Three Hundred Years of Nephrology in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passages of Medical History. Edinburgh Medicine from 1860

PASSAGES OF MEDICAL HISTORY. Edinburgh Medicine from i860.* By JOHN D. COMRIE, M.D., F.R.C.P.Ed. When Syme resigned the chair of clinical surgery in 1869, Lister, who had begun the study of antiseptics in Glasgow, returned to Edinburgh as Syme's successor, and continued his work on antiseptic surgery here. His work was done in the old Royal Infirmary, for the present Infirmary had its foundation- stone laid only in 1870, and was not completed and open for patients until 29th October 1879. By this time Lister had gone to London, where he succeeded Sir William Fergusson as professor of clinical surgery in King's College in 1877. Another person who came to Edinburgh in 1869 was Sophia Jex Blake, one of the protagonists in the fight for the throwing open of the medical profession to women. Some of the professors were favourable, others were opposed. It is impossible to go into the details of the struggle now, but the dispute ended when the Universities (Scotland) Act 1889 placed women on the same footing as men with regard to graduation in medicine, and the University of Edinburgh resolved to admit women to medical graduation in October 1894. In the chair of systematic surgery Professor James Miller was succeeded (1864) by James Spence, who had been a demonstrator under Monro and who wrote a textbook, Lectures on Surgery, which formed one of the chief textbooks on this subject for many years. His mournful expression and attitude of mind gained for him among the students the name of " Dismal Jimmy." On Spence's death in 1882 he was succeeded by John Chiene as professor of surgery. -

Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell Now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society

Res Medica, Volume 268, Issue 2, 2005 Page 1 of 6 Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society Matthew H. Kaufman Professor of Anatomy, Honorary Librarian of the Royal Medical Society Abstract The two earliest diplomas in the possession of the Royal Medical Society were both awarded to George Joseph Bell, BA Oxford. One of these diplomas was his Extraordinary Membership Diploma that was awarded to him on 5 April 1839. Very few of these Diplomas appear to have survived, and the critical introductory part of his Diploma is inscribed as follows: Ingenuus ornatissimusque Vir Georgius Jos. Bell dum socius nobis per tres annos interfuit, plurima eademque pulcherrima, hand minus ingenii f elicis, quam diligentiae insignis, animique ad optimum quodque parati, exempla in medium protulit. In quorum fidem has literas, meritis tantum concessus, manibus nostris sigilloque munitas, discedenti lubentissime donatus.2 Edinburgi 5 Aprilis 1839.3 Copyright Royal Medical Society. All rights reserved. The copyright is retained by the author and the Royal Medical Society, except where explicitly otherwise stated. Scans have been produced by the Digital Imaging Unit at Edinburgh University Library. Res Medica is supported by the University of Edinburgh’s Journal Hosting Service url: http://journals.ed.ac.uk ISSN: 2051-7580 (Online) ISSN: ISSN 0482-3206 (Print) Res Medica is published by the Royal Medical Society, 5/5 Bristo Square, Edinburgh, EH8 9AL Res Medica, Volume 268, Issue 2, 2005: 39-43 doi:10.2218/resmedica.v268i2.1026 Kaufman, M. H, Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society, Res Medica, Volume 268, Issue 2 2005, pp.39-43 doi:10.2218/resmedica.v268i2.1026 Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society MATTHEW H. -

ROBERT BURNS and FRIENDS Essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows Presented to G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Kenneth Simpson See next page for additional authors Publication Info 2012, pages 1-192. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Book - Full Text is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author(s) Patrick G. Scott, Kenneth Simpson, Carol Mcguirk, Corey E. Andrews, R. D. S. Jack, Gerard Carruthers, Kirsteen McCue, Fred Freeman, Valentina Bold, David Robb, Douglas S. Mack, Edward J. Cowan, Marco Fazzini, Thomas Keith, and Justin Mellette This book - full text is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/burns_friends/1 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy G. Ross Roy as Doctor of Letters, honoris causa June 17, 2009 “The rank is but the guinea’s stamp, The Man’s the gowd for a’ that._” ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. -

Imperfect Notion at Present. the Faculty of Medical Professors Were

Letter I 15th July 1836 My dear Sharpey, The day before yesterday I got a summons from Carswell' to see him in some way or other as soon as possible and when I called on him I found you were the subject of conversation. From what he said I think there is every likelihood ofyour being chosen by the Council of the London University, but of course we can have but a very imperfect notion at present. The Faculty of Medical professors were to meet today to discuss the matter & Carswell says that their suggestion is very generally attended to by the Council. Mayo2 seemed to have an inclination to offer himself and Grainger3 is I suppose a candidate but Carswell seems to think that others as well as he is himselfwill be for having you. I need not say what tumult of feelings all this raised in my mind. The emoluments ofthe situation appear to be nearly £800 a year and you will deliver your lectures in much more advantageous circumstances there than you can do in Edinburgh. [I]t increases your chances of the Edinburgh chair4 and of preferment in every way and as far as I can see is most advantageous for you. I wrote you thus promptly in case it were possible for me to be of any use to you in this matter. Write me at all events and let me know what you are thinking ofthe matter. I weary to hear something ofSurgeons Square.5 Indeed I feel melancholy whenever I think of it. -

