Vipava River Basin Adaptation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emerald Cycling Trails

CYCLING GUIDE Austria Italia Slovenia W M W O W .C . A BI RI Emerald KE-ALPEAD Cycling Trails GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE 3 Content Emerald Cycling Trails Circular cycling route Only few cycling destinations provide I. 1 Tolmin–Nova Gorica 4 such a diverse landscape on such a small area. Combined with the turbulent history I. 2 Gorizia–Cividale del Friuli 6 and hospitality of the local population, I. 3 Cividale del Friuli–Tolmin 8 this destination provides ideal conditions for wonderful cycling holidays. Travelling by bicycle gives you a chance to experi- Connecting tours ence different landscapes every day since II. 1 Kolovrat 10 you may start your tour in the very heart II. 2 Dobrovo–Castelmonte 11 of the Julian Alps and end it by the Adriatic Sea. Alpine region with steep mountains, deep valleys and wonderful emerald rivers like the emerald II. 3 Around Kanin 12 beauty Soča (Isonzo), mountain ridges and western slopes which slowly II. 4 Breginjski kot 14 descend into the lowland of the Natisone (Nadiža) Valleys on one side, II. 5 Čepovan valley & Trnovo forest 15 and the numerous plateaus with splendid views or vineyards of Brda, Collio and the Colli Orientali del Friuli region on the other. Cycling tours Familiarization tours are routed across the Slovenian and Italian territory and allow cyclists to III. 1 Tribil Superiore in Natisone valleys 16 try and compare typical Slovenian and Italian dishes and wines in the same day, or to visit wonderful historical cities like Cividale del Friuli which III. 2 Bovec 17 was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list. -

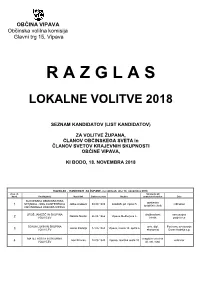

R a Z G L a S

OBČINA VIPAVA Občinska volilna komisija Glavni trg 15, Vipava R A Z G L A S LOKALNE VOLITVE 2018 SEZNAM KANDIDATOV (LIST KANDIDATOV) ZA VOLITVE ŽUPANA, ČLANOV OBČINSKEGA SVETA in ČLANOV SVETOV KRAJEVNIH SKUPNOSTI OBČINE VIPAVA, KI BODO, 18. NOVEMBRA 2018 RAZGLAS - KANDIDATI ZA ŽUPANE, na volitvah, dne 18. novembra 2018 Žreb. št. Strokovni ali kand. Predlagatelj Kandidat Datum rojstva Naslov znanstveni naslov Delo SLOVENSKA DEMOKRATSKA gostinsko STRANKA - SDS, KONFERENCA Jožko Andlovic 30.09.1983 Gradišče pri Vipavi 5 inštruktor 1 turistični tehnik OBČINSKEGA ODBORA VIPAVA UROŠ JANEŽIČ IN SKUPINA družboslovni samostojna Nataša Nardin 26.04.1966 Vipava, Beblerjeva 5 2 VOLIVCEV tehnik podjetnica SONJA LUKIN IN SKUPINA univ. dipl. Poslovno svetovanje Goran Kodelja 17.05.1963 Vipava, Cesta 18. aprila 6 3 VOLIVCEV ekonomist Goran Kodelja s.p. MATEJ HOSTA IN SKUPINA magister veterine Ivan Princes 18.06.1948 Vipava, Goriška cesta 10 veterinar 4 VOLIVCEV dr. vet. med. RAZGLAS – KANDIDATI ZA ČLANE OBČINSKEGA SVETA – volilna enota 1, na volitvah, dne 18. novembra 2018 Z. št. Datum Strokovni ali znanstveni Žreb.št. Ime liste Predlagatelj Kandidat Naslov Delo liste kand rojstva naslov 1 Mitja Lavrenčič 27.06.1960 Vipava, Na Produ 13 dipl. ing. gradbeništva projektant SLS - SLOVENSKA SLS LJUDSKA STRANKA 2 Marija Černigoj 13.10.1953 Vipava, Pod gradom 3 tekstilni tehnik upokojenka 1 OO VIPAVA 3 Boštjan Trošt 01.07.1985 Vipava, Vojkova 42 kemijski tehnik Trgovski poslovodja 1 Damjan Bajec 30.03.1982 Gradišče pri Vipavi 23a u. dip. inž. gosp. vodja projektov 2 Konstanca Tomažič 16.01.1969 Vipava, Beblerjeva ulica 26 dip. upravni organizator administrator 3 Matej Leban 03.01.1980 Gradišče pri Vipavi 22b ek. -

