ONLY CONNECT: a MEMOIR by Beert Verstraete

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CV SN-Deleeuw

The University of Northern British Columbia Northern Medical Program 3333 University Way, Prince George, BC, V2N 4Z9 [email protected] S ARAH N. DE L EEUW 1-250-960-5993 POSITIONS (April 2016 - 2021). Appointed Adjunct Research Professor, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies. Carleton University. (May 2013). Promoted and Tenured to Associate Professor, Northern Medical Program, The University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC), Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia (UBC). Affiliate status, Departments of Geography and Community Health Science, UNBC. (May 2013). Affiliate Associate Professor, School of Population and Public Health, The University of British Columbia (UBC). (July 2008 – May 2013). Assistant Professor, Northern Medical Program, The University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC), Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia (UBC). Affiliate status, Departments of Geography and Community Health Science, UNBC. (July 2008 – May 2013). Affiliate Assistant Professor, School of Population and Public Health, The University of British Columbia (UBC). EDUCATION 2007-2008. Post-Doctoral Fellowship. Department of Geography and Regional Planning. University of Arizona. Tucson Arizona. Supervisor: Dr. John Paul Jones 2003-2007. Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD). Department of Geography, Queen’s University. Thesis title: Artful Places: Creativity and Colonialism in British Columbia’s “Indian” Residential Schools. Supervisors: Dr. Audrey Kobayashi and Dr. Anne Godlewska Examiner: Dr. Cole Harris 2000-2002. Master of Arts (MA). Interdisciplinary Studies, English and Geography, University of Northern British Columbia. Thesis title: Along Highway 16: A Creative Meditation on the Geography of Northern British Columbia. Supervisor: Dr. Julia Emberley Examiner: Dr. Kevin Hutchins 1991-1996. Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA). -

New KPU Regalia Reflects New Chancellor's Indigenous Roots

New KPU regalia reflects new chancellor’s Indigenous roots Sam Stringer is a graduate of the Wilson School of Design at Kwantlen Polytechnic University. She was also a staff member at the school. But her longstanding relationship with KPU doesn’t end there. Stringer is now the designer of the new regalia for KPU’s president and incoming chancellor. “I feel so honoured that they thought of me for this project. I get to do something for my family and I love getting to work with Kwantlen again.” Stringer quickly embraced the opportunity to create new regalia for Chancellor Kim Baird, who will be installed as KPU’s third chancellor on Oct. 19. The president’s regalia was also re-designed and complements that of the chancellor. “We wanted to make the regalia look a bit more modern. We have a new chancellor so the new regalia has a bit of Kim’s heritage, a little bit of the Tsawwassen First Nation, Coast Salish design aspect. That was the inspiration behind everything,” says Stringer. She did a lot of research into the design elements. She was also introduced to a cedar weaver at the Tsawwassen First Nation who added traditional cedar weaving to the sleeves of the new robes. “The creation of this regalia is an important recognition of the traditional territory KPU campuses rest on. Sam Stringer has been very thoughtful in ensuring her design upholds important values to KPU but also respects my heritage as a Tsawwassen and Coast Salish woman,” says Baird. “I couldn't be more thrilled about how she has integrated these values and worked with Tsawwassen artists and incorporated these important details into the design of the robes. -

Jay Ruzesky Ing to Get Clean in Vancouver’S Thunder River by Tony Cosier (Thistledown $18.95) Downtown Eastside

