Grocery Monitor Report 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Company Address1 County Ahascragh Post Office Ahascragh

Company Address1 County Ahascragh Post Office Ahascragh Galway Barretts XL shop Keel, Achill Sound Mayo Bon Secours Hospital Pharmacy Galway City Brian Clarke's Daybreak Crusheen Clare Canavan's Shop Tuam Galway Centra (Cecils Foodstore) Collooney Sligo Claremorris Post Office Claremorris Mayo Clarke's Supervalu Barna Galway Clarkes Newsagents Ballina Mayo Cloonfad Post Office Cloonfad Galway Coffee Shop, GUH Galway City Cogaslann Agatha Carraroe Galway Connaugh's Express Shop Loughrea Galway Corrandulla Post Office Corrandulla Galway Costcutters Connemara Galway Coyles Supervalu Mountbellew Galway Craughwell P.O. Craughwell Galway Cuffe's Centra Belmullet Mayo Dailys Newsagents Claremorris Mayo Dohertys Costcutter & Post Office Mulranny Mayo Dunne's Supervalu Ballinasloe Galway Eurospar Loughrea Galway Feely's Pharmacy Tuam Galway Flanagans Shop Kilmaine Galway Flynn's Supervalu Turloughmore Galway Fr Griffin Road Post Office Galway City G&L Centra Galway City Galway Clinic Hospital Shop Galway City Glynns Centra Shop Carnmore Galway Grealy's Stores Oranmore Galway Grogans Concrete Cave Ballyhaunis Mayo Hamiltons Leenane Galway Headlines Corrib Shopping Centre Galway City Heneghan's Supervalu Glenamaddy Galway Holmes Centra Ballygar Galway Howley's Eurospar Dunmore Galway Hughes Supervalu Claregalway Galway Joyces Supermarket Athenry Galway Joyces Supermarket Knocknacarra Galway Joyces Supermarket Oranmore Galway Joyces Supermarket Headford Galway Joyces Supermarket Fr. Griffin Road Galway City Kavanagh's Supervalu Donegal Town Donegal -

Fuel Forecourt Retail Market

Fuel Forecourt Retail Market Grow non-fuel Are you set to be the mobility offerings — both products and Capitalise on the value-added mobility mega services trends (EVs, AVs and MaaS)1 retailer of tomorrow? Continue to focus on fossil Innovative Our report on Fuel Forecourt Retail Market focusses In light of this, w e have imagined how forecourts w ill fuel in short run, concepts and on the future of forecourt retailing. In the follow ing look like in the future. We believe that the in-city but start to pivot strategic Continuously pages w e delve into how the trends today are petrol stations w hich have a location advantage, w ill tow ards partnerships contemporary evolve shaping forecourt retailing now and tomorrow . We become suited for convenience retailing; urban fuel business start by looking at the current state of the Global forecourts w ould become prominent transport Relentless focus on models Forecourt Retail Market, both in terms of geographic exchanges; and highw ay sites w ill cater to long customer size and the top players dominating this space. distance travellers. How ever the level and speed of Explore Enhance experience Innovation new such transformation w ill vary by economy, as operational Next, w e explore the trends that are re-shaping the for income evolutionary trends in fuel retailing observed in industry; these are centred around the increase in efficiency tomorrow streams developed markets are yet to fully shape-up in importance of the Retail proposition, Adjacent developing ones. Services and Mobility. As you go along, you w ill find examples of how leading organisations are investing Further, as the pace of disruption accelerates, fuel their time and resources, in technology and and forecourt retailers need to reimagine innovative concepts to become more future-ready. -

