Aviation Short Investigation Bulletin, Third Quarter 2011, Issue 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meteorologia

MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 15/SDOP, DE 25 DE JULHO DE 2006. Aprova a reedição da Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, inciso IV, da Portaria DECEA n°136-T/DGCEA, de 28 de novembro de 2005, RESOLVE: Art. 1o Aprovar a reedição da ICA 105-1 “Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas”, que com esta baixa. Art. 2o Esta Instrução entra em vigor em 1º de setembro de 2006. Art. 3o Revoga-se a Portaria DECEA nº 131/SDOP, de 1º de julho de 2003, publicada no Boletim Interno do DECEA nº 124, de 08 de julho de 2003. (a) Brig Ar RICARDO DA SILVA SERVAN Chefe do Subdepartamento de Operações do DECEA (Publicada no BCA nº 146, de 07 de agosto de 2006) MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 33 /SDOP, DE 13 DE SETEMBRO DE 2007. Aprova a edição da emenda à Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, alínea g, da Portaria DECEA n°34-T/DGCEA, de 15 de março de 2007, RESOLVE: Art. -

Annual Report 19

Darwin Alice Springs Tennant Creek A Airport Development Group International Airport Airport Airport Annual Report 19 . Highlights 2018–19 We reached a milestone The National Critical Care In October 2018, Alice Springs of 21 years since the three and Trauma Response Centre received the first of four airports were privatised was completed at Darwin charter flights from Tokyo, under the NT Airports International Airport in Nagoya and Osaka, Japan, in banner, celebrating with April 2019, creating a world- more than 10 years. a special airside premiere class, on-airport Emergency screening of the aviation Medical Retrieval Precinct. history film ‘The Sweet Little Note of the Engine.’ Virgin Australia launched a new three-times-weekly We refurbished an seasonal service to Denpasar, underused part of the Bali, in April 2019. Sustainability reporting Darwin terminal into the introduced. Emissions target ‘Green Room’, a pop-up developed and on track to community arts space, have zero net emissions by launching it in August 2018. SilkAir announced an 2030 (scope 1 and 2). increase in weekly services between Darwin and Singapore from July 2019, Ian Kew, CEO, continued marking its seventh year of Runway overlay works as Chairman of the Darwin operations to Darwin with a commenced in Alice Springs Major Business Group and seventh weekly service. at a value of circa Chairman of the Darwin $20 million. Festival. ADG staff and the company contributed $18,000 to two ‘Happy or Not’ instant community causes from our $1.4 million infrastructure customer feedback Workplace Giving initiative. boost at Tennant Creek platforms installed in Alice for improved fencing and Springs and Darwin. -

COVID-19 UPDATE – 21St January 2021

COVID-19 UPDATE – 21st January 2021 MANDATORY FACE MASKS REQUIRED AT GOVE AIRPORT On Friday 8th January 2021, the Prime Minister announced (National Cabinet agreed) mandatory use of masks in domestic airports and on all domestic commercial flights. Furthermore, the NT Chief Health Officer Directions make it mandatory from the 20th January 2021 for face masks to be worn at all major NT airports and while on board an aircraft. Masks must be worn when inside the airport terminal building and when on the airfield. Children under the age of 12 and people with a specified medical condition are not required to wear a mask. Mask wearing is mandatory at the following Northern Territory airports: • Darwin International Airport • Alice Springs Airport • Connellan Airport - Ayers Rock (Yulara) • Gove Airport • Groote Eylandt A person is not required to wear a mask during an emergency or while doing any of the following: • Consuming food or beverage • Communicating with a person who is hearing impaired. • Wearing an oxygen mask AIRPORT & TRAVELLING • PLEASE NOTE: To reduce the challenges with social distancing and to minimise risks, only Airline passengers will be able to enter the Airport terminal, • please drop-off and pick-up passengers outside of the terminal building It is the responsibility of individuals to make sure they have a mask to wear when at major NT airports and while on board an aircraft. Additional Information: • Please be aware of the NT Government Border Controls, which may be in place https://coronavirus.nt.gov.au/travel/interstate-arrivals • https://www.interstatequarantine.org.au/state-and-territory-border-closures/ • AirNorth schedule - https://www.airnorth.com.au/flying-with-us/before-you-fly/arrivals- and-departures • https://www.cairnsairport.com.au/travelling/airport-guide/covid19/ . -

Premium Location Surcharge

Premium Location Surcharge The Premium Location Surcharge (PLS) is a levy applied on all rentals commencing at any Airport location throughout Australia. These charges are controlled by the Airport Authorities and are subject to change without notice. LOCATION PREMIUM LOCATION SURCHARGE Adelaide Airport 14% on all rental charges except fuel costs Alice Springs Airport 14.5% on time and kilometre charges Armidale Airport 9.5% on all rental charges except fuel costs Avalon Airport 12% on all rental charges except fuel costs Ayers Rock Airport & City 17.5% on time and kilometre charges Ballina Airport 11% on all rental charges except fuel costs Bathurst Airport 5% on all rental charges except fuel costs Brisbane Airport 14% on all rental charges except fuel costs Broome Airport 10% on time and kilometre charges Bundaberg Airport 10% on all rental charges except fuel costs Cairns Airport 14% on all rental charges except fuel costs Canberra Airport 18% on time and kilometre charges Coffs Harbour Airport 8% on all rental charges except fuel costs Coolangatta Airport 13.5% on all rental charges except fuel costs Darwin Airport 14.5% on time and kilometre charges Emerald Airport 10% on all rental charges except fuel costs Geraldton Airport 5% on all rental charges Gladstone Airport 10% on all rental charges except fuel costs Grafton Airport 10% on all rental charges except fuel costs Hervey Bay Airport 8.5% on all rental charges except fuel costs Hobart Airport 12% on all rental charges except fuel costs Kalgoorlie Airport 11.5% on all rental -

