The Saltford Brass Mill Project – a Decade of Industrial Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bath & North East Somerset Council

Bath & North East Somerset Council MEETING: Development Control Committee AGENDA 3rd September 2014 ITEM MEETING NUMBER DATE: RESPONSIBLE Lisa Bartlett, Development Manager of Planning and OFFICER: Transport Development (Telephone: 01225 477281) TITLE: LIST OF APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATE AUTHORITY FOR THE PERIOD - 18 th July 2014 to 12 th August 2014 DELEGATED DECISIONS IN RESPECT OF PLANNING ENFORCEMENT CASES ISSUED FOR PERIOD WARD: ALL BACKGROUND PAPERS: None AN OPEN PUBLIC ITEM INDEX Applications determined by the Development Manager of Planning and Transport Development Applications referred to the Chair Delegated decisions in respect of Planning Enforcement Cases APPLICATIONS DETERMINED BY THE DEVELOPMENT MANAGER OF PLANNING AND TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT App. Ref . 14/01073/LBA Type: Listed Building Consent (Alts/exts) Location: 9 Duke Street City Centre Bath Bath And North East Somerset BA2 4AG Ward: Abbey Parish: N/A Proposal: Internal works to facilitate partition wall (regularisation). Applicant: Mr Michael Fortune Decision Date: 25 July 2014 Expiry Date: 22 July 2014 Decision: REFUSE Details of the decision can be found on the Planning Services pages of the Council’s website by clicking on the link below: http://idox.bathnes.gov.uk/WAM/showCaseFile.do?appNumber=14/01073/LBA App. Ref . 14/01316/LBA Type: Listed Building Consent (Alts/exts) Location: New Church 10 Henry Street City Centre Bath Bath And North East Somerset Ward: Abbey Parish: N/A Proposal: External alterations for the provision of 2 flues Applicant: Deloitte LLP Decision Date: 4 August 2014 Expiry Date: 11 August 2014 Decision: CONSENT Details of the decision can be found on the Planning Services pages of the Council’s website by clicking on the link below: http://idox.bathnes.gov.uk/WAM/showCaseFile.do?appNumber=14/01316/LBA App. -

Waterway Dimensions

Generated by waterscape.com Dimension Data The data published in this documentis British Waterways’ estimate of the dimensions of our waterways based upon local knowledge and expertise. Whilst British Waterways anticipates that this data is reasonably accurate, we cannot guarantee its precision. Therefore, this data should only be used as a helpful guide and you should always use your own judgement taking into account local circumstances at any particular time. Aire & Calder Navigation Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Bulholme Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 6.3m 2.74m - - 20.67ft 8.99ft - Castleford Lock is limiting due to the curvature of the lock chamber. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Castleford Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom 61m - - - 200.13ft - - - Heck Road Bridge is now lower than Stubbs Bridge (investigations underway), which was previously limiting. A height of 3.6m at Heck should be seen as maximum at the crown during normal water level. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Heck Road Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.71m - - - 12.17ft - 1 - Generated by waterscape.com Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Leeds Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.5m 2.68m - - 18.04ft 8.79ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Crown Point Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.62m - - - 11.88ft Crown Point Bridge at summer levels Wakefield Branch - Broadreach Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.55m 2.7m - - 18.21ft 8.86ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. -

