PDF | 772.82 KB | English Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Illegal Excavation and Trade of Syrian Cultural Objects

JOURNAL OF FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY, 2018 VOL. 43, NO. 1, 74–84 https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2017.1410919 The Illegal Excavation and Trade of Syrian Cultural Objects: A View from the Ground Neil Brodiea and Isber Sabrineb aUniversity of Oxford, Oxford, UK; bUniversitat de Girona, Girona, Spain ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The illegal excavation and trade of cultural objects from Syrian archaeological sites worsened Syria; looting; cultural markedly after the outbreak of civil disturbance and conflict in 2011. Since then, the damage to objects; coins; policy archaeological heritage has been well documented, and the issue of terrorist funding explored, but hardly any research has been conducted into the organization and operation of theft and trafficking of cultural objects inside Syria. As a first step in that direction, this paper presents texts of interviews with seven people resident in Syria who have first-hand knowledge of the trade, and uses information they provided to suggest a model of socioeconomic organization of the Syrian war economy regarding the trafficking of cultural objects. It highlights the importance of coins and other small objects for trade, and concludes by considering what lessons might be drawn from this model to improve presently established public policy. Introduction conflictantiquities.wordpress.com/). Nevertheless, most of what is known about illegal excavation and trade inside Like that of many countries in the Middle East and North Syria comes from some of the better media reporting, Africa (MENA) region, for the past few decades the archaeo- which has on occasion managed to access people with first- logical heritage of Syria has been robbed of cultural objects for hand knowledge or experience of the problem. -

S/2019/321 Security Council

United Nations S/2019/321 Security Council Distr.: General 16 April 2019 Original: English Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018) and 2449 (2018) Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is the sixtieth submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), paragraph 10 of resolution 2165 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2191 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2258 (2015), paragraph 5 of resolution 2332 (2016), paragraph 6 of resolution 2393 (2017),paragraph 12 of resolution 2401 (2018) and paragraph 6 of resolution 2449 (2018), in the last of which the Council requested the Secretary-General to provide a report at least every 60 days, on the implementation of the resolutions by all parties to the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The information contained herein is based on data available to agencies of the United Nations system and obtained from the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and other relevant sources. Data from agencies of the United Nations system on their humanitarian deliveries have been reported for February and March 2019. II. Major developments Box 1 Key points: February and March 2019 1. Large numbers of civilians were reportedly killed and injured in Baghuz and surrounding areas in south-eastern Dayr al-Zawr Governorate as a result of air strikes and intense fighting between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. From 4 December 2018 through the end of March 2019, more than 63,500 people were displaced out of the area to the Hawl camp in Hasakah Governorate. -

Covid-19: Tool of Conflict Or Opportunity for Local Peace in Northwest Syria

Supported by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Covid Collective is based at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). Research Report July 2021 C ovid-19: Tool of Conflict or Opportunity for Local Peace in Northwest Syria? © Baraa Obied Juline Beaujouan Political Settlements Research Programme (PSRP) at the University of Edinburgh Acknowledgements This research is an output from the Political Settlements Research Programme (PSRP), a partner in the Covid Collective. Supported by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Covid Collective is based at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). The Collective brings together the expertise of UK and Southern-based research partner organisations and offers a rapid social science research response to inform decision-making on some of the most pressing Covid-19 related development challenges. Opinions stated in this brief are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Covid Collective, its partners, or FCDO. Any use of this work should acknowledge the author and the Political Settlements Research Programme. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the PSRP website. Thanks are due to Christine Bell for peer review and editorial advice, and to Eyas Ghreiz and Abdulah El hafi for collaborating on the study and offering feedback on various versions of the draft. Thanks to Harriet Cornell for editing and production work. Thanks to the Blue Team and Civilization Team for illustrating the report with original artwork. The author hereby thanks all the people who took the time to participate in this study and all the collaborators who contributed to this project. -

Syria Market Monitoring Exercise Cash-Based Responses Snapshot: 16-23 October 2017 Technical Working Group

