Analisi Architettonica Del Castello Di Himeji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

Watanabe, Tokyo, E

Edition Axel Menges GmbH Esslinger Straße 24 D-70736 Stuttgart-Fellbach tel. +49-711-574759 fax +49-711-574784 Hiroshi Watanabe The Architecture of Tokyo 348 pp. with 330 ill., 161,5 x 222 mm, soft-cover, English ISBN 3-930698-93-5 Euro 36.00, sfr 62.00, £ 24.00, US $ 42.00, $A 68.00 The Tokyo region is the most populous metropolitan area in the world and a place of extraordinary vitality. The political, economic and cultural centre of Japan, Tokyo also exerts an enormous inter- national influence. In fact the region has been pivotal to the nation’s affairs for centuries. Its sheer size, its concentration of resources and institutions and its long history have produced buildings of many different types from many different eras. Distributors This is the first guide to introduce in one volume the architec- ture of the Tokyo region, encompassing Tokyo proper and adja- Brockhaus Commission cent prefectures, in all its remarkable variety. The buildings are pre- Kreidlerstraße 9 sented chronologically and grouped into six periods: the medieval D-70806 Kornwestheim period (1185–1600), the Edo period (1600–1868), the Meiji period Germany (1868–1912), the Taisho and early Showa period (1912–1945), the tel. +49-7154-1327-33 postwar reconstruction period (1945–1970) and the contemporary fax +49-7154-1327-13 period (1970 until today). This comprehensive coverage permits [email protected] those interested in Japanese architecture or culture to focus on a particular era or to examine buildings within a larger temporal Buchzentrum AG framework. A concise discussion of the history of the region and Industriestraße Ost 10 the architecture of Japan develops a context within which the indi- CH-4614 Hägendorf vidual works may be viewed. -

Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art, 1600-2005

japanese art | religions graham FAITH AND POWER IN JAPANESE BUDDHIST ART, 1600–2005 Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art explores the transformation of Buddhism from the premodern to the contemporary era in Japan and the central role its visual culture has played in this transformation. The chapters elucidate the thread of change over time in the practice of Bud- dhism as revealed in sites of devotion and in imagery representing the FAITH AND POWER religion’s most popular deities and religious practices. It also introduces the work of modern and contemporary artists who are not generally as- sociated with institutional Buddhism but whose faith inspires their art. IN JAPANESE BUDDHIST ART The author makes a persuasive argument that the neglect of these ma- terials by scholars results from erroneous presumptions about the aes- thetic superiority of early Japanese Buddhist artifacts and an asserted 160 0 – 20 05 decline in the institutional power of the religion after the sixteenth century. She demonstrates that recent works constitute a significant contribution to the history of Japanese art and architecture, providing evidence of Buddhism’s persistent and compelling presence at all levels of Japanese society. The book is divided into two chronological sections. The first explores Buddhism in an earlier period of Japanese art (1600–1868), emphasiz- ing the production of Buddhist temples and imagery within the larger political, social, and economic concerns of the time. The second section addresses Buddhism’s visual culture in modern Japan (1868–2005), specifically the relationship between Buddhist institutions prior to World War II and the increasingly militaristic national government that had initially persecuted them. -

Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: the Significance of “Women’S Art” in Early Modern Japan

Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gregory P. A. Levine, Chair Professor Patricia Berger Professor H. Mack Horton Fall 2010 Copyright by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto 2010. All rights reserved. Abstract Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Gregory Levine, Chair This dissertation focuses on the visual and material culture of Hōkyōji Imperial Buddhist Convent (Hōkyōji ama monzeki jiin) during the Edo period (1600-1868). Situated in Kyoto and in operation since the mid-fourteenth century, Hōkyōji has been the home for women from the highest echelons of society—the nobility and military aristocracy—since its foundation. The objects associated with women in the rarefied position of princess-nun offer an invaluable look into the role of visual and material culture in the lives of elite women in early modern Japan. Art associated with nuns reflects aristocratic upbringing, religious devotion, and individual expression. As such, it defies easy classification: court, convent, sacred, secular, elite, and female are shown to be inadequate labels to identify art associated with women. This study examines visual and material culture through the intersecting factors that inspired, affected, and defined the lives of princess-nuns, broadening the understanding of the significance of art associated with women in Japanese art history. -