Of Science in the Mid-Nineteenth Century

Medical History, 1980, 24: 241-258. THERAPEUTIC EXPLANATION AND THE EDINBURGH BLOODLETTING CONTROVERSY: TWO PERSPECTIVES ON THE MEDICAL MEANING OF SCIENCE IN THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY by JOHN HARLEY WARNER* JOHN HUGHES BENNErT (1812-1875), the Edinburgh pathologist, microscopist, and professor ofthe institutes ofmedicine, remarked in a lecture delivered before a class of medical students in 1849: Whilst pathology has marched forward with great swiftness, therapeutics has followed at a slower pace. What we have gained by our rapid progress in the science of disease has not been followed up with an equally flattering success in an improved method of treatment. The science and art ofmedicine have not progressed hand in hand.1 Bennett's comment reflects the striking paradox of medicine in the first half of the nineteenth century: medical science was progressing at an unprecedentedly rapid rate, yet therapeutics - what the physician actually did to the patient - was in a troubling state of confusion. Moreover, the meaning of physiology and pathology for the treatment ofdisease was not at all obvious. Medical men disagreed widely on whether the application of the products of laboratory science, or of empirical observation, represented the best approach to advancing medical practice. The disparity ofphysicians' perceptions ofthe proper relationships among scientific knowledge, medical theory, and therapeutic practice in the mid-nineteenth century emerged with striking clarity from the debate on bloodletting in Edinburgh.2 The principal foci of the discourse on bloodletting that flourished in the mid-1850s were two species oftherapeutic theory. One type oftheory was designed to explain, justify, or guide therapeutic management; the second type of theory sought to explain why therapeutic practice had changed. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part One ISBN 0 902 198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART I A-J C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Innes Smith Collection

Innes Smith Collection University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: Special Collection Title: Innes Smith Collection Scope: Books on the history of medicine, many of medical biography, dating from the 16th to the early 20th centuries Dates: 1548-1932 Extent: 330 vols. Name of creator: Robert William Innes Smith Administrative / biographical history: Robert William Innes Smith (1872-1933) was a graduate in medicine of Edinburgh University and a general practitioner for thirty three years in the Brightside district of Sheffield. His strong interest in medical history and art brought him some acclaim, and his study of English-speaking students of medicine at the University of Leyden, published in 1932, is regarded as a model of its kind. Locally in Sheffield Innes Smith was highly respected as both medical man and scholar: his pioneer work in the organisation of ambulance services and first-aid stations in the larger steel works made him many friends. On Innes Smith’s death part of his large collection of books and portraits was acquired for the University. The original library is listed in a family inventory: Catalogue of the library of R.W. Innes-Smith. There were at that time some 600 volumes, but some items were sold at auction or to booksellers. The residue of the book collection in this University Library numbers 305, ranging in date from the early 16th century to the early 20th, all bearing the somewhat macabre Innes Smith bookplate. There is a strong bias towards medical biography. For details of the Portraits see under Innes Smith Medical Portrait Collection. -

Colour and Sound to Medical Studies, and Graduated As Doctor of Medicine in 1819

Feb 9, r882 J NATURE 339 de Alwis, who "as merely employed to make accurate copies of Farhelia in the Mediterranean his brother's drawing,, need not be brouglit forward; Mr. Moore was perfectly aware who made the original drawings from nature. ON the morning of the 27th inst. a curious sight was wit· It is sati:;factory to know that the preface "ill contain an ac nessed at this place. I was miling on the Mediterranean, and knowledgment of the real artist, but common honesty requires the day was hot and sunny. A slight haze came on, and about his name to be printed on every plate that he drew instead of noon a large halo with an orange tint surrounded the sun. "C. F. Moore." HENRY TRIM EN Shortly afterwards two mock suns appeared, one on each side }{, Bot. Gardens, Peradeniya, Ceylon, January 9 of the ring round the central sun. They were also tinged with an orange colour, and appeared to have comet-like tails. Re flected in the still blue water thev were even more distinct than The Collection of Meteoric Dust-A Suggestion when looked at direct, as the wa'ter cut off the 'un's rays. This IN the Report of the Committee on Meteoric Dust, given in >ingular spectacle lasted more than an hour, and was seen by your report of the last meeting of the British Association many. The boatmen predicted bad weather, but it has not yet (NATURE, val. xxiv. p. 462), Prot. Schuster refers to the diffi. come. All through Tanuary we have had brilliant summer days, culty "found in the determination of the locality in "hich the with cold starlight nights-the minimum thermometer descend observations should be conducted," as there are but few acces ing to 38• and 36• almost every night. -

