Ireland and the Celtic Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol.117C, Pp.65-99

Gleeson P. (2017) Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, vol.117C, pp.65-99. Copyright: This is the author’s accepted manuscript of an article that has been published in its final definitive form by the Royal Irish Academy, 2017. Link to article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3318/priac.2017.117.04 Date deposited: 07/04/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Luigne Breg and the origins of the Uí Néill By Patrick Gleeson, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University Email: [email protected] Phone: (+44) 01912086490 Abstract: This paper explores the enigmatic kingdom of Luigne Breg, and through that prism the origins and nature of the Uí Néill. Its principle aim is to engage with recent revisionist accounts of the various dynasties within the Uí Néill; these necessitate a radical reappraisal of our understanding of their origins and genesis as a dynastic confederacy, as well as the geo-political landsape of the central midlands. Consequently, this paper argues that there is a pressing need to address such issues via more focused analyses of local kingdoms and political landscapes. Holistic understandings of polities like Luigne Breg are fundamental to framing new analyses of the genesis of the Uí Néill based upon interdisciplinary assessments of landscape, archaeology and documentary sources. In the latter part of the paper, an attempt is made to to initiate a wider discussion regarding the nature of kingdoms and collective identities in early medieval Ireland in relation to other other regions of northwestern Europe. -

Minerals Development Acts, 1940–1999

MINERALS DEVELOPMENT ACTS, 1940–1999 Report by the Minister of the Environment, Climate and Communications for the six months ended 30 June 2021 In accordance with Section 77 of the Minerals Development Act, 1940 And Section 8 of the Minerals Development Act, 1979 Prepared by the Geoscience Regulation Office Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications www.gov.ie/decc Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications Minerals Development Acts, 1940-1999 Report by the Minister for the Environment, Climate and Communications for the six months ended 30 June 2021 In accordance with Section 77 of the Minerals Development Act, 1940 and Section 8 of The Minerals Development Act, 1979 Geoscience Regulation Office Minerals Production MP 04/21 _______________________________________ Dublin Published by the Stationery Office To be purchased from Government Publications 52 St. Stephen's Green, Dublin, D02 DR67. (Tel: 076 1106 834 or Email: [email protected]) or through any bookseller. This report may also be found on the Internet at www.gov.ie where it was posted shortly after it’s presentation to the Oireachtas _______________________________________ Sale Price: €12.70 © Government of Ireland 2021 An Roinn Comhshaoil, Aeráide agus Cumarsáide Na hAchtanna Forbartha Mianraí, 1940-1999 Tuarascáil an Aire Comhshaoil, Aeráide agus Cumarsáide don sé mhí dár críoch 30 Meitheamh 2021 De réir Alt 77 den Acht Forbairte Mianraí, 1940 agus Alt 8 den Acht Forbartha Mianraí, 1979 Oifig Rialacháin Geo-Eolaíochta Táirgeadh Mianraí MP 04/21 _______________________________________ Baile Átha Cliath Arna Fhoilsiú ag Oifig an tSoláthair Le ceannach díreach ó Foilseacháin Rialtais 52 Faiche Stiabhna, Baile Átha Cliath, D02 DR67. -

Indiana University at Bloomington Official Lists of Graduates And

Indiana University at Bloomington Official Lists of Graduates and Honors Recipients 2018 - 2019 Dates Degrees Conferred June 30, 2018 July 27, 2018 August 18, 2018 August 31, 2018 September 30, 2018 October 31, 2018 November 8, 2018 November 30, 2018 December 15, 2018 January 31, 2019 February 14, 2019 February 28, 2019 March 31, 2019 April 30, 2019 May 3, 2019 May 4, 2019 May 9, 2019 1 ** DEGREE LISTINGS FOR STUDENTS WITH COMPLETE RESTRICTIONS ARE EXCLUDED FROM THE RELEASED OFFICIAL LIST OF GRADUATES ** 2 June Business June Business June Business B. S. in Business B. S. in Business B. S. in Business Aisen, Ari Nathaniel Eckhart, John C., Jr. Kuster, Samuel Marketing Finance Finance Accounting BEPP: Economic Consulting Armstrong, Kayla Nicole Business Analytics Accounting Levens, Julia Anne Technology Management Folsom, Anna Accounting Finance Finance Barco, Clark Tobias, Jr. Accounting With High Distinction Accounting With Honors in Business International Business Lifvendahl, Axel Thomas With High Distinction Foster, James Dean Marketing Accounting Borders, Ryan Harrison Information Systems Lin, Bonnie Professional Sales Accounting Marketing Fu, Weiying Finance Accounting Burton, La'Shira Aretha Technology Management Lisanti, Annabelle Leigh Accounting BEPP: Economic Consulting Ganas, Nicholas Apostolos International Business Bush, Quinn Andrew Finance Accounting International Business Liu, Jiawei Finance With High Distinction Accounting International Business With Honors in Business Technology Management Cheng, Hung Kit George, Mikaela -

