Monet: the Early Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avis D'enquête Publique

LIBERTÉ ‐ ÉGALITÉ – FRATERNITÉ RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE LIBERTÉ ‐ ÉGALITÉ – FRATERNITÉ PRÉFET DES YVELINES Direction Régionale et Interdépartementale de l'Environnement et de l’Énergie d’Île de-France Unité départementale des Yvelines AVIS D’ENQUÊTE PUBLIQUE Demande d’autorisation de recherche de gîte géothermique basse température dit «Grand Parc Nord », présentée par la société ENGIE ENERGIE SERVICES Par arrêté préfectoral du 12 juin 2020, une enquête publique d’une durée de 22 jours est organisée du 8 juillet 2020 au 29 juillet 2020 inclus sur la demande d’autorisation de recherche de gîte géothermique basse température (inférieure à 150 °C) au Dogger et au Trias, présentée par la société ENGIE ENERGIE SERVICES, pour une durée de 3 ans. Le site de recherche concerne, pour tout ou partie, les communes du Chesnay- Rocquencourt, Versailles, Bailly, Marly-le-Roi, Louveciennes, Bougival et La Celle-Saint- Cloud. Le dossier d’enquête publique comporte notamment les caractéristiques du projet et les informations environnementales. Pendant la durée de l’enquête, le dossier est consultable : - sur internet aux adresses suivantes : • http://demande-autorisation-recherche-gite-geotherm ique-le-chesnay.enquetepublique.net • http://www.yvelines.gouv.fr/Publications/Enquetes-p ubliques/Geothermie (Préfecture des Yvelines), - sur support papier et support informatique, aux mairies du Chesnay-Rocquencourt, La Celle-Saint-Cloud et Louveciennes, aux jours et horaires d’ouverture au public. Le public peut consigner ses observations et propositions directement sur le registre d’enquête à feuillets non mobiles, côté et paraphé par le commissaire-enquêteur, ouvert à cet effet dans les mairies du Chesnay-Rocquencourt, La Celle-Saint-Cloud et Louveciennes pendant la durée de l’enquête. -

From the Lands of Asia

Education Programs 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preparing students in advance p. 4 Vocabulary and pronunciation guide pp. 5–8 About the exhibition p. 9 The following thematic sections include selected objects, discussion questions, and additional resources. I. Costumes and Customs pp. 10–12 II. An Ocean of Porcelain pp. 13–15 III. A Thousand Years of Buddhism pp. 16–19 IV. The Magic of Jade pp. 20–23 Artwork reproductions pp. 24–32 4 PREPARING STUDENTS IN ADVANCE We look forward to welcoming your school group to the Museum. Here are a few suggestions for teachers to help to ensure a successful, productive learning experience at the Museum. LOOK, DISCUSS, CREATE Use this resource to lead classroom discussions and related activities prior to the visit. (Suggested activities may also be used after the visit.) REVIEW MUSEUM GUIDELINES For students: • Touch the works of art only with your eyes, never with your hands. • Walk in the museum—do not run. • Use a quiet voice when sharing your ideas. • No flash photography is permitted in special exhibitions or permanent collection galleries. • Write and draw only with pencils—no pens or markers, please. Additional information for teachers: • Please review the bus parking information provided with your tour confirmation. • Backpacks, umbrellas, or other bulky items are not allowed in the galleries. Free parcel check is available. • Seeing-eye dogs and other service animals assisting people with disabilities are the only animals allowed in the Museum. • Unscheduled lecturing to groups is not permitted. • No food, drinks, or water bottles are allowed in any galleries. -

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 • Fourth Sunday After Pentecost

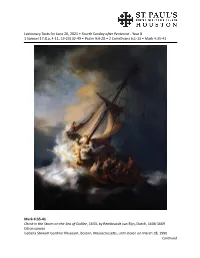

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 •Fourth Sunday after Pentecost- Year B 1 Samuel 17:(1a, 4-11, 19-23) 32-49 • Psalm 9:9-20 • 2 Corinthians 6:1-13 • Mark 4:35-41 Mark 4:35-41 Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633, by Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606-1669 Oil on canvas Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, until stolen on March 18, 1990 Continued Lectionary Texts for the Fourth Sunday after Pentecost• June 20, 2021 • Page 2 In his only painted seascape, Rembrandt dramatically portrays the continuing battle of nature against human frailty, both physical and spiritual. The frightened and overwhelmed disciples struggle to retain control of their fishing boat as huge waves crash over the bow. One disciple is hanging over the side of the boat vomiting. A sail is torn, rope lines are flying loose, disaster is imminent as rocks appear in the left foreground. The dark clouds, the wind, the waves combine to create the terror of the painting and the terror of the disciples. Nature’s upheaval is the cause of, as well as a metaphor for, the fear that grips the disciples. The emotional turbulence is magni- fied by the dramatic impact of the painting, approximately 4’ wide by 5’ high. Jesus, whose face is lightened in the group on the right, remains calm. He woke up and rebuked the wind, and said to the sea, “Peace! Be still!” Then the wind ceased, and there was a dead calm, and he asked the disciples, “Why are you afraid? Have you still no faith?” The face of a 13th disciple looks directly out at the viewer in the horizontal center of the painting. -

