Open Brian Macauley Dissertation Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

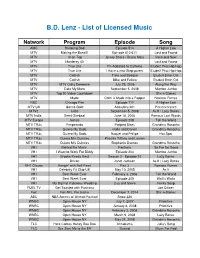

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

Marine Assigned to 2Nd Battalion, 3Rd Marine Regiment's Scout Sniper Platoon Focuses in on a Target at Range 400, Twentynine Palms, Admiral William J

Hawaii ARINEARINE MVMOLUME 36, NUMBER 27 2005 THOMAS JEFFERSON AWARD WINNING METRO FORMAT NEWSPAPER JULY 14, 2006 RIMPAC Metal Body Search A-3 B-1 C-1 Word of thanks Lance Cpl. Luke Blom Tony Blazejack A Marine assigned to 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment's Scout Sniper Platoon focuses in on a target at Range 400, Twentynine Palms, Admiral William J. Fallon, commander, United States Pacific Calif. Marines assigned to Hawaii-based 2/3 are in California where they are undergoing training for their upcoming deployment to Iraq. Command, addresses Marines from 1st Battalion, 3rd Regiment at the Base Chapel July 7. Adm. Fallon was aboard base to thank 1/3 "Lava Dogs" for their recent efforts in Afghanistan and to further coordinate with the unit's leaders. Snipers: Eye in the sky 3/3 keeps Iraq’s Lance Cpl. Luke Blom “Everyone thinks our job is just company-level assault range here, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment shooting, but I would say that close July 8. to 90 percent of our job is done Range 400 is an assault course waterways safe MARINE CORPS AIR GROUND without pulling the trigger,” said where Marines clear simulated COMBAT CENTER TWENTYNINE Cpl. Benjamin Pratt, Scout Sniper enemy positions from more than two Sgt. Roe F. Seigle PALMS, Calif. — The Marine scout Platoon, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine kilometers of desert terrain. While 1st Marine Division sniper is known to be a marksman Regiment team leader. “Most of the the rifle platoons rush the objec- who moves through a battlefield like time we’re doing surveillance, recon- tives, they’re given supporting fire HADITHA, Iraq — In Iraq, a country where temper- a ghost, taking shots from impossi- naissance, controlling indirect fire by 81mm mortars, 60mm mortars, atures often soar above 110 degrees and terrain is most- ble distances and hitting his mark or CAS (Close Air Support).” and a squad of heavy machine guns, ly fine grains of sand, Cpl. -

DOES REALITY TV INDUCE REAL EFFECTS? on the QUESTIONABLE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN 16 and PREGNANT and TEENAGE CHILDBEARING David A

DOES REALITY TV INDUCE REAL EFFECTS? ON THE QUESTIONABLE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN 16 AND PREGNANT AND TEENAGE CHILDBEARING David A. Jaeger Theodore J. Joyce Robert Kaestner November 2016 Acknowledgements: The authors thank Phil Levine for his generous assistance in replicating results, and Bill Evans, Gary Solon, and seminar participants at Columbia University, the CUNY Graduate Center, the CUNY Institute for Demographic Research, the Guttmacher Institute, Princeton University, and the University of Michigan for helpful comments. Onur Altindag provided exemplary research assistance. Joyce and Kaestner acknowledge support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R01 HD082133 and from the Health Economics Program of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Nielsen ratings data are proprietary and cannot be shared. Birth data from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) have confidential elements and must be obtained directly from NCHS. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2016 by David A. Jaeger, Theodore J. Joyce, and Robert Kaestner. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Does Reality TV Induce Real Effects? On The Questionable Association between 16 And Pregnant and Teenage Childbearing November 2016 JEL No. J13, L82 ABSTRACT We reassess evidence that the MTV program 16 and Pregnant played a major role in reducing teen birth rates in the U.S. (Kearney and Levine, American Economic Review 2015). We find Kearney and Levine’s identification strategy to be problematic. Through a series of placebo and other tests, we show that the assumptions necessary for a causal interpretation of their results are not met. -