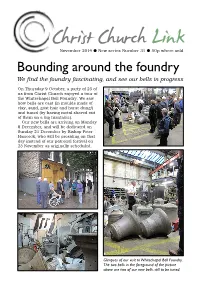

Bounding Around the Foundry We Find the Foundry Fascinating, and See Our Bells in Progress

Christ Church Link November 2014 l New series Number 31 l 50p where sold Bounding around the foundry We find the foundry fascinating, and see our bells in progress On Thursday 9 October, a party of 25 of us from Christ Church enjoyed a tour of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. We saw how bells are cast (in moulds made of clay, sand, goat hair and horse dung!) and tuned (by having metal shaved out of them on a big turntable). Our new bells are arriving on Monday 8 December, and will be dedicated on Sunday 21 December by Bishop Peter Hancock, who will be presiding on that day instead of our patronal festival on 23 November as originally scheduled. Glimpses of our visit to Whitechapel Bell Foundry. The two bells in the foreground of the picture above are two of our new bells, still to be tuned. Improving access Mothers’ Union news Sylvia Ayers writes: Have YOU bought your MU Christmas Cards yet?? A colourful poster depicting them all is on the MU noticeboard, and, as with all good things, the early bird catches the worm. As usual, the cards come in packs of 10, so late ordering or a shortage of supplies may result in you missing out on a favourite choice. Do let Sylvia have your “cash with order” now if you would like to take advantage of our seasonal offer. Both Canon Angela and Margaret would like to thank everyone for their support at the MU Indoor Members’ Communion Service on October 17th, which ranged from welcoming our visitors to serving the refreshments, a task at which Angela (Verger) is particularly good! Both this and the meeting with our World-Wide President Lynn Temby at Monkton Combe School on 22nd, are very important events in the MU Calendar, so we thank everyone for their attendance and interest. -

1 Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1St

Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1st January 2020 Holy Name of Jesus Circumcision of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea of Palestine, Father of the Church (379) Beoc of Lough Derg, Donegal (5th or 6th c.) Connat, Abbess of St. Brigid’s convent at Kildare, Ireland (590) Ossene of Clonmore, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 3:10-19 Eph 3:1-7 Lk 6:5-11 Holy Name of Jesus: ♦ Vespers: Ps 8 and 19 ♦ 1st Nocturn: Ps 64 1Tm 2:1-6 Lk 6:16-22 ♦ 3rd Nocturn: Ps 71 and 134 Phil 2:6-11 ♦ Matins: Jn 10:9-16 ♦ Liturgy: Gn 17:1-14 Ps 112 Col 2:8-12 Lk 2:20-21 ♦ Sext: Ps 53 ♦ None: Ps 148 1 Thursday 2 January 2020 Seraphim, priest-monk of Sarov (1833) Adalard, Abbot of Corbie, Founder of New Corbie (827) John of Kronstadt, priest and confessor (1908) Seiriol, Welsh monk and hermit at Anglesey, off the coast of north Wales (early 6th c.) Munchin, monk, Patron of Limerick, Ireland (7th c.) The thousand Lichfield Christians martyred during the reign of Diocletian (c. 333) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:1-6 Eph 3:8-13 Lk 8:24-36 Friday 3 January 2020 Genevieve, virgin, Patroness of Paris (502) Blimont, monk of Luxeuil, 3rd Abbot of Leuconay (673) Malachi, prophet (c. 515 BC) Finlugh, Abbot of Derry (6th c.) Fintan, Abbot and Patron Saint of Doon, Limerick, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:7-14a Eph 3:14-21 Lk 6:46-49 Saturday 4 January 2020 70 Disciples of Our Lord Jesus Christ Gregory, Bishop of Langres (540) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:14b-20 Eph 4:1-16 Lk 7:1-10 70 Disciples: Lk 10:1-5 2 Sunday 5 January 2020 (Forefeast of the Epiphany) Syncletica, hermit in Egypt (c. -

The Survival of the Confraternities in Post-Reformation Dublin

The Survival of the Confraternities in Post-Reformation Dublin COLM LENNON St. Patrick 's College, Maynooth When the Reformation came to Dublin in the 1530s it might have seemed as if the age of the confraternities or religious guilds of the city was over. As elsewhere in Europe, these institutions provided conduits for obituar- ial prayer for members and their families, welfare for the deprived, education for the young, and pomp and pageantry for citizens during the civic year. Handsomely endowed with gifts of money, lands and houses, the guilds gave employment to an increasing number of lay-ap- pointed chaplains who celebrated mass at the confraternal altars in the parish churches of Dublin. By the early sixteenth century the guilds had acquired the titles to properties yielding hundreds of pounds per annum in rents from estates in the city, suburbs and vicinity. Membership incorporated men and women from all social orders within the munici- pality, although the preponderance of patrician brothers and sisters in certain key guilds such as those of St. Sythe's in St. Michan's, St. Anne's in St. Audoen's and Corpus Christi in St. Michael's parish was to be a significant feature of their later survival into the seventeenth century. Con- tinuity with medieval devotions was enshrined in the practices and pieties of the guilds, those of St. George and St. Mary's, Mulhuddard, providing an awning for holy wells to the east and west of the city, for example, and the fresco behind the altar of St. Anne's denoting veneration of the holy family. -

