CSEES MWSC 2014 Zhuk Pa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GREENGRASS, Paul 791 BOURN Gre ALFREDSON, Daniel 791 DJEVO

POINT Software Varaždin Str. 1 791 BOURN gre GREENGRASS, Paul (086.82)791 The Bourne ultimatum [Videosnimka] = [Bourneov ultimatum] / directed by Paul Greengrass ; screenplay by Tony Gilroy and Scott Z. Burns and George Nolfi ; based on the Novel by Robert Ludlum ; director of photography Oliver Wood ; music by J Zagreb : Continental Film, 2007. - 1 video DVD (110 min) : u bojama, sa zvukom (Dolby Digital) ; 12 cm Stv. nasl. i pod. o odg. sa špice. - Podnasl. na hrv. i drugim jez. ISBN 3856002123646 Svijet tajnih špijuna, vladinih tajnih programa i profi-ubojica, natjerivanje uzduž i poprijeko Globusa i jedan nepoznati identitet… Trči, Bourne, trči! Najtraženiji vladin super-špijun vraća se treći i posljednji put kako bi napokon odgovorio na pitanja o vlastitome identitetu te pronašao razloge koji su ga doveli u poziciju u kojoj je sad. A situacija u kojoj se našao Jason Bourne (Matt Damon) nije nimalo zavidna – CIA je upotrijebio svoje najsposobnije ekipe kako bi locirali njegov položaj, a na njega su nahuškali i najbolje profi-ubojice. Nakon što je ostao bez voljene Marie (Franka Potente), Bourne je još odlučniji u pronalaženju odgovora o vlastitoj prošlosti, ali i odlučan u namjeri da se osveti krivcima. Ishod njegova pothvata u mnogočemu ovisi o britanskome novinaru Simonu Rossu (Paddy Considine) koji od tajanstvenog izvora dobiva informacije o Vladinu tajnome programu 'Blackbriar' koji ima veze s Bourneovom prošlosti. Prvi Bourneov zadatak bit će doći do Rossa prije Vladinih operativaca, a ono što slijedi je još jedna potjera diljem zemaljskoga globusa – od Moskve, Londona i Pariza pa sve do tijesnih prolaza Tangiera i krovova New Yorka. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Guide to Wyoming and the West Collections

American Heritage Center University of Wyoming Guide to Wyoming and the West Collections Compiled By Rick Ewig, Lori Olson, Derick Hollingsworth, Renee LaFleur, Carol Bowers, and Vicki Schuster (2000) 2013 Version Edited By: Tyler Eastman, Andrew Worth, Audrey Wilcox, Vikki Doherty, and Will Chadwick (2012-2014) Introduction The American Heritage Center (AHC) is the University of Wyoming’s (UW) repository for historical manuscripts, rare books, and university archives. Internationally known for its historical collections, the AHC first and foremost serves the students and citizens of Wyoming. The AHC sponsors a wide range of scholarly and popular programs including lectures, symposia, and exhibits. A place where both experts and novices engage with the original sources of history, access to the AHC is free and open to all. Collections at the AHC go beyond both the borders of Wyoming and the region, and support a wide range of research and teachings activities in the humanities, sciences, arts, business, and education. Major areas of collecting include Wyoming and the American West, the mining and petroleum industries, environment and natural resources, journalism, military history, transportation, the history of books, and 20th century entertainment such as popular music, radio, television, and film. The total archival holdings of the AHC are roughly 75,000 cubic feet (the equivalent of 18 miles) of material. The Toppan Rare Books Library holds more than 60,000 items from medieval illuminated manuscripts to the 21st century. Subject strengths include the American West, British and American literature, early exploration of North America, religion, hunting and fishing, natural history, women authors, and the book arts. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

