Image, Precariousness and the Logic of Cultural Production in Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frog King: Totem: an Evolution

Valerie C. Doran Frog King: Totem: An Evolution n inimitable force unto himself, Frog King (a.k.a. Kwok Mang Ho) is a pioneering conceptual and performance artist who A has been breaking boundaries in Hong Kong and beyond since the late 1960s. Frog King’s artistic awareness is marked by a deeply integrated hybridity derived from dual roots based in two very different aesthetic-philosophical systems. One root draws from elements of Chinese cosmological philosophy that underlie all Chinese traditional art forms, in particular the connective mutability of the five elements of water, earth, fire, metal, and wood. In different manifestations these elements and their transmutations are present physically throughout Frog King’s work. The other root draws from the contemporary “art is life” philosophy of influential artists like Alan Kaprow and Fluxus artist Naim Jun Paik, early exponents of the happening and of the dissolution of the divide between artist and audience/art and daily life. In Frog King, the creative and philosophical DNA of these seemingly disparate and even incongruous sources of influence have mutated into a being of enormous creative vitality and a kind of all-embracing, life-affirming anarchy. Left: Korean video artist Nam Jun Paik wearing "froggie sunglasses" for One Second Live Body Performance, 1994, New York City. Right: Mother and son wearing "froggie sunglasses" for One Second Live Body Performance, À}Ì«>ÊUÊ Hongkornucopia, Venice Biennale, 2011. Courtesy of the artist. This quality of hybridity is represented in the amphibious nature of the frog and captured in Frog King’s seal or emblem of the abstracted frog face, whose two triangular eyes also imply a bridge or a pair of sails as symbols of connectivity. -

The Art of Tsang Tsou-Choi Pdf, Epub, Ebook

KING OF KOWLOON: THE ART OF TSANG TSOU-CHOI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tsang Tsou-Choi | 256 pages | 28 Feb 2014 | DAMIANI | 9788862082716 | English | Bologna, Italy King of Kowloon: The Art of Tsang Tsou-choi PDF Book A caption reads:. His writing style is influenced by the type of text found in a traditional Chinese almanac utilizing small and large fonts together, with important characters marked extra bold. A portion of proceeds from the exhibition and publication project will benefit the creation of a new foundation to oversee further research, exhibition, and collection of the work and legacy of the artist. Anderson, B. Lost your password? By offering certain possibilities for public intervention alongside a concerted disavowal of social responsibility, Tsang becomes, in retrospect, a key figure for cultural production today. Exhibition catalogue. Nora, P. At 16 he moved to Hong Kong to live with an uncle, later receiving citizenship. As well, the traditional medicinal oils that Tsang used to soothe his injured legs and the crushed Coca-Cola cans he left around his apartment after he guzzled his staple drink, all serve as reminders of the banality of his life outside of writing. His writing eventually became a part of the Hong Kong landscape. July 27, p. This is a preview of subscription content, log in to check access. Subscribe me to the Ocula newsletter. Benjamin, W. Zeng Chaofeng, one generation removed from Zeng Guangzhen, was son-in-law to the Zhou emperor, and had lived for a time in Kowloon. To fight it is like fighting the status quo. -

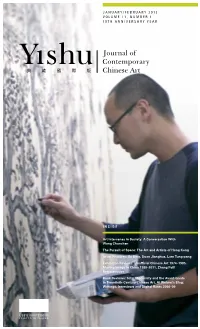

The Art and Artists of Hong Kong

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2012 VOLUME 11, N UMBER 1 10TH ANNIV ERSARY YEAR INSI DE Art Intervenes in Society: A Conversation With Wang Chunchen The Pursuit of Space: The Art and Artists of Hong Kong Artist Features: Xu Bing, Duan Jianghua, Lam Tung-pang Exhibition Reviews: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974–1985, Moving Image in China 1988–2011, Zhang Peili Retrospective Book Reviews: Total Modernity and the Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Chinese Art, Ai Weiwei’s Blog: Writings, Interviews and Digital Rants 2006–09 US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 16 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1, JANUA R Y/FEBRUA R Y 2012 CONTENTS Editor’s Note 30 Contributors 6 Wu Street: Tracing Lineages of the Internationalization of the Art World Orianna Cacchione 16 Revolution and Power: The Paintings of Duan Jianghua Robert C. Morgan 37 30 The Best of Times: Lam Tung-pang’s Long View Under Scrutiny Abby Chen 37 A Conversation With Lam Tung-pang Abby Chen 52 The Pursuit of Space: The Art and Artists of Hong Kong Celine Y. Lai 66 66 Art Intervenes in Society: A Conversation with Wang Chunchen Marie Leduc 82 Blooming in the Shadows: Unofficial Chinese Art, 1974–1985 Jonathan Goodman 96 Moving Image in China: 1988–2011 and Certain Pleasures: Zhang Peili Retrospective Xhingyu Chen 82 102 Fictions of Nationhood Robert Linsley 109 Chinese Name Index 96 Cover: Lam Tung-pang working on Past Continuous Tense, 2011, charcoal and image transfer on wood. Photo: Gordon Lo. Courtesy of the artist and Hong Kong Art Centre. We thank JNBY Art Projects, Canadian Foundation of Asian Art, Mr. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 1 April 2009 the Council Met at Eleven O'clock

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 April 2009 5891 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 1 April 2009 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. 5892 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 April 2009 THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT CHAN WAI-YIP THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

