the money did not come. Mrs. Menor asaist.ance. It. baa been our experience 'Ula~ 1:1 PROGRAM waited and waited, then she sent her social a prospective- appllea.nt has not received bla worker to apply !or her. check 1n due tim&. he or she Will no~ gn back Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, "And then the]' discovered. that they had down to 'the SSI omce to inquire about it." the Senate will convene tomorrew at 12 lost my whole rue and they had to start an o'clock noon. After the two leade.rs. or over again. So I"m supposed to be living on Now THE CoMPUTEa H&s CAoGHr 'UP $81.60. How do you get by on that? You ten their designees have been recogn)zed un The Social Beemity Administration. un der the standing order there will be a me. I pay $75 for my room and pay my own dertclok the Supplemental Security Income electricity. You ten me. How am I supposed period for the transaction of routine tSSif program on short notice and with in to eat?"' adequate staff last January, according to morning business of not to exceed 30 Mrs. -

Special Election Dates

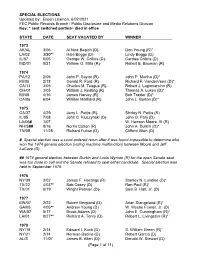

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

2015 Houston, TX Results

22001155 RReeggiioonnaall RReessuullttss Houston, TX February 5, 2015 – February 8, 2015 Petite Miss StarQuest Kamryn Landry - Home - Katy Kress Dance Revolution Junior Miss StarQuest Piper Click - How Will I Know - TopFlight Dance Company Teen Miss StarQuest Anna Perry - Found - Katy Kress Dance Revolution Miss StarQuest Cellise Brown - Fall Creek - Allegro West Academy of Dance Top Select Petite Solo 1 - Bella Hosemann - Fly - The Woodlands Dance Force 2 - Kamryn Landry - Home - Katy Kress Dance Revolution 3 - Claire Schunneman - Archangel Azrael - The Woodlands Dance Force 4 - Adissyn Williams - Stuff Like That There - Dance University 5 - Ally Woyt - Show Off - Staceys Dance Studio Top Select Junior Solo 1 - Oliva Steed - Paper Seas - Allegro West Academy of Dance 2 - Presley Gouge - Cavalier - TopFlight Dance Company 3 - Rosalyn Hutsell - Flatline - Allegro West Academy of Dance 4 - Emily Perry - I Cried - Dancin Bluebonnets 5 - Carson Conwell - Hero - Dancin Bluebonnets 6 - Aly Clapp - Glam - Staceys Dance Studio 7 - Sienna Johnson - My Immortal - TopFlight Dance Company 8 - Alyssa Hennessey - Sorry Seems To Be - Katy Kress Dance Revolution 9 - Kelsey Keiser - Habanera - Katy Kress Dance Revolution 10 - Darby Matte - Tears Of An Angel - Katy Kress Dance Revolution Top Select Teen Solo 1 - Anna Perry - Found - Katy Kress Dance Revolution 2 - Hollis Hernandez - Come On - Katy Kress Dance Revolution 3 - Brittney Myers - Light Of Gold - Allegro West Academy of Dance 4 - Macy Meinhadt - Locomotion - Staceys Dance Studio 5 - Hannah Coburn -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P.