Population, Phylogenetic, and Coalescent Analyses of Character Evolution in Gossamer- Winged Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butterflies of Ontario & Summaries of Lepidoptera

ISBN #: 0-921631-12-X BUTTERFLIES OF ONTARIO & SUMMARIES OF LEPIDOPTERA ENCOUNTERED IN ONTARIO IN 1991 BY A.J. HANKS &Q.F. HESS PRODUCTION BY ALAN J. HANKS APRIL 1992 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION PAGE 1 2. WEATHER DURING THE 1991 SEASON 6 3. CORRECTIONS TO PREVIOUS T.E.A. SUMMARIES 7 4. SPECIAL NOTES ON ONTARIO LEPIDOPTERA 8 4.1 The Inornate Ringlet in Middlesex & Lambton Cos. 8 4.2 The Monarch in Ontario 8 4.3 The Status of the Karner Blue & Frosted Elfin in Ontario in 1991 11 4.4 The West Virginia White in Ontario in 1991 11 4.5 Butterfly & Moth Records for Kettle Point 11 4.6 Butterflies in the Hamilton Study Area 12 4.7 Notes & Observations on the Early Hairstreak 15 4.8 A Big Day for Migrants 16 4.9 The Ocola Skipper - New to Ontario & Canada .17 4.10 The Brazilian Skipper - New to Ontario & Canada 19 4.11 Further Notes on the Zarucco Dusky Wing in Ontario 21 4.12 A Range Extension for the Large Marblewing 22 4.13 The Grayling North of Lake Superior 22 4.14 Description of an Aberrant Crescent 23 4.15 A New Foodplant for the Old World Swallowtail 24 4.16 An Owl Moth at Point Pelee 25 4.17 Butterfly Sampling in Algoma District 26 4.18 Record Early Butterfly Dates in 1991 26 4.19 Rearing Notes from Northumberland County 28 5. GENERAL SUMMARY 29 6. 1990 SUMMARY OF ONTARIO BUTTERFLIES, SKIPPERS & MOTHS 32 Hesperiidae 32 Papilionidae 42 Pieridae 44 Lycaenidae 48 Libytheidae 56 Nymphalidae 56 Apaturidae 66 Satyr1dae 66 Danaidae 70 MOTHS 72 CONTINUOUS MOTH CYCLICAL SUMMARY 85 7. -

Frontiers in Zoology Biomed Central

Frontiers in Zoology BioMed Central Research Open Access Does the DNA barcoding gap exist? – a case study in blue butterflies (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) Martin Wiemers* and Konrad Fiedler Address: Department of Population Ecology, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Email: Martin Wiemers* - [email protected]; Konrad Fiedler - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 7 March 2007 Received: 1 December 2006 Accepted: 7 March 2007 Frontiers in Zoology 2007, 4:8 doi:10.1186/1742-9994-4-8 This article is available from: http://www.frontiersinzoology.com/content/4/1/8 © 2007 Wiemers and Fiedler; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: DNA barcoding, i.e. the use of a 648 bp section of the mitochondrial gene cytochrome c oxidase I, has recently been promoted as useful for the rapid identification and discovery of species. Its success is dependent either on the strength of the claim that interspecific variation exceeds intraspecific variation by one order of magnitude, thus establishing a "barcoding gap", or on the reciprocal monophyly of species. Results: We present an analysis of intra- and interspecific variation in the butterfly family Lycaenidae which includes a well-sampled clade (genus Agrodiaetus) with a peculiar characteristic: most of its members are karyologically differentiated from each other which facilitates the recognition of species as reproductively isolated units even in allopatric populations. -

African Butterfly News Can Be Downloaded Here

LATE SUMMER EDITION: JANUARY / AFRICAN FEBRUARY 2018 - 1 BUTTERFLY THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY OF AFRICA NEWS LATEST NEWS Welcome to the first newsletter of 2018! I trust you all have returned safely from your December break (assuming you had one!) and are getting into the swing of 2018? With few exceptions, 2017 was a very poor year butterfly-wise, at least in South Africa. The drought continues to have a very negative impact on our hobby, but here’s hoping that 2018 will be better! Braving the Great Karoo and Noorsveld (Mark Williams) In the first week of November 2017 Jeremy Dobson and I headed off south from Egoli, at the crack of dawn, for the ‘Harde Karoo’. (Is there a ‘Soft Karoo’?) We had a very flexible plan for the six-day trip, not even having booked any overnight accommodation. We figured that finding a place to commune with Uncle Morpheus every night would not be a problem because all the kids were at school. As it turned out we did not have to spend a night trying to kip in the Pajero – my snoring would have driven Jeremy nuts ... Friday 3 November The main purpose of the trip was to survey two quadrants for the Karoo BioGaps Project. One of these was on the farm Lushof, 10 km west of Loxton, and the other was Taaiboschkloof, about 50 km south-east of Loxton. The 1 000 km drive, via Kimberley, to Loxton was accompanied by hot and windy weather. The temperature hit 38 degrees and was 33 when the sun hit the horizon at 6 pm. -