Supervalu: How a Brave Local Brand Defied the Forces of Globalisation

SuperValu: How a brave local brand defied the forces of globalisation DDFH&B COMPANY PROFILE AGENCY The DDFH&B Group consists of DDFH&B Advertising, Goosebump, The Reputations Agency, RMG and Mindshare Media – making it one of the largest Irish companies in creative advertising, media buying and customer relationship/digital marketing. Together, they provide channel-neutral, integrated marketing communications campaigns that deliver real, measurable results. They achieve this level of integration by working in a number of small, multi-disciplined teams, calling it ‘fun sizing’. They continue to be one of the most successful agencies in Ireland, working with clients such as Kerry Foods, SuperValu, The National Lottery, eir, Littlewoods, Lucozade and Molson Coors. CLIENT AWARD LONG TERM EFFECTIVENESS Sponsored by GOLD 1 SuperValu: How a brave local brand defied the forces of globalisation DDFH&B INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND This is a story about long term effectiveness. It is a story about how a brave local retailer with daring ambition wrestled back leadership from Tesco and defied the forces of globalisation. SuperValu was founded in 1979 with a base of just 16 stores, mainly in Munster. While they had grown to 182 stores by 2004, and acquired Superquinn (another Irish retailer) in 2011, they were a retailer with two speeds, an urban speed and a rural speed. The urban speed was still reeling from the Superquinn takeover, when stores were rebranded to SuperValu in 2014. Superquinn had a more premium brand perception, much closer to the Waitrose proposition in the UK. Consumers were in a state of chassis as they felt they were paying convenience store prices in large supermarkets and were unfamiliar with the brand and mistrustful of its quality. -

List of Supermarkets & Stores: Sligo Town & Surrounds

List of Supermarkets & Stores: Sligo Town & Surrounds Contact Name Location Opening Times Deliveries Order Options / Notes Details Mon-Fri : 7am – 10pm Yes Centra Caltragh 071 9110077 Sat : 7.30am – 10pm Phone Sun : 8am – 10pm Mon-Fri: 7.30am – 9pm Centra Catron Village 071 91 45530 Yes Click and Collect Sat-Sun: 8am-9pm Phone Cosgrove’s Centra Maugheraboy 071 91 38731 Mon-Sun 7am-11pm Yes Email Dawn Fresh Tesco Carpark 071 91 61346 9am-6pm Yes Phone Cleveragh Phone Londis 071 9170190 Mon-Sun 9am-7pm Yes Road Email Bundoran Mon-Fri: 6.30am- 10.10pm Mullins, Spar & Texaco 071 91 43408 Yes Phone Road Sat-Sun: 8am-10pm Cranmore 11am-1pm priority Aldi Mon – Sun : 9am-8pm No Road shopping times Mon – Wed: 8.30am-8pm Cranmore Thur&Fri: 8.30am-9pm Not on 11am-1pm priority Dunnes 071 914 2226 Sat: groceries shopping times Road Sun: 10am-7pm Finisklin Rd Mon – Sat: 8am – 10pm 9am-11am priority Lidl No Cranmore Rd Sun: 9am –9pm shopping Mon-Fri : 8am – 10pm Tesco O’Connell St 1890 928 404 Sat: 7am-10pm Click and Collect Sun: 9am – 10pm List of Supermarkets & Stores : Sligo County Contact Name Location Opening Times Deliveries Order Options Details Mon-Sat: 7.30am- 10pm Centra Collooney 071 91 67988 Yes Phone Sunday: 8am-9pm Mon-Sat: 7am- 10pm Centra Enniscrone 096 36417 Yes Click & Collect Sunday: 8am-10pm Mon-Sat: 8am-9pm Centra Gurteen 071 918 2030 Yes Phone Sun: 9am-7pm Mon-Sat: 7am-11pm Centra Tubbercurry 071 9186092 No Phone Sun :8am-11pm Mon : 9am-10pm Eurospar Tubbercurry 071 91 85034 Yes Phone Tue-Sun: 8am-10pm website - Mon-Fri: 8.30am-4.15pm -

