TICCIH Bulletin No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Council Session

SOUTH ATLANTIC FISHERY MANAGEMENT COUNCIL FULL COUNCIL SESSION Hilton Garden Inn/Outer Banks Kitty Hawk, North Carolina December 6-7, 2018 Summary Minutes Council Members Jessica McCawley, Chair Mel Bell, Vice-Chair Anna Beckwith Chester Brewer Dr. Kyle Christiansen Chris Conklin Dr. Roy Crabtree Tim Griner Doug Haymans Dr. Wilson Laney LCDR Jeremy Montes Stephen Poland Art Sapp David Whitaker Spud Woodward Council Staff Gregg Waugh John Carmichael Dr. Brian Cheuvront Myra Brouwer Dr. Chip Collier Dr. Mike Errigo John Hadley Kathleen Howington Kim Iverson Kelly Klasnick Roger Pugliese Cameron Rhodes Amber Von Harten Christian Wiegand Julia Byrd Mike Collins Observers and Participants Rick DeVictor Nik Mehte Shep Grimes Erika Burgess Dr. Jack McGovern Monica Smith-Brunello Dr. Clay Porch Dr. Erik Williams Tony Dilernia Dale Diaz Charlie Phillips Michael Larkin Brett Pierce Vivian Matter Heather Coleman Kelley Elliott Full Council Session December 6-7, 2018 Kitty Hawk, NC The Full Council Session of the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council convened at the Hilton Garden Inn/Outer Banks, Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on Thursday afternoon, December 6, 2018, and was called to order by Chairman Jessica McCawley. MS. MCCAWLEY: We are going to move into Full Council. We need to go around the table and do voice identification, and we’ll start over there with Spud. MR. WOODWARD: Spud Woodward. DR. CHRISTIANSEN: Kyle Christiansen. MR. HAYMANS: Doug Haymans, Georgia. MR. SAPP: Art Sapp. MR. BREWER: Chester Brewer, Florida. MR. WHITAKER: David Whitaker, South Carolina. MR. BELL: Mel Bell, South Carolina. MR. CONKLIN: Christopher Conklin, South Carolina. DR. LANEY: Wilson Laney, Fish and Wildlife Service. -

Seattle 2015

Peripheries and Boundaries SEATTLE 2015 48th Annual Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology January 6-11, 2015 Seattle, Washington CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS (Our conference logo, "Peripheries and Boundaries," by Coast Salish artist lessLIE) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 01 – Symposium Abstracts Page 13 – General Sessions Page 16 – Forum/Panel Abstracts Page 24 – Paper and Poster Abstracts (All listings include room and session time information) SYMPOSIUM ABSTRACTS [SYM-01] The Multicultural Caribbean and Its Overlooked Histories Chairs: Shea Henry (Simon Fraser University), Alexis K Ohman (College of William and Mary) Discussants: Krysta Ryzewski (Wayne State University) Many recent historical archaeological investigations in the Caribbean have explored the peoples and cultures that have been largely overlooked. The historical era of the Caribbean has seen the decline and introduction of various different and opposing cultures. Because of this, the cultural landscape of the Caribbean today is one of the most diverse in the world. However, some of these cultures have been more extensively explored archaeologically than others. A few of the areas of study that have begun to receive more attention in recent years are contact era interaction, indentured labor populations, historical environment and landscape, re-excavation of colonial sites with new discoveries and interpretations, and other aspects of daily life in the colonial Caribbean. This symposium seeks to explore new areas of overlooked peoples, cultures, and activities that have -

Over the Range

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Over the Range Richard V. Francaviglia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Francaviglia, R. V. (2008). Over the range: A history of the Promontory Summit route of the Pacific ailrr oad. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Over the Range Photo by author Photographed at Promontory, Utah, in 2007, the curving panel toward the rear of Union Pacifi c 119’s tender (coal car) shows the colorful and ornate artwork incorporated into American locomotives in the Victorian era. Over the Range A History of the Promontory Summit Route of the Pacifi c Railroad Richard V. Francaviglia Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright ©2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7200 www.usu.edu/usupress Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on recycled, acid-free paper ISBN: 978-0-87421-705-6 (cloth) ISBN: 978-0-87421-706-3 (e-book) Manufactured in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Francaviglia, Richard V. Over the range : a history of the Promontory summit route of the Pacifi c / Richard V. Francaviglia. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-87421-705-6 (cloth : alk. -