Syria Market Monitoring Exercise Cash-Based Responses Snapshot: 16-23 October 2017 Technical Working Group KEY FINDINGS OVERVIEW • The most significant trend was the near currencies decreased this month, which • To inform humanitarian actors’ cash and voucher Syrian household for one month. doubling of SMEB costs in besieged areas. resulted in decreasing prices of several programming, REACH and the Cash-Based • Between 16 and 23 October 2017, a network While SMEB data collected was incomplete assessed items. The median exchange rates Responses Technical Working Group (CBR– of 12 NGOs involved in cash-based responses due to shortages and consequently the paucity for USD/SYP decreased by 10%, TRY/SYP by TWG) conduct monthly monitoring of key markets in Syria (CARE/Shafak, Concern, Danish of price data, the sudden increase in the price 10%, and JOD/SYP by 5% across assessed throughout Syria to assess the availability and Church Aid, GOAL, IRC, Mercy Corps, People of key items in the past month is evident. areas. affordability of basic commodities. in Need, REACH, Save the Children, Solidarités • The shortages of chicken and potatoes • SMEB cost changes greater than 10% were • Monitored commodities reflect those that are International and Violet) contributed data from 72 continued in multiple communities in Eastern observed in 11 of the 50 subdistricts with typically available, sold in markets and consumed subdistricts spanning 11 governorates. For Ghouta, with additional shortage of eggs and comparable data between September and by an average Syrian household including food coverage, see the map on the left. milk in Arbin. In addition, LPG continues to be October. -

Security Council Distr.: General 24 August 2016

United Nations S/2016/738/Rev.1 Security Council Distr.: General 24 August 2016 Original: English Letter dated 24 August 2016 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to convey herewith the third report of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism. I should be grateful if the present letter and the report could be brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council. (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 16-14878 (E) 140916 *1614878* S/2016/738/Rev.1 Letter dated 24 August 2016 from the Leadership Panel of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons- United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism addressed to the Secretary-General The Leadership Panel of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism has the honour to transmit the Mechanism’s third report pursuant to Security Council resolution 2235 (2015). The report provides an update on the activities of the Mechanism up to 19 August 2016. It also outlines the concluding assessments of the Leadership Panel to date, on the basis of the results of the investigation into the nine selected cases of the use of chemicals as weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic. The Leadership Panel wishes to thank the Secretary-General for the confidence placed in it. The Panel appreciates the indispensable support provided by the Secretariat, including the Office for Disarmament Affairs, the Department for Political Affairs and the Office of Legal Affairs, and the United Nations officials who have assisted the Mechanism in New York, Geneva and Damascus. -

S/PV.8449 the Situation in the Middle East, Including the Palestinian Question 22/01/2019

United Nations S/ PV.8449 Security Council Provisional Seventy-fourth year 8449th meeting Tuesday, 22 January 2019, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Singer Weisinger/Mr. Trullols ................... (Dominican Republic) Members: Belgium ....................................... Mr. Pecsteen de Buytswerve China ......................................... Mr. Ma Zhaoxu Côte d’Ivoire ................................... Mr. Ipo Equatorial Guinea ............................... Mr. Ndong Mba France ........................................ Mr. Delattre Germany ...................................... Mr. Heusgen Indonesia. Mrs. Marsudi Kuwait ........................................ Mr. Alotaibi Peru .......................................... Mr. Meza-Cuadra Poland ........................................ Ms. Wronecka Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Nebenzia South Africa ................................... Mr. Matjila United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Ms. Pierce United States of America .......................... Mr. Cohen Agenda The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question . This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting Service, room U-0506 ([email protected]). Corrected records will be reissued electronically on the Official Document System of the United Nations (http://documents.un.org). 19-01678 (E) *1901678* S/PV.8449 The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question 22/01/2019 The meeting was called to order at 10.05 a.m. with the provisional rules of procedure and previous practice in this regard. Expression of sympathy in connection with and There being no objection, it is so decided. -