MICHIGAN MONTHLY ______January/Feb

MICHIGAN MONTHLY ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ January/Feb. 2020 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ DETROIT RED WINGS – LITTLE CAESARS DETROIT PISTONS – LITTLE CAESAR’S ARENA ARENA – on FSD unless otherwise stated Jan. 2 at L.A. Clippers; 10:30 pm Jan. 3 at Dallas Stars; 8:30 pm Jan. 4 at Golden State Warriors; 8:30 pm Jan. 5 at Chicago Blackhawks; 7:30 pm Jan. 5 at L.A. Lakers; 10 pm Jan. 7 vs. Montreal Canadiens; 7:30 pm Jan. 7 at Cleveland Cavaliers; 7 pm Jan. 10 vs. Ottawa Senators; 7:30 pm Jan. 9 vs. Cleveland Cavaliers; 7 pm Jan. 12 vs. Buffalo Sabres; 5 pm Jan. 11 vs. Chicago Bulls; 7 pm Jan. 14 at New York Islanders; 7 pm Jan. 13 vs. New Orleans Pelicans; 7 pm Jan. 17 vs. Pittsburgh Penguins; 7:30 pm Jan. 15 at Boston Celtics; 7 pm Jan. 18 vs. Florida Panthers; 7 pm Jan. 18 at Atlanta Hawks; 7:30 pm Jan. 20 at Colorado Avalanche; 3 pm Jan. 20 at Washington Wizards; 2 pm Jan. 22 at Minnesota Wild; 8 pm Jan. 22 vs. Sacramento Kings; 7 pm Jan. 31 at New York Rangers; 7 pm Jan. 24 vs. Memphis Grizzlies; 7 pm Feb. 1 vs. New York Ranges; 7 pm Jan. 25 vs. Brooklyn Nets; 7 pm Feb. 3 vs. Philadelphia Flyers; 7:30 pm Jan. 27 vs. Cleveland Cavaliers; 7 pm Feb. 6 at Buffalo Sabres; 7 pm Jan. 29 at Brooklyn Nets; 7:30 pm; ESPN Feb. 7 at Columbus Blue Jackets; 7 pm Jan. 31 vs. Toronto Raptors; 7 pm Feb. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Annual Review 2009 Sharks (Costa Rica), Pretoma

Annual Review 2009 Sharks (Costa Rica), Pretoma Contents Page Charity information 3 Report of the Trustees 4 1. About us and our public benefit 4 2. Objectives and activities for public benefit 6 3. Assessing our performance and achievements 11 4. Our plans for the future to continue to deliver benefit to the public 13 5. Financial review 14 6. Structure, governance and management 14 7. Statement of Trustees’ responsibilities 16 Financial overview 18 Statement of financial activities for the year ended 31 March 2009 18 Balance sheet at 31 March 2009 19 From top Green turtles (Sri Lanka), Scarlet macaws (Guatemala), Whale sharks (Costa Rica) Annual Review 2009 www.bbc.co.uk/bbcwildlifefund Charity information Chairman Bernard Mercer Company registration number 6238115 Deputy Chairman Neil Nightingale Registered charity number 1119286 Treasurer Heather Woods née Brindley Registered office British Broadcasting Corporation Trustees Toby Aykroyd 201 Wood Lane Yogesh Chauhan London W12 7TS John Burton (until 23 July 2008) Auditors Mazars LLP Sarah Ridley Times House Shyam Parekh Throwley Way Georgina Domberger Sutton Secretary Melissa Price (until 23 July 2008) Surrey SM1 4QJ Amy Ely Bankers HSBC Project Manager Lydia Thomas (until 3 April 2009) Regional Services Centre Europe PO Box 125 2nd Floor, 62-76 Park Street London SE1 9DZ Solicitors Farrer & Co 66 Lincoln’s Inn Fields London WC2A 3LH Above Elephant water hole, Kipsing, Kenya Annual Review 2009 www.bbc.co.uk/bbcwildlifefund About us and our public benefit Our objects What we do The BBC Wildlife Fund was set up in 2007 by the BBC to help pro- The BBC Wildlife Fund is a charitable organisation that raises funds tect endangered species around the world and in the UK, identifying from the public to help conserve and protect endangered species not only the most endangered animals on the planet but also those and the habitats on which they depend. -

