Tephrocactus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haseltonia Articles and Authors.Xlsx

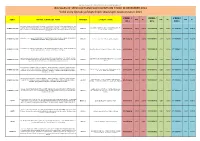

ABCDEFG 1 CSSA "HASELTONIA" ARTICLE TITLES #1 1993–#26 2019 AUTHOR(S) R ISSUE(S) PAGES KEY WORD 1 KEY WORD 2 2 A Cactus Database for the State of Baja California, Mexico Resendiz Ruiz, María Elena 2000 7 97-99 BajaCalifornia Database A First Record of Yucca aloifolia L. (Agavaceae/Asparagaceae) Naturalized Smith, Gideon F, Figueiredo, 3 in South Africa with Notes on its uses and Reproductive Biology Estrela & Crouch, Neil R 2012 17 87-93 Yucca Fotinos, Tonya D, Clase, Teodoro, Veloz, Alberto, Jimenez, Francisco, Griffith, M A Minimally Invasive, Automated Procedure for DNA Extraction from Patrick & Wettberg, Eric JB 4 Epidermal Peels of Succulent Cacti (Cactaceae) von 2016 22 46-47 Cacti DNA 5 A Morphological Phylogeny of the Genus Conophytum N.E.Br. (Aizoaceae) Opel, Matthew R 2005 11 53-77 Conophytum 6 A New Account of Echidnopsis Hook. F. (Asclepiadaceae: Stapeliae) Plowes, Darrel CH 1993 1 65-85 Echidnopsis 7 A New Cholla (Cactaceae) from Baja California, Mexico Rebman, Jon P 1998 6 17-21 Cylindropuntia 8 A New Combination in the genus Agave Etter, Julia & Kristen, Martin 2006 12 70 Agave A New Series of the Genus Opuntia Mill. (Opuntieae, Opuntioideae, Oakley, Luis & Kiesling, 9 Cactaceae) from Austral South America Roberto 2016 22 22-30 Opuntia McCoy, Tom & Newton, 10 A New Shrubby Species of Aloe in the Imatong Mountains, Southern Sudan Leonard E 2014 19 64-65 Aloe 11 A New Species of Aloe on the Ethiopia-Sudan Border Newton, Leonard E 2002 9 14-16 Aloe A new species of Ceropegia sect. -

Excerpted From

Excerpted from © by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. May not be copied or reused without express written permission of the publisher. click here to BUY THIS BOOK CHAPTER ›3 ‹ ROOT STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION Joseph G. Dubrovsky and Gretchen B. North Introduction Structure Primary Structure Secondary Structure Root Types Development and Growth Indeterminate Root Growth Determinate Root Growth Lateral Root Development Root System Development Adaptations to Deserts and Other Arid Environments Root Distribution in the Soil Environmental Effects on Root Development Developmental Adaptations Water and Mineral Uptake Root Hydraulic Conductivity Mineral Uptake Mycorrhizal and Bacterial Associations Carbon Relations Conclusions and Future Prospects Literature Cited rocky or sandy habitats. The goals of this chapter are to re- Introduction view the literature on the root biology of cacti and to pres- From the first moments of a plant’s life cycle, including ent some recent findings. First, root structure, growth, and germination, roots are essential for water uptake, mineral development are considered, then structural and develop- acquisition, and plant anchorage. These functions are es- mental adaptations to desiccating environments, such as pecially significant for cacti, because both desert species deserts and tropical tree canopies, are analyzed, and finally and epiphytes in the cactus family are faced with limited the functions of roots as organs of water and mineral up- and variable soil resources, strong winds, and frequently take are explored. 41 (Freeman 1969). Occasionally, mucilage cells are found in Structure the primary root (Hamilton 1970).Figure3.1nearhere: Cactus roots are less overtly specialized in structure than Differentiation of primary tissues starts soon after cell are cactus shoots. -