PRAVILNIK O PREKOGRANIĈNOM PROMETU I TRGOVINI ZAŠTIĆENIM VRSTAMA ("Sl

PRAVILNIK O PREKOGRANIĈNOM PROMETU I TRGOVINI ZAŠTIĆENIM VRSTAMA ("Sl. glasnik RS", br. 99/2009 i 6/2014) I OSNOVNE ODREDBE Ĉlan 1 Ovim pravilnikom propisuju se: uslovi pod kojima se obavlja uvoz, izvoz, unos, iznos ili tranzit, trgovina i uzgoj ugroţenih i zaštićenih biljnih i ţivotinjskih divljih vrsta (u daljem tekstu: zaštićene vrste), njihovih delova i derivata; izdavanje dozvola i drugih akata (potvrde, sertifikati, mišljenja); dokumentacija koja se podnosi uz zahtev za izdavanje dozvola, sadrţina i izgled dozvole; spiskovi vrsta, njihovih delova i derivata koji podleţu izdavanju dozvola, odnosno drugih akata; vrste, njihovi delovi i derivati ĉiji je uvoz odnosno izvoz zabranjen, ograniĉen ili obustavljen; izuzeci od izdavanja dozvole; naĉin obeleţavanja ţivotinja ili pošiljki; naĉin sprovoĊenja nadzora i voĊenja evidencije i izrada izveštaja. Ĉlan 2 Izrazi upotrebljeni u ovom pravilniku imaju sledeće znaĉenje: 1) datum sticanja je datum kada je primerak uzet iz prirode, roĊen u zatoĉeništvu ili veštaĉki razmnoţen, ili ukoliko takav datum ne moţe biti dokazan, sledeći datum kojim se dokazuje prvo posedovanje primeraka; 2) deo je svaki deo ţivotinje, biljke ili gljive, nezavisno od toga da li je u sveţem, sirovom, osušenom ili preraĊenom stanju; 3) derivat je svaki preraĊeni deo ţivotinje, biljke, gljive ili telesna teĉnost. Derivati većinom nisu prepoznatljivi deo primerka od kojeg potiĉu; 4) država porekla je drţava u kojoj je primerak uzet iz prirode, roĊen i uzgojen u zatoĉeništvu ili veštaĉki razmnoţen; 5) druga generacija potomaka -

Genomic Analysis of the Tribe Emesidini (Lepidoptera: Riodinidae)

Zootaxa 4668 (4): 475–488 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4668.4.2 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:211AFB6A-8C0A-4AB2-8CF6-981E12C24934 Genomic analysis of the tribe Emesidini (Lepidoptera: Riodinidae) JING ZHANG1, JINHUI SHEN1, QIAN CONG1,2 & NICK V. GRISHIN1,3 1Departments of Biophysics and Biochemistry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and 3Howard Hughes Medical Insti- tute, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX, USA 75390-9050; [email protected] 2present address: Institute for Protein Design and Department of Biochemistry, University of Washington, 1959 NE Pacific Street, HSB J-405, Seattle, WA, USA 98195; [email protected] Abstract We obtained and phylogenetically analyzed whole genome shotgun sequences of nearly all species from the tribe Emesidini Seraphim, Freitas & Kaminski, 2018 (Riodinidae) and representatives from other Riodinidae tribes. We see that the recently proposed genera Neoapodemia Trujano, 2018 and Plesioarida Trujano & García, 2018 are closely allied with Apodemia C. & R. Felder, [1865] and are better viewed as its subgenera, new status. Overall, Emesis Fabricius, 1807 and Apodemia (even after inclusion of the two subgenera) are so phylogenetically close that several species have been previously swapped between these two genera. New combinations are: Apodemia (Neoapodemia) zela (Butler, 1870), Apodemia (Neoapodemia) ares (Edwards, 1882), and Apodemia (Neoapodemia) arnacis (Stichel, 1928) (not Emesis); and Emesis phyciodoides (Barnes & Benjamin, 1924) (not Apodemia), assigned to each genus by their monophyly in genomic trees with the type species (TS) of the genus. -