Docuseries Flat Out, Produced by Vuguru the Non-fi Ction Camp

MAY / JUNE 13 THE REALITY REPORT Syfy’s Haunted Highway and adventures in the US $7.95$7.95 USD New Paranormal CanadaCanada $$8.958.95 CDN Int’lInt’l $$9.959.95 USD G<ID@KEF%+*-* 9L==8CF#EP L%J%GFJK8><G8@; 8LKF ALSO: UNSCRIPTED GOES ONLINE | U.S. CABLE SLATES REVEALED GIJIKJK; A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. RRealscreenealscreen Cover.inddCover.indd 1 116/05/136/05/13 22:16:16 PPMM Congratulations Bertram We are proud to call you family. CBS is proud to support the Realscreen Awards. ©2013 CBS Corporation RRS.23322.CBS.inddS.23322.CBS.indd 1 113-05-163-05-16 22:01:01 PPMM contents may / june 13 Sundance Grand Jury and Audience Award winner 35 42 Blood Brother is part of our annual Festival Report. BIZ Unscripted action at the NewFronts; Dubuc and Raven upped at A+E ......................................................... 9 Super 8 fi lm shot by Nixon’s top aides is featured in Our Nixon (Still courtesy of Dipper Films). IDEAS & EXECUTION U.S. cable nets unveil slates; crowdfunding words of wisdom ...........13 “The perception was you SPECIAL REPORTS could pitch a show on a THE REALITY REPORT A look into the Emmy Reality Peer Group; log line, put 10 cameras paranormal reality revamps .............................................................. 27 somewhere, and that STOCK FOOTAGE/ARCHIVE was reality.” 29 Super 8 rules in Our Nixon; 1895 Films’ 9-11: The Heartland Tapes; FOCAL Awards winners and UK copyright news ...............................35 FESTIVAL REPORT 19 Profi les of Gideon’s Army and Blood Brother .......................................40 PRODUCTION MUSIC Music shop execs reveal the dollars and sense behind scoring for shows .................................................45 THINK ABOUT IT Science Channel’s slate features a move into scripted Making talent agreements agreeable ...............................................48 drama, with 73 Seconds: The Challenger Investigation. -

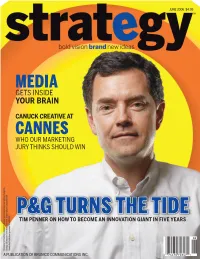

P&G Turns the Tide

MEDIA GETS INSIDE YOUR BRAIN CANUCK CREATIVE AT CANNES WHO OUR MARKETING JURY THINKS SHOULD WIN PP&G&G TTURNSURNS TTHEHE TTIDEIDE TIM PENNER ON HOW TO BECOME AN INNOVATION GIANT IN FIVE YEARS CCover.Jun06.inddover.Jun06.indd 1 55/18/06/18/06 112:13:102:13:10 PPMM SST.6637.TaylorGeorge.dps.inddT.6637.TaylorGeorge.dps.indd 2 55/18/06/18/06 44:23:10:23:10 PMPM taylor george SERVICES OFFERED: Taylor George began operations in the fall of 1995 as a General Agency/AOR two-person design studio. Over the next several years the company grew to a full service agency with a staff of Direct Agency 20. In 2003, Taylor George co founded BRAVE Strategy, Interactive Agency a creative and strategic boutique with expertise in tar- Public Relations Agency geting Canada's diverse Aboriginal population. Design Agency Taylor George and BRAVE are headquartered in Winnipeg, Media Agency Manitoba. The agencies have a sales office in Toronto and will be opening a Vancouver office in July of 2006. “Our approach is all about stories. Stories affect people. APTN Program Guide. Recent national campaigns for Stories APTN have substantially increased audience numbers create emotion. Stories get a response.” Peter George TelPay B-to-B magazine campaign. TelPay President has achieved significant growth since being rebranded by TG in 2005. Subscription Brochure, Manitoba Opera. Season campaign for Manitoba Opera increased subscriptions 28% over the previous year. CLIENT LIST KEY PERSONNEL CONTACT US. 1. Aboriginal People's 12. TelPay Peter George, President and CEO, Taylor George/BRAVE Strategy Television Network 13. -

Monday, June 03, 2013 a Three Day Weekend That Extends Into Monday

Monday, June 03, 2013 A three day weekend that extends into Monday makes for a short week. The short week, in turn, makes for an abundant amount of fast paced activities. Somehow, everyone managed to fit these activities into the four day week. Tuesday evening provided a special time for the school board and I to discuss the district’s vision and goals. The school board’s focused work over the course of the evening provided clear direction for our administration and we look forward to embracing the challenges that lie ahead. Wednesday gave me the chance to walk through my old elementary – Garfield. Although the campus is not the same, walking through some classrooms reminded me of the excitement for learning which teachers created then and continue to create today. When I entered Mrs. Jackeline Rodriguez’s second grade class I observed students working on what appeared to be a writing assignment. As soon as I asked one student for permission to read their essay, four others pleasantly asked me if I would read their work as well. One student suggested that I read all five pieces and then select the best one. Clearly, he suggested we have an essay contest. Being an avid proponent for competition, I agreed and read all five pieces. Congratulations to David Underwood, the winner of our unofficial essay contest. Thursday morning I visited Buena Vista’s Fitness Day and was able to observe firsthand the organized excitement created for the students. Back in our elementary days, the field day events were mostly individual events where there were clearly winners and losers, a notion that is sometimes too hard for a seven year old to handle. -