'Soviet Young Man:' the Personal Diaries and Paradoxical Identities

Copyright @2013 Australian and New Zealand Journal of European Studies http://www.eusanz.org/ANZJES/index.html Vol. 2013 5(2) ISSN 1837-2147 (Print) ISSN 1836-1803 (On-line) ‘Soviet Young Man:’ The Personal Diaries and Paradoxical Identities of ‘Youth’ in Provincial Soviet Ukraine during Late Socialism, 1970-1980s SERGEI I ZHUK Ball State University [email protected] Abstract: Using personal interviews and six diaries of contemporary male authors representing various social groups of urban residents in Soviet Ukraine (two from the cities, and four from towns), written in Russian and Ukrainian, from 1970 to the beginning of the 1980s, this article analyses archival documents and contemporary periodicals and explores the influences of the massive exposure to audio and visual cultural products from the “capitalist West” on the self-construction of identity of Soviet youth from provincial Ukrainian towns. This article seeks to study a concrete development of cultural détente from “the bottom up” perspective, avoiding the Moscow/Leningrad “elitist/conformist” emphasis of recent scholarship. Key words: détente, diary, identity, Soviet Ukraine, youth, Westernization During the period in the 1970s known as détente, when international tensions relaxed, the political and cultural centres of Soviet civilization such as Moscow and Leningrad opened to foreign guests from the “capitalist West,” and at the same time the provincial Soviet towns became exposed to large volumes of audio and visual information from capitalist countries on Soviet radio, television and movie screens. On March 4, 1972, a communist leader from one industrial region of Soviet Ukraine complained to local Komsomol ideologists, “There is too much capitalist West on our Soviet television screens today… Television shows (teleperedachi) about American music and films, about western fashions, prevail on our central channel from Moscow. -

Newsletter 01/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 01/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 198 - Januar 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 01/07 (Nr. 198) Januar 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, erotischer Natur, so floriert das Geschäft dem HD DVD Lager anzuschließen. So liebe Filmfreunde! dort mit harter Kost schon seit Jahren na- sollen in den kommenden Wochen bereits Auch die schönste Zeit geht einmal zu hezu ungebremst. Die Anzahl der in den die ersten freizügigen HD DVDs auf den Ende. Gemeint sind damit natürlich die USA auf DVD veröffentlichten Hardcore- Markt kommen, darunter der von Joone zwei Wochen Betriebsruhe ”zwischen den Filmen dürfte genauso groß sein wie die selbst inszenierte Hardcore-Blockbuster Jahren”, die wir uns traditionell selbst Veröffentlichungen in allen anderen Gen- PIRATES. Sonys Entscheidung zum Nein verschrieben haben. Pech also für uns, res. Wer also könnte noch ernsthaft an der für Hardcore-Produkte auf Blu-ray Disc dass wir jetzt schon wieder Mitte Januar wirtschaftlichen Wichtigkeit solcher Pro- könnte somit auf längere Sicht zum Aus haben, obgleich 2007 doch eigentlich gera- duktionen zweifeln? Egal welches Heim- für Blu-ray führen - vollkommen unabhän- de erst angefangen hat. Aber das liegt ver- kinomedium von der Industrie auf die gig davon, ob es vielleicht die bessere HD- mutlich an der etwas verzerrten Wahrneh- Konsumenten losgelassen wurde, die Technik ist oder nicht. Denn letztendlich mung der Zeit, die sich mit zunehmendem Pornoindustrie war stets eine der Ersten, zählen für die Konsumenten nur die ver- Alter einstellt. -

