Stein, Green, Lapinski II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, the "Alternative" Western, and the American Romance Tradition

Journal X Volume 7 Number 1 Autumn 2002 Article 5 2020 Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, the "Alternative" Western, and the American Romance Tradition Steven Frye California State University, Bakersfield Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jx Part of the American Film Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frye, Steven (2020) "Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, the "Alternative" Western, and the American Romance Tradition," Journal X: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jx/vol7/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal X by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frye: Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, the "Alternative" Western, and the A Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, the "Alternative" Western, and the American Romance Tradition Steven Frye Steven Frye is Asso Much criticism of Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven ciate Professor of focuses on the way the film dismantles or decon English at structs traditional western myths. Maurice California State Yacowar argues that Unforgiven is a myth "disre- University, Bakers membered and rebuilt, to express a contempo field, and author of Historiography rary understanding of what the west and the and Narrative Western now mean" (247). Len Engel explores Design in the the film's mythopoetic nature, stating that direc American tor Eastwood and scriptwriter David Webb Peo Romance: A Study ples "undermine traditional myths" in a tale of Four Authors that evokes Calvinist undertones of predestina (2001). tion (261). Leighton Grist suggests that the film "problematizes the familiar ideological assump tions of the genre" (294). -

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’S Impact on the Western

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’s Impact on the Western Jacob A. Williams A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2012 Committee: Claudia Gorbman E. Joseph Sharkey Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Section I The Anti-Hero: Newborn or Reborn Hero? 4 Section II A Greek Tradition: Violence as Catharsis 11 Section III The Theseus Theory 21 Section IV A Modern Greek Tale: The Outlaw Josey Wales 31 Section V The Euripides Effect: Bringing the Audience on Stage 40 Section VI The Importance of the Western Myth 47 Section VII Conclusion: The Immortality of the Western 49 Bibliography 53 Sources Cited 62 i Dedication To my wife and children, whom I cherish every day: To Brandy, for always being the one person I can always count on, and for supporting me through this entire process. You are my love and my life. I couldn’t have done any of this without you. To Andrew, for always being so responsible, being an awesome big brother to your siblings, and always helping me whenever I need you. You are a good son, and I am proud of the man you are becoming. To Tristan, for always being my best friend, and my son. You never cease to amaze and inspire me. Your creativity exceeds my own. To Gracie, for being my happy “Pretty Princess.” Thank you for allowing me to see the world through the eyes of a nature-loving little girl. -

'Pale Rider' Is Clint Eastwood's First Western Film Since He Starred in and Directed "The Outlaw Josey Wales" in 1976

'Pale Rider' is Clint Eastwood's first Western film since he starred in and directed "The Outlaw Josey Wales" in 1976. Eastwood plays a nameless stranger who rides into the gold rush town of LaHood, California and comes to the aid of a group of independent gold prospectors who are being threatened by the LaHood mining corporation. The independent miners hold claims to a region called Carbon Canyon, the last of the potentially ore-laden areas in the county. Coy LaHood wants to dredge Carbon Canyon and needs the independent miners out LaHood hires the county marshal, a gunman named Stockburn with six deputies, to get the job done. What neither LaHood nor Stockburn could possibly have taken into consideration is the appearance of the enigmatic horseman and the fate awaiting them. This study guide attempts to place 'Pale Rider' within the Western genre and also within the canon of Eastwood's films. We would suggest that the work on Film genre and advertising are completed before students see 'Pale Rider'. FILM GENRE The word "genre" might well be unfamiliar to you. It is a French word which means "type" and so when we talk of film genre we mean type of film. The western is one particular genre which we will be looking at in detail in this study guide. What other types of genre are there in film? Horror is one. Task One Write a list of all the different film genres that you can think of. When you have done this, try to write a list of genres that you might find in literature. -

El Sueño Y El Recuerdo En High Plains Drifter: Incertidumbre Y Reflectáforas Revista De Humanidades: Tecnológico De Monterrey, Núm

