One Year Introduction to the New Testament [Lecture Notes]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek?

2 Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek? Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek? A Concise Compendium of the Many Internal and External Evidences of Aramaic Peshitta Primacy Publication Edition 1a, May 2008 Compiled by Raphael Christopher Lataster Edited by Ewan MacLeod Cover design by Stephen Meza © Copyright Raphael Christopher Lataster 2008 Foreword 3 Foreword A New and Powerful Tool in the Aramaic NT Primacy Movement Arises I wanted to set down a few words about my colleague and fellow Aramaicist Raphael Lataster, and his new book “Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek?” Having written two books on the subject myself, I can honestly say that there is no better free resource, both in terms of scope and level of detail, available on the Internet today. Much of the research that myself, Paul Younan and so many others have done is here, categorized conveniently by topic and issue. What Raphael though has also accomplished so expertly is to link these examples with a simple and unambiguous narrative style that leaves little doubt that the Peshitta Aramaic New Testament is in fact the original that Christians and Nazarene-Messianics have been searching for, for so long. The fact is, when Raphael decides to explore a topic, he is far from content in providing just a few examples and leaving the rest to the readers’ imagination. Instead, Raphael plumbs the depths of the Aramaic New Testament, and offers dozens of examples that speak to a particular type. Flip through the “split words” and “semi-split words” sections alone and you will see what I mean. -

St. Matthew the Apostle

Page 1 The Parish Community of St. Matthew the Apostle 81 Seymour Avenue, Edison, New Jersey 08817 | Phone: 732-985-5063 Website: stmatthewtheapostle.com | School Website: stmatthewtheapostle.com/school “Follow the Truth, not the crowd.” 6th Sunday of Easter - May 9, 2021 NOTICE: Ascension “Thursday” is Moved to Next Weekend For many years, most dioceses in the U.S. have celebrated the Feast of the Ascension on the 7th Sunday of Easter. The dioceses of New Jersey have not done this until last year because of Covid. The obligation to attend Mass on the traditional Ascension Thursday was therefore moved to the Sunday. This year again, the bishops of New Jersey (i.e. The Province of Newark) have agreed to transfer the feast to replace the Seventh Sunday of Easter. They will decide over the next few months whether this move would continue for future years. Currently, it only applies to this year. This coming Thursday would normally be that Holy Day of Obligation. But it is not a holy day, and we will only have the regularly-scheduled Mass at 8:30 AM which will be Thursday of the 6th Week of Easter (we will not do readings or Mass formulas for Ascension). You are not obligated to attend Mass on Thursday. Remember, during Covid, you are not required to attend Mass anyway. Parish Phone Numbers Mission Statement St. Matthew the Apostle Church is a diverse Roman Church ............................................ 732-985-5063 Fax .................................................. 732-985-9104 Catholic community empowered by the Spirit of God, School ............................................. 732-985-6633 formed by His Word, and nourished by the Eucharist. -

June 27, 2021

St. Matthew the Apostle Catholic Church Over 100 Years Founded in the “Ville” 1893 2715 North Sarah Street Saint Louis, Missouri 63113-2940 Office: (314) 531-6443 or (314) 531-6444 Fax: (314) 553-9268 Email Address: [email protected] Website: www.stmatthewtheapostle.org Office Hours: Monday—Friday 9 AM to 5 PM MASS SCHEDULE Sunday: 9:30 AM, St. Matthew Church Monday: 8:00 AM, Sts. Teresa & Bridget Rectory Tuesday-Wednesday: 8:00 AM, St. Matthew Rectory Thursday: 11:00 AM, St. Matthew Rectory Friday: 7:00 AM, Missionaries of Charity Chapel Saturday: 5:00 PM, St. Matthew Church Feast Days: 6:00 PM, St. Matthew Church RECONCILIATION By appointment only Parish Staff Parish Life Coordinator: Cheryl Archibald Pastoral Associate: Father Kevin Cullen, S.J. Founded 1893 Parish Secretary: Peg Murphy RCIA Coordinator: Cheryl Archibald Building the Kingdom of God Music Minister: Judith Jackson for over 125 Years in “The Ville” Youth and Young Adult Minister: Pam Mason Bookkeeper: Eric Thimsen Pastoral Council Jesuits in Residence Sheryl Williams, Chair Father Thomas Greene, S.J. Peter Jones, Vice Chair Father Daniel White, S.J. COMMUNITY HELP ORGANIZATIONS St. Vincent DePaul Society 2715 North Sarah Street 289-6101, mailbox 1169 Northside Youth & Senior Service Center 4120 Maffitt Ave. 531-4161 or 531-1937 St. Charles Lwanga Center 4746 Carter Ave. 367-7929 C. H. I. P. S. Health & Wellness Center 2431 North Grand Blvd. 652-9231 St. Louis Catholic Academy 4720 Carter Ave. 389-0401 Northside Community Housing 4067 Lincoln Ave. 534-5400 Stanley & Clayton Rice Family Center* 4145 Kennerly Ave. -