Review of the Economic Impact of the Retail Cap

REVIEW OF THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF THE RETAIL CAP Report prepared for the Departments of Enterprise, Jobs and Innovation and Environment, Community and Local Government APRIL 2011 Review of the Economic Impact of the Retail Cap Executive Summary i 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Objectives of the study 1 1.2 Structure of the report 2 2. Background 3 2.1 Policy and legislative framework for retail planning 3 2.2 Overview of the current retail caps 4 3. Overview of recent retail sector developments 6 3.1 Economy wide developments 6 3.2 Retail developments 8 3.3 Structure of the retail market 15 4. Factors driving costs and competition in retail 35 4.1 Impact of the retail caps on costs 35 4.2 Impact of the retail caps on competition 38 4.3 Other factors that impact competition/prices 41 4.4 Impact of the retail cap on suppliers 42 5. Conclusions and recommendations 44 APPENDIX: Terms of Reference 48 Review of the Economic Impact of the Retail Cap Executive Summary One of the conditions of the EU-IMF Programme for Financial Support for Ireland is that ‘the government will conduct a study on the economic impact of eliminating the cap on the size of retail premises with a view to enhancing competition and lowering prices for consumers and discuss implementation of its policy implications with the Commission services’. This process must be concluded by the end of Q3 2011. Forfás was requested to undertake the study and worked closely with a steering group comprising officials from the Departments of Enterprise and Environment. -

Environmental Report 2001

Environmental Report 2001 1 Group Managing Director's Statement 2 Musgrave Group – an Introduction 3 Musgrave Environmental Charter 4 Communications 8 Waste Management 16 Supplies & Products 20 Buildings 24 Reporting 28 Summarised Environmental Indicators Group Managing Director’s Statement Dear Reader, impacts as we have many issues to contend We made a major commitment in the year with and systems to implement within our 2000, with the publication of our Corporate complex business structure. I can say with Environmental Charter, a first for any Irish- confidence that our immediate challenge for based retail and distribution business, towards managing the environment in a proper manner a strong philosophy of leadership and is to measure accurately our environmental communications with our stakeholders. As an burdens and progressive changes on a year- integral part of that public statement, we are to-year basis, so we can report accurately for now in a position to report our findings and future years and enable meaningful dialogue gauge our performance in our first Group and analysis with our stakeholders. Please be Environmental Report. assured that this will happen, but it will take time. In reading through the report, I was generally pleased to note how far we have progressed in As we improve and work towards integrating integrating key environmental issues with our the environment into our daily decision-making business activities. This report has highlighted processes and at the same time provide a two important criteria for us - the establishment strong leadership role to our trading partners, of our environmental status, which includes the we are mindful of other related issues which collection of baseline data, plus the also play a fundamental role in the way we implementation of projects aimed at improving carry out our business. -

Britain's Tesco Scraps Irish Supplier Over Horse Meat Scare 30 January 2013

Britain's Tesco scraps Irish supplier over horse meat scare 30 January 2013 British retail giant Tesco said Wednesday it has "Ultimately Tesco is responsible for the food we axed an Irish beef supplier which sparked a food sell, so it is not enough just to stop using the scare after horse DNA was found in beefburgers in supplier." Britain and Ireland, where horse meat consumption is taboo. "We want to leave customers in no doubt that we will do whatever it takes to ensure the quality of Tesco said in a statement that it has decided to their food and that the food they buy is exactly what stop using Silvercrest after uncovering evidence the label says it is," added Smith. that it used meat from non-approved suppliers, mirroring a move by US fast-food chain Burger The consumption of horse meat is a common sight King last week. in central Asia, China, Latin America and parts of Europe. Two weeks ago, the Food Safety Authority of Ireland (FSAI) had revealed that up to 29 percent (c) 2013 AFP of the meat content of some beefburgers was in fact horse, while they also found pig DNA. The frozen burgers were on sale in high-street supermarket chains Tesco and Iceland in both Britain and Ireland, and in Irish branches of Lidl, Aldi and Dunnes Stores. The FSAI had said burgers had been made at two processing plants in Ireland and one in northern England. Following the news, Britain's biggest retailer Tesco issued an immediate apology and pledged to investigate the matter. -