16 Exhibition on Screen

Exhibition on Screen - The Impressionists – And the Man Who Made Them 2015, Run Time 97 minutes An eagerly anticipated exhibition travelling from the Musee d'Orsay Paris to the National Gallery London and on to the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the focus of the most comprehensive film ever made about the Impressionists. The exhibition brings together Impressionist art accumulated by Paul Durand-Ruel, the 19th century Parisian art collector. Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, are among the artists that he helped to establish through his galleries in London, New York and Paris. The exhibition, bringing together Durand-Ruel's treasures, is the focus of the film, which also interweaves the story of Impressionism and a look at highlights from Impressionist collections in several prominent American galleries. Paintings: Rosa Bonheur: Ploughing in Nevers, 1849 Constant Troyon: Oxen Ploughing, Morning Effect, 1855 Théodore Rousseau: An Avenue in the Forest of L’Isle-Adam, 1849 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Gleaners, 1857 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Angelus, c. 1857-1859 (Barbizon School) Charles-François Daubigny: The Grape Harvest in Burgundy, 1863 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: Spring, 1868-1873 (Barbizon School) Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: Ruins of the Château of Pierrefonds, c. 1830-1835 Théodore Rousseau: View of Mont Blanc, Seen from La Faucille, c. 1863-1867 Eugène Delecroix: Interior of a Dominican Convent in Madrid, 1831 Édouard Manet: Olympia, 1863 Pierre Auguste Renoir: The Swing, 1876 16 Alfred Sisley: Gateway to Argenteuil, 1872 Édouard Manet: Luncheon on the Grass, 1863 Edgar Degas: Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, 1874 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Ball at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, 1875 Alexandre Cabanel: The Birth of Venus, 1863 Édouard Manet: The Fife Player, 1866 Édouard Manet: The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), 1866 Henri Fantin-Latour: A Studio in the Batingnolles, 1870 Claude Monet: The Thames below Westminster, c. -

NINETEENTH-Century EUROPEAN PAINTINGS at the STERLING

Introduction Introduction Sterling and Francine clark art inStitute | WilliamStoWn, massachuSettS NINETEENTH-CENTURY EUROPEAN PAINTINGS diStributed by yale univerSity Press | NeW haven and london AT THE STERLING AND FRANCINE CLARK ART INSTITUTE VOLUME TWO Edited by Sarah Lees With an essay by Richard Rand and technical reports by Sandra L. Webber With contributions by Katharine J. Albert, Philippe Bordes, Dan Cohen, Kathryn Calley Galitz, Alexis Goodin, Marc Gotlieb, John House, Simon Kelly, Richard Kendall, Kathleen M. Morris, Leslie Hill Paisley, Kelly Pask, Elizabeth A. Pergam, Kathryn A. Price, Mark A. Roglán, James Rosenow, Zoë Samels, and Fronia E. Wissman 4 5 Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Francine Clark Art Institute is published with the assistance of the Getty Foundation and support from the National Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. Endowment for the Arts. Nineteenth-century European paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute / edited by Sarah Lees ; with an essay by Richard Rand and technical reports by Sandra L. Webber ; with contributions by Katharine J. Albert, Philippe Bordes, Dan Cohen, Kathryn Calley Galitz, Alexis Goodin, Marc Gotlieb, John House, Simon Kelly, Richard Kendall, Kathleen M. Morris, Leslie Hill Paisley, Kelly Pask, Elizabeth A. Produced by the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Pergam, Kathryn A. Price, Mark A. Roglán, James Rosenow, 225 South Street, Williamstown, Massachusetts 01267 Zoë Samels, Fronia E. Wissman. www.clarkart.edu volumes cm Includes bibliographical references and index. Curtis R. Scott, Director of Publications ISBN 978-1-935998-09-9 (clark hardcover : alk. paper) — and Information Resources ISBN 978-0-300-17965-1 (yale hardcover : alk. -