PHOTO ROBSON PETER Reprinted thirteen times, Anne Cameron’s Daughters of Copper Woman is one of the bestselling books of fiction published from and about British Columbia. WINNER ANNEANNE CAMERONCAMERON Since 1995, BC BookWorld and the Vancouver Public Library have proudly sponsored the Woodcock Award and the Writers Walk at 350 West Georgia Street in Vancouver. 16TH ANNUAL GEORGE WOODCOCK LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD FOR AN OUTSTANDING LITERARY CAREER IN BRITISH COLUMBIA ANNE CAMERON BIBLIOGRAPHY: Novels & Short Stories: Dahlia Cassidy (2004) • Family Resemblances (2003) • Hardscratch Row (2002) • Sarah's Children (2001) • Those Lancasters (2000) • Aftermath (1999) • Selkie (1996) • The Whole Dam Family (1995) • Deeyay and Betty (1994) • Wedding Cakes, Rats and Rodeo Queens (1994) • A Whole Brass Band (1992) • Kick the Can (1991) • Escape to Beulah (1990) • Bright's Crossing (1990) • South of an Unnamed Creek (1989) • Women, Kids & Huckleberry Wine (1989) • Tales of the Cairds (1989) • Stubby Amberchuk & The Holy Grail (1987) • Child of Her People (1987) • Dzelarhons: Mythology of the Northwest Coast (1986) • The Journey (1982) • Daughters of Copper Woman (1981) • Dreamspeaker (1979). Poetry: • The Annie Poems (1987) • Earth Witch (1983) Children's Books: T'aal: The One Who Takes Bad Children (1998) • The Gumboot Geese (1992) • Raven Goes Berrypicking (1991) • Raven & Snipe (1991) • Spider Woman (1988) • Lazy Boy (1988) • Orca's Song (1987) • Raven Returns the Water (1987) • How the Loon Lost her Voice (1985) • How Raven Freed the Moon -

Literary Review of Canada – June 2021

$7.95 1 2 STEPHEN MARCHE Our Cult of Work J. R. MCCONVEY The Smart Set 0 2 E ANNA PORTER An Artistic Battle DAVID MACFARLANE Taxi! N U J Literary Review of Canada A JOURNAL OF IDEAS BOLD FICTION NEW CALLS TO ACTION UNTOLD HISTORIES “Foregone is a subtle meditation on a life “Slender, thoughtful ... it grants new composed of half-forgotten impulses urgency to old questions of risk and and their endless consequences.” politics … An entertaining gloss on an —Marilyn Robinson, enduring conundrum.” author of Housekeeping and Gilead —Kirkus RECLAIMED VOICES "An astonishing book about folks from all over, many of whom have been through total hell but have somehow made their way out... You never know who's driving you. " — Margaret Atwood, on Twitter “Urgent, far-reaching and with a profound generosity of care, the wisdom in On Property is absolute. We cannot afford to ignore or defer its teachings.” —Canisia Lubrin, author of The Dyzgraphxst 2020 FOYLES BOOK OF THE YEAR “One of the best books of this dreadful year ... an extraordinary feat of ventriloquism delivered in a lush, lyrical prose that dazzles readers from the get-go. ” —Sunday Times “Well-researched and moving ... For readers who have ever wondered about life behind bars, this is a must-read.” — Publishers Weekly AVAILABLE IN BOOKSTORES AND ONLINE NOW. “[Magnason] tries to make the reader under- stand why the climate crisis is not widely per- ceived as a distinct, transformstive event ... The fundamental problem ... is time. Climate change is a disaster in slow motion.” —The Economist “[Pheby’s] compassion for Lucia Joyce has an extraordinary effect: it speaks up www.biblioasis.com for girls and women everywhere.” —Lucy Ellmann, /biblioasis @biblioasis @biblioasis_books author of Ducks, Newburyport JUNE 2021 ◆ VOLUME 29 ◆ NUMBER 5 A JOURNAL OF IDEAS FIRST WORD COMPELLING PEOPLE PEDAGOGY Clippings Copy Cats Queen of Queen’s Kyle Wyatt A little from column A, The woman behind the writers 3 a little from column B J. -

Queer Canlit: CANADIAN LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, and TRANSGENDER ( LGBT ) LITERATURE in ENGLISH