November 2017 Please Open the Document in Adobe Reader Version 9 Or Higher

PILOT CASE STUDY SOČA SLOVENIA NOVEMBER 2017 PLEASE OPEN THE DOCUMENT IN ADOBE READER VERSION 9 OR HIGHER MAIN ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERISTICS THE SOČA BASIN IS COMPOSED OF NUMEROUS HETEROGENEOUS LANDSCAPES WITH VERY DIVERSE CHARACTERISTICS. GORIŠKA BRDA / SOČA PCS / SLOVENIA © ANDREJ BAŠELJ, IzVRS THE SOČA RIVER FLOWS FROM AN ALPINE VALLEY THROUGH DINARIDIC PLATEAU, THE SUB-MEDITERRANEAN AREA AND ENTERS THE ADRIATIC SEA IN THE GULF OF TRIESTE. VIPAVA VALLEY / SOČA PCS / SLOVENIA © MANCA MAGJAR, IzVRS THE SOČA RIVER IS MARKETED AS THE “EMERALD BEAUTY” THANKS TO ITS EMERALD GREEN COLOURED WATER. THE RIVER RETAINS ITS COLOUR THROUGHOUT THE ENTIRE LENGTH. SOČA BASIN / SOČA PCS / SLOVENIA © ANDREJ BAŠELJ, IzVRS THE SOČA RIVER IS A TORRENTIAL RIVER WITH STEEP SLOPES, ROCKY SUBSTRATES AND NUMEROUS MOUNTAIN TRIBUTARIES IN THE UPPER PART. THE LOWER PART IS CHARACTERISED BY STRONG SEDIMENT TRANSPORT AND TERRESTRIAL ALLUVIAL DEPOSITS. UPPER SOČA VALLEY / SOČA PCS / SLOVENIA © SIMONE SOZZI HUMAN ACTIVITIES RELATED TO THE RIVER DUE TO ITS HIGH POTENTIAL FOR HYDROPOWER, LARGE STRUCTURES ARE LOCATED IN THE LOWER PART OF THE SOČA AND SMALLER PLANTS ARE SPREAD ALL OVER THE BASIN. MANY NEW HYDROPOWER PLANTS ARE PLANNED TO BE BUILT. HPP AJBA / SOČA PCS / SLOVENIA © ANDREJ BAŠELJ, IzVRS AQUACULTURE AND RECREATIONAL FISHING ARE TRADITIONAL USES IN THE UPPER PART OF THE PILOT CASE STUDY SOČA. THEY ARE WELL HARMONISED WITH OTHER USES. SOČA RIVER / SOČA PCS / SLOVENIA © MATEVŽ JUS DIVERSE TOURISTIC USES – ESPECIALLY WATER SPORTS AS CANOEING, KAYAKING, RAFTING, BATHING AND CANYONING, HAVE BECOME ECONOMICALLY SIGNIFICANT IN THE LAST DECADES IN THE UPPER SOČA VALLEY. TRNOVO OB SOČI / SOČA PCS / SLOVENIA © ANDREJ BAŠELJ, IzVRS WHILE TRADITIONAL NON-EXTENSIVE USES STILL DEFINE THE LANDSCAPE IN THE UPPER PART OF THE SOČA, INTENSIVE AGRICULTURE IS PRESENT IN VIPAVA VALLEY AND GORIŠKA BRDA, MOSTLY FRUIT AND WINE PRODUCTION. -