R. Kiesling Et Al

Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. 56 (1) 2021 R. Kiesling et al. - Typification of Opuntia australis (Cactaceae) TYPIFICATION OF OPUNTIA AUSTRALIS (CACTACEAE) WITH AN ORIGINAL PLATE FROM 1882 AND HISTORY OF THE PLANT’S FINDING TIPIFICACIÓN DE OPUNTIA AUSTRALIS (CACTACEAE) CON UNA LÁMINA ORIGINAL DE 1882 E HISTORIA DEL HALLAZGO DE LA PLANTA Roberto Kiesling1*, Jean-René Catrix2, Florence Tessier3 and Daniel Schweich4 SUMMARY 1. Member of the Carrera del The neotypification of Opuntia australis F.A.C.Weber, basionym of Pterocactus Investigador Científico, IADIZA – australis (F.A.C.Weber) Backeb., is made here thanks to the discovery of Weber’s CONICET, Mendoza. personal notes about it, and of two notebooks containing respectively a drawing 2. Cactophile, Éragny sur Oise, and a short description of that plant, both made at the time of its first collection in France. 1882. Outlined as well is the poorly documented scientific expedition that made this 3. Librarian at the botany library, first discovery and the cultivation of an early plant by F.E. Schlumberger on Weber’s Direction des Bibliothèques et de la behalf. A Weber’s note confirms he knew the mentioned illustration. A herbarium Documentation, Muséum National specimen from the same gathering has been found, but it cannot be considered d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France. original material since there is no evidence that it was seen by Weber. However, this 4. Retired from CNRS, Jonage, specimen is here designated as epitype. France KEY WORDS *[email protected] Cactaceae, Opuntioideae, Pterocactus australis, scientific expeditions, Typification. Citar este artículo RESUMEN KIESLING, R., J. -

South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) Lendel, Anita Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-93287 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Lendel, Anita. South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae). 2013, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) _________________________________________________________________________________ Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr.sc.nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Anita Lendel aus Kroatien Promotionskomitee: Prof. Dr. H. Peter Linder (Vorsitz) PD. Dr. Reto Nyffeler Prof. Dr. Elena Conti Zürich, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 3 Chapter 1. Phylogenetics and taxonomy of the tribe Cereeae s.l., with particular focus 15 on the subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae – Cactoideae) Chapter 2. Floral evolution in the South American tribe Cereeae s.l. (Cactaceae: 53 Cactoideae): Pollination syndromes in a comparative phylogenetic context Chapter 3. Contemporaneous and recent radiations of the world’s major succulent 86 plant lineages Chapter 4. Tackling the molecular dating paradox: underestimated pitfalls and best 121 strategies when fossils are scarce Outlook and Future Research 207 Curriculum Vitae 209 Summary 211 Zusammenfassung 213 Acknowledgments I really believe that no one can go through the process of doing a PhD and come out without being changed at a very profound level. -

Molecular Phylogeny and Character Evolution in Terete-Stemmed Andean Opuntias (Cactaceaeàopuntioideae) ⇑ C.M

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 65 (2012) 668–681 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Molecular phylogeny and character evolution in terete-stemmed Andean opuntias (CactaceaeÀOpuntioideae) ⇑ C.M. Ritz a, ,1, J. Reiker b,1, G. Charles c, P. Hoxey c, D. Hunt c, M. Lowry c, W. Stuppy d, N. Taylor e a Senckenberg Museum of Natural History Görlitz, Am Museum 1, D-02826 Görlitz, Germany b Justus-Liebig-University Gießen, Institute of Botany, Department of Systematic Botany, Heinrich-Buff-Ring 38, D-35392 Gießen, Germany c International Organization for Succulent Plant Study, c/o David Hunt, Hon. Secretary, 83 Church Street, Milborne Port DT9 5DJ, United Kingdom d Millennium Seed Bank, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew & Wakehurst Place, Ardingly, West Sussex RH17 6TN, United Kingdom e Singapore Botanic Gardens, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569, Singapore article info abstract Article history: The cacti of tribe Tephrocacteae (Cactaceae–Opuntioideae) are adapted to diverse climatic conditions Received 22 November 2011 over a wide area of the southern Andes and adjacent lowlands. -