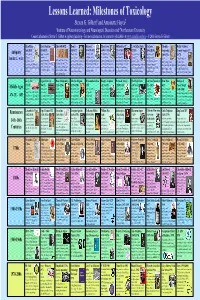

Lessons Learned: Milestones of Toxicology Steven G

Lessons Learned: Milestones of Toxicology Steven G. Gilbert1 and Antoinette Hayes2 1Institute of Neurotoxicology and Neurological Disorders and 2Northeastern University Contact information: Steven G. Gilbert at [email protected] – For more information, its interactive (clickable) at www.asmalldoseof.org – © 2006 Steven G. Gilbert Shen Nung Ebers Papyrus Gula 1400 BCE Homer Socrates Hippocrates Mithridates VI L. Cornelius Sulla Cleopatra Pedanius Mount Vesuvius 2696 BCE 1500 BCE 850 BCE (470-399 BCE) (460-377 BCE) (131-63 BCE) 82 BCE (69-30 BCE) Dioscorides Erupted August 24th Antiquity The Father of Egyptian records Wrote of the Charged with Greek physician, Tested antidotes Lex Cornelia de Experimented (40-90 CE) 79 CE Chinese contains 110 use of arrows religious heresy observational to poisons on sicariis et with strychnine Greek City of Pompeii & 3000 BCE – 90 CE pages on anatomy Sumerian texts refer to a medicine, noted poisoned with venom in the and corrupting the morals approach to human disease himself and used prisoners veneficis –law and other poisons on pharmacologist and Herculaneum and physiology, toxicology, female deity, Gula. This for tasting 365 herbs and epic tale of The Odyssey of local youth. Death by and treatment, founder of as guinea pigs. Created against poisoning people or prisoners and poor. Physician,wrote De Materia destroyed and buried spells, and treatment, mythological figure was said to have died of a toxic and The Iliad. From Greek Hemlock - active chemical modern medicine, named mixtures of substances prisoners; could not buy, Committed suicide with Medica basis for the by ash. Pliny the Elder recorded on papyrus. -

PATRICK HERON WATSON (1832-1907)* by WILLIAM N

AN EDINBURGH SURGEON OF THE CRIMEAN WAR- PATRICK HERON WATSON (1832-1907)* by WILLIAM N. BOOG WATSON IN March 1854 Britain and France declared war on Imperial Russia which was already at war with Turkey, and in September of that year, after an abortive campaign in Bulgaria, an expeditionary force proceeded to the Black Sea, having the Crimea as its field of operations and Constantinople as its base. In order to satisfy the need for medical officers in the campaign a large number of young doctors came forward for enrolment as assistant surgeons in the army and others volunteered to serve in civilian hospitals sent out to the eastern Mediterranean. Government reports, medical historians and writers of biography have fully detailed the failures and errors of medical administration in the Crimean war; the consequent tragedies and catastrophes; and the part played by Miss Nightingale and her ladies in nursing the sick and the wounded. A small number of regimental surgeons have chronicled their experiences with fighting units in the field, but very little has been recorded of the life and work of surgeons in the hospital service and something of interest can, therefore, be gleaned from the letters written by Patrick Heron Watson, a young Edinburgh doctor, during his army service in the years 1854 and 1855. The first part ofthis paper is based largely on those letters, which have been made available through the kindness of his grandson, Commander Patrick Haig Ferguson. The latter part of the paper is concerned with his career as a surgeon of high repute in Scotland. -

Sheonagh M. K. Martin Phd Thesis

WILLIAM PULTENEY ALISON: ACTIVIST, PHILANTHROPIST AND PIONEER OF SOCIAL MEDICINE Sheonagh M. K. Martin A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1997 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2815 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons License William Pulteney Alison: Activist Philanthropist and Pioneer of Social Medicine. Sheonagh M. K. Martin Ph.D 31st March 1997 Abstract The thesis looks in detail at three inter-related aspects of Alison's life. It examines, firstly, his role in the development of Edinburgh's rudimentary 'health' network, achieved through the expansion of the existing medical charity structure and the introduction of a more interventionist and coordinated approach to the city's health problems. It traces, secondly, the development of Alison's social thought - in 1820 he believed that medical and practical relief for the poor could and should be supplied through the voluntary charities and only when that proved unsatisfactory through the poor law, whereas by 1840 he argued that public health should be the responsibility of government and that the excessive increase in poverty and disease in Scotland, which he believed had occurred, was proof that the charitable and legal relief provided was inadequate. Finally, Alison's influence on the passage of Scottish poor law and public health legislation in the 1840s and 1850s is examined - the latter involving an assessment of how far he was responsible for the legislative delay. -

Communities and Interactions in Nineteenth-Century Scottish And

Communities and Interactions in Nineteenth-Century Scottish and English Toxicology Holly Easton In fulfilment of the degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History, University of Canterbury Supervisors: Heather Wolffram and David Monger 2017 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 1 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: Toxicology and Tertiary Education ............................................................................... 12 Scotland, 1800-49 .................................................................................................................... 13 England, 1800-49 .................................................................................................................... 16 The Second Half of the Century ............................................................................................... 20 Chapter Two: Toxicology and Legal Systems ....................................................................................... 29 Scotland, 1800-49 .................................................................................................................... 30 England, 1800-49 ...................................................................................................................