Observations of Bora Events Over the Adriatic Sea and Black Sea by Spaceborne Synthetic Aperture Radar

1150 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 137 Observations of Bora Events over the Adriatic Sea and Black Sea by Spaceborne Synthetic Aperture Radar WERNER ALPERS Institute of Oceanography, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany ANDREI IVANOV P.P. Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia JOCHEN HORSTMANN* GKSS Research Center, Geesthacht, Germany (Manuscript received 20 February 2008, in final form 15 September 2008) ABSTRACT Bora events over the Adriatic Sea and Black Sea are investigated by using synthetic aperture radar (SAR) images acquired by the advanced SAR (ASAR) on board the European satellite Envisat.Itisshown that the sea surface roughness patterns associated with bora events, which are captured by SAR, yield information on the finescale structure of the bora wind field that cannot be obtained by other spaceborne instruments. In particular, SAR is capable of resolving 1) bora-induced wind jets and wakes that are organized in bands normal to the coastline, 2) atmospheric gravity waves, and 3) boundaries between the bora wind fields and ambient wind fields. Quantitative information on the sea surface wind field is extracted from the Envisat ASAR images by inferring the wind direction from wind-induced streaks visible on SAR images and by using the C-band wind scatterometer model CMOD_IFR2 to convert normalized cross sections into wind speeds. It is argued that spaceborne SAR images acquired over the east coasts of the Adriatic Sea and the Black Sea are ideal means to validate and improve mesoscale atmospheric models simulating bora events. 1. Introduction co.uk/reports/wind/The-Bora.htm). In Europe, strong bora winds are encountered at 1) the east coast of the Bora winds are regional downslope winds, where cold Adriatic Sea, where they are called Adriatic bora, and 2) air is pushed over a coastal mountain range due to the the east coast of the Black Sea, where they are called presence of a high pressure gradient or by the passage of Novorossiyskaya bora because they are encountered near a cold front over the mountain range. -

LIFE Farming – Environmentally Sustainable Agriculture

LIFE International networking conference LIFE farming – environmentally sustainable agriculture PROGRAMME Tuesday, 8 May 2018 – FIELD TRIP 9.15 Meeting point in front of European Union House, Dunajska cesta 20, Ljubljana 09.30 Departure from Ljubljane Visit of project LIFE ViVaCCAdapt - Adapting to the impacts of climate change in the Vipava Valley (LIFE15 CCA/SI/000070 - ongoing) (KS Ajdovščina, Prešernova 26, 5270 Ajdovščina) The purpose of the project is to establish measures to avoid the adverse effects of 11.00 – 12.30 climate change on agriculture in the area of the Vipava Valley. The project team already prepared a strategy for climate change adaptation. Next steps are establishment of decision support system for irrigation and increasing the surface of green windbreaks. How green windbreaks function, participants will learn on the field, during the visit of project area. 12.30 Departure from Ajdovščina 13.30 – 14.30 Lunch Visit of the Ljubljana Marsh Nature Park and the presentation of LIFE project Intermittent Cerknica Lake (Center Ig, Banija 4, 1292 Ig) LIFE project Intermittent Cerknica Lake (LIFE06 NAT/SI/000069 - finalised) The project aimed to ensure long-term favourable conditions for the conservation of turloughs and other endangered habitat types and associated plant and animal species at Lake Cerknica. It simultaneously sought to promote an even development of local agriculture, forestry, fishing, tourism, recreation and education in accordance with natural values. In overall the project tackled the three main threats identified to the habitats: modified watercourses, abandoning of meadow mowing by local landowners and lack of knowledge of local nature and its conservation. -