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001 Weekly Report 2 — August 18, 2014 Michael D. Danti Heritage Timeline August 16 APSA website released a video and a short report on alleged looting at Deir Turmanin (5th Century AD) in Idlib Governate. SHI Incident Report SHI14-018. • DGAM posted a report on alleged vandalism/looting and combat damage sustained to the Roman/Byzantine Beit Hariri (var. Zain al-Abdeen Palace) of the 2nd Century AD in Inkhil, Daraa Governate. SHI Incident Report SHI14-017. • Heritage for Peace released its weekly report Damage to Syria’s Heritage 17 August 2014. August 15 DGAM posts short report Burning of the Historic Noria Gaabariyya in Hama. Cf. SHI Incident Report SHI14-006 dated Aug. 9. DGAM report provides new photos of the fire damage. SHI Report Update SHI14-006. August 14 Chasing Aphrodite website posted an article entitled Twenty Percent: ISIS “Khums” Tax on Archaeological Loot Fuels the Conflicts in Syria and Iraq featuring an interview between CA’s Jason Felch and Dr. Amr al-Azm of Shawnee State University. • Damage to a 6th century mosaic from al-Firkiya in the Maarat al-Numaan Museum. Source: Smithsonian Newsdesk report. SHI Incident Report SHI14-016. • Aleppo Archaeology website posted a video showing damage in the area south of the Aleppo Citadel — much of the damage was caused by the July 29 tunnel bombing of the Serail by the Islamic Front. https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?v=739634902761700&set=vb.4596681774 25042&type=2&theater SHI Incident Report Update SHI14-004. -

EUI RSCAS Working Paper 2021/08 How Global Jihad Relocalises And

RSC 2021/08 Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Middle East Directions Programme How Global Jihad Relocalises and Where it Leads. The Case of HTS, the Former AQ Franchise in Syria Jerome Drevon and Patrick Haenni European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Middle East Directions Programm How Global Jihad Relocalises and Where it Leads. The Case of HTS, the Former AQ Franchise in Syria Jerome Drevon and Patrick Haenni EUI Working Paper RSC 2021/08 Terms of access and reuse for this work are governed by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC- BY 4.0) International license. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper series and number, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © Jerome Drevon and Patrick Haenni, 2021 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY 4.0) International license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Published in January 2021 by the European University Institute. Badia Fiesolana, via dei Roccettini 9 I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual author(s) and not those of the European University Institute. This publication is available in Open Access in Cadmus, the EUI Research Repository: https://cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. -

UK Home Office

Country Policy and Information Note Syria: the Syrian Civil War Version 4.0 August 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

“Targeting Life in Idlib”

HUMAN RIGHTS “Targeting Life in Idlib” WATCH Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Copyright © 2020 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: https://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Map .................................................................................................................................. i Glossary .......................................................................................................................... ii Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

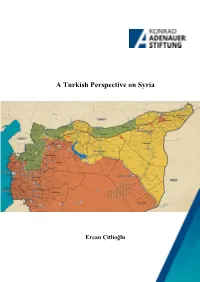

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

Army Overruns Idlib Crossroads Town Despite Turkey's Warnings

7 International Sunday, February 9, 2020 Army overruns Idlib crossroads town despite Turkey’s warnings Syrian forces press a blistering assault with Russian support DAMASCUS: The Syrian army took control of the strate- gic northwestern crossroads town of Saraqeb yesterday in the latest gain of a weeks-long offensive against the country’s last major rebel bastion of Idlib. The advance came shortly after Turkey sent additional troops into the African leaders region and threatened to respond if any of its military observation posts in Idlib, set up under a 2018 truce, grapple with failure come under attack. “Army units now exercise full control over the town of to ‘silence the guns’ Saraqeb,” state television reported, over footage of the town’s streets, deserted after weeks of bombardment. Since December, government forces have pressed a blis- ADDIS ABABA: Seven years ago, amid extravagant tering assault against the Idlib region with Russian sup- celebrations marking the African Union’s 50th port, retaking town after town despite warnings from anniversary, the continent’s heads of state declared rebel ally Turkey to back off. The violence has killed more they would “end all wars in Africa by 2020.” But as than 300 civilians and sent some 586,000 fleeing civil- leaders travel to Addis Ababa this weekend for the lat- ians onto the roads, seeking relative safety nearer the est summit of the 55-member bloc - organized under Turkish border the theme “Silencing the Guns” — there is little ques- The United Nations and aid groups have appealed for tion they are doomed to fall well short of their goal.