Document Title

COVID-19 Management Plan COVID-19 Management Plan Table of Contents 1 Distribution List ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Copies ............................................................................................................................................. 4 2 Amendment Record ................................................................................................................................. 4 3 Purpose .................................................................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Scope .............................................................................................................................................. 4 3.2 Documentation ................................................................................................................................ 4 4 Approvals ................................................................................................................................................. 5 5 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 5 5.1 Spread ............................................................................................................................................. 5 5.2 Symptoms ...................................................................................................................................... -

River Murray Operations Weekly Report 30Th January 2013

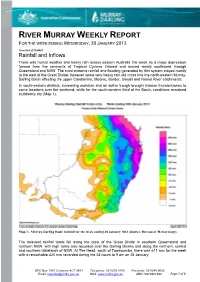

RIVER MURRAY WEEKLY REPORT FOR THE WEEK ENDING WEDNESDAY, 30 JANUARY 2013 Trim Ref: D13/4901 Rainfall and Inflows There was humid weather and heavy rain across eastern Australia this week as a major depression formed from the remnants of Tropical Cyclone Oswald and moved slowly southward through Queensland and NSW. The most extreme rainfall and flooding generated by this system stayed mostly to the east of the Great Divide; however some very heavy rain did cross into the north-eastern Murray- Darling Basin affecting the upper Condamine, Moonie, Border, Gwydir and Namoi River catchments. In south-eastern districts, increasing moisture and an active trough brought intense thunderstorms to some locations over the weekend, while for the south-western third of the Basin, conditions remained stubbornly dry (Map 1). Map 1 - Murray-Darling Basin rainfall for the week ending 30 January 2013 (Source: Bureau of Meteorology). The heaviest rainfall totals fell along the crest of the Great Divide in southern Queensland and northern NSW, with high totals also recorded over the Darling Downs and along the northern, central and southern tablelands of NSW. At The Head, south of Toowoomba, there was 611 mm for the week with a remarkable 425 mm recorded during the 24 hours to 9 am on 28 January. GPO Box 1801 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6279 0100 Facsimile: 02 6248 8053 Email: [email protected] Web: www.mdba.gov.au ABN 13679821382 Page 1 of 6 Other heavy totals in Queensland included 381 mm at Maryvale, 328 mm at Toowoomba, 214 mm at Goondiwindi, and 179 mm at Dalveen. -

Northern Territory June 2012 Monthly Weather Review Northern Territory June 2012

Monthly Weather Review Northern Territory June 2012 Monthly Weather Review Northern Territory June 2012 The Monthly Weather Review - Northern Territory is produced twelve times each year by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology's Northern Territory Climate Services Centre. It is intended to provide a concise but informative overview of the temperatures, rainfall and significant weather events in Northern Territory for the month. To keep the Monthly Weather Review as timely as possible, much of the information is based on electronic reports. Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of these reports, the results can be considered only preliminary until complete quality control procedures have been carried out. Major discrepancies will be noted in later issues. We are keen to ensure that the Monthly Weather Review is appropriate to the needs of its readers. If you have any comments or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact us: By mail Northern Territory Climate Services Centre Bureau of Meteorology PO Box 40050 Casuarina NT 0811 AUSTRALIA By telephone (08) 8920 3813 By email [email protected] You may also wish to visit the Bureau's home page, http://www.bom.gov.au. Units of measurement Except where noted, temperature is given in degrees Celsius (°C), rainfall in millimetres (mm), and wind speed in kilometres per hour (km/h). Observation times and periods Each station in Northern Territory makes its main observation for the day at 9 am local time. At this time, the precipitation over the past 24 hours is determined, and maximum and minimum thermometers are also read and reset. -