ST. MATTHEW the APOSTLE CHURCH June 27, 2021 | 13Th Sunday in Ordinary Time

ST. MATTHEW THE APOSTLE CHURCH June 27, 2021 | 13th Sunday In Ordinary Time 10021 JEFFERSON HWY | RIVER RIDGE, LA 70123 | [email protected] WWW.STMATTHEWTHEAPOSTLE.NET | 504.737.4537 504.737.2662 2 WEEKLY PRAYER Readings for the Week of June 27 2021 SUN 6/27 Wis 1:13-15; 2:23-24/Ps 30:2, 4, 5-6, 11, 12, 13 [2a]/2 Cor 8:7, 9, 13-15/Mk 5:21-43 or 5:21-24, 35b-43 MON 6/28 Gn18:16-33/Ps103:1b-2,3-4, 8-9, 10-11[8a]/Mt8:18-22 TUE 6/29 Vigil: Acts 3:1-10/Ps 19:2-3, 4-5 [5]/Gal 1:11-20/Jn 21:15-19; Day: Acts 12:1-11/Ps 34:2-3, 4-5, 6-7, 8-9 [5]/2 Tm 4:6-8, 17-18/Mt 16:13-19 WED 6/30 Gn21:5,8-20a/Ps34:7-8, 10-11, 12-13 [7a]/Mt 8:28-34 THU 7/01 Gn 22:1b-19/Ps 115:1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 8-9 [9]/Mt 9:1-8 FRI 7/02 Gn 23:1-4, 19; 24:1-8, 62-67/Ps 106:1b-2, 3-4a, 4b-5 [1b]/Mt 9:9-13 SAT 7/03 Eph 2:19-22/Ps 117:1bc, 2 [Mk 16:15]/Jn 20:24-29 SUN 7/04 Ez 2:2-5/Ps 123:1-2, 2, 3-4 [2cd]/2 Cor 12:7-10/Mk 6:1-6a Observances for the Week of June 27, 2021 Sunday: 13th Sunday in Ordinary Time Monday: St. -

Acts 11 PETER on HIS DEFENCE

The Acts based on Chuck Missler / William Barclay/Ray Steadman’s notes and commentary The Acts based on Chuck Missler / William Barclay/Ray Steadman’s notes and commentary Events Note: Est Phase Some dates shown are disputed Date Acts 11 Acts 1 Christ's Ascension 30 AD PETER ON HIS DEFENCE Acts 2 Pentecost: Peter's Sermon Acts 11:1-10 Acts 3 Lame Man Healed Birth of Acts 4 Persecution - Peter and John in Prison "The apostles and the brethren who were throughout Judaea heard the Acts 5 Saphira that the Gentiles too had received the word of God. So when Peter Church Angel Opens the Prison Doors for Peter an the came up to Jerusalem those of the circumcision criticized him Acts 5 other Apostles because, they said, `You went in to men who had never been Acts 6 7 Deacons Chosen circumcised and you ate with them.' So Peter began at the Acts 7 Stephen's Sermon and Stoning 35 AD beginning and told them the whole story. He said, `I was praying in the city of Joppa; in a trance I saw a vision. I saw a kind of vessel Acts 8 Simon Tries to Buy the Holy Spirit coming down like a great sheet let down by the four corners from Acts 8 Philip and the Ethipopian; Philip's Ministry heaven; and it came right down to me. I was gazing at it and trying Possibly Matthew @ Judea by Matthew the Apostle 37 AD to make out what it was and I saw on it the four-footed beasts of the 50 AD earth and the wild beasts and the creeping animals and the animals Acts 9 Saul (Paul) Converted on the Damascus Road that fly in the air. -