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 13 November 2015 English only Economic Commission for Europe Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes Seventh session Budapest, 17–19 November 2015 Item 4(i) of the provisional agenda Draft assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin Assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin* Prepared by the secretariat with the Royal Institute of Technology Summary At its sixth session (Rome, 28–30 November 2012), the Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes requested the Task Force on the Water-Food-Energy-Ecosystems Nexus, in cooperation with the Working Group on Integrated Water Resources Management, to prepare a thematic assessment focusing on the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus for the seventh session of the Meeting of the Parties (see ECE/MP.WAT/37, para. 38 (i)). The present document contains the scoping-level nexus assessment of the Isonzo/Soča River Basin with a focus on the downstream part of the basin. The document is the result of an assessment process carried out according to the methodology described in publication ECE/MP.WAT/46, developed on the basis of a desk study of relevant documentation, an assessment workshop (Gorizia, Italy; 26-27 May 2015), as well as inputs from local experts and officials of Italy. Updates in the process were reported at the meetings of the Task Force. -

2750 € 8 Days 8 Slovenia Food Tours Europe #B1/2405

Full Itinerary and Tour details for Agritourism Foodies 8-day Food Tour in Slovenia Prices starting from. Trip Duration. Max Passengers. 2750 € 8 days 8 Country. Slovenia Experience. Tour Code. Food Tours Europe #B1/2405 Agritourism Foodies 8-day Food Tour in Slovenia Tour Details and Description Imagine: Tasting the authentic and diverse Slovenian cuisine in 5 culinary regions Savoring private winery tours and tastings Eating in a world's best restaurant Seeing the best of different Slovenian regions Learning about the history of the area Cooking traditional dishes with local women Accommodation: Stay in a beautiful family-run tourist farm in Goriška Brda, (Slovenian Tuscany), for a unique cooking and wine tasting holiday. Taste authentic Slovenian food and wine, feel the diverse nature and see the best in different regions with focus on the Mediterranean, (Goriška Brda, Karst, Vipava Valley), and the Julian Alps, (Kobarid). Experiences: When you are not cooking with the local women you will be touring the wonderful countryside, the orchards and vineyards, exploring regional delicacies, enjoying daily tours of local sites and medieval villages, visiting the region's best wineries, eating in a world class restaurant and enjoying breathtaking fairytale landscapes. It’s all about the experience, a combination that allows you to sample both the region’s most refined cuisine and its most rustic traditions. Indulge your passion for food, wine and nature on this fantastic cooking and wine tasting holiday in Slovenia, an experience that you -

HIKING in SLOVENIA Green

HIKING IN SLOVENIA Green. Active. Healthy. www.slovenia.info #ifeelsLOVEnia www.hiking-biking-slovenia.com |1 THE LOVE OF WALKING AT YOUR FINGERTIPS The green heart of Europe is home to active peop- le. Slovenia is a story of love, a love of being active in nature, which is almost second nature to Slovenians. In every large town or village, you can enjoy a view of green hills or Alpine peaks, and almost every Slove- nian loves to put on their hiking boots and yell out a hurrah in the embrace of the mountains. Thenew guidebook will show you the most beauti- ful hiking trails around Slovenia and tips on how to prepare for hiking, what to experience and taste, where to spend the night, and how to treat yourself after a long day of hiking. Save the dates of the biggest hiking celebrations in Slovenia – the Slovenia Hiking Festivals. Indeed, Slovenians walk always and everywhere. We are proud to celebrate 120 years of the Alpine Associati- on of Slovenia, the biggest volunteer organisation in Slovenia, responsible for maintaining mountain trails. Themountaineering culture and excitement about the beauty of Slovenia’s nature connects all generations, all Slovenian tourist farms and wine cellars. Experience this joy and connection between people in motion. This is the beginning of themighty Alpine mountain chain, where the mysterious Dinaric Alps reach their heights, and where karst caves dominate the subterranean world. There arerolling, wine-pro- ducing hills wherever you look, the Pannonian Plain spreads out like a carpet, and one can always sense the aroma of the salty Adriatic Sea. -