Bridge Over the River Avon Being Considered Once More

THE WEEK IN East Bristol & North East Somerset FREE Issue 644 9th September 2020 Read by more than 40,000 people each week Bridge over the River Avon being considered once more Wessex Water is once needs to be upgraded in faces is how to get works without the need to travel Council had screened the to Saltford Parish Council to again exploring the order to both improve the traffic to and from the site. through Saltford village, as proposals from an advise that it had exhausted prospect of a bridge across quality of water and handle The company engaged well as open up leisure environmental point of view all the alternative options the River Avon from the increased demand from consultants to evaluate the access for pedestrians and and said there would be no and was considering the Swineford to Saltford. new housing schemes in prospect of a 25ft high cyclists. Last August (Issue significant impacts. bridge option once more. The water recycling centre Bath and the local area. But bridge across the river which 589) we reported that Bath While the prospect of a Continued on page 2 at Mead Lane in Saltford the problem Wessex Water could serve Mead Lane & North East Somerset pedestrian crossing was welcomed, there were major concerns in the Bitton and Swineford area over the increase in traffic and the junction with the A431 which would have been necessary. Wessex Water ultimately decided not to pursue the The plan produced by Atkins last year project but last week wrote Also in this EE apologises for lost Deadlock over Keynsham students left Popular Oldland pub mobile phone service Brislington housing plan stranded without bus on the market week’s issue . -

Bristol Harbour Information for Boaters

covers_308330.qxd 9/7/18 14:13 Page 3 RST L Information for boaters covers_308330.qxd 9/7/18 14:13 Page 4 SAFE HAVENS IN THE BRISTOL CHANNEL PORTISHEAD QUAYS MARINA & PENARTH QUAYS MARINAS PORTISHEAD Tel: 01275 841941 PENARTH Tel: 02920 705021 ■ Professional, friendly staff on duty 24 hrs ■ Professional, friendly staff on duty 24 hrs ■ Excellent access average HW +/- 4 hours ■ Fully serviced berths within Cardiff Bay ■ Fully serviced berths ■ Controlled access and car parking ■ Full boatyard facilities with lifting up to ■ Full boatyard facilities with lifting up to 35 tonnes 20 tonnes ■ Diesel & Petrol available ■ Diesel & Petrol available ■ Chandlery & workshop facilities ■ Chandlery & workshop facilities ■ Excellent road access - 5 mins from ■ Excellent road access 10 mins from junction 19 - M5plus junction 13 - M4 QUAY offering real ‘added value’ for our customers FREE periods of hard standing for annual berth holders* FREE reciprocal berthing between all Quay Marinas for all annual berth holders 50% discounted visitor berthing at 70 TransEurope marinas for berth holders 50% upto 50% off standard tariff for winter berthing 20% 20% off standard insurance rates through Quay Marinas scheme with Towergate Insurance. 15% 15% first year berth discount for boats sold into our marinas by our on-site brokers. * not applicable to Bangor Marina www.quaymarinas.com editorial_308330.qxd 9/7/18 10:47 Page 1 Marine engineering, Servicing, General boat maintenance, Engine sales and installs, Marine salvage Undercover boat storage, craning facilities -

Saltford Walk 5 – Village Footpaths, Brass Mill and the Shallows

Saltford Walk 5 – Village footpaths, Brass Mill and The Shallows 8 Start 9 1 7 10 6 14 13 12 11 5 4 3 2 A short walk round the hidden footpaths in Saltford Village, taking in the Brass Mill and The Shallows, and with lovely views over the river to Kelston Round Hill. Start point Queen Square Distance: 1.3 miles, circular walk Going: Easy; some steps and short hills Facilities: The Bird In Hand Toilets at The Shallows car park Saltford Walk 5 – Village footpaths, Brass Mill and The Shallows Walk up the High Street and just after Homefield Close turn left into the public footpath by the side of no. 16 (1). Shortly the path reaches the side of the railway cutting. Keep on this path, ignoring side paths to the left and right. This path, formerly known as The Mallows / Mallis, went from this point across the ‘Home Field’ to a stile at the top of Saltford Hill. When the GWR railway was built, the path was diverted to the route you are now following. The Home Field has been described as ‘the playground of Saltford in olden days’.1 As you look over the railway cutting towards the Kingfisher Lodge Care Centre, you get a good impression of just how much rock and soil must have been removed when the cutting and tunnel were dug – all by hand of course - back in 1836. Just past the bridge over the railway (that leads to the A4 at the top of Saltford Hill) (2), turn sharp left, over the stone stile, and down the steps to the road at the bottom. -

