Please Download Issue 1-2 2017 Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pomerania in the Medieval and Renaissance Cartography – from the Cottoniana to Eilhard Lubinus

Pomerania in the Medieval and Renaissance Cartography… STUDIA MARITIMA, vol. XXXIII (2020) | ISSN 0137-3587 | DOI: 10.18276/sm.2020.33-04 Adam Krawiec Faculty of Historical Studies Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-3936-5037 Pomerania in the Medieval and Renaissance Cartography – from the Cottoniana to Eilhard Lubinus Keywords: Pomerania, Duchy of Pomerania, medieval cartography, early modern cartography, maritime cartography The following paper deals with the question of the cartographical image of Pomer- ania. What I mean here are maps in the modern sense of the word, i.e. Graphic rep- resentations that facilitate a spatial understanding of things, concepts, conditions, processes, or events in the human world1. It is an important reservation because the line between graphic and non-graphic representations of the Earth’s surface in the Middle Ages was sometimes blurred, therefore the term mappamundi could mean either a cartographic image or a textual geographical description, and in some cases it functioned as an equivalent of the modern term “Geography”2. Consequently, there’s a tendency in the modern historiography to analyze both forms of the geographical descriptions together. However, the late medieval and early modern developments in the perception and re-constructing of the space led to distinguishing cartography as an autonomous, full-fledged discipline of knowledge, and to the general acceptance of the map in the modern sense as a basic form of presentation of the world’s surface. Most maps which will be examined in the paper were produced in this later period, so it seems justified to analyze only the “real” maps, although in a broader context of the geographical imaginations. -

The Death Penalty in Belarus

Part 1. Histor ical Overview The Death Penalty in Belarus Vilnius 2016 1 The Death Penalty in Belarus The documentary book, “The Death Penalty in Belarus”, was prepared in the framework of the campaign, “Human Rights Defenders against the Death Penalty in Belarus”. The book contains information on the death penalty in Belarus from 1998 to 2016, as it was in 1998 when the mother of Ivan Famin, a man who was executed for someone else’s crimes, appealed to the Human Rights Center “Viasna”. Among the exclusive materials presented in this publication there is the historical review, “A History of The Death Penalty in Belarus”, prepared by Dzianis Martsinovich, and a large interview with a former head of remand prison No. 1 in Minsk, Aleh Alkayeu, under whose leadership about 150 executions were performed. This book is designed not only for human rights activists, but also for students and teachers of jurisprudence, and wide public. 2 Part 1. Histor ical Overview Life and Death The Death penalty. These words evoke different feelings and ideas in different people, including fair punishment, cruelty and callousness of the state, the cold steel of the headsman’s axe, civilized barbarism, pistol shots, horror and despair, revolutionary expediency, the guillotine with a basket where the severed heads roll, and many other things. Man has invented thousands of ways to kill his fellows, and his bizarre fantasy with the methods of execution is boundless. People even seem to show more humanness and rationalism in killing animals. After all, animals often kill one another. A well-known Belarusian artist Lionik Tarasevich grows hundreds of thoroughbred hens and roosters on his farm in the village of Validy in the Białystok district. -

Pomorskie Voivodeship Development Strategy 2020

Annex no. 1 to Resolution no. 458/XXII/12 Of the Sejmik of Pomorskie Voivodeship of 24th September 2012 on adoption of Pomorskie Voivodeship Development Strategy 2020 Pomorskie Voivodeship Development Strategy 2020 GDAŃSK 2012 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. OUTPUT SITUATION ………………………………………………………… 6 II. SCENARIOS AND VISION OF DEVELOPMENT ………………………… 18 THE PRINCIPLES OF STRATEGY AND ROLE OF THE SELF- III. 24 GOVERNMENT OF THE VOIVODESHIP ………..………………………… IV. CHALLENGES AND OBJECTIVES …………………………………………… 28 V. IMPLEMENTATION SYSTEM ………………………………………………… 65 3 4 The shape of the Pomorskie Voivodeship Development Strategy 2020 is determined by 8 assumptions: 1. The strategy is a tool for creating development targeting available financial and regulatory instruments. 2. The strategy covers only those issues on which the Self-Government of Pomorskie Voivodeship and its partners in the region have a real impact. 3. The strategy does not include purely local issues unless there is a close relationship between the local needs and potentials of the region and regional interest, or when the local deficits significantly restrict the development opportunities. 4. The strategy does not focus on issues of a routine character, belonging to the realm of the current operation and performing the duties and responsibilities of legal entities operating in the region. 5. The strategy is selective and focused on defining the objectives and courses of action reflecting the strategic choices made. 6. The strategy sets targets amenable to verification and establishment of commitments to specific actions and effects. 7. The strategy outlines the criteria for identifying projects forming part of its implementation. 8. The strategy takes into account the specific conditions for development of different parts of the voivodeship, indicating that not all development challenges are the same everywhere in their nature and seriousness. -