A Guide to the Slovene Ethnographic Museum Permanent Exhibition a Guide to the Slovene Ethnographic Museum Permanent Exhibition Contents

A Guide to the Slovene Ethnographic Museum Permanent Exhibition A Guide to the Slovene Ethnographic Museum Permanent Exhibition Contents Title: Slovene Ethnographic Museum on the Map of World Museums 7 I, We, and Others: Images of My World Tanja Roženbergar A Guide to the Slovene Ethnographic Museum Permanent Exhibition Published by: Between Starting Points, Structure, Message, and Incentive 9 Slovene Ethnographic Museum, represented by Tanja Roženbergar Janja Žagar Authors: Andrej Dular, Marko Frelih, Daša Koprivec, Tanja Roženbergar, Polona Sketelj, Exhibition Chapters 31 Inja Smerdel, Nadja Valentinčič Furlan, Tjaša Zidarič, Janja Žagar, Nena Židov In Lieu of Introduction – A Welcome Area for Our Visitors 32 Janja Žagar Editor: Janja Žagar I – The Individual 35 Editorial Board: Janja Žagar Andrej Dular, Polona Sketelj, Nena Židov Translation: My Family – My Home 51 Nives Sulič Dular Polona Sketelj Design: My Community – My Birthplace 65 Eda Pavletič Nena Židov Printed by: Tiskarna Januš Beyond My Birthplace – My Departures 77 Ljubljana, 2019 Inja Smerdel Print Run: 1.000 My Nation – My Country 89 Andrej Dular The publication of this book was made possible by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia My Otherness and Foreign Otherness – The Wide World 103 Marko Frelih, Daša Koprivec, Tjaša Zidarič Me – My Personal World 121 Janja Žagar Exhibition Narrative Translated into Objects 137 Cohesive Threats of the Exhibition 167 An Individual’s Journey 168 Janja Žagar, Andrej Dular Vesna: A Mosaic Video Portrait 175 Nadja Valentinčič Furlan Reflections of Visitors 181 My Life, My World 182 Janja Žagar CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Univerzitetna knjižnica Maribor Gallery of Portraits and Gallery of Narrators 185 39(=163.6)(083.824) Nadja Valentinčič Furlan 069(497.4Ljubljana)SEM:39 Authors 189 SLOVENSKI etnografski muzej I, We, and others : images of my World : a guide to the Slovene Ethnographic Museum permanent exhibition / [authors Andrej Dular .. -

Diapositiva 1

INCENDI BOSCHIVI NEL FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA Nuovi strumenti di conoscenza, prevenzione e previsione VILLA MANIN DI PASSARIANO – 24 Maggio 2012 L’esercitazione internazionale antincendio boschivo “KARST EXERCISE 2011” Piero Giacomelli Gruppo Comunale Volontari Antincendio Boschivo e Protezione Civile TRIESTE esercitazione internazionale antincendio boschivo “KARST EXERCISE 2011” TRIESTE – Domenica 29 Maggio 2011 Obiettivi dell’esercitazione • Verifica delle procedure previste dal Protocollo di cooperazione transfrontaliera tra la Protezione civile della Repubblica di Slovenia e la Protezione civile del Friuli Venezia Giulia del 18 gennaio 2006 • Verifica delle procedure e comunicazioni tra le componenti del Volontariato AIB, del Corpo Forestale, dei Vigili del Fuoco e tra queste e la Sala Operativa Regionale (con particolare riguardo alla nuova rete radio regionale del volontariato) nonché tra le componenti Italiane e Slovene. • Verifica, in ambito carsico, del sistema di monitoraggio degli incendi boschivi tramite Wescam installata su elicottero del Servizio Aereo Regionale. • Verifica del livello di coordinamento tra i responsabili delle operazioni dei vari enti competenti sul territorio. INQUADRAMENTO GENERALE SCENARIO 1 FERNETTI – Bosco LANZI SCENARIO 1 • Si ipotizza che l’incendio sia generato dal passaggio di un convoglio ferroviario lungo la linea Villa Opicina – Sesana. • Nella primissima fase, l’incendio (Incendio 1a) si sviluppa nella zona compresa tra la ferrovia e il confine di Stato, favorito dalla pendenza del terreno e dalla sua conformazione che lo pone al riparo dal vento di bora. Successivamente a causa del vento, alcuni tizzoni oltrepassano la linea ferroviaria innescando la seconda parte dell’incendio che si propaga con rapidità favorito, questa volta, dal vento. • La zona interessata dall’incendio 1a è particolarmente carente di viabilità forestale. -