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal Ágnes Juhász-Ormsby The Episcopal Library of St. John’s is among the few nineteenth- century libraries that survive in their original setting in the Atlantic provinces, and the only one in Newfoundland and Labrador.1 It was established by John Thomas Mullock (1807–69), Roman Catholic bishop of Newfoundland and later of St. John’s, who in 1859 offered his own personal collection of “over 2500 volumes as the nucleus of a Public Library.” The Episcopal Library in many ways differs from the theological libraries assembled by Mullock’s contemporaries.2 When compared, for example, to the extant collection of the Catholic bishop of Victoria, Charles John Seghers (1839–86), whose life followed a similar pattern to Mullock’s, the division in the founding collection of the Episcopal Library between the books used for “private” as opposed to “public” theological study becomes even starker. Seghers’s books showcase the customary stock of a theological library with its bulky series of manuals of canon law, collections of conciliar and papal acts and bullae, and practical, dogmatic, moral theological, and exegetical works by all the major authors of the Catholic tradition.3 In contrast to Seghers, Mullock’s library, although containing the constitutive elements of a seminary library, is a testimony to its found- er’s much broader collecting habits. Mullock’s books are not restricted to his philosophical and theological studies or to his interest in univer- sal church history. They include literary and secular historical works, biographies, travel books, and a broad range of journals in different languages that he obtained, along with other necessary professional 494 newfoundland and labrador studies, 32, 2 (2017) 1719-1726 John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal tools, throughout his career. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

Bygone Church Life in Scotland

*«/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GIFT OF Old Authors Farm Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/bygonechurchlifeOOandrrich law*""^""*"'" '* BYGONE CHURCH LIFE IN SCOTLAND. 1 f : SS^gone Cburcb Xife in Scotland) Milltam Hnbrewa . LONDON WILLIAM ANDREWS & CO., 5. FARRINGDON AVENUE, E.G. 1899. GIFT Gl f\S2S' IPreface. T HOPE the present collection of new studies -*- on old themes will win a welcome from Scotsmen at home and abroad. My contributors, who have kindly furnished me with articles, are recognized authorities on the subjects they have written about, and I think their efforts cannot fail to find favour with the reader. V William Andrews. The HuLl Press, Christmas Eve^ i8g8. 595 Contents. PAGE The Cross in Scotland. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. i Bell Lore. By England Hewlett 34 Saints and Holy Wells. By Thomas Frost ... 46 Life in the Pre-Reformation Cathedrals. By A. H. Millar, F.S.A., Scot 64 Public Worship in Olden Times. By the Rev. Alexander Waters, m.a,, b.d 86 Church Music. By Thomas Frost 98 Discipline in the Kirk. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. 108 Curiosities of Church Finance. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 130 Witchcraft and the Kirk. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 162 Birth and Baptisms, Customs and Superstitions . 194 Marriage Laws and Customs 210 Gretna Green Gossip 227 Death and Burial Customs and Superstitions . 237 The Story of a Stool 255 The Martyrs' Monument, Edinburgh .... 260 2 BYGONE CHURCH LIFE. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Religious Studies

RELIGIOUS STUDIES Religious Studies The Celtic Church in Ireland in the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Centuries Unit AS 5 Content/Specification Section Page The Arrival of Christianity in Ireland 2 Evidence for the presence of Christianity in Ireland before the arrival of St. Patrick 6 Celtic Monasticism 11 Celtic Penitentials 17 Celtic Hagiography 21 Other Aspects of Human Experience Section 25 Glossary 42 RELIGIOUS STUDIES The Arrival of Christianity in Ireland © LindaMarieCaldwell/iStock/iStock/Thinkstock.com Learning Objective – demonstrate knowledge and understanding of, and critically evaluate the background to the arrival of Christianity in Ireland, including: • The political, social and religious background; • The arrival of and the evidence for Christianity in Ireland before Patrick; and • The significance of references to Palladius. This section requires students to explore: 1. The political, social and religious background in Ireland prior to the arrival of Christianity in Ireland. 2. Evidence of the arrival of Christianity in Ireland before Patrick (Pre-Patrician Christianity. 3. References to Palladius and the significance of these references to understanding the background to Christianity in Ireland before Patrick’s arrival. Early Irish society provided a great contrast to the society of the Roman Empire. For example, it had no towns or cities, no central government or no standard currency. Many Scholars have described it as tribal, rural, hierarchical and familiar. The Tuath was the basic political group or unit and was a piece of territory ruled by a King. It is estimated that there were about 150 such Tuath in pre – Christian Ireland. The basic social group was the fine and included all relations in the male line of descent.