Wake Forest Offense

JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2005 12 FOR BASKETBALL EVERYWHERE ENTHUSIASTS FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE ASSIST FABRIZIO FRATES SKIP PROSSER - DINO GAUDIO THE OFFENSIVE FUNDAMENTALS: the SPACING AND RHYTHM OF PLAY JONAS KAZLAUSKAS SCOUTING THE 2004 OLYMPIC GAMES WAKE FOREST paT ROSENOW THREE-PERSON OFFICIATING LARS NORDMALM OFFENSE CHALLENGES AT THE FIBA EUROBASKET 2003 TONY WARD REDUCING THE RISK OF RE-INJURY EDITORIAL Women’s basketball in africa is moving up The Athens Olympics were remarkable in many Women's sport in Africa needs further sup- ways. One moment in Olympic history deserves port on every level. It is not only the often special attention, especially as it almost got mentioned lack of financial resources and unnoticed during the many sensational perfor- facilities which makes it difficult to run proper mances during the Games - the women's classi- development programs. The traditional role of fication game for the 12th place. When the women in society and certain religious norms women's team from Nigeria celebrated a 68-64 can create further burdens. Saying that, it is win over Korea after coming back from a 18 - 30 obvious that the popularity of the game is margin midway through the second period, this high and Africa's basketball is full of talent. It marked the first ever African victory of a is our duty to encourage young female women's team in Olympic history. This is even players to play basketball and give them the the more remarkable, as it was only the 3rd opportunity to compete on the highest level. appearance of an African team in the Olympics against a world class team that was playing for The FIBA U19 Women’s World Championship Bronze just 4 years ago in Sydney. -

Development Prospects of Tourist Passenger Shipping in the Polish Part of the Vistula Lagoon

sustainability Article Development Prospects of Tourist Passenger Shipping in the Polish Part of the Vistula Lagoon Krystian Puzdrakiewicz * and Marcin Połom * Division of Regional Development, Faculty of Oceanography and Geography, University of Gda´nsk, 80-309 Gda´nsk,Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] (K.P.); [email protected] (M.P.) Abstract: The Vistula Lagoon is a cross-border area with high natural values and a developing market of tourist services. Passenger shipping is an important part of local tourism, but ship owners are insufficiently involved in planning processes and their views on creating shipping development are underrepresented. The article aims to compare the vision of the development of passenger shipping in the Polish part of the Vistula Lagoon between local governments creating the spatial policy and ship owners offering transport services. We have made an attempt to verify the development prospects. The collation of these visions was based primarily on the qualitative analysis of the content of planning and strategic documents (desk research method) and a survey conducted among all six ship owners. Thanks to the comparative analysis, it was possible to show similarities and differences and to indicate recommendations. The paper presents review of the available literature on the subject, thanks to which the research area was identified as unique in Europe. On the one hand, it is a valuable natural area, which is an important tourist destination, on the other hand, there are organizational and infrastructural limitations in meeting the needs of tourists. Then, field research was conducted, unpublished materials were collected, and surveys were conducted with the Citation: Puzdrakiewicz, K.; Połom, M. -

Samorząd Terytorialny W Pigułce System Samorządu W Polsce • GŁÓWNA MISJA: Planowanie I Wspieranie Rozwoju Regionu M.In