Photo: Robert Giard, 1994. Copyright: Estate of Robert Giard This exhibition is dedicated to Jane Rule (1931 –2007). Queer CanLit: CANADIAN LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER ( LGBT ) LITERATURE IN ENGLISH An Exhibition Curated by Scott Rayter, Donald W. McLeod, and Maureen FitzGerald Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies University of Toronto 9 June – 29 August 2008 isbn 978-0-7727-6065-4 Catalogue and exhibition by Scott Rayter, Donald W. McLeod, and Maureen FitzGerald General editor P.J. Carefoote Exhibition installed by Linda Joy Digital photography by Bogda Mickiewicz and Paul Armstrong Catalogue designed by Stan Bevington Catalogue printed by Coach House Press, Toronto library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Rayter, Scott, 1970 –* Queer CanLit : Canadian lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) literature in English : an exhibition / by Scott Rayter, Donald W. McLeod, and Maureen FitzGerald. “Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, 9 June –29 August 2008.” Includes bibliographical references. isbn 978-0-7727-6065-4 1. Gays’ writings, Canadian (English) –Exhibitions. 2. Bisexuals’ writings, Canadian (English) –Exhibitions. 3. Transgender people’s writings, Canadian (English) –Exhibitions. 4. Canadian literature (English) –20th century –Bibliography –Exhibitions. I. McLeod, Donald W. (Donald Wilfred), 1957 – II. FitzGerald, Maureen, 1942 – III. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library IV. Title. PS8089.5.G38R39 2008 016.8108'092066 C2008-901963-6 Contents -

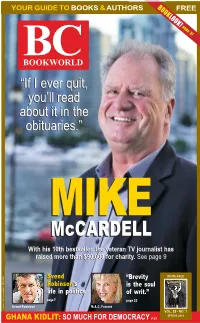

If I Ever Quit, You'll Read About It in the Obituaries

YOUR GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS BOOK FREE LOOK! BC page 37 BOOKWORLD “If“If II everever quit,quit, you’llyou’ll readread aboutabout itit inin thethe obituaries.”obituaries.” MIKEMIKE McCARDELLMcCARDELL WithWith hishis 10th10th bestseller,bestseller, thethe veteranveteran TVTV journalistjournalist hashas raisedraised moremore thanthan $90,000$90,000 forfor charity.charity. SeeSee pagepage 99 SvendSvend “Brevity INVIOLABLE #40010086 Robinson’sRobinson’s is the soul AGREEMENT lifelife inin politicspolitics of writ.” MAIL pagepage 77 page 25 PUBLICATION Svend Robinson M.A.C. Farrant VOL. 28 • NO. 1 SPRING 2014 GHANA KIDLIT: SO MUCH FOR DEMOCRACY P.20 Mark Your Calendar May 16th - 18th, 2014 at Prestige Harbourfront Resort & Convention Centre Salmon Arm, BC Presenters for 2014: Diana Gabaldon Howard White Treat yourself C.C. Humphreys to an inspiring Gail Anderson-Dargatz Victoria Day Gary Geddes David Essig weekend on the Ursula Maxwell-Lewis shores of Ann Eriksson beautiful Carmen Aguirre Shelagh Jamieson Shuswap Lake Carolyn Swayze Up-comingUp-coming Events: Events: April 26-28, 2014 AGM Weekend Conference – Victoria, BC on the May 3, 2014 Poetic Imaginations: A One-day Poetry Conference – New Westminster, BC Lake A Festival for Writers June 8, 2014 Write on the Beach: Information on workshops, Saturday night entertainment, banquet, coffee The Business of Writing – Crescent Beach, BC house and more at: www.saow.ca For more info about FBCW and these great events visit bcwriters.ca “Such an amazing experience— I need to come back to -