Newsletter 74

ROYAL NAVAL PATROL SERVICE ASSOCIATION ________ NEWSLETTER No. 74 Spring 2013 _________ POSTAL ADDRESS and HEADQUARTERS Royal Naval Patrol Service Association Naval Museum, Sparrows Nest, Lowestoft, Suffolk NR32 1XG Charity No. 273148 Tel: 01502 586250 E-mail: [email protected] Well that was a winter and a half, it must have liked us because it did not want to go. We have at last seen a few sunny days but nothing as yet to convince us that we are going to have a good summer. Perhaps it is saving itself for our reunion weekend so we can be in shirt sleeve order. In this edition you will find the details and booking form for the reunion in October when we hope to see as many of you as possible. Reunion 2013 So, the programme for the reunion is - 1. Friday 4th October, the AGM will be held at the Trinity Methodist Church, Park Road at 1.30. 2. The annual Dinner will be held on Friday 4th at the Ambassador Suite, The Hatfield Hotel, Lowestoft, 6.30 for 7.00 and the cost will be the same as last year, £23 per head. There will be no coach transport due to the costs but there is a small car park opposite plus street parking. See booking form at the end of the newsletter to make your menu choice and please get it back to us early as preference will be given to RNPS veterans. 3. The service of remembrance will be at 11.00 on Sat. 5th Oct. (muster 10.45) in Belle Vue Park. -

Shipwreck of the USS Monitor

WWII Offshore: Monitor National Marine Sanctuary’s Battle of the Atlantic Expedition John Wagner Maritime Archaeologist Monitor National Marine Sanctuary April 11, 2013 America’s First National Marine Sanctuary: Shipwreck of the USS Monitor -The Monitor National Marine Sanctuary was established by Congress on January 30, 1975, on the 113th Anniversary of the Monitor’s launching at Greenpoint, NY. World War II Naval History Significance of North Carolina • Shipping Lanes • Oceanic Currents • Continental Shelf • Water Depth • Water Temperatures Analysis of Battle-Related Events Battle of the Atlantic Expedition Promoting the Protection of Maritime Heritage in North Carolina 2008-2013 Year One: Examining Damages to German U-boats and Developing Baseline Data Sites Surveyed: • U-85 • U-352 • U-701 U-85 Shipwreck Lost April 14, 1942 U-352 Shipwreck Lost May 9, 1942 U-701 Shipwreck Lost July 7, 1942 Baseline Offset Recording Survey Products U-85 U-352 Site Plan Drafting Site Plans Year Two: Documenting US and Allied Military Losses Stage One: Deep Water Multibeam Sonar Survey Site Surveyed: • USS YP-389 Multibeam sonar survey during which USS YP-389 was relocated and identified Researchers Deploying the ROV above the site of USS YP-389 Photo-Mosaic of USS YP-389 How did we determine the vessel found was YP-389? • Archival Research (photos and documents) • Location • Vessel Type and Size •Armament 3-inch .23-caliber boat gun YP-389 Porthole Stage Two: Diving Survey Site Surveyed: • HMT Bedfordshire Lost May 12, 1942 Wreckage at the HMT Bedfordshire Site Monitoring U-boats: Corrosion Potential Analysis Year Three: Documenting US and Allied Merchant Marine Losses Stage One: Technical Diving Photographic and Videographic Survey as well as Biological Transects Sites Surveyed: • City of Atlanta • Dixie Arrow • E. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: HMT BEDFORDSHIRE (shipwreck and remains) Other names/site number: BEDFORDSHIRE, HMS BEDFORDSHIRE Name of related multiple property listing: ____ World War II Shipwrecks along the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico__________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _Offshore____________________________________________ City or town: Offshore-Beaufort State: Offshore-NC County: Offshore-Carteret Not For Publication: Vicinity: x ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties -

The Value of Maritime Archaeological Heritage

THE VALUE OF MARITIME ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF THE CULTURAL CAPITAL OF SHIPWRECKS IN THE GRAVEYARD OF THE ATLANTIC by Calvin H. Mires April 2014 Director of Dissertation: Dr. Nathan Richards Ph.D. Program in Coastal Resources Management Off the coast of North Carolina’s Outer Banks are the remains of ships spanning hundreds of years of history, architecture, technology, industry, and maritime culture. Potentially more than 2,000 ships have been lost in “The Graveyard of the Atlantic” due to a combination of natural and human factors. These shipwrecks are tangible artifacts to the past and constitute important archaeological resources. They also serve as dramatic links to North Carolina’s historic maritime heritage, helping to establish a sense of identity and place within American history. While those who work, live, or visit the Outer Banks and look out on the Graveyard of the Atlantic today have inherited a maritime heritage as rich and as historic as any in the United States, there is uncertainty regarding how they perceive and value the preservation of maritime heritage resources along the Outer Banks, specifically shipwrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic. This dissertation is an exploratory study that combines qualitative and quantitative methodologies from the fields of archaeology, economics, and sociology, by engaging different populations in a series of interviews and surveys. These activities are designed to understand and evaluate the public’s current perceptions and attitudes towards maritime archaeological heritage, to estimate its willingness to pay for preservation of shipwrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic, and to provide baseline data for informing future preservation, public outreach, and education efforts. -

Parading the PWSTS Standard in Ocracoke /Buxton NC USA 11/12 May 2017

Parading the PWSTS Standard in Ocracoke /Buxton NC USA 11/12 May 2017 The PWSTS Standard was successfully paraded at two local commemorative services to British seamen at Ocracoke and Buxton, North Carolina, USA on 11th and 12th May, 2017 and was pleasantly welcomed by all although, not unexpectedly, with a little puzzlement too as to why as it was a long way from home. However, I was given every encouragement to join both ceremonies and thoroughly welcomed to participate in the services at both locations and enjoyed wonderful hospitality from all. My original aim was only to attend the Ocracoke service of remembrance to the lost crew of HMT Bedfordshire, being one of the Royal Naval Patrol Service‟s anti-submarine trawlers sent to the east coast of America in 1942 to protect the merchant vessels heading north along that coast to form the Atlantic convoys at Halifax, Nova Scotia, but I soon discovered that nearby at Buxton, Cape Hatteras there was another small cemetery containing just two graves, one an unknown seaman and the other, 4th Engineer Michael Cairns of the San Delfino, a British tanker carrying aviation fuel that was torpedoed and sunk at the end of April, 1942 that, being specifically MN, I felt I must visit. Here I intended to lay one of the two wreathes brought from England and expected to do this quietly on my own but discovered that the day before the ceremony at Ocracoke an official service was also being held at Buxton so I travelled back a few miles for that. -

Virginia City) in the Development of the 1960S Psychedelic Esthetic and “San Francisco Sound"

University of Nevada, Reno Rockin’ the Comstock: Exploring the Unlikely and Underappreciated Role of a Mid-Nineteenth Century Northern Nevada Ghost Town (Virginia City) in the Development of the 1960s Psychedelic Esthetic and “San Francisco Sound" A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Engrid Barnett Dr. Paul F. Starrs/Dissertation Advisor May 2014 © Copyright by Engrid Barnett, 2014 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Engrid Barnett entitled Rockin’ the Comstock: Exploring the Unlikely and Underappreciated Role of a Mid-Nineteenth Century Northern Nevada Ghost Town (Virginia City) in the Development of the 1960s Psychedelic Esthetic and "San Francisco Sound" be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Paul Starrs, PhD, Advisor and Committee Chair Donald Hardesty, PhD, Committee Member Alicia Barber, PhD, Committee Member Jill S. Heaton, PhD, Committee Member David Ake, PhD, Graduate School Representative Marsha H Read, PhD, Dean of the Graduate School May 2014 i ABSTRACT Virginia City, Nevada, epitomized and continues to epitomize a liminal community — existing on the very limen of the civilized and uncivilized, legitimate and illegitimate, parochial frontier and cosmopolitan metropolis. Throughout a 150-year history, its thea- ters attracted performers of national and international acclaim who entertained a diverse civic population -