Grade 2, Lesson 4, Monet

1 Second Grade Print Les Arceaux Fleuris, Giverny, 1913 (The Flowering Arches) By Claude Monet (1840-1926) Technique: oil on canvas Size: 36 ¾” x 36 ¼” Collection: The Phoenix Art Museum Art Style and Genre: French Impressionist-landscape OBJECTIVES: ✦The students will be introduced to the work of Claude Monet. ✦The students will be introduced to Monetʼs vital role in the development of Impressionist art style. ✦The students will describe how Impressionist artist visualize the effects of light and atmosphere on natural forms. ✦The students will describe how Monetʼs garden at Giverny inspired his work. ✦The students will analyze Monetʼs use of complementary colors to add visual interest in the landscape. ✦The students will create an outdoor garden scene that demonstrates Impressionistic technique. ABOUT THE ARTIST: Claude Monet was born in Paris, France, in 1840. He moved with his family to the port city of Le Havre in 1845. By age fifteen, he had established himself as a local caricaturist. It was during this time that he attracted the attention of French landscape artist Eugene Boudin. From Boudin, Monet was introduced to plein-air (open air) painting and the pure beauty found in nature. His aspiration to pursue a life as an artist confirmed, Monet left for Paris against his familyʼs wishes. At age twenty, Monet served in the French army and requested duty in an African regiment. Exposed to intense light and color while in North Africa, the artist once remarked that they “...contained the germ of my future researches.” In 1862, Monet convinced his father of his commitment to painting and obtained his permission to study art in Paris at the atelier (studio) of painter/teacher Charles Gleyre. -

Masterpiece: Monet Painting in His Garden, 1913 by Pierre Auguste Renoir

Masterpiece: Monet Painting in His Garden, 1913 by Pierre Auguste Renoir Pronounced: REN WAUR Keywords: Impressionism, Open Air Painting Grade: 3rd Grade Month: November Activity: “Plein Air” Pastel Painting TIME: 1 - 1.25 hours Overview of the Impressionism Art Movement: Impressionism was a style of painting that became popular over 100 years ago mainly in France. Up to this point in the art world, artists painted people and scenery in a realistic manner. A famous 1872 painting by Claude Monet named “Impression: Sunrise ” was the inspiration for the name given to this new form of painting: “Impressionism” (See painting below) by an art critic. Originally the term was meant as an insult, but Monet embraced the name. The art institutes of the day thought that the paintings looked unfinished, or childlike. Characteristics of Impressionist paintings include: visible brush strokes, open composition, light depicting the effects of the passage of time, ordinary subject matter, movement, and unusual visual angles. As a technique, impressionists used dabs of paint (often straight out of a paint tube) to recreate the impression they saw of the light and the effects the light had on color. Due to this, most Impressionistic artists painted in the “plein-air”, French for open air. The important concept for 3 rd grade lessons is the Impressionism movement was short lived but inspired other artists from all over, including America, to begin using this new technique. Each of the artists throughout the lessons brought something new and a little different to advance the Impressionistic years. (i.e. Seurat with Neo-Impressionism and Toulouse-Lautrec with Post-Impressionism). -

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Caroline Mc Corriston Claude Monet (1840-1926) ● Monet was the leading figure of the impressionist group. ● As a teenager in Normandy he was brought to paint outdoors by the talented painter Eugéne Boudin. Boudin taught him how to use oil paints. ● Monet was constantly in financial difficulty. His paintings were rejected by the Salon and critics attacked his work. ● Monet went to Paris in 1859. He befriended the artists Cézanne and Pissarro at the Academie Suisse. (an open studio were models were supplied to draw from and artists paid a small fee).He also met Courbet and Manet who both encouraged him. ● He studied briefly in the teaching studio of the academic history painter Charles Gleyre. Here he met Renoir and Sisley and painted with them near Barbizon. ● Every evening after leaving their studies, the students went to the Cafe Guerbois, where they met other young artists like Cezanne and Degas and engaged in lively discussions on art. ● Monet liked Japanese woodblock prints and was influenced by their strong colours. He built a Japanese bridge at his home in Giverny. Monet and Impressionism ● In the late 1860s Monet and Renoir painted together along the Seine at Argenteuil and established what became known as the Impressionist style. ● Monet valued spontaneity in painting and rejected the academic Salon painters’ strict formulae for shading, geometrically balanced compositions and linear perspective. ● Monet remained true to the impressionist style but went beyond its focus on plein air painting and in the 1890s began to finish most of his work in the studio. Personal Style and Technique ● Use of pure primary colours (straight from the tube) where possible ● Avoidance of black ● Addition of unexpected touches of primary colours to shadows ● Capturing the effect of sunlight ● Loose brushstrokes Subject Matter ● Monet painted simple outdoor scenes in the city, along the coast, on the banks of the Seine and in the countryside. -