Plant Inventory at Missouri National Recreational River

Inventory of Butterflies at Fort Union Trading Post and Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Sites in 2004 --<o>-- Final Report Submitted by: Ronald Alan Royer, Ph.D. Burlington, North Dakota 58722 Submitted to: Northern Great Plains Inventory & Monitoring Coordinator National Park Service Mount Rushmore National Memorial Keystone, South Dakota 57751 October 1, 2004 Executive Summary This document reports inventory of butterflies at Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site (NHS) and Fort Union Trading Post NHS, both administered by the National Park Service in the state of North Dakota. Field work consisted of strategically timed visits throughout Summer 2004. The inventory employed “checklist” counting based on the author's experience with habitat for the various species expected from each site. This report is written in two separate parts, one for each site. Each part contains an annotated species list for that site. For possible later GIS use, noteworthy species encounters are reported by UTM coordinates, all of which are provided conveniently in a table within the report narrative for each site. An annotated listing is also included for each species at each site. Each of these provides a brief description of typical habitat, principal larval host(s), and information on adult phenology. This information is followed by abbreviated citations for published works in which more detailed information may be located. Recommendations are then made for each site on the basis of endemism, prairie butterfly conservation and -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

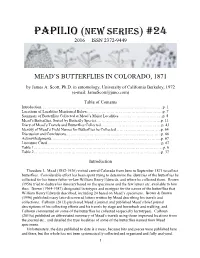

Papilio (New Series) #24 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) #24 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 MEAD’S BUTTERFLIES IN COLORADO, 1871 by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology, University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………..……….……………….p. 1 Locations of Localities Mentioned Below…………………………………..……..……….p. 7 Summary of Butterflies Collected at Mead’s Major Localities………………….…..……..p. 8 Mead’s Butterflies, Sorted by Butterfly Species…………………………………………..p. 11 Diary of Mead’s Travels and Butterflies Collected……………………………….……….p. 43 Identity of Mead’s Field Names for Butterflies he Collected……………………….…….p. 64 Discussion and Conclusions………………………………………………….……………p. 66 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….……………...p. 67 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………….………...….p. 67 Table 1………………………………………………………………………….………..….p. 6 Table 2……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 37 Introduction Theodore L. Mead (1852-1936) visited central Colorado from June to September 1871 to collect butterflies. Considerable effort has been spent trying to determine the identities of the butterflies he collected for his future father-in-law William Henry Edwards, and where he collected them. Brown (1956) tried to deduce his itinerary based on the specimens and the few letters etc. available to him then. Brown (1964-1987) designated lectotypes and neotypes for the names of the butterflies that William Henry Edwards described, including 24 based on Mead’s specimens. Brown & Brown (1996) published many later-discovered letters written by Mead describing his travels and collections. Calhoun (2013) purchased Mead’s journal and published Mead’s brief journal descriptions of his collecting efforts and his travels by stage and horseback and walking, and Calhoun commented on some of the butterflies he collected (especially lectotypes). Calhoun (2015a) published an abbreviated summary of Mead’s travels using those improved locations from the journal etc., and detailed the type localities of some of the butterflies named from Mead specimens. -

Vascular Plants and a Brief History of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands

United States Department of Agriculture Vascular Plants and a Brief Forest Service Rocky Mountain History of the Kiowa and Rita Research Station General Technical Report Blanca National Grasslands RMRS-GTR-233 December 2009 Donald L. Hazlett, Michael H. Schiebout, and Paulette L. Ford Hazlett, Donald L.; Schiebout, Michael H.; and Ford, Paulette L. 2009. Vascular plants and a brief history of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-233. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 44 p. Abstract Administered by the USDA Forest Service, the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands occupy 230,000 acres of public land extending from northeastern New Mexico into the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. A mosaic of topographic features including canyons, plateaus, rolling grasslands and outcrops supports a diverse flora. Eight hundred twenty six (826) species of vascular plant species representing 81 plant families are known to occur on or near these public lands. This report includes a history of the area; ethnobotanical information; an introductory overview of the area including its climate, geology, vegetation, habitats, fauna, and ecological history; and a plant survey and information about the rare, poisonous, and exotic species from the area. A vascular plant checklist of 816 vascular plant taxa in the appendix includes scientific and common names, habitat types, and general distribution data for each species. This list is based on extensive plant collections and available herbarium collections. Authors Donald L. Hazlett is an ethnobotanist, Director of New World Plants and People consulting, and a research associate at the Denver Botanic Gardens, Denver, CO. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