Revista de Humanidades: Tecnológico de Monterrey ISSN: 1405-4167 [email protected] Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey México Lema, Rose El sueño y el recuerdo en High Plains Drifter: incertidumbre y reflectáforas Revista de Humanidades: Tecnológico de Monterrey, núm. 19, otoño, 2005, pp. 193-213 Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey Monterrey, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=38401909 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto El sueno y el recuerdo en High Plains Drifter: incertidumbre y reflectaforas Rose Lema UAM-Iztapalapa El artículo presenta una lectura, el análisis y la interpretación de tres episodios de High Plains Drifter (Clint Eastwood, 1972), que tienen que ver con lo sobrenatural como valor prominente de la película. El primer episodio corresponde al genérico y las tumbas; el segundo, al sueño; el tercero, al recuerdo. Se toman en cuenta tanto la dinámica sonora como la visual, así como la zona interfásica en que se generan. Sin sobrevalorar a una u otra, ya que se conciben como procesos que el realizador combina, administrándolos y relativizándolos organizadamente. Se interpretan los episodios y las nociones teóricas, mediante la noción de reflectáfora, proveniente de las teorías del caos y la complejidad. This article presents the analysis and the interpretation of three episodes in High Plains Drifter (Clint Eastwood 1972), which have to do with the supernatural as a prominent value of the film. -

Angela M. Ross

The Princess Production: Locating Pocahontas in Time and Place Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ross, Angela Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 20:51:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194511 THE PRINCESS PRODUCTION: LOCATING POCAHONTAS IN TIME AND PLACE by Angela M. Ross ________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE CULTURAL AND LITERARY STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2008 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Angela Ross entitled The Princess Production: Locating Pocahontas in Time and Place and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/03/2008 Susan White _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/03/2008 Laura Briggs _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/03/2008 Franci Washburn Final approval -

Cultural and Religious Reversals in Clint Eastwood's Gran Torino

RELIGION and the ARTS Religion and the Arts 15 (2011) 648–679 brill.nl/rart Cultural and Religious Reversals in Clint Eastwood’s Gran Torino Mark W. Roche and Vittorio Hösle University of Notre Dame Abstract Clint Eastwood’s Gran Torino is one of the most fascinating religious films of recent decades. Its portrayal of confession is highly ambiguous and multi-layered, as it both mocks con- fession and recognizes the enduring importance of its moral core. Equally complex is the film’s imitation and reversal of the Christ story. The religious dimension is interwoven with a complex portrayal and evaluation of multicultural America that does not shy away from unveiling elements of moral ugliness in American history and the American spirit, even as it provides a redemptive image of American potential. The film reflects on the shallowness of a modern culture devoid of tradition and higher meaning without succumbing to an idealization of pre-modern culture. The film is also Eastwood’s deepest and most effective criticism of the relentless logic of violence and so reverses a common conception of East- wood’s world-view. Keywords Gran Torino, Clint Eastwood, film and religion, confession, violence, self-sacrifice, Christ, American identity, multiculturalism, redemption lint Eastwood’s standing as an actor and a director has received Cincreasing attention in recent years, not only in popular books, but also in scholarly works. A sign of Eastwood’s reputation is that both Unforgiven (1992), a revisionist Western, and Million Dollar Baby (2004), a film about a struggling female boxer and her moving relationship with her trainer, received Oscars for Best Director and Best Film as well as nominations for Best Actor. -