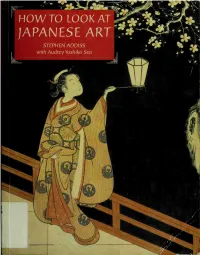

How to Look at Japanese Art I

HOWTO LOOKAT lAPANESE ART STEPHEN ADDISS with Audrey Yos hi ko Seo lu mgBf 1 mi 1 Aim [ t ^ ' . .. J ' " " n* HOW TO LOOK AT JAPANESE ART I Stephen Addi'ss H with a chapter on gardens by H Audrey Yoshiko Seo Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers ALLSTON BRANCH LIBRARY , To Joseph Seuhert Moore Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Addiss, Stephen, 1935- How to look at Japanese art / Stephen Addiss with a chapter on Carnes gardens by Audrey Yoshiko Seo. Lee p. cm. “Ceramics, sculpture and traditional Buddhist art, secular and Zen painting, calligraphy, woodblock prints, gardens.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-8109-2640-7 (pbk.) 1. Art, Japanese. I. Seo, Audrey Yoshiko. II. Title N7350.A375 1996 709' .52— dc20 95-21879 Front cover: Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770), Girl Viewing Plum Blossoms at Night (see hgure 50) Back cover, from left to right, above: Ko-kutani Platter, 17th cen- tury (see hgure 7); Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875), Sencha Teapot (see hgure 46); Fudo Myoo, c. 839 (see hgure 18). Below: Ryo-gin- tei (Dragon Song Garden), Kyoto, 1964 (see hgure 63). Back- ground: Page of calligraphy from the Ishiyama-gire early 12th century (see hgure 38) On the title page: Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858), Yokkaichi (see hgure 55) Text copyright © 1996 Stephen Addiss Gardens text copyright © 1996 Audrey Yoshiko Seo Illustrations copyright © 1996 Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Published in 1996 by Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, New York All rights reserv'ed. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher Printed and bound in Japan CONTENTS Acknowledgments 6 Introduction 7 Outline of Japanese Historical Periods 12 Pronunciation Guide 13 1. -

The Akamon of the Kaga Mansion and Daimyō Gateway Architecture in Edo1

AUTOR INVITADO Mirai. Estudios Japoneses ISSN-e: 1988-2378 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/MIRA.57100 Painting the town red: The Akamon of the Kaga mansion and daimyō gateway architecture in Edo1 William H. Coaldrake2 Abstract: Built in 1827 to commemorate the marriage of the daimyō Maeda Nariyasu to a daughter of the shogun Tokugawa Ienari, the Akamon or ‘Red Gateway’ of the University of Tokyo, is generally claimed to be a unique gateway because of its distinctive colour and architectural style. This article uses an inter- disciplinary methodology, drawing on architectural history, law and art history, to refute this view of the Akamon. It analyses and accounts for the architectural form of the gateway and its ancillary guard houses (bansho) by examining Tokugawa bakufu architectural regulations (oboegaki) and the depiction of daimyō gateways in doro-e and ukiyo-e. It concludes that there were close similarities between the Akamon and the gateways of high ranking daimyō in Edo. This similarity includes the red paint, which, it turns out, was not limited to shogunal bridal gateways but was in more general use by daimyō for their own gateways by the end of the Edo period. Indeed, the Akamon was called the ‘red gateway’ only from the 1880s after the many other red gateways had disappeared following the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate. The expression ‘to paint the town red’ refers not only to the way the Akamon celebrated the marriage of Yōhime, but also more broadly to characterize the way many of the other gateways at daimyō mansions in the central sectors of Edo had entrances that were decorated with bright red paint. -

Diss Master Draft-Pdf

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Visual and Material Culture at Hokyoji Imperial Convent: The Significance of "Women's Art" in Early Modern Japan Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8fq6n1qb Author Yamamoto, Sharon Mitsuko Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gregory P. A. Levine, Chair Professor Patricia Berger Professor H. Mack Horton Fall 2010 Copyright by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto 2010. All rights reserved. Abstract Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Gregory Levine, Chair This dissertation focuses on the visual and material culture of Hōkyōji Imperial Buddhist Convent (Hōkyōji ama monzeki jiin) during the Edo period (1600-1868). Situated in Kyoto and in operation since the mid-fourteenth century, Hōkyōji has been the home for women from the highest echelons of society—the nobility and military aristocracy—since its foundation. The objects associated with women in the rarefied position of princess-nun offer an invaluable look into the role of visual and material culture in the lives of elite women in early modern Japan. -