Big Sales of Seed Cacti and Succulents on Stock In

BIG SALES OF SEED CACTI AND SUCCULENTS ON STOCK IN DECEMBER 2014 BIG SALES OF SEED CACTI AND SUCCULENTS ON STOCK IN DECEMBER 2014 Velké slevy výprodej přebytečných skladových zásob prosinec 2014 CODE / CODE / CODE / GENUS SPECIES , SUBSPECIES , FORM APPENDIX LOCALITY , STATE EUR Kč EUR Kč EUR Kč 20 s 60 s 500 s chionanthum ( Speg. ) Backeb. Kaktus-ABC [Backeb. & Knuth] 225. 1936 [12 Feb 1936] NICE WHITE YELLOW FLOWERING FORM / greyish-green body , stout straight spines in grey-brown , mix pure white and also yellow La Cabana / Angastaco to Molinos Road left side plains / alt. ACANTHOCALYCIUM BKN 56 B 0,08 € 2,00 Kč 0,20 € 5,00 Kč 1,60 € 40,00 Kč flowers , throat green, growing in large plains mostly with best spined form Gymnocalycium spegazzinii ssp. sarkae 1922 m , p. Salta , Argentina VY-010014-A VY-010014-B VY-010014-C ( mayor ) / chionanthum v. brevispinum YELLOW PINK TILL BROWNISH PECTINATE SPINES , GREEN SILVER BODY/ ACANTHOCALYCIUM BKN 51A La Vinita / near table / 1685 m , p. Salta , Argentina 0,08 € 2,00 Kč 0,20 € 5,00 Kč 1,60 € 40,00 Kč pectinate pink brown spines , large light yellow flower , violet stigma / VY-010008-A VY-010008-B VY-010008-C chionanthum v. brevispinum YELLOW PINK TILL BROWNISH PECTINATE SPINES , GREEN SILVER BODY/ ACANTHOCALYCIUM KP 236 Road Santa Maria to Cafayate alt. 1685 m , p. Salta , Argentina 0,08 € 2,00 Kč 0,20 € 5,00 Kč 1,60 € 40,00 Kč pectinate pink brown spines , large light yellow flower , violet stigma / VY-013589-A VY-013589-B VY-013589-C peitscherianum Backeb. -

Cacti, Biology and Uses

CACTI CACTI BIOLOGY AND USES Edited by Park S. Nobel UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2002 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cacti: biology and uses / Park S. Nobel, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-520-23157-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Cactus. 2. Cactus—Utilization. I. Nobel, Park S. qk495.c11 c185 2002 583'.56—dc21 2001005014 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 10 987654 321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). CONTENTS List of Contributors . vii Preface . ix 1. Evolution and Systematics Robert S. Wallace and Arthur C. Gibson . 1 2. Shoot Anatomy and Morphology Teresa Terrazas Salgado and James D. Mauseth . 23 3. Root Structure and Function Joseph G. Dubrovsky and Gretchen B. North . 41 4. Environmental Biology Park S. Nobel and Edward G. Bobich . 57 5. Reproductive Biology Eulogio Pimienta-Barrios and Rafael F. del Castillo . 75 6. Population and Community Ecology Alfonso Valiente-Banuet and Héctor Godínez-Alvarez . 91 7. Consumption of Platyopuntias by Wild Vertebrates Eric Mellink and Mónica E. Riojas-López . 109 8. Biodiversity and Conservation Thomas H. Boyle and Edward F. Anderson . 125 9. Mesoamerican Domestication and Diffusion Alejandro Casas and Giuseppe Barbera . 143 10. Cactus Pear Fruit Production Paolo Inglese, Filadelfio Basile, and Mario Schirra . -