Fourth Sunday of Lent, March 26, 2017

Fourth Sunday of Lent, March 26,SUNDAY, 2017 MARCH 26, 2017 St. Gabriel the Archangel ——CATHOLIC CHURCH—— www.stgabrielstl.org Parish Mission Statement As St. Gabriel was sent by God to Mary, we also have been chosen to proclaim the Good News to our community today. Our mission is to bring all men and women together as people of God sharing the Bread of Life and living the Law of Love through service to all our neighbors. Like the First Christians, we also devote ourselves to: ♦ The instructions of the Apostles by reading Scripture, living the Gospel, and following the teachings of the bishop of Rome. St. Louis, MO 63109 ♦ The breaking of Bread through the celebration of the Eucharist and the Sacraments. ♦ Communal life as experienced through the celebration of the Eucharist and the Sacraments. ♦ Prayer to foster a personal relationship with God. We rely on the guidance of the Holy Spirit to “bring this good work to completion.” Masses Rosary Weekdays: 6:00am, 8:00am; Saturdays: 8:00am, Prayed weekdays at 6:40pm in the Church, on 5:00pm; Sundays: 6:30am, 9:00am, 11:00am, Saturdays at 4:30pm and each Thursday night at 6:00pm; Holy Days | Holidays: Check Bulletin 9:30pm under the cover of the driveway entrance outside of the Church. *St. Gabriel priests celebrate Mass at 11:00am on Tuesdays at the DuBourg House and at 11:00am Perpetual Help Devotions on Thursdays at Provision Living. Tuesdays after the 8:00am Mass and on the first Sacrament of Reconciliation Tuesday of the month at 7:30pm. -

April 22, 2020-Wednesday, Second Week of Easter Matthew the Apostle

April 22, 2020-Wednesday, Second Week of Easter Matthew the Apostle Matthew was a tax collector in Capernaum when Jesus called him to be a disciple. Mark and Luke call him Levi. Little is known about his life in the early Church. Tradition says he preached in Ethiopia, Parthia (modern-day Iran) and Persia, and that he was beheaded for his faith. His feast is September 21, and he is the patron saint of accountants. ******** Is Matthew the Apostle also Matthew the Evangelist? Early Christian tradition attached Matthew’s name to what is known as the “Gospel of Matthew.” However, since this Gospel appears to have been written sometime after 80 A.D., and uses a great deal of material from an earlier Gospel (that of Mark), biblical scholars think it unlikely that the author was an eyewitness of the events narrated. Toward the end of the first century, there was a tendency to attach the names of deceased apostles to various writings, because these writings preserved the apostolic tradition. I may be that the name of the apostle Matthew was given to this Gospel because it was written by someone who was part of an early Christian community evangelized by Matthew himself. ******** The Sunday Gospel readings during Cycle A (which are used this year) are generally taken from the Gospel of Matthew, especially during Ordinary Time. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ When Jesus had said this, he breathed on the disciples and said to them, “Receive the holy Spirit.” Jesus said to the disciples: “Whose sins you forgive are forgiven them, and whose sins you retain are retained.” (John 20:22-23) It is Easter Sunday evening, about 48 hours after Jesus’ death on the cross. -