Roof Typology and Composition in Traditional Japanese Architecture

Roof Typology and Composition in Traditional Japanese Architecture I Introduction…………………………………………………………………...1 II Basic Roof Forms, Structures and Materials………………………………….3 II.1 Basic Roof Forms II.1.1 Kirizuma, Yosemune and Irimoya II.1.2 Combined Roofs II.1.3 Gable Entered (tsuma-iri) and Side Entered (hira-iri) II.2 Roof Trusses II.2.1 Sasu-gumi II.2.2 Wagoya II.2.3 Shintsuka-gumi II.2.4 Noboribari-gumi II.2.5 Combined Systems II.3 Roofing Materials II.3.1 Tile II.3.2 Thatch II.3.3 Wood: Planks, Shingle and Bark III Traditional Japanese Architecture III.1 Prehistoric and Antique Architecture………..………………………………11 III.1.1 Tateana Jukyo III.1.2 Takayuka Jukyo III.1.3 Nara Period Residences III.1.4 Menkiho III.2 Shinto Shrines……………………………………………………………….18 III.2.1 Shimei, Taisha and Sumiyoshi Styles III.2.2 Nagare and Kasuga Styles III.2.3 Later Styles III.3 Aristocrats’ Houses………………………………………………………….25 III.3.1 Shinden Style III.3.2 Shoin Style III.4 Common People Houses: Minka…………………………………………….29 III.4.1 Structure III.4.2 Type of Spaces III.4.3 Plan Evolution III.4.4 Building Restrictions III.4.5 Diversity of Styles III.4.5.1.1 City Dwellings, machiya III.4.5.1.2 Farmers’ Single Ridge Style Houses III.4.5.1.3 Farmers’ Bunto Style Houses III.4.5.1.4 Farmers’ Multiple Ridges Style Houses IV Relation Between Different Functional Spaces and the Roof Form………….48 IV.1 Type 1 ……………………………………………………………………..50 IV.2 Type 2 ……………………………………………………………………..67 IV.3 Type 3 ……………………………………………………………………..80 V The Hierarchy Between Functionally Different Spaces Expressed Trough the Roof Design………………………………………………………………….109 VI Conclusion……………………………………………………………..…….119 I- Introduction The purpose of this study is to analyze the typology and the composition of the roofs in Japanese traditional architecture. -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN FALL-WINTER, 2004 Naritasan

EARLY MODERN JAPAN FALL-WINTER, 2004 Naritasan Shinshōji and Common- ment of numerous branch temples throughout Ja- pan, where worshippers offer their prayers to Fudō er Patronage During the Edo Pe- Myōō's empowered replicas.3 Today, getting to riod Naritasan is an easy train ride of an hour or so ©Patricia J. Graham from the city, but during the Edo period, the forty- three mile (seventy kilometer) distance took two University of Kansas 4 days and one night of travel by foot and boat. The Shingon temple of Naritasan Shinshōji 成 Nevertheless, even then it attracted large numbers of visitors, mostly commoners from the city of 田山新勝寺 (popularly known as "Naritasan") is Edo, who sought practical benefits from the tem- a sprawling religious complex located close to ple's illustrious main deity and an opportunity for Narita Airport outside Tokyo. Along with the a short vacation in the countryside away from the Meiji Shrine 明治神宮 and Kawasaki Daishi congested urban environs. 川崎大師, it is one of Japan's three most visited My focus here is to illuminate the strength of religious sites during the New Year's season. Not motivations for, and manifestations of Buddhist coincidentally, all three are located in and around patronage at Naritasan by commoners from the Tokyo, Japan's most populous urban center. Nari- nearby metropolis of Edo, throughout the Edo pe- tasan's main object of worship is Fudō Myōō (Skt: riod. The tangible results of commoner devotion Acalanātha) 不動明王, one of the five Buddhist primarily take the form of a fine group of well Wisdom Kings (Godai Myōō 五大明王).1 In re- preserved buildings and numerous artifacts do- cent decades, this statue of Fudō has become so nated to the temple, both by Edo luminaries and associated with its ability to ensure devotees' anonymous Edo era townspeople. -

![OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENTPRINTING AGENCY | Ein^LJSH ^TON ] Bg*Q-+-^-B-L! H+B %'B.M.Wwtoim](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3202/official-gazette-governmentprinting-agency-ein-ljsh-ton-bg-q-b-l-h-b-b-m-wwtoim-2983202.webp)

OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENTPRINTING AGENCY | Ein^LJSH ^TON ] Bg*Q-+-^-B-L! H+B %'B.M.Wwtoim

OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENTPRINTING AGENCY | EiN^LJSH ^TON ] Bg*Q-+-^-b-l! H+B %'B.m.WWtoim EXTRA No. 103 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 7, 1951 PUBLIC NOTICES PRIME MINISTER'S OFFICE Public Notice of Screening Result No. 51 (Nov. 1-Nov. 30, 1951) December 7, 1951 Director of Cabinet Secretariat OKAZAKI Katsuo 1. This table shows the screening result made by the Prime Minister in accordance with the Impe- rial Ordinance concerning the Exclusion, Retirement, Etc. from Public Offices (Imperial Ordinance No. 1 of 1947), Ordinance concerning the Enforcement of Imperial Ordinance No. 1 of 1947 (Cabinet and Home Ministry Ordinance Nj. 1 of 1947) and provisions of Cabinet Order No. 62 of 1948. 2. This table is to be most widely made public. The office of a city, ward, town or village shall, when receiving this ojficial reports, placard the very table. This table shall, at least, be placarded for month, and it shall, upon the next official report being received, be replaced by a new one. The old report replaced, shall not be destroyed, and be preserved after binding at the office of the city, ward, town or village, to make it possible for public perusal. 3. The Questionnaires of the persons who were published on this table and of whom the screening has been completed may be offered for public perusal at the Supervision Section of the Cabinet Secretariat or of the Offices of the Prefectures concerned. Any one may, freely peruse Questionnaires of the preceding paragraph by his request. 4. Result (1) Number of persons subjected to screening: 7,397 persons 1) Persons decided not coming under the Memorandum: 5,791 persons (A) Persons Scheduled to be Appointed or Promoted Public Offices and Names of Persons to be Newly Appointed Secretaries of the Court ASAI Kiyoo ANANO Kenji. -

Primula Sieboldii: Visiting and Growing Sakurasoh, by Paul Held 19

ROCK GARDEN ^^S^OrT QUARTERLY VOLUME 55 NUMBER 1 WINTER 1997 COVER: Oenothera caespitosa at dusk, by Dick Van Reyper All Material Copyright © 1997 North American Rock Garden Society Printed by AgPress, 1531 Yuma Street, Manhattan, Kansas 66502 ROCK GARDEN QUARTERLY BULLETIN OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ROCK GARDEN SOCIETY formerly Bulletin of the American Rock Garden Society VOLUME 55 NUMBER 1 WINTER 1997 FEATURES Living Souvenirs: An Urban Horticultural Expedition to Japan, by Carole P. Smith 3 Primula sieboldii: Visiting and Growing Sakurasoh, by Paul Held 19 Paradise Regained: South Africa in Late Summer, by Panayoti Kelaidis 31 Erythroniums: Naturalizing with the Best, by William A. Dale 47 Geographical Names: European Plants, Geoffrey Charlesworth 53 Gentiana scabra: Musings from a Rock Garden, by Alexej Borkovec 60 Phyllodoce: A Supra-Sphagnum Way of Growing, by Phil Zimmerman 63 2 ROCK GARDEN QUARTERLY VOL. 55(1) LIVING SOUVENIRS: AN URBAN EXPEDITION TO JAPAN by Carole P. Smith AA^hat is the best way to satisfy I might visit. Forty-five letters were all your gardening yens in a foreign sent, and I expected to receive five or country—if you want to explore the six replies. To my amazement, twenty- finest public gardens, receive invita• five letters and faxes quickly arrived, tions to private gardens, shop the best along with maps and directions to nurseries for specimen purchases? nurseries. Several people offered to How do you plan efficiently for costly accompany us to nurseries or invited travel when language limitations and us to visit their gardens or the gardens social conventions (such as introduc• of friends. -

ART, ARCHITECTURE, and the ASAI SISTERS by Elizabeth Self

ART, ARCHITECTURE, AND THE ASAI SISTERS by Elizabeth Self Bachelor of Arts, University of Oregon, 2007 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of the Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Elizabeth Self It was defended on April 6, 2017 and approved by Hiroshi Nara, Professor, East Asian Languages and Literatures Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Assistant Professor, History of Art and Architecture Katheryn Linduff, Professor Emerita, History of Art and Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Karen Gerhart, Professor, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by Elizabeth Self 2017 iii ART, ARCHITECTURE, AND THE ASAI SISTERS Elizabeth Self, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 In early modern Japan, women, like men, used art and architectural patronage to perform and shape their identities and legitimate their authority. Through a series of case studies, I examine the works of art and architecture created by or for three sisters of the Asai 浅井 family: Yodo- dono 淀殿 (1569-1615), Jōkō-in 常高院 (1570-1633), and Sūgen-in 崇源院 (1573-1626). The Asai sisters held an elite status in their lifetimes, in part due to their relationship with the “Three Unifiers” of early 17th century Japan—Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582), Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537- 1589), and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616). As such, they were uniquely positioned to participate in the cultural battle for control of Japan. In each of my three case studies, I look at a specific site or object associated with one of the sisters.