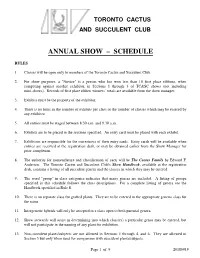

Annual Show – Schedule

TORONTO CACTUS AND SUCCULENT CLUB ANNUAL SHOW – SCHEDULE RULES 1. Classes will be open only to members of the Toronto Cactus and Succulent Club. 2. For show purposes, a "Novice" is a person who has won less than 10 first place ribbons, when competing against another exhibitor, in Sections 1 through 3 of TC&SC shows (not including mini-shows). Records of first place ribbon winners’ totals are available from the show manager. 3. Exhibits must be the property of the exhibitor. 4. There is no limit in the number of exhibits per class or the number of classes which may be entered by any exhibitor. 5. All entries must be staged between 8:30 a.m. and 9:30 a.m. 6. Exhibits are to be placed in the sections specified. An entry card must be placed with each exhibit. 7. Exhibitors are responsible for the correctness of their entry cards. Entry cards will be available when entries are received at the registration desk, or may be obtained earlier from the Show Manager for prior completion. 8. The authority for nomenclature and classification of cacti will be The Cactus Family by Edward F. Anderson. The Toronto Cactus and Succulent Club's Show Handbook , available at the registration desk, contains a listing of all succulent genera and the classes in which they may be entered. 9. The word "group" in class categories indicates that many genera are included. A listing of groups specified in this schedule follows the class descriptions. For a complete listing of genera see the Handbook specified in Rule 8. -

From Cacti to Carnivores: Improved Phylotranscriptomic Sampling And

Article Type: Special Issue Article RESEARCH ARTICLE INVITED SPECIAL ARTICLE For the Special Issue: Using and Navigating the Plant Tree of Life Short Title: Walker et al.—Phylotranscriptomic analysis of Caryophyllales From cacti to carnivores: Improved phylotranscriptomic sampling and hierarchical homology inference provide further insight into the evolution of Caryophyllales Joseph F. Walker1,13, Ya Yang2, Tao Feng3, Alfonso Timoneda3, Jessica Mikenas4,5, Vera Hutchison4, Caroline Edwards4, Ning Wang1, Sonia Ahluwalia1, Julia Olivieri4,6, Nathanael Walker-Hale7, Lucas C. Majure8, Raúl Puente8, Gudrun Kadereit9,10, Maximilian Lauterbach9,10, Urs Eggli11, Hilda Flores-Olvera12, Helga Ochoterena12, Samuel F. Brockington3, Michael J. Moore,4 and Stephen A. Smith1,13 Manuscript received 13 October 2017; revision accepted 4 January 2018. 1 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, 830 North University Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1048 USA 2 Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, 1445 Gortner Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55108 USA 3 Department of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EA, UK 4 Department of Biology, Oberlin College, Science Center K111, 119 Woodland Street, Oberlin, OH 44074-1097 USA 5 Current address: USGS Canyonlands Research Station, Southwest Biological Science Center, 2290 S West Resource Blvd, Moab, UT 84532 USA 6 Institute of Computational and Mathematical Engineering (ICME), Stanford University, 475 Author Manuscript Via Ortega, Suite B060, Stanford, CA, 94305-4042 USA This is the author manuscript accepted for publication and has undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. -

A Taxonomic Backbone for the Global Synthesis of Species Diversity in the Angiosperm Order Caryophyllales

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 A taxonomic backbone for the global synthesis of species diversity in the angiosperm order Caryophyllales Hernández-Ledesma, Patricia; Berendsohn, Walter G; Borsch, Thomas; Mering, Sabine Von; Akhani, Hossein; Arias, Salvador; Castañeda-Noa, Idelfonso; Eggli, Urs; Eriksson, Roger; Flores-Olvera, Hilda; Fuentes-Bazán, Susy; Kadereit, Gudrun; Klak, Cornelia; Korotkova, Nadja; Nyffeler, Reto; Ocampo, Gilberto; Ochoterena, Helga; Oxelman, Bengt; Rabeler, Richard K; Sanchez, Adriana; Schlumpberger, Boris O; Uotila, Pertti Abstract: The Caryophyllales constitute a major lineage of flowering plants with approximately 12500 species in 39 families. A taxonomic backbone at the genus level is provided that reflects the current state of knowledge and accepts 749 genera for the order. A detailed review of the literature of the past two decades shows that enormous progress has been made in understanding overall phylogenetic relationships in Caryophyllales. The process of re-circumscribing families in order to be monophyletic appears to be largely complete and has led to the recognition of eight new families (Anacampserotaceae, Kewaceae, Limeaceae, Lophiocarpaceae, Macarthuriaceae, Microteaceae, Montiaceae and Talinaceae), while the phylogenetic evaluation of generic concepts is still well underway. As a result of this, the number of genera has increased by more than ten percent in comparison to the last complete treatments in the Families and genera of vascular plants” series. A checklist with all currently accepted genus names in Caryophyllales, as well as nomenclatural references, type names and synonymy is presented. Notes indicate how extensively the respective genera have been studied in a phylogenetic context. -