OF Versailles

THE CHÂTEAU DE VErSAILLES PrESENTS science & CUrIOSITIES AT THE COUrT OF versailles AN EXHIBITION FrOM 26 OCTOBEr 2010 TO 27 FEBrUArY 2011 3 Science and Curiosities at the Court of Versailles CONTENTS IT HAPPENED AT VErSAILLES... 5 FOrEWOrD BY JEAN-JACqUES AILLAGON 7 FOrEWOrD BY BÉATrIX SAULE 9 PrESS rELEASE 11 PArT I 1 THE EXHIBITION - Floor plan 3 - Th e exhibition route by Béatrix Saule 5 - Th e exhibition’s design 21 - Multimedia in the exhibition 22 PArT II 1 ArOUND THE EXHIBITION - Online: an Internet site, and TV web, a teachers’ blog platform 3 - Publications 4 - Educational activities 10 - Symposium 12 PArT III 1 THE EXHIBITION’S PArTNErS - Sponsors 3 - Th e royal foundations’ institutional heirs 7 - Partners 14 APPENDICES 1 USEFUL INFOrMATION 3 ILLUSTrATIONS AND AUDIOVISUAL rESOUrCES 5 5 Science and Curiosities at the Court of Versailles IT HAPPENED AT VErSAILLES... DISSECTION OF AN Since then he has had a glass globe made that ELEPHANT WITH LOUIS XIV is moved by a big heated wheel warmed by holding IN ATTENDANCE the said globe in his hand... He performed several experiments, all of which were successful, before Th e dissection took place at Versailles in January conducting one in the big gallery here... it was 1681 aft er the death of an elephant from highly successful and very easy to feel... we held the Congo that the king of Portugal had given hands on the parquet fl oor, just having to make Louis XIV as a gift : “Th e Academy was ordered sure our clothes did not touch each other.” to dissect an elephant from the Versailles Mémoires du duc de Luynes Menagerie that had died; Mr. -

Giving a Good Impressionism

Program Tuition The Parsippany~Troy Hills Live Well, Age Smart! Public Library System Fall 2016 Lecture Series Inclusive fee for all 4 sessions: $25 www.parsippanylibrary.org October 7, 14, 21, 28 This fee will help us to cover the cost of our Main Library speaker and materials. 449 Halsey Road Giving a Good Please make your check payable to: Parsippany, NJ 07054 “Parsippany Public Library Foundation” 973-887-5150 Impressionism Registration is open until October 6, 2016 Lake Hiawatha Branch You may either mail your registration to 68 Nokomis Avenue Speaker: Dr. Michael Norris Parsippany-Troy Hills Public Library Founda- Lake Hiawatha, NJ 07034 Metropolitan Museum of tion, Attn: Stephanie Kip. 973-335-0952 Art Educator 449 Halsey Road, Parsippany, NJ 07054 or Mount Tabor Branch drop it off at any of our library locations. 31 Trinity Park Name: _________________________________ Mount Tabor, NJ 07878 Parsippany~Troy Hills Public Library 973-627-9508 449 Halsey Road Address:_________________________________ Parsippany, NJ 07054 _________________________________ 973-887-5150 www.parsippanylibrary.org Phone: _________________________________ Email: _________________________________ Please check: _____ I would like to receive information about future Live Well, Age Smart programs _____ I would also like to receive information about ongoing programs. The library is the of your community! About Live Well, Class Information Presenter Biography Age Smart Live Well, Age Smart is an ongoing series Friday, October 7, 2:00-3:30 pm Dr. Michael Norris that provides creative learning opportuni- A New French Revolution: Impressionism ties to the Parsippany area community. Uti- in Art lizing collegiate level speakers, the series Learn how influences from Japan, a fascina- Dr. -

DUTCH and ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850

DUTCH AND ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850 The art and ship models in this station are devoted to the early Dutch and English seascape painters. The historical emphasis here explains the importance of the sea to these nations. Historical Overview: The Dutch: During the 17th century, the Netherlands emerged as one of the great maritime oriented empires. The Dutch Republic was born in 1579 with the signing of the Union of Utrecht by the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands. Two years later the United Provinces of the Netherlands declared their independence from the Spain. They formed a loose confederation as a representative body that met in The Hague where they decided on issues of taxation and defense. During their heyday, the Dutch enjoyed a worldwide empire, dominated international trade and built the strongest economy in Europe on the foundation of a powerful merchant class and a republican form of government. The Dutch economy was based on a mutually supportive industry of agriculture, fishing and international cargo trading. At their command was a huge navy and merchant fleet of fluyts, cargo ships specially designed to sail through the world, which controlled a large percentage of the international trade. In 1595 the first Dutch ships sailed for the East Indies. The Dutch East Indies Company (the VOC as it was known) was established in 1602 and competed directly with Spain and Portugal for the spices of the Far East and the Indian subcontinent. The success of the VOC encouraged the Dutch to expand to the Americas where they established colonies in Brazil, Curacao and the Virgin Islands. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p.