Chinese Participation in the 50Th Venice Biennale the Spectre Of

JUNE 2003 SUMMER ISSUE Chinese Participation in the 50th Venice Biennale The Spectre of Being Human The Contemporary Artistic Deconstruction—and Reconstruction—of Brush and Ink Painting Looking Ahead: Dialogues in Asian Contemporary Art US$10.00 NT$350.00 YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art Volume 2, Number 2, June 2003 Katy Hsiu-chih Chien Ken Lum Zheng Shengtian Julie Grundvig Paloma Campbell Larisa Broyde Joyce Lin Judy Andrews, Ohio State University John Clark, University of Sydney Lynne Cooke, Dia Art Foundation Okwui Enwezor, Curator, Art Institute of Chicago Britta Erickson, Independent Scholar & Curator Fan Di’an, Central Academy of Fine Arts Fei Dawei, Independent Curator Gao Minglu, New York State University Hou Hanru, Independent Curator & Critic Katie Hill, Independent Critic & Curator Martina Köppel-Yang, Independent Critic & Historian Sebastian Lopez, Gate Foundation and Leiden University Lu Jie, Independent Curator Charles Merewether, Getty Research Institute Ni Tsai Chin, Tunghai University Apinan Poshyananda, Chulalongkorn University Chia Chi Jason Wang, Art Critic & Curator Wu Hung, University of Chicago Art & Collection Group Ltd. Leap Creative Group Raymond Mah Gavin Chow Jeremy Lee Chong-yuan Image Ltd., Taipei - Yishu is published quarterly in Taipei, Taiwan, and edited in Vancouver, Canada. From 2003, the publishing date of Yishu will be March, June, September, and December. Editorial inquiries and manuscripts may be sent to the Editorial Office: Yishu 1008-808 Nelson Street, Vancouver, B.C. V6Z 2H2 Canada Phone: (1) 604-488-2563, Fax: (1) 604-591-6392 E-mail: [email protected] Subscription inquiries may be sent to: Journals Department University of Hawai’i Press 2840 Kolowalu Street, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA Phone: 1-808-956-8833; Fax: 1-808-988-6052 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] The University of Hawai’i Press accepts payment by Visa or Mastercard, cheque or money order (in U.S. -

Yishu 73 Web.Pdf

MARCH/A P R I L 2 0 1 6 VOLUM E 15, NUM BER 2 INSI DE Artist Features: Liu Ding, Maleonn, Frog King, Jin Shan, Maryn Varbanov Conversations: Lee Ufan, Siu King-Chung Exhibition: Really, Socialism?! US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TA IWAN 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 2, MARCH/APRIL 2016 C ONTENTS 21 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 Epiphany of Objects: Maleonn’s Papa’s Time Machine Julie Chun 21 Frog King: Totem: An Evolution 44 Valerie C. Doran 39 Frog King: Always a Step Ahead Christie Lee 44 A Conversation with Lee Ufan Stephanie Chou Wanjing 52 Really, Socialism?! Kang Kang 52 60 New Man: Liu Ding’s Approach and Situation Luan Zhichao 74 Episteme of Multiple Histories Julie Chun 97 A Conversation with Siu King-Chung about the Community Museum Project Sally Lai 108 Chinese Name Index 60 Cover: Maryn Varbanov and Song Huai-Kuei, black-and-white 74 photograph. Courtesy of Boriana Song. We thank JNBY Art Projects, D3E Art Limited, Chen Ping, and Stephanie Holmquist and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. 1 Vol. 15 No. 2 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art PRESIDENT Katy Hsiu-chih Chien LEGAL COUNSEL Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C. C. Liu Yishu 73 opens with a text on the innovative FOUNDING EDITOR Ken Lum handmade puppets developed by Shanghai artist EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Keith Wallace Maleonn. Puppetry is an area of creative practice MANAGING EDITOR Zheng Shengtian EDITORS Julie Grundvig that has received scant serious attention from Kate Steinmann the art world, and Maleonn's incorporation of Chunyee Li EDITORS (CHINESE VERSION) Yu Hsiao Hwei various found objects into the construction of Chen Ping his theatrical presentations demonstrates the Guo Yanlong CIRCULATION MANAGER Larisa Broyde kind of resourcefulness and imagination that is WEB SITE EDITOR Chunyee Li characteristic of the bricoleur. -

Colonial Local Relations Through Things, Places, and Bodies in Hong Kong Culture and Society

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2019 Reconfiguring <Post->Colonial Local Relations through Things, Places and Bodies in Hong Kong Culture and Society Wu, Helena Yuen-Wai Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-174131 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Wu, Helena Yuen-Wai. Reconfiguring <Post->Colonial Local Relations through Things, Places and Bodies in Hong Kong Culture and Society. 2019, University of Zurich, Faculty of Arts. Reconfiguring ‘Post-’colonial Local Relations through Things, Places, and Bodies in Hong Kong Culture and Society Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of the University of Zurich for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Helena Yuen-wai Wu Accepted in the fall semester 2017 on the recommendation of the Doctoral Committee: «Prof. Dr. Andrea Riemenschnitter» Prof. Dr. Sandro Zanetti Prof. Dr. Stephen Yiu-wai Chu Zürich, 2019 ABSTRACT The thesis explores how Hong Kong’s local is varyingly conceived and perceived, and how different local relations are constellated through the representation of thing, place, and bodies in cultural expression such as cinema, literature, and others, and their subsequent circulation in Hong Kong culture and society against different socio-political contexts. After the reversion of the sovereignty over Hong Kong from Britain to China in 1997, several critical moments started to emerge one after another: from the Asian financial breakdown in 2002, the SARS epidemic outbreak in 2003, to the civil disobedience campaign Umbrella Movement in 2014.