The Bristol Brass Industry: Furnace Structures and Their Associated Remains Joan M Day

The Bristol brass industry: Furnace structures and their associated remains Joan M Day Remains of the once-extensive Bristol brass industry failed appear to have been complex. Political and can still be seen at several sites on the banks of the economic developments of the time contributed to A von and its tri butaries between Bath and Bristol.! varying extents. So too, did the availability of raw They are relics of the production of brass and its materials and good sources of fuel and waterpower, but manufacture which nourished during the eighteenth technical innovation in the smelting of copper, which century to become the most important industry of its was being evolved locally, provided a major component kind in Europe, superseding continental centres of of the initial success.3 It laid foundations for Bristol's similar production. By the close of the century Bristol domination of the industry throughout the greater part itself was challenged by strong competition and the of the eighteenth century. adoption of new techniques in Birmingham, and thereafter suffered a slow decline. Still using its Significantly, it was Abraham Oarby who was eighteenth-century water-powered methods the Bristol responsible as 'active man', together with Quaker industry just managed to survive into the twentieth partners, for launching the Bristol company in 1702. century, finally closing in the 1920s.2 After some five years' experience in employing coal• fired techniques in the non-ferrous metals industry he The factors which gave impetus to the growth -

SCAN Feb 2003.Pdf

Issue No 48 FEB/MARCH 2003 I ARE YOU INTERESTED IN SAL TFORD I SALTFORD I NEEDS YOU I '" like" being involved in decision making '" have ideas for improving our village '" why not consider being a Parish Councillor '" come to a Council meeting' - 7.45 pm at Salt ford Hall the 1 st Tuesday of every month IN.MAY 2003 WE HAVE ELECTIONS FOR SALTFORD PARISH COUNCIL TO ELECT 11 COUNCILLORS FOR THE NEXT 4 YEARS Meetings are twice monthly in the evening and the duties, though important, are not onerous I 'Y If you are interested contact any Councillor or our Parish Clerk, Peter Godfrey on (01225) 400058 or email [email protected] ~THESE SCEPTRED ISLES" MUSIC FROM ALL PARTS OF THE UNITED KINGDOM A CONCERT BY KEYNSHAM ORCHESTRA CONDUCTOR: ROBERT JENNER AT SALTFORD HALL SATURDAY 8TH FEBRUARY 2003 AT 7.30p.m. Tickets £6.00 and £4.00 concessions (including free drink) :\vailable at the door and in advance from Shelagh's Drapery, Saltford or Members of the Orchestra. (For further details see under Keynsham Orchestra on page 13) PHOTOGRAPHER KEITH JAMES Roger M. Clark Impa Keynsham tel: fax 0117 986 4855 Barber Digital Imaging 37, High Street, Photo-restoration Keynsham Wedding, Portrait and Industrial (entrance by Home Brew Shop) Your pictures on CD or Video See items of interest QUALIFIED elsewhere in this issue AROMATHERAPIST & +++++t+ REFLEXOLOGIST Keynsham Orchestra" Concert M.I.C.H.T. Sat 8th Feb - Pages 1 & 1 9 +++++++ CHRISTINE DIMERY Saltford Golf Club Coffee I.I.H.H.T. Morning Thurs 6th March - Page13 Dips:- Aromatherapy, Massage, +++++++ Anatomy, & Physiology St Mary's Church Coffee C&G in Counselling Morning Reflexology Mon 24th March - Page13 +++++++ Home Tel: 01225 872105 St Mary's Church Book Sale Mobile: 07790 357155 Sat 1st March - Page 13 GIFT VOUCHERS AVAILABLE The Weighbridge Newton St. -