The Genus Pterocactus

The Genus Pterocactus Elisabeth & Norbert Sarnes © 2020 Distribution of Pterocacti Species Described Species Pterocactus araucanus Pterocactus australis Pterocactus fischeri Pterocactus gonjianii Pterocactus hickenii (syn. skottsbergii) Pterocactus megliolii Pterocactus neuquensis Pterocactus reticulatus Pterocactus valentinii ( syn. pumilus) Pterocactus tuberosus (syn. decipiens, kuntzei) Undescribed Species Pterocactus sp. „Fiambala“ Pterocactus sp. „Rosada“ Pterocactus sp. „Spiny“ Distribution of Pterocactus araucanus Pterocactus araucanus is typically found near the town of Gualjaina in the province of Chubut (With a little luck, you can already recognize a few plants on the photo.) Pterocactus araucanus Distribution of Pterocactus australis Pterocactus australis, occurs, for example, at such levels on the edge of Lake Viedma in the province of Santa Cruz. Pterocactus australis near the town of Fitz Roy in the province of Santa Cruz Distribution of Pterocactus fischeri Typical landscape of Pterocactus fischeri near Castillos de Pincheira, Mendoza. Pterocactus fischeri near Termas El Sosneado, Mendoza. Distribution of Pterocactus gonjianii Typical landscape of Pterocactus gonjianii at the Agua Negra Pass, San Juan. Pterocactus gonjianii near Alto Jagüe, La Rioja. Distribution of Pterocactus hickenii Typical landscape of Pterocactus hickenii near Rio Mayo, Chubut. Pterocactus hickenii at Las Heras, Santa Cruz. Distribution of Pterocactus megliolii The home of Pterocactus megliolii near La Laja, San Juan. Pterocactus megliolii near Baños La Laja, San Juan. Distribution of Pterocactus neuquensis Typical landscape of Pterocactus neuquensis sputh of Zapala , Neuquen. Spiny plant of Pterocactus neuquensis near the Arroyo Carreri, west of the city of Zapala, Neuquen. Distribution of Pterocactus reticulatus Here, on these plains north of the town of Uspallata in the province of Mendoza, Pterocactus reticulatus is at home. -

Pterocactus Jewels of the Cono Sur

Pterocactus Jewels of the Cono Sur Elisabeth & Norbert Sarnes Cono Sur = Southern Cone The 'Southern Cone' refers to the southern tip of South America below the tropic of Capricorn. 2 Elisabeth & Norbert Sarnes Pterocactus Jewels of the Cono Sur 3 Pterocactus Jewels of the Cono Sur Herausgeber: Elisabeth & Norbert Sarnes Viktoriastr. 3 52249 Eschweiler Deutschland mail: [email protected] Fotos: Unless otherwise stated, by Elisabeth & Norbert Sarnes Copyright: 2021, Elisabeth & Norbert Sarnes The distribution maps were created using the Vasco Da Gama software and the Digital World Map by Motion-Studios (www.motionstudios.de). Any use, in particular copying, editing, translation, microfilming, distribution, and processing in electronic systems - unless expressly permitted by copy- right law - requires the consent of the publishers. Our thanks go to Wolfgang Borgmann for his willingness to proofread our texts and for his helpful advice. We thank Graham Charles for proofreading and making our English more understandable. 4 Contents Preface …………………………………………………… 6 Introduction …………………………………………………… 8 The genus Pterocactus ……………………………. 10 Pterocactus araucanus ……………………………. 14 Pterocactus australis ……………………………. 20 Ptercactus fischeri ……………………………. 26 Pterocactus gonjianii ……………………………. 32 Pterocactus hickenii ……………………………. 36 Pterocactus megliolii ……………………………. 42 Pterocactus neuquensis ……………………………. 46 Pterocactus reticulatus ……………………………. 52 Pterocactus skottsbergii ……………………………. 56 Pterocactus tuberosus ……………………………. 62 Pterocactus valentinii