ST. MATTHEW the APOSTLE CHURCH June 20, 2021 | 12Th Sunday in Ordinary Time 2

ST. MATTHEW THE APOSTLE CHURCH June 20, 2021 | 12th Sunday In Ordinary Time 2 WEEKLY PRAYER Readings for the Week of June 20 2021 SUN 6/20 Jb 38:1, 8-11/ Ps 107:23-24, 25-26, 28-29, 30-31 [1b]/2 Cor 5:14-17/Mk 4:35-41 MON 6/21 Gn12:1-9/Ps 33:12-13, 18-19, 20 and 22 [12]/Mt 7:1-5 TUE 6/22 Gn 13:2, 5-18/Ps 15:2-3a, 3bc-4ab,5[1b]/Mt 7:6,12-14 WED 6/23 Gn 15:1-12, 17-18/Ps 105:1-2, 3-4, 6-7, 8-9 [8a]/Mt 7:15-20 THU 6/24 Vigil: Jer 1:4-10/Ps 71:1-2, 3-4,5-6,15,17[6b]/1Pt1:8- 12/Lk 1:5-17; Day: Is 49:1-6/Ps 139:1-3, 13-14, 14-15 [14a]/Acts 13:22-26/Lk 1:57-66, 80 FRI 6/25 Gn 17:1, 9-10, 15-22/Ps 128:1-2, 3, 4-5 [4]/Mt 8:1-4 SAT 6/26 Gn 18:1-15/Lk 1:46-47, 48-49, 50 and 53, 54-55 [cf. 54b]/Mt 8:5-17 SUN 6/27 Wis 1:13-15; 2:23-24/Ps 30:2, 4, 5-6, 11, 12, 13 [2a]/2 Cor 8:7, 9, 13-15/Mk 5:21-43 or 5:21-24, 35b-43 Observances for the Week of June 20, 2021 Sunday: 12th Sunday in Ordinary Time/Father’s Day Monday: St. -

Matthew - John Schultz © - Bible-Commentaries.Com

Matthew - John Schultz © - Bible-Commentaries.com MATTHEUS’ GOSPEL I. Author: According to The New Unger’s Bible Dictionary the name Matthew is a contraction of Mattathias, meaning: “gift of Jehovah.” The son of a certain Alphaeus surnamed Levi (Mark 2:14; Luke 5:27). It is not known whether his father was the same as the Alphaeus named as the father of James the Less, but he was probably another.” Matthew calls himself Matthew in telling the story of his call in this Gospel.1 Both Mark and Luke introduce Matthew to us as a tax collector by the name of Levi. Mark identifies him as “Levi son of Alphaeus.”2 All three Gospel record Jesus’ words: “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.”3 Nelson’s Bible Dictionary observes: “Matthew is an anonymous gospel. Like other gospel titles, the title was added in the second century A.D. and reflects the tradition of a later time. How, then, did the gospel acquire its name? Writing about A.D. 130, Papias, bishop of Hierapolis in Asia Minor (modern Turkey), records, ‘Matthew collected the oracles in the Hebrew (that is, Aramaic) language, and each interpreted them as best he could.’ Until comparative studies of the gospels in modern times, the church understood ‘oracles’ to refer to the first gospel and considered Matthew, the apostle and former tax collector (9:9; 10:3), to be the author. This conclusion, however, is full of problems. Our Gospel of Matthew is written in Greek, not Aramaic (as Papias records); and no copy of an Aramaic original of the gospel has ever been found. -

June 28, 2015

JUNE 28, 2015 1 Survey of the New Testament (Abide Conference Series) Copyright © 2015 by Crossing Church of Bardstown, Inc. CrossingBardstown.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by USA copyright law. Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, maps and map captions are provided by The ESV Study Bible™ copyright © 2008 by Crossway Bibles, Wheaton, Illinois. 2 Introduction What is it? The New Testament is a collection of writings produced by the early church to recount the life and teachings of Jesus and give instructions on how to live as the church of Jesus Christ. Like the Old Testament, men were inspired by God to write what is contained in these writings (2 Timothy 3:16, 2 Peter 1:1921). The New Testament is God’s word to us. Canon Question Why did these books make it in? Weren’t there other writings? (Gospel of Thomas, Judas, etc?) Criteria of inclusion: ● rule of faith: does the book correspond to the teaching of the church? ● Apostolicity: by an apostle or one who was close to one ● Universality: it was being used everywhere Structure The Story of Jesus:Gospels The Story of the Church: Acts The Teaching of the Church: Letters of Paul General Epistles Revelation What happened between Old and New Testaments? 539331 BC The Persian Period (Esther) 331164 BC The Hellenistic Period (Alexander the Great) 164163 BC The Hasmonean (Maccabean) Period (Judas Maccabaeus) 63 BC 135 AD The Roman Period (Pompey, Caesars, etc) The shifts in Judaism: When sacrifices and temple worship became impossible, obedience to the law became central. -