West of England Strategic Economic Plan 2015-2030 01 Contents

WE ARE A PARTNERSHIP FOR GROWTH EMBRACING GROWTH DEAL NEGOTIATIONS FOR 2015-2021 WEST OF ENGLAND STRATEGIC ECONOMIC PLAN 2015-2030 01 CONTENTS Curriculum Vitae: Knowledge, Innovation, Quality of Life 03 Forewords by James Dyson and Colin Skellett 04 1 The West of England Strategic Economic Plan 06 2 The City Region of Choice for a sustainable future 18 3 Economic Strategy 24 4 Local Growth Fund Deal Negotiations 31 5 Using our Levers of Growth 62 5.1 People – Knowledge Economy, Skills & Social Inclusion 63 5.2 Place & Infrastructure 70 5.3 Investment & Promotion 78 5.4 SME Business Support 82 6 Implementation Plan 88 7 Delivery Plan 96 8 Evaluation Plan 106 Appendices 112 Appendix 1: Six Year Plan for the Local Growth Fund 114 Appendix 2: FE Capital Projects – a breakdown of individual proposals 116 Appendix 3: Deadweight and displacement calculations 118 Appendix 4: Pipeline of interventions for the Local Growth Fund 120 3-6 year programme Appendix 5: The Process to identify Interventions for the 124 Local Growth Fund Appendix 6: Shared Priority Investment Maps & Key 126 Appendix 7: Full Business Case Template 138 Technical Supporting Documents available on the LEP website: www.westofenglandlep.co.uk/strategicplan 1 Outline Business Cases for the Local Growth Fund current 2 year programme 2 LEP Sector Prospectus 3 Equality Impact Assessment CuRRICULUM VITAE: KNOWLEDGE, INNOVATION, QUALITY OF LIFE 02|03 CuRRICULUM VITAE KNOWLEDGE, INNOVATION, QUALITY OF LIFE • Over one million people and growing Knowledge Quality of Life • An economy worth -

Newbridge House Brochure

NEWBRIDGE HOUSE BATH • BA1 NEWBRIDGE HOUSE BATH • BA1 An outstanding Grade II listed Regency house with panoramic views Entrance Hall • Drawing Room • Withdrawing Room Games Room • Cinema • 2 Home Offices Kitchen • Dining Room • Utility Room Gym • Bathroom • 3 Cloakrooms • Vault Master Bedroom Suite • 6 Double Bedrooms 5 En Suite Bath/Shower Rooms • Study • Roof Terrace Self Contained Apartment Kitchen • Living Room • Double Bedroom • Shower Room Gardens approximately 1.39 acres Double Garage • Outbuilding • Parking for Several Cars 2.5 miles from City Centre and Bath Spa Railway Station ﴿London Paddington 90 minutes﴾ ﴿miles from M4 ﴾J18 10 ﴿All distances are approximate﴾ These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation Newbridge House is situated between the village of Kelston and the city of Bath. The village of Kelston lies to the west and is close to the River Avon, lying within a Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Chelsea Road is just a few minutes away and provides many local amenities including a cafe, a hairdressers, a bakery, a deli, a greengrocer, a hardware shop, a Spar supermarket and a cycle shop. There is also a post office on Newbridge Road. Weston Village is close by and an offers additional selection of local amenities including a bakery, a Tesco supermarket, pet shop, pharmacy, two takeaways, two newsagents, a greengrocer and a hair salon. The city of Bath is a cultural hub in the region with its world‐famous Roman Baths. -

Saltford Brass Mill Project

SALTFORD BRASS MILL PROJECT Trustees Annual Report 01 2017 This report covers the 2017 operating period and preparations for 2018 Aim 1. This is the first annual report of the trustees of the Saltford Brass Mill Project. The project group was formed in 1997 to maintain the mill, interpret the history of the brass industry and open the mill to the public. Since its formation, the project has operated as an unincorporated organisation. 2. As reported in 2017, the project intended to register as a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (CIO). One advantage of being a CIO would enable SBMP to enter into a more formal agreement with B&NES for the pursuance of the aims of the project, B&NES only being able to enter into an agreement with a legally recognised organisation. 3. The Saltford Brass Mill Project was entered onto the Register of Charities with the Registered Charity Number 1174901 on 27th September 2017. A draft agreement between the SBMP and B&NES has been produced and is under consideration with B&NES legal department and executive committee. Charitable Purpose 4. The Charitable Purpose of the Saltford Brass Mill Project are: a. The preservation and maintenance of the Saltford Brass Mill, on the river Avon in Somerset, for the public benefit. b. To advance the education of the public in the subject of the Mill. c. For the public benefit to advance education in the history of the brass industry in North East Somerset and the Bristol region by facilitating and supporting research into the industry, its working method and people involved. -