Samorząd terytorialny w pigułce System samorządu w Polsce • GŁÓWNA MISJA: planowanie i wspieranie rozwoju regionu m.in. poprzez wykorzystanie funduszy Województwo europejskich • ORGANY: sejmik województwa (wybieralny, zarząd województwa z marszałkiem na czele • GŁÓWNA MISJA: zapewnienie usług publicznych, których skala przekracza możliwości gminy, np. ochrona zdrowia, szkoły ponadgimnazjalne, Powiat bezpieczeństwo publiczne • ORGANY: rada powiatu (wybieralna), zarząd powiatu ze starostą na czele • GŁÓWNA MISJA: zapewnienie podstawowych usług publicznych – samorząd „pierwszego kontaktu” Gmina • ORGANY: rada gminy i wójt, burmistrz, prezydent miasta (organy wybieralne) Na czym polega Gmina jako podstawowa jednostka samorządu terytorialnego odpowiada za wszystkie misja gminy? sprawy o zasięgu lokalnym, które – zgodnie z założeniami ustawy o samorządzie > gminnym – mogą się przysłużyć „zaspokojeniu zbiorowych potrzeb wspólnoty”. Nawet jeśli prawo wyraźnie nie nakazuje gminom podejmowania określonych działań czy rozwiązywania konkretnych problemów, władze gminy nie mogą tego traktować jako wymówki dla swojej bierności. Gmina powinna aktywnie rozwiązywać problemy mieszkańców! Zgodnie z art. 1 ust. 1 ustawy o samorządzie gminnym oraz art. 16 ust. 1 Konstytucji RP mieszkańcy gminy tworzą z mocy prawa wspólnotę samorządową. Celem działań podejmowanych przez gminę powinno być zaspokajanie konkretnych potrzeb danej wspólnoty samorządowej. Na czym polega Powiat został utworzony, aby zarządzać usługami publicznymi, z którymi nie misja powiatu? poradziłyby sobie gminy, szczególnie mniejsze. Dlatego też powiat ponosi > odpowiedzialność za zarządzanie szpitalami, prowadzenie szkół ponadgimnazjalnych, urzędów pracy czy sprawy geodezji. Warto przy tym pamiętać, że wszystkie szczeble samorządu są od siebie niezależne, i tak np. powiat nie jest nadrzędny w stosunku do gmin. Na czym polega Najważniejszym zadaniem województwa jest wspieranie rozwoju całego regionu. misja województwa? W tym celu sejmik przyjmuje strategie opisujące plany rozwoju województwa. -

The Mediation of the Concept of Civil Society in the Belarusian Press (1991-2010)

THE MEDIATION OF THE CONCEPT OF CIVIL SOCIETY IN THE BELARUSIAN PRESS (1991-2010) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 IRYNA CLARK School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures ............................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 7 Declaration ....................................................................................................................... 8 Copyright Statement ........................................................................................................ 8 A Note on Transliteration and Translation .................................................................... 9 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ 10 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 11 Research objectives and questions ................................................................................... 12 Outline of the Belarusian media landscape and primary sources ...................................... 17 The evolution of the concept of civil society -