Summer 2017 News Letter

Volume IV Issue 2 Summer Edition — July 2017 Official Publication of the United States Coast Guard Pipe Band www.uscgpipeband.org * Active * Reserve * Retired * CG Veterans * Auxiliary * In this Issue Declaration of Independence • Letter from the Pipe Major • British War Graves Many of you will be busy in the coming week with Independence Day celebrations all around the nation. As you take part in the festivities, don’t forget what we’re • National LE Week truly celebrating; it’s more than a date on a calendar. As you stand proudly this • Disabled Veterans Memorial weekend, let the Declaration of Independence ring in your mind: • Commodore’s Banquet “When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for • Featured Shipmate one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the • New OPS Boss Earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature • Crossing the Bar and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the causes • LT Doria Retires which impel them to the separation.” • Awards and Recognition “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they • Welcome Aboard / Fair Winds are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are • Updated “For Sale” Board Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness - That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the Consent of • And more.. -

DOCTRINE Leonard Smith, Dean of Stu- R

DEAN SMITH EXTENDS CONGRATULATIONS TO 195 MCC STUDENTS DOCTRINE Leonard Smith, Dean of Stu- R. Johnson, B. Jones, G. Ka- dents, has recently announced leta, J. Kaplan, C. Karwacki, K. that 195 students attained a 3.00 Kellogg, A. Kendig, V. Keppler, Volume IV March 7, 1966, Rochester, N. Y. No. 9 average or better during the first G. Kernutt, B. Kinzel, B. Kla- semester and thus have been witter, J. Knitis, B. Knitter, S. named on the Dean's List. Kopin, M. Koutz, T. Kraus, L. Krinsky, V. Krivis, B. La Varn- PROFESSOR SPEAKS Cultural Those students are: way, B. Lambert, J. Lauth, D. C. Allen, T. Allen, S. Amazeen, Leach, R. Lindeman, B. Lloyd, J. Ange, J. Astman, R. Backer, P. Lloyd, W. Long, P. Longdue, ON STUDENT REBELS Events M. Bader, P. Baker, R. Bartucca, C. Loria, D. Love, R. Lux, V. E. Bemish, H. Benson, F. Bi- Lynd. By BRUCE KNIGHT "chalk up the war in Vietnam to anchi, G. Bitetti, S. Bitkoff, G. the poor." J. Marcille, P. Margeson, E. On Friday, February 18th, Prof. Blake, O. Blyszczak, T. Boland, Mayes, J. McNall, L. Menter, J. Richard O'Keefe delivered the Democracy stresses equality, Schedule G. Bookmiller, B. Braddock, M. education and responsibility in Meyer, L. Millard, D. Moore, S. first of four planned faculty lec- Everything on this schedule is Brown, R. Budic, N. Burnett, J. Morley, J. Muck, D. Nagel, P. tures. He spoke on the topical, fellow man, but the system free to MCC students. Tickets Butterfield. O'Sullivan, J. Otis, L. -

Newsletter 82

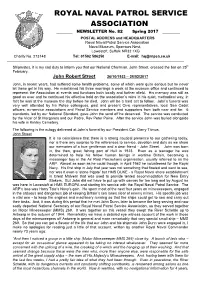

ROYAL NAVAL PATROL SERVICE ASSOCIATION ________ NEWSLETTER No. 82 Spring 2017 _________ POSTAL ADDRESS and HEADQUARTERS Royal Naval Patrol Service Association Naval Museum, Sparrows Nest, Lowestoft, Suffolk NR32 1XG Charity No. 273148 Tel: 01502 586250 E-mail: [email protected] Shipmates, it is my sad duty to inform you that our National Chairman, John Street, crossed the bar on 25th February. John Robert Street 26/10/1923 – 25/02/2017 John, in recent years, had suffered some health problems, some of which were quite serious but he never let these get in his way. He maintained his three mornings a week at the museum office and continued to represent the Association at events and functions both locally and further afield. His memory was still as good as ever and he continued his effective hold on the association’s reins in his quiet, methodical way, in fact he was at the museum the day before he died. John will be a hard act to follow. John’s funeral was very well attended by his Police colleagues, past and present Civic representatives, local Sea Cadet officers, ex-service associations and Patrol Service members and supporters from both near and far. 6 standards, led by our National Standard, gave John the send off he deserved. The service was conducted by the Vicar of St Margarets and our Padre, Rev Peter Paine. After the service John was buried alongside his wife in Kirkley Cemetery. The following is the eulogy delivered at John’s funeral by our President Cdr. Garry Titmus. John Street It is no coincidence that there is a strong nautical presence to our gathering today, nor is there any surprise to the references to service, devotion and duty as we share our memories of a true gentleman and a dear friend - John Street.