Lidl Expanding to New York with Best Market Purchase

INSIDE TAKING THIS ISSUE STOCK by Jeff Metzger At Capital Markets Day, Ahold Delhaize Reveals Post-Merger Growth Platform Krasdale Celebrates “The merger and integration of Ahold and Delhaize Group have created a 110th At NYC’s Museum strong and efficient platform for growth, while maintaining strong business per- Of Natural History formance and building a culture of success. In an industry that’s undergoing 12 rapid change, fueled by shifting customer behavior and preferences, we will focus on growth by investing in our stores, omnichannel offering and techno- logical capabilities which will enrich the customer experience and increase efficiencies. Ultimately, this will drive growth by making everyday shopping easier, fresher and healthier for our customers.” Those were the words of Ahold Delhaize president and CEO Frans Muller to the investment and business community delivered at the company’s “Leading Wawa’s Mike Sherlock WWW.BEST-MET.COM Together” themed Capital Markets Day held at the Citi Executive Conference Among Those Inducted 20 In SJU ‘Hall Of Honor’ Vol. 74 No. 11 BROKERS ISSUE November 2018 See TAKING STOCK on page 6 Discounter To Convert 27 Stores Next Year Lidl Expanding To New York With Best Market Purchase Lidl, which has struggled since anteed employment opportunities high quality and huge savings for it entered the U.S. 17 months ago, with Lidl following the transition. more shoppers.” is expanding its footprint after an- Team members will be welcomed Fieber, a 10-year Lidl veteran, nouncing it has signed an agree- into positions with Lidl that offer became U.S. CEO in May, replac- ment to acquire 27 Best Market wages and benefits that are equal ing Brendan Proctor who led the AHOLD DELHAIZE HELD ITS CAPITAL MARKETS DAY AT THE CITIBANK Con- stores in New York (26 stores – to or better than what they cur- company’s U.S. -

Booker Symbol Retail

Booker Symbol Retail Insight on shoppers: insight on stores July 2018 © IGD 2018 The UK’s biggest symbol network Premier the biggest single fascia Now encompassing over 5,600 stores the Booker retail symbol network has twice the number of the next largest symbol group or convenience chain in the UK. Total combined estimated retail sales are now £4.5bn. Operating a portfolio of four fascias Booker Booker symbol retail: store numbers symbol has a breadth of offer to meet the needs of a wide range of differing retailer 2017 2018 change needs comprising: Premier* – flexible entry level package for Premier* 3,332 3,343 +11 small stores with supply from cash & carry depots Londis 1,826 1,957 +131 Londis – fully-serviced package for smaller stores supplied through Booker Retail Budgens 159 226 +67 Partners distribution network Budgens – Tailored support package for Family Shopper 63 75 +12 larger stores including an emphasis on fresh Family Shopper – A value-focused package Total 5,380 5,601 +221 offering neighbourhood discount format © IGD 2018 Source: IGD Research * Includes Premier Express fascia variant Page 2 What defines the Booker retail symbol shopper? Top shopper Top-up is the leading mission across all missions in three fascias Tobacco/lottery/news is the second most frequent mission in Premier and Londis Budgens has significantly the largest incidence of evening meal missions Premier has the highest incidence of food- for-now missions % of shoppers on last trip shopping for Premier Londis Budgens Top-up 45 50 59 Evening meal 15 13 35 Food-for-now 26 15 18 Tobacco/lottery/news 41 42 29 © IGD 2018 Source: IGD ShopperVista Page 3 As Booker looks to the future, and the new possibilities presented by its tie-up with Stores of the Tesco, we visited three of its most recently redeveloped symbol retail stores. -