Report to the Board: October 2019

KPU offers the first design program in Canada with zero textbook cost This fall, Kwantlen Polytechnic University’s Wilson School understanding of design as a career. Skills developed include of Design will launch the Foundations in Design program drawing, 2D and 3D design as well as developing a creative with zero textbook cost (ZTC)– the first design program in process. Canada to be fully ZTC. “Now a ZTC program, students in Foundations in Design will “The Foundations in Design program provides exceptional leave with a tool kit of knowledge necessary to enter the training for students who wish to embark on a career in creative field. The essential skills needed for any career within design. By removing all textbook costs, our faculty have the design industry,” says Natasha Campbell, Foundations in made training in design innovation even more affordable,” Design program coordinator and instructor. says Rajiv Jhangiani, associate vice provost, open education at KPU. With the new Foundations in Design ZTC program and the addition of two ZTC programs in the Faculty of Arts this “We would like to continue to support our students with summer, KPU has doubled the number of credentials that can the ability to save on costs for their education and this has be obtained without textbook costs for the 2019-20 academic been further enhanced by expanding access to other digital year. The other ZTC programs – formerly called Zed Creds – resources and online subscriptions,” says Andhra available at KPU are Associate of Arts in General Studies, Goundrey, interim dean of the Wilson School of Design at Associate of Arts in Sociology, Diploma in General Studies, KPU. -

Book*Hug Spring 2021 Catalogue (PDF)

Radically optimistic.* * 2021 Spring/Summer Catalogue bookhugpress.ca Bookhug_Cat_Cover_Spring_21.indd All Pages 2020-09-18 8:32 AM BOOK*HUG PRESS Co-Publishers: Jay Millar and Hazel Millar We’ve Moved 401 Richmond Street West, Suite 350, Toronto, Ontario, M5v 3A8, Canada www.bookhugpress.ca 416-994-5804 [email protected] @bookhugpress bookhug @bookhug_press Catalogue cover by Gareth Lind / Lind Design Book*hug Press acknowledges that the land on which we operate is the traditional territory of many nations, including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples. We recognize the enduring presence of many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples and are grateful for the opportunity to meet and work on this territory. Spring & Summer 2021 FRONTLIST FICTION WE, Jane Aimee Wall A remarkable debut about intergenerational female relationships and resistance found in the unlikeliest of places, We, Jane explores the precarity of rural existence and the essential nature of abortion. Searching for meaning in her Montreal life, Marthe begins an intense friendship with an older woman, also from Newfoundland, who tells her a story about purpose, about a duty to fulfill. It’s back home, and it goes by the name of Jane. Marthe travels back to a small town on the island with the older woman to continue the work of an underground movement in 60s Chicago: abortion services performed by women, always referred to as Jane. She commits to learning how to continue this legacy and protect such essential knowledge. But the nobility of her task and the reality of small- town, rural life compete, and personal fractures in the small movement become clear. -

Download Full Issue

89646_TXT 2/17/05 9:42 AM Page 1 Canadian Literature/ Littératurecanadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number , Winter Published by The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Laurie Ricou Associate Editors: Laura Moss (Reviews), Glenn Deer (Reviews), Kevin McNeilly (Poetry), Réjean Beaudoin (Francophone Writing) Past Editors: George Woodcock (–), W.H. New, Editor emeritus (–), Eva-Marie Kröller (–) Editorial Board Heinz Antor University of Cologne, Germany Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Irene Gammel RyersonUniversity Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Ursula Mathis-Moser University of Innsbruck, Austria Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Leslie Monkman Queen’s University Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Élisabeth Nardout-Lafarge Université de Montréal Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke David Staines University of Ottawa Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Penny van Toorn University of Sydney, Australia Mark Williams University of Canterbury, New Zealand Editorial Réjean Beaudoin and Laurie Ricou De quoi l’on cause / Talking Point Articles Anne Compton The Theatre of the Body: Extreme States in Elisabeth Harvor’s Poetry Réjean Beaudoin La Pensée de la langue : entretien avec Lise Gauvin Susan Fisher Hear, Overhear, Observe, Remember: A Dialogue with Frances Itani Valerie Raoul You May Think This, But: An Interview with Maggie de Vries John Moffatt and Sandy Tait I Just See Myself as an Old-Fashioned Storyteller: A Conversation with Drew Hayden Taylor 89646_TXT 2/17/05 9:42 AM Page 2 Poems Shane Rhodes Michael deBeyer , John Donlan Hendrik Slegtenhorst Jane Munro Books in Review Forthcoming book reviews are available at the Canadian Literature web site: http://www.cdn-lit.ubc.cahttp://www.canlit.ca Authors Reviewed Steven Galloway Jennifer Andrews Barbara T. -