WADIHS Weekend 2013 North Somerset

WADIHS Weekend 2013 North Somerset Friday 20th – Sunday 22nd September 2013 Provisional Programme This far ahead final arrangements, because of winter shutdowns and maintenance programmes, have yet to be agreed with all locations but it looks like it will be as follows. We have visited all the locations. Please visit the Websites for an excellent overview of the treats in store. Maps: OS Explorer 142 and 155. 3 for 2 at Waterstones at the moment. Friday afternoon Radstock Museum. www.radstockmuseum.co.uk Comprehensive displays on extraction and processing industries. Introductory talk/s on North Somerset Industrial History including coal-mining, stone extraction, canal and railway building from either Museum staff or a member of Bath & Camerton Archaeological Society. If time permits and subject to availability, visit the Somerset & Dorset Railway Heritage Trust in Midsomer Norton. www.sdjr.co.uk Saturday Somerset Coal Canal www.coalcanal.org Guided walk by a member of the Somerset Coal Canal Society of some of the recently revealed 22 stair-case lock system enabling coal transport from Radstock and Paulton to the Kennet & Avon Canal. Various books available on SCC on line print on demand. See Abebooks for range of offers. Lunch at the canal café at Limpley Stoke and a walk to see the Dundas Aqueduct and junction of the SCC with the K & A. Saltford Brass mill Project www.brassmill.com On the River Avon between Bath & Bristol. Visit & guided talk on this survivor of the region’s former extensive Brass industry. Joan Day (1973) Bristol Brass A History of the Industry. -

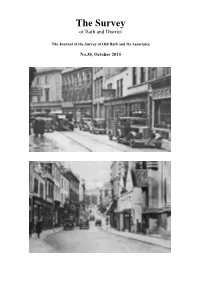

The Survey of Bath and District

The Survey of Bath and District The Journal of the Survey of Old Bath and Its Associates No.30, October 2015 The Survey of Bath and District No.30, 2015 THE SURVEY OF BATH AND DISTRICT The Journal of the Survey of Old Bath and its Associates Number 30 October 2015 CONTENTS City News: Bath Record Office Reports from Local Societies: Survey of Old Bath Friends of the Survey History of Bath Research Group Widcombe and Lyncombe Local History Society South Stoke History Committee The Freshford & District Local History Society Notes and Queries: The Diaries of Fanny Chapman A Bit more on the James Street West Labour Exchange Portway House, Weston Archaeology/Publications Articles: The Bladud Spa John Macdonald The Johnson Family of South Stoke, a Remarkable Parsonage Family Robert Parfitt The History of Broad Street - A Study of the Sites: Part I, The West Side Elizabeth Holland and Margaret Burrows Friends of the Survey: List of Members Editor: Mike Chapman, 51 Newton Road, Bath BA2 1RW tel: 01225 426948, email: [email protected] Layout and Graphics: Mike Chapman Printed by A2B Print Solutions, Pensford Front Cover Illustration: Lower Broad Street in the 1930s, looking South. Back Cover Illustration: Lower Broad Street in the 1940s, looking North. 1 The Survey of Bath and District No.30, 2015 CITY NEWS Bath Record Office We have made major progress this year on cataloguing the huge quantity of Council records held in the Record Office. This has been made possible by a significant grant in 2014 from the National Cataloguing Grant Programme for archives, and another in 2015 from the Heritage Lottery Fund.