Jemec Auflič Et Al Landslides 2017B

ICL/IPL Activities Landslides (2017) 14:1537–1546 Mateja Jemec Auflič I Jernej Jež I Tomislav Popit I Adrijan Košir I Matej Maček I Janko Logar I DOI 10.1007/s10346-017-0848-1 Ana Petkovšek I Matjaž Mikoš I Chiara Calligaris I Chiara Boccali I Luca Zini I Jürgen M. Reitner I Received: 14 February 2017 Timotej Verbovšek Accepted: 22 May 2017 Published online: 23 June 2017 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany 2017 The variety of landslide forms in Slovenia and its immediate NW surroundings Abstract The Post-Forum Study Tour following the 4th World Adriatic plate and being squeezed between the African plate to the Landslide Forum 2017 in Ljubljana (Slovenia) focuses on the vari- south and the Eurasian plate to the north. The Adriatic plate ety of landslide forms in Slovenia and its immediate NW sur- rotates counter-clockwise, which causes movements particularly roundings, and the best-known examples of devastating on the northern and eastern sides (Gosar et al. 2009). Numerous landslides induced by rainfall or earthquakes. They differ in com- active faults and thrust systems affect the country and define its plexity of the both surrounding area and of the particular geolog- diverse morphology and unfavourable geological conditions. In ical, structural and geotechnical features. Many of the landslides of general, the geological setting of Slovenia is very diverse and the Study Tour are characterized by huge volumes and high veloc- mainly composed of sediments or sedimentary rocks (53.5%), ity at the time of activation or development in the debris flow. In clastic rocks (39.3%), metamorphic (3.9%), pyroclastic (1.8%) and addition, to the damage to buildings, the lives of hundreds of igneous (1.5%) rock outcrop (Komac 2005). -

Portrait of the Regions – Slovenia Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities 2000 – VIII, 80 Pp

PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS 13 17 KS-29-00-779-EN-C PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS VOLUME 9 SLOVENIA VOLUME 9 SLOVENIA Price (excluding VAT) in Luxembourg: ECU 25,00 ISBN 92-828-9403-7 OFFICE FOR OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES EUROPEAN COMMISSION L-2985 Luxembourg ࢞ eurostat Statistical Office of the European Communities PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS VOLUME 9 SLOVENIA EUROPEAN COMMISSION ࢞ I eurostat Statistical Office of the European Communities A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2000 ISBN 92-828-9404-5 © European Communities, 2000 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium II PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS eurostat Foreword The accession discussions already underway with all ten of the Phare countries of Central and Eastern Europe have further boosted the demand for statistical data concerning them. At the same time, a growing appreciation of regional issues has raised interest in regional differences in each of these countries. This volume of the “Portrait of the Regions” series responds to this need and follows on in a tradition which has seen four volumes devoted to the current Member States, a fifth to Hungary, a sixth volume dedicated to the Czech Republic and Poland, a seventh to the Slovak Republic and the most recent volume covering the Baltic States, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Examining the 12 statistical regions of Slovenia, this ninth volume in the series has an almost identical structure to Volume 8, itself very similar to earlier publications.