Arsenal Pulp Press Fonds (RBSC- ARC-1015)

University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections Finding Aid - Arsenal Pulp Press fonds (RBSC- ARC-1015) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.2.1 Printed: June 14, 2016 Language of description: English University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, 1961 East Mall Vancouver BC Canada V6T 1Z1 Telephone: 604-822-8208 Fax: 604-822-9587 http://www.library.ubc.ca/spcoll/ http://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca//index.php/arsenal-pulp-press-fonds Arsenal Pulp Press fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Series descriptions ........................................................................................................................................... 5 , Correspondence, [197-]-2009 .................................................................................................................... -

Uvic Torch Alumni Magazine • 2020 Autumn

Torch 2020 Autumn.qxp_Torch 20 Autumn 2020-11-03 11:24 AM Page 1 the University of Victoria Alumni Magazine AUTUMN 2020 TORCHUVIC BUILDING BRID GES UVic researchers and alumni are using creativity and skills to bridge gaps and help our community reach the other side of the pandemic. Antibody Aces | President in Profile | From Banker to Doctor Torch 2020 Autumn.qxp_Torch 20 Autumn 2020-11-03 11:24 AM Page 2 ON CAMPUS Inspiring Works The University of Victoria’sBFA graduate exhibition, normally held at the Visual Arts building, moved online this year due to the pandemic. The online catalogue, called Suggested Serving Size, features 29 graduating students working in a variety of contemporary disciplines. “Their collective drive and commitment to their disciplines—and each other— was inspiring and gave me great hope for the future,” says supervising professor and visual arts alumnus Richard Leong (BFA ’03). Find the online catalogue at: finearts.uvic.ca/visualarts/bfa/2020/ Lucy Gudewill, Chronic (2019, charcoal on paper) Georgia Tooke, Cooking with Bambi: King Kong Ding Dong Penis Enlarger Potion (2019, video still) Torch 2020 Autumn.qxp_Torch 20 Autumn 2020-11-03 11:24 AM Page 1 Jake Hrubizna, Float (2016, photograph) Cassidy Luteijn, Portrait of a Form 1–4 (2020, acrylic on canvas) Torch 2020 Autumn.qxp_Torch 20 Autumn 2020-11-03 11:24 AM Page 2 Table of Contents UVic Torch Alumni Magazine • Autumn 2020 UVic’s ALEXANDRE BROLO has partnered with ImmunoPrecise Antibodies. 17 Features 10 Goodbye, President Cassels 17 Antibody Aces A profile of the team at ImmunoPrecise Antibodies, a 14 Building Bridges company founded by a UVic alumnus. -

Bachelor of Arts Creative Writing Major

Full Program Proposal Bachelor of Arts Creative Writing Major Department of Creative Writing Faculty of Humanities Kwantlen Polytechnic University August 13, 2010 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ...........................................................................................1 II. Degree Content .................................................................................................4 III. Curriculum Design .......................................................................................... 15 IV. Program Delivery ............................................................................................ 16 V. Admission Requirements .............................................................................. 16 VI. Faculty .............................................................................................................. 18 VII. Program Resources ........................................................................................ 18 VIII Program Consultation .................................................................................... 20 Appendix A ..................................................................................................... 22 Appendix B ...................................................................................................... 23 Appendix C ...................................................................................................... 28 Appendix D ....................................................................................................