President's Message

July/Aug 2021 Vol 56-4 63 Years of Dedicated Service to L.A. Your Pension and Health Care Watchdog County Retirees www.relac.org • e-mail: [email protected] • (800) 537-3522 RELAC Joins National Group to Lobby President’s Against Unfair Social Security Reductions Message RELAC has joined the national Alliance for Public Retirees by Brian Berger to support passage of H.R. 2337, proposed legislation to reform the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) of the Social The recovery appears to be on a real path Security Act. to becoming a chapter of our history with whatever sadness or tragedy of which The Alliance for Public Retirees was created nearly a decade we might each have witnessed or been ago by the Retired State, County and Municipal Employees a part. The next few months will be critical as we continue to Association of Massachusetts (Mass Retirees) and the Texas see a further lessening or elimination of restrictions. I don't Retired Teachers Association to resolve the issues of WEP know how I'll ever be able to leave the house or see friends and the Government Pension Offset (GPO). without a mask, at least in the car or in my pocket. In all this Together with retiree organizations, public employee unions past period, however, work has not lessened at RELAC and the and civic associations across the country, the organization programs have continued with positive gains. For that I thank has worked to advance federal legislation through Congress the support staff, each Board member, and the many of you aimed at reforming both the WEP and GPO laws. -

NAME E-Book 2012

THE HISTORY OF THE NAME National Association of Medical Examiners Past Presidents History eBook 2012 EDITION Published by the Past Presidents Committee on the Occasion of the 46th Annual Meeting at Baltimore, Maryland Preface to the 2012 NAME History eBook The Past Presidents Committee has been continuing its effort of compiling the NAME history for the occasion of the 2016 NAME Meeting’s 50th Golden Anniversa- ry Meeting. The Committee began collecting historical materials and now solicits the histories of individual NAME Members in the format of a guided autobiography, i.e. memoir. Seventeen past presidents have already contributed their memoirs, which were publish in a eBook in 2011. We continued the same guided autobiography format for compiling historical ma- terial, and now have additional memoirs to add also. This year, the book will be combined with the 2011 material, and some previous chapters have been updated. The project is now extended to all the NAME members, who wish to contribute their memoirs. The standard procedure is also to submit your portrait with your historical/ memoir material. Some of the memoirs are very short, and contains a minimum information, however the editorial team decided to include it in the 2012 edition, since it can be updated at any time. The 2012 edition Section I – Memoir Series Section II - ME History Series – individual medical examiner or state wide system history Presented in an alphabetic order of the name state Section III – Dedication Series - NAME member written material dedicating anoth- er member’s contributions and pioneer work, or newspaper articles on or dedicated to a NAME member Plan for 2013 edition The Committee is planning to solicit material for the chapters dedicated to specifi- cally designated subjects, such as Women in the NAME, Standard, Inspection and Accreditation Program. -

Scarlett Johansson

Cover_July 6/12/06 1:47 PM Page 1 3/C B G R july 2006 | volume 7 | number 7 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40708019 PLUS REESE WITHERSPOON, JIM CARREY AND OTHER STARS GET ALL PHILOSOPHICAL Advertisement Hit TV Lovers Tune to TVtropolis Canada’s New Destination for TV Lovers Perhaps it first hit when you discovered your TVtropolis has all your favourites, series best friend has a name that rhymes with too young to be “classic” on a schedule that’s a female body part. Or the time you almost too good to be true. (Lucky for you, it planned your parents’ anniversary is true!) Weekdays in TVtropolis you’ll hoping it’d be as romantic as Brenda find TV greats, back-to-back: Seinfeld, Ellen, and Dylan’s graduation. Or that day at Grace Under Fire, Married… With Children, the dog park when you spotted the NewsRadio, Ned and Stacey, Frasier, Jack Russell terrier and fought the Beverly Hills 90210 and The Nanny. urge to have a staredown contest. Want a few more familiar faces? It might as well be spelled out in block letters Weekends in TVtropolis you on a 70-inch plasma screen: you, my friend, are a can explore your favourite TV fan of hit TV! From Seinfeld to Beverly Hills stars in a fresh new light with our 90210 to Frasier, you know and love ‘em all.