Company Profile

Commercial & Industrial Electrical & Mechanical Contracting, Fibre Optics, Communications, Data, Security, MATV, CCTV, Fire, Control Systems, Lightning Protection Systems High Voltage reticulation, Transformers Accredited PowerWater Contractor ABN 20 062 315 137 Company Profile Kellyco Electrical Services Pty Ltd was established in 1993 in Alice Springs. The company has enjoyed successful growth and expansion over the last 25 years, which has enabled us to establish an enviable reputation for professionalism and reliability. Our Darwin operation was opened in September 2008 and in 2012 we became an accredited member of Master Electricians. Kellyco initially specialised in remote area commercial and industrial projects. In 2001 we diversified and expanded completing more complex commercial projects in Alice Springs and Darwin. Over the last 25 years we have developed a sound infrastructure including over 20 registered vehicles and plant equipment, we hold Electrical Contracting Licences for Northern Territory and South Australia. Please find our NT Contractors Accreditation to give you an idea our Certificate Levels. Kellyco can offer a complete installation package for Commercial , High Rise, Large Residential Projects and Industrial Electrical Installations, Data (20 year Madison certified), Fibre Optic Cabling, Data and Communications, MATV, CCTV, Security, Fire, PA Systems, Lightning Protection, Control Systems, High Voltage Reticulation, Transformers, Low Voltage reticulation. We also manage our own Design and Construct packages all to AS/NZ standards. Federal Safety System Kellyco are accredited members of the Master Electricians Association which includes the Federally recognised Safety Connect Electrical Safety Management System. Our SafetyConnect program is a comprehensive, personalised safety management programme designed to dovetail into pre‐existing Federally Accredited Principle run programmes. -

Airport Categorisation List

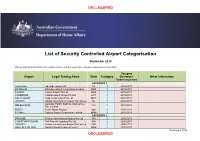

UNCLASSIFIED List of Security Controlled Airport Categorisation September 2018 *Please note that this table will continue to be updated upon new category approvals and gazettal Category Airport Legal Trading Name State Category Operations Other Information Commencement CATEGORY 1 ADELAIDE Adelaide Airport Ltd SA 1 22/12/2011 BRISBANE Brisbane Airport Corporation Limited QLD 1 22/12/2011 CAIRNS Cairns Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 CANBERRA Capital Airport Group Pty Ltd ACT 1 22/12/2011 GOLD COAST Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 DARWIN Darwin International Airport Pty Limited NT 1 22/12/2011 Australia Pacific Airports (Melbourne) MELBOURNE VIC 1 22/12/2011 Pty. Limited PERTH Perth Airport Pty Ltd WA 1 22/12/2011 SYDNEY Sydney Airport Corporation Limited NSW 1 22/12/2011 CATEGORY 2 BROOME Broome International Airport Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 CHRISTMAS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 HOBART Hobart International Airport Pty Limited TAS 2 29/02/2012 NORFOLK ISLAND Norfolk Island Regional Council NSW 2 22/12/2011 September 2018 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED PORT HEDLAND PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 SUNSHINE COAST Sunshine Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 29/06/2012 TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT Townsville Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 19/12/2014 CATEGORY 3 ALBURY Albury City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 ALICE SPRINGS Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited NT 3 11/01/2012 AVALON Avalon Airport Australia Pty Ltd VIC 3 22/12/2011 Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia NT 3 22/12/2011 AYERS ROCK Pty Ltd BALLINA Ballina Shire Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 BRISBANE WEST Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport Pty QLD 3 17/11/2014 WELLCAMP Ltd BUNDABERG Bundaberg Regional Council QLD 3 18/01/2012 CLONCURRY Cloncurry Shire Council QLD 3 29/02/2012 COCOS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 3 22/12/2011 COFFS HARBOUR Coffs Harbour City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 DEVONPORT Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty. -

AO-2016-062 Final – 14 October 2016

Separation issue due to runway incursion involving Cessna 172, VH-EKV, and Beech 58, VH-MLB Alice Springs Airport, Northern Territory, 16 June 2016 ATSB Transport Safety Report Aviation Occurrence Investigation AO-2016-062 Final – 14 October 2016 Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Publishing information Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office: 62 Northbourne Avenue Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 Telephone: 1800 020 616, from overseas +61 2 6257 4150 (24 hours) Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117, from overseas +61 2 6247 3117 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form license agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. -

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

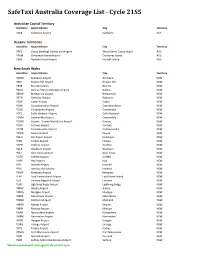

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

An Engineering Toolbox 15Th – 17Th October 2014 | Novotel Coffs Harbour Pacific Bay Resort

IPWEA NSW 2014 Conference An Engineering Toolbox 15th – 17th October 2014 | Novotel Coffs Harbour Pacific Bay Resort Platinum Partner: Gold Partner: WELCOME TO THE IPWEA NSW 2014 CONFERENCE Wednesday 15th to Friday 17th October 2014 ‘An Engineering Toolbox’ Our Industry continues to evolve. A special welcome to In a continuing changing and challenging environment elected representatives there is also a need for us to focus on BAU – business who are attending to TABLE OF CONTENTS as usual – and that’s why this year we are putting listen and learn from the our conference focus on giving you the knowledge, informative technical information and in some cases the skills to do your day papers. to day job. We want you to hear from your colleagues. It is critical that Welcome .........................................................................................3 What have been the outstanding successes of the year Council staff share this and what have been the really difficult obstacles that opportunity to learn more General Information ..........................................................................4 your fellow engineers have faced and overcome – or about all aspects of our Venue Floor Plan ..............................................................................5 not. industry. We want to We welcome you to the IPWEA NSW Division, 2014 increase their numbers Social Program ................................................................................6 Annual Conference. so please ensure you go back to your own council with