The Kirby Collection Catalogue Irish College Rome

Archival list The Kirby Collection Catalogue Irish College Rome ARCHIVES PONTIFICAL IRISH COLLEGE, ROME Code Date Description and Extent KIR/1836-1861/ 9 15 September Holograph letter from J.P. Cooke, Waterford, to Kirby: 1837 condolences on father’s death. 4pp 10 20 September Holograph letter from M.V. Ryan, Abbot, Mt. Melleray, to 1837 Kirby: introducing two “members of a Religious body in the Queen’s County and other parts of Ireland” and asking to have them introduced to the General of Cists [Cistercians]. 3pp 11 22 September Holograph letter from William Carroll, Waterford, to Kirby: 1837 consulting Dr. Kirby on vocation. 4pp 12 22 September Holograph letter from [J.] Dowley, St. John’s College, 1837 Waterford, to Kirby: applying for faculties. 4pp 13 10 October Holograph letter from Ellen Byrne, 3 Avoca Place to Kirby: 1837 thanks for money. Home News. 4pp 14 27 November Holograph letter from William Kirby [brother], Limerick, to 1837 Kirby: Dr. Kirby recovered from serious illness. Nephew got habit in Mt. Melleray. General home news and politics. 4pp 15 1 February Two holograph letters. First letter from Denis Placid Byrne, 1838 [nephew], Mt. Melleray, to Kirby: details about entering Mt. Melleray Abbey which is scarcely half finished as yet. Second letter from Ellen Byrne [sister] with home news. 4pp 16 28 May Holograph letter from Rosanna O’Ferrall, Naples, to Kirby: 1838 seen, heard and noted around Naples 6pp 17 14 August Holograph letter from Louisa O’Ferrall, Naples, to Kirby: 1838 touring in Sicily. 4pp 2 Archives Irish College Rome Code Date Description and Extent KIR/1836-1861/ 18 10 September Holograph letter from William Carroll, Waterford, to Kirby: 1838 discussing his vocation to become a Trappist. -

Survey of Retailers

1 1. Contents 1. Contents ............................................................................................................. 2 2. Executive summary .............................................................................................. 3 Background and methodology ..................................................................................... 3 Key findings ............................................................................................................. 3 3. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 5 Research objectives ................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 5 Sample .................................................................................................................... 5 Participation criteria .................................................................................................. 8 Fieldwork ................................................................................................................. 8 Presentation of results ............................................................................................... 9 Respondent profile .................................................................................................. 10 4. Supply arrangements and local competition ......................................................... -

Merger Control Update 2018 Merger Control Update

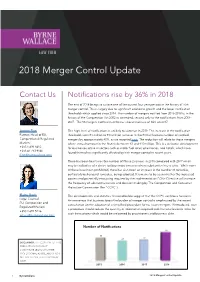

Merger Control Update 2018 Merger Control Update Contact Us Notifications rise by 36% in 2018 The end of 2018 brings to a close one of the busiest four year periods in the history of Irish merger control. This is largely due to significant economic growth and the lower notification thresholds which applied since 2014. The number of mergers notified from 2015-2018 is, in the history of the Competition Act 2002 as amended, second only to the notifications from 2004- 2007. The 98 mergers notified in 2018 was also an increase of 36% on 2017. Joanne Finn This high level of notifications is unlikely to continue in 2019. The increase in the notification Partner, Head of EU, thresholds from €3 million to €10 million turnover in the ROI will reduce number of notified Competition & Regulated mergers by approximately 40%, as we reported here. The reduction will relate to those mergers Markets where annual turnover in the State is between €3 and €10 million. This is a welcome development +353 1 691 5412 for businesses active in sectors such as motor fuel retail, pharmacies, and hotels, which have +353 87 753 9160 found themselves significantly affected by Irish merger control in recent years. [email protected] There has been four times the number of Phase 2 reviews in 2018 compared with 2017 which may be indicative of a desire to focus more on cases where substantive issues arise. While none of these have been prohibited, there has also been an increase in the number of remedies, particularly behavioural remedies, being adopted.