Report on the Butterflies Collected from Chongqing, Shaanxi and Gansu

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Atalanta Jahr/Year: 2016 Band/Volume: 47 Autor(en)/Author(s): Huang Si-Yao Artikel/Article: Report on the butterflies collected from Chongqing, Shaanxi and Gansu, China in 2015 (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea, Hesperoidea) 241-248 Atalanta 47 (1/2): 241-248, Marktleuthen (Juli 2016), ISSN 0171-0079 Report on the butterflies collected from Chongqing, Shaanxi and Gansu, China in 2015 (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea, Hesperoidea) by SI-YAO HUANG received 30.III.2016 Abstract: A list of the butterflies collected by the author and his colleague in the Chinese Provinces of Chongqing, S. Shaanxi and S. Gansu in the summer of 2015 is presented. In the summer of 2015, the author accomplished a survey on butterflies at the following localities (fig. A): Chongqing Province: Simianshan, 4th-9thJuly. Shaanxi Province: Liping Natural Reserve, Nanzheng County: 12th-14th July; Danangou, Fengxian County: 31st July; Dongshan, Taibai County: 1st August; Miaowangshan, Fengxian County: 2nd August; Xiaonangou, Fengxian County: 3rd-5th August; Zhufeng, Fengxian County: 5th August. Gansu Province: Xiongmaogou, Xiahe County: 16th-18th July; Laolonggou, Diebu County: 20th July; Meilugou, Die- bu County: 21st July; Tiechiliang, Diebu County: 22nd July; Lazikou, Diebu County: 23rd July; Tiangangou, Zhouqu County: 25th-26th July; Pianpiangou, Zhouqu County: 28th-29th July. A checklist of butterflies collected from Chongqing, Shaanxi and Gansu in 2015 Hesperiidae Coeliadinae 1. Hasora tarminatus (HÜBNER, 1818): 1 † 7-VII, Simianshan, leg. & coll. GUO-XI XUE. Pyrginae 2. Gerosis phisara (MOORE, 1884): 1 †, 6-VII, Simianshan. 3. Celaenorrhinus maculosus (C. & R. -

Amphiesmeno- Ptera: the Caddisflies and Lepidoptera

CY501-C13[548-606].qxd 2/16/05 12:17 AM Page 548 quark11 27B:CY501:Chapters:Chapter-13: 13Amphiesmeno-Amphiesmenoptera: The ptera:Caddisflies The and Lepidoptera With very few exceptions the life histories of the orders Tri- from Old English traveling cadice men, who pinned bits of choptera (caddisflies)Caddisflies and Lepidoptera (moths and butter- cloth to their and coats to advertise their fabrics. A few species flies) are extremely different; the former have aquatic larvae, actually have terrestrial larvae, but even these are relegated to and the latter nearly always have terrestrial, plant-feeding wet leaf litter, so many defining features of the order concern caterpillars. Nonetheless, the close relationship of these two larval adaptations for an almost wholly aquatic lifestyle (Wig- orders hasLepidoptera essentially never been disputed and is supported gins, 1977, 1996). For example, larvae are apneustic (without by strong morphological (Kristensen, 1975, 1991), molecular spiracles) and respire through a thin, permeable cuticle, (Wheeler et al., 2001; Whiting, 2002), and paleontological evi- some of which have filamentous abdominal gills that are sim- dence. Synapomorphies linking these two orders include het- ple or intricately branched (Figure 13.3). Antennae and the erogametic females; a pair of glands on sternite V (found in tentorium of larvae are reduced, though functional signifi- Trichoptera and in basal moths); dense, long setae on the cance of these features is unknown. Larvae do not have pro- wing membrane (which are modified into scales in Lepi- legs on most abdominal segments, save for a pair of anal pro- doptera); forewing with the anal veins looping up to form a legs that have sclerotized hooks for anchoring the larva in its double “Y” configuration; larva with a fused hypopharynx case.