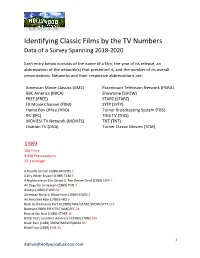

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020 Each entry below consists of the name of a film, the year of its release, an abbreviation of the network(s) that presented it, and the number of its overall presentations. Networks and their respective abbreviations are: American Movie Classics (AMC) Paramount Television Network (PARA) BBC America (BBCA) Showtime (SHOW) FREE (FREE) STARZ (STARZ) FX Movie Channel (FXM) SYFY (SYFY) Home Box Office (HBO) Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) IFC (IFC) THIS TV (THIS) MOVIES! TV Network (MOVIES) TNT (TNT) Ovation TV (OVA) Turner Classic Movies (TCM) 1989 150 Films 4,958 Presentations 33,1 Average A Deadly Silence (1989) MOVIES 1 A Dry White Season (1989) TCM 4 A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child (1989) SYFY 7 All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989) THIS 7 Always (1989) STARZ 69 American Ninja 3: Blood Hunt (1989) STARZ 2 An Innocent Man (1989) HBO 5 Back to the Future Part II (1989) MAX/STARZ/SHOW/SYFY 272 Batman (1989) SYFY/TNT/AMC/IFC 24 Best of the Best (1989) STARZ 16 Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) STARZ 140 Black Rain (1989) SHOW/MOVIES/MAX 85 Blind Fury (1989) THIS 15 1 [email protected] Born on the Fourth of July (1989) MAX/BBCA/OVA/STARZ/HBO 201 Breaking In (1989) THIS 5 Brewster’s Millions (1989) STARZ 2 Bridge to Silence (1989) THIS 9 Cabin Fever (1989) MAX 2 Casualties of War (1989) SHOW 3 Chances Are (1989) MOVIES 9 Chattahoochi (1989) THIS 9 Cheetah (1989) TCM 1 Cinema Paradise (1989) MAX 3 Coal Miner’s Daughter (1989) STARZ 1 Collision -

Stanley Kramer Papers LSC.0161

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft2x0nb09b No online items Finding Aid for the Stanley Kramer Papers LSC.0161 Processed by Charlotte Payne; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 4. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Stanley LSC.0161 1 Kramer Papers LSC.0161 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Stanley Kramer papers Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0161 Physical Description: 195 Linear Feet(316 boxes, 37 cartons, 2 oversize boxes.) Date (inclusive): 1945-1984 Abstract: Stanley Kramer (1913- ) was born in New York City. He began working in the film industry in the 1930s as a researcher, film editor, and writer, eventually working his way up to the position of associate producer by the early 1940s. Following World War II, he formed an independent motion picture company and produced modest-budget films. In 1951, he brought his company as an autonomous unit under the banner of Columbia Pictures. After 1955, Kramer directed and produced films receiving numerous awards and Academy Award nominations. The collection contains production files for Kramer's films, stills, scripts, audio tapes, ephemera, related correspondence, and memorabilia. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. -

Limits of Westernization During Cultural Détente in Provincial Society of Soviet Ukraine: a View from Below

Limits of Westernization during Cultural Détente in Provincial Society of Soviet Ukraine: A View from Below by Sergei I. Zhuk Abstract Using the personal diaries of young people from “provincial” towns and cities of Soviet Ukraine, this essay illustrates the obvious limits of Westernization during the cultural détente of the s in Soviet provincial society. The narratives of the personal diaries, writen during the 1970s and 80s, demonstrate that Soviet young people still shared the same communist ideological discourse, internalized it, imagined and perceived the outside world through the communist ideological “discursive lenses” and constructed their own identity, using the same communist ideological discursive elements. Keywords: Soviet identity, cultural détente, youth culture, personal diaries. ne Soviet high school student who Soviet towns became exposed to the massive Oreturned to the small Ukrainian town of audio and visual information from capitalist Novomoskovsk in , after ive years living countries on Soviet radio, television and movie in Poland with his parents, was shocked by screens. On March 4, 1972, a communist leader what he saw in Soviet Ukraine: from one industrial region of Soviet Ukraine complained to local Komsomol ideologists, I could not recognize my old neighborhood. It looked like the entire cultural landscape (peizazh) There is too much capitalist West on our Soviet of my native town has changed. Everybody was television screens today… Television shows dressed in Levi’s jeans; everybody listens here to (teleperedachi) about American music and the British bands Sweet, Slade, Geordie, Nazareth, iЧms, and western fashions prevaiЧ on our centraЧ UFO and T.Rex. In the movie theaters they show channeЧ from Moscow.