Stadtblatt Ribnitz-Damgarten Amtliches Mitteilungsblatt, Nr

Amtliches S t a d t b l a t t Ribnitz-Damgarten Amtliche Mitteilungen und Informationen der Stadt Ribnitz-Damgarten 22. Jahrgang Freitag, 19. Februar 2016 Nummer 2 Aus dem Inhalt: Sprechtage des Kontaktbeamten der Polizei Bekanntmachung von Ort, Zeit und Tages- ordnung der 13. Sitzung der Stadtver- 25. Februar 2016, 15:00 - 17:00 Uhr tretung Ribnitz-Damgarten Bürgerbüro Ahrenshagen, Todenhäger Str. 2 Beschlüsse der Stadtvertretung 3. März 2016, 15:00 - 17:00 Uhr Bekanntmachung des Wasser- und Boden- Rathaus Ribnitz, kleiner Saal verbandes „Recknitz-Boddenkette“ Sitzungsplan der Stadtvertretung und ihrer 10. März 2016, 15:00 - 17:00 Uhr Rathaus Damgarten, Rathaussaal Ausschüsse - März und April 2016 nächster Sonnabend-Sprechtag des Einwohnermeldeamtes Information des DRK-Blutspendedienstes 5. März 2016 von 09:00 - 11:00 Uhr Blutspendetermine in Ribnitz-Damgarten im Rathaus Ribnitz, Zimmer 113 Di., 8. März 2016, 14:00 - 18:00 Uhr Sprechtag der Schiedsstelle DRK-Kreisverband, Körkwitzer Weg 43 Ribnitz-Damgarten Fr., 1. April 2016, 14:30 - 18:00 Uhr Regionale Schule „R.-Harbig“, Schulstraße 13 17. März 2016 von 17:00 - 18:00 Uhr im Rathaus Ribnitz, Bürgerbüro, Zimmer 100 Di., 12. April 2016, 14:00 - 18:00 Uhr DRK-Kreisverband, Körkwitzer Weg 43 Fr., 29. April 2016, 09:00 - 12:00 Uhr nächster Sprechtag der Wossidlo-Gymnasium, Schulstraße 15 Rentenversicherung Nord Di., 3. Mai 2016, 13:00 - 16:00 Uhr Boddenklinik, Sandhufe 2 3. März 2016 von 09:00 - 12:00 Uhr und 13:00 - 18:00 Uhr im Rathaus Ribnitz, Rathaussaal Alle Gesunden im Alter von 18 - 68 Jahren (Erstspender bis 60 Jahre) werden gebeten, sich an den Blutspendeaktionen zu beteiligen. -

Materiały Zachodniopomorskie

MATERIAŁY ZACHODNIOPOMORSKIE Rocznik Naukowy Muzeum Narodowego w Szczecinie Nowa Seria Tom XII 2016 Szczecin 2016 Redaktor Anna B. Kowalska Sekretarz redakcji Bartłomiej Rogalski Członkowie redakcji Krzysztof Kowalski,Redaktor Dorota Naczelny Kozłowska, Rafał Makała Anna B. Kowalska Rada Naukowa dr hab. prof. UJ WojciechSekretarz Blajer, prof. Redakcji dr hab. Aleksander Bursche, prof. dr hab. WojciechBartłomiej Dzieduszycki, Rogalski prof. dr Hauke Jöns, dr hab. prof. UW Joanna Kalaga, dr hab. prof. UG Henryk Machajewski, dr Dmitrij Osipov,Członkowie dr hab. prof. Redakcji UWr Tomasz Płonka Krzysztof Kowalski, Dorota Kozłowska, Rafał Makała Recenzenci dr Justyna Baron, dr EugeniuszRada Cnotliwy, Naukowa dr hab. Andrzej Janowski, dr hab.dr prof.hab. UJprof. Wojciech PAN Michał Blajer, prof. Kara, Aleksander dr hab. prof. Bursche, UAM prof. Andrzej Wojciech Michałowski Dzieduszycki, dr hab. prof. UAM Jarosław Jarzewicz, prof. Hauke Jöns, dr hab. prof. UW Joanna Kalaga, dr hab. prof. UG HenrykTłumaczenie Machajewski, dr Dmitrij Osipov, dr hab. prof. UWr Tomasz Płonka Tomasz Borkowski, Michał Adamczyk Redakcja wydawnicza ProofreadingPiotr Wojdak Agnes Kerrigan Tłumaczenie Tomasz Borkowski,Redakcja Agnes wydawnicza Kerrigan (proofreading) Barbara Maria Kownacka, Marcelina Lechicka-Dziel Recenzenci dr hab. prof. UWr Artur Błażejewski, drProjekt hab. Mirosław okładki Hoffmann, dr hab. Andrzej Janowski, dr hab. prof. PAN MichałWaldemar Kara, dr hab. Wojciechowski Henryk Kobryń, dr Sebastian Messal, dr hab. prof. PAN Andrzej Mierzwiński, Aleksander Ostasz, prof. Marian Rębkowski, dr hab. prof. UŁ Seweryn Rzepecki,Skład Maciej i druk Słomiński, prof. Andrzej Wyrwa, dr XPRESShab. Gerd-Helge Sp. z o.o. Vogel AdresAdres redakcjiRedakcji Muzeum Narodowe w Szczecinie Muzeum Narodowe w Szczecinie 70-561 Szczecin, ul. Staromłyńska 27 70-561 Szczecin, ul. -