Team Map.Indd

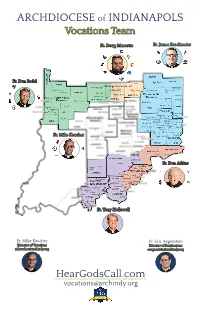

ARCHDIOCESE of INDIANAPOLS VVocationsocations TTeameam FFr.r. DDougoug MMarcottearcotte FFr.r. JamesJames BBrockmeierrockmeier FFr.r. DanDan BedelBedel FFr.r. MikeMike KeucherKeucher FFr.r. DDanan AAtkinstkins FFr.r. TTonyony HHollowellollowell Fr. Mike Keucher Fr. Eric Augenstein DDirectorirector ooff VVocationsocations DDirectorirector ofof SeminariansSeminarians [email protected]@archindy.org [email protected]@archindy.org HearGodsCall.com [email protected] Fr. Dan Atkins Fr. Dan Bedel Fr. James Brockmeier Fr. Mike Keucher Fr. Doug Marcotte Parishes - New Albany Deanery Parishes - Terre Haute Deanery Parishes - Connersville Deanery Parishes - Batesville Deanery Parishes - Indianapolis North Deanery St. Michael, Charlestown Annunciation, Brazil St. Elizabeth of Hungary, Cambridge St. Vincent de Paul, Shelby County Immaculate Heart of Mary, Indianapolis St. Anthony of Padua, Clarksville Sacred Heart, Clinton City St. Joseph, Shelbyville Christ the King, Indianapolis St. Joseph, Corydon St. Paul the Apostle, Greencastle St. Gabriel, Connersville St. Andrew the Apostle, Indy St. Michael, Greenville St. Joseph, Rockville St. Bridget, Liberty Parishes - Bloomington Deanery St. Joan of Arc, Indianapolis St. Mary-of-the-Knobs, Floyds Knobs St. Mary-of-the-Woods, St. Mary-of- St. Anne, New Castle St. Vincent de Paul, Bedford St. Lawrence, Indianapolis St. Bernard, Frenchtown the-Woods St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, Richmond St. Charles Borromeo, Bloomington St. Luke the Evangelist, Indy St. Francis Xavier, Henryville Sacred Heart of Jesus, Terre Haute St. Mary (Immaculate Conception), St. John the Apostle, Bloomington St. Matthew the Apostle, Indy Sacred Heart of Jesus, Most, St. Benedict, Terre Haute Rushville St. Paul Catholic Center, Bloomington St. Pius X, Indianapolis Jeffersonville St. Joseph University Parish, Terre St. Martin of Tours, Martinsville St. -

Feast of St. Matthew by Fr. Rick This Morning I Want to Engage Your

Feast of St. Matthew By Fr. Rick This morning I want to engage your imagination. I want you to imagine a United States different from the one in which we currently live. Imagine our country as having been overrun by another world power and we live in subjection to that world power. It is an oppressive situation for us especially with regard to something I daresay we all treasure – freedom of speech. This world power demands of us considerable taxes which are not generally spent on services and programs for our benefit as a people. And there is no explanation given to us of how the monies are spent – transparency is not the practice of this oppressive world power. Now let’s say that there are some American citizens who, oddly enough, benefit from this oppression we feel as a people. Certainly there are collaborators at a governing level – citizens in leadership positions appointed by this foreign power to ensure no one rocks the boat. In the best practice of political-ease, they encourage us to see the benefit of the situation by saying it could be worse. But there are others who are not at this high level of leadership, yet they still benefit from our oppression. These people collect the taxes that the world power requires of us. Not only do they collect the taxes, they add a service charge for their own salary because the world power doesn’t pay them. Some of these people live in very, very nice houses and drive the most elegant upper-end automobiles.