Gennady Kretinin

Gennady Kretinin Gennady Kretinin This article considers the problematic issue of the prehistory of the Kaliningrad ON THE PERIODISATION region. The author analyses different ap- proaches to the periodisation of the East OF THE BATTLE Prussian offensive, delimits the periods of its stages and determines the date of the FOR EAST PRUSSIA termination of the operation. IN 1944—1945 Key words: history, Kaliningrad region, war, operation, phases of war, of- fensive, East Prussia, Pillau, spit, Frische Nehrung, strait. The history of the Kaliningrad region goes back to April 7, 1946. On that day, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued the decree “On the establishment of the Königsberg region within the RSFSR”. On July 4, 1946, Königsberg was renamed Kaliningrad and the Konigsberg region be- came the Kaliningrad region [1, p. 469]. The western-most region of the Russian Federation has a rich military pre-history. Despite the long time that has passed since the end of the Sec- ond World War, the history of the war is in the focus of attention in Kalinin- grad. The discussion centres on political, sociocultural, demographic, and, of course, military issues. One of such issues is the controversy over the beginning and end of the military operation in East Prussia and the phases of the 1945 East Prussian Offensive per se. Military science has the term “periodisation of war”, which means the division of a war into markedly different phases. Each phase has certain content; different phases are distinguished by the form of military actions; the time framework marks the turning points in the course of a war according to the objective and character of the latter [2, vol. -

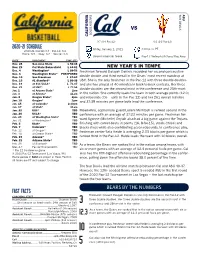

2020-21 Schedule Fast Facts Bears by the Numbers

SUN DEVILS ASU VS GOLDEN BEARS CALIFORNIA 0-7 (0-4 Pac-12) 6-2 (2-2 Pac-12) 2020-21 SCHEDULE Friday, January 1, 2021 2:00 p.m. PT 2020-21 Overall: 0-7• Pac-12: 0-4 Home: 0-5 • Away: 0-2 • Neutral: 0-0 Desert Financial Arena Pac-12 Network/Arizona/Bay Area DATE OPPONENT TIME (PT) Nov. 25 San Jose State L 56-48 Nov. 29 Cal State Bakersfield L 60-52 NEW YEAR’S IN TEMPE Dec. 4 Washington* L 80-53 Freshman forward Dalayah Daniels recorded her second-consecutive Dec. 6 Washington State* POSTPONED Dec. 10 San Francisco L 67-62 double-double and third overall in the Bears’ most recent matchup at Dec. 13 #1 Stanford* L 83-38 USC. She is the only freshman in the Pac-12 with three double-doubles Dec. 19 at #11 UCLA* L 71-37 and she has played all 40 minutes in back-to-back contests. Her three Dec. 21 at USC* L 77-54 Jan. 1 at Arizona State* 2pm double-doubles are the second most in the conference and 25th-most Jan. 3 at Arizona* 11am in the nation. She currently leads the team in both average points (12.0) Jan. 8 Oregon State* 2pm and rebounds (7.6 – sixth in the Pac-12) and her 261 overall minutes Jan. 10 Oregon* 1pm and 37:39 minutes per game both lead the conference. Jan. 15 at Colorado* 2:30pm Jan. 17 at Utah* 11am Jan. 22 USC* TBD Meanwhile, sophomore guard Leilani McIntosh is ranked second in the Jan. -

Nationalism in the Soviet and Post-Soviet Space: the Cases of Belarus and Ukraine Goujon, Alexandra

www.ssoar.info Nationalism in the Soviet and post-Soviet space: the cases of Belarus and Ukraine Goujon, Alexandra Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Arbeitspapier / working paper Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Goujon, A. (1999). Nationalism in the Soviet and post-Soviet space: the cases of Belarus and Ukraine. (Arbeitspapiere des Osteuropa-Instituts der Freien Universität Berlin, Arbeitsschwerpunkt Politik, 22). Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, Osteuropa-Institut Abt. Politik. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-440316 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use.