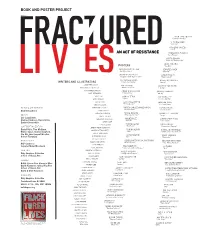

Book and Poster Project an Act of Resistance

BOOK AND POSTER PROJECT IGOR LANGSHTEYN “Secret Formulas” SEYOUNG PARK “Hard Hat” CAROLINA CAICEDO “Shell” AN ACT OF RESISTANCE FRANCESCA TODISCO “Up in Flames” CURTIS BROWN “Not in my Fracking City” WOW JUN CHOI POSTERS “Cracking” SAM VAN DEN TILLAAR JENNIFER CHEN “Fracktured Lives” “Dripping” ANDREW CASTRUCCI LINA FORSETH “Diagram: Rude Algae of Time” “Water Faucet” ALEXANDRA ROJAS NICHOLAS PRINCIPE WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS “Protect Your Mother” “Money” SARAH FERGUSON HYE OK ROW ANDREW CASTRUCCI ANN-SARGENT WOOSTER “Water Life Blood” “F-Bomb” KATHARINE DAWSON ANDREW CASTRUCCI MICHAEL HAFFELY MIKE BERNHARD “Empire State” “Liberty” YOKO ONO CAMILO TENSI JUN YOUNG LEE SEAN LENNON “Pipes” “No Fracking Way” AKIRA OHISO IGOR LANGSHTEYN MORGAN SOBEL “7 Deadly Sins” CRAIG STEVENS “Scull and Bones” EDITOR & ART DIRECTOR MARIANNE SOISALO KAREN CANALES MALDONADO JAYPON CHUNG “Bottled Water” Andrew Castrucci TONY PINOTTI “Life Fracktured” CARLO MCCORMICK MARIO NEGRINI GABRIELLE LARRORY DESIGN “This Land is Ours” “Drops” CAROL FRENCH Igor Langshteyn, TERESA WINCHESTER ANDREW LEE CHRISTOPHER FOXX Andrew Castrucci, Daniel Velle, “Drill Bit” “The Thinker” Daniel Giovanniello GERRI KANE TOM MCGLYNN TOM MCGLYNN KHI JOHNSON CONTRIBUTING EDITORS “Red Earth” “Government Warning” JEREMY WEIR ALDERSON Daniel Velle, Tom McGlynn, SANDRA STEINGRABER TOM MCGLYNN DANIEL GIOVANNIELLO Walter Sipser, Dennis Crawford, “Mob” “Make Sure to Put One On” ANTON VAN DALEN Jim Wu, Ann-Sargent Wooster, SOFIA NEGRINI ALEXANDRA ROJAS DAVID SANDLIN Robert Flemming “No” “Frackicide” -

BFI Annual Review 2008/2009

The following TiTles were screened as parT of various seasons and reTrospecTives aT The Bfi souThBank - april 2008 | PoP Goes the Revolution: FRench cinema and may ‘68 | alPhaville (1965) | the BRide WoRe Black / la maRiée était en noiR (1967) | la collectionneuse (1966) | un homme et une Femme (1966) | les idoles (1968) | masculin Féminin (1966) | mR FReedom (1968) | la Piscine (1968) | la Révolution n’est qu’un déBut. - continuons le comBat (1969) | sloGan (1969) | tRans-euRoP exPRess (1968) | Weekend (1967) | Who aRe you, Polly maGGoo? / qui êtes-vous, Polly maGGoo? (1966) RoBeRt donat | the 39 stePs (1935) | the adventuRes oF taRtu (1943) | the citadel (1938) | the count oF monte cRisto (1934) | the cuRe FoR love (1950) | the Ghost Goes West (1935) | GoodBye, mR. chiPs (1939) | the inn oF the sixth haPPiness (1958) | kniGht Without aRmouR (1937) | lease oF liFe (1954) | the maGic Box (1951) | PeRFect stRanGeRs (1945) | the PRivate liFe oF henRy viii (1933) | the WinsloW Boy (1948) | Rakhshan Bani-etemad | the Blue-veiled / RusaRi aBi (1994) | canaRy yelloW / ZaRd-e qaBaRu (1986) | centRalisation / tamaRkoZ (1987) | FoReiGn cuRRency / Pul-e khaReji (1989) | Gilaneh (2005) | the last meetinG With iRan daFtaRi / akhaRin didaR Ba iRan-e daFtaRi (1995) | mainline / khunBaZi (2006) | the may lady / Banu-ye oRdiBehest (1998) | naRGess (1992) | oFF-limits / khaRej as mahdudeh (1986) | ouR times / RuZeGaR-e ma (2002) | to Whom Will you shoW these Films anyWay? / in Filmha Ro Be ki neshun midin? (1993) | undeR the city’s skin / ZiR-e Pust-e -

XXIV:9) Clint Eastwood, the OUTLAW JOSEY WALES (1976, 135 Min.)

Please turn off cellphones during screening March 20, 2012 (XXIV:9) Clint Eastwood, THE OUTLAW JOSEY WALES (1976, 135 min.) Directed by Clint Eastwood Screenplay by Philip Kaufman and Sonia Chernus Based on the novel by Forrest Carter Produced by Robert Daley Original Music by Jerry Fielding Cinematography by Bruce Surtees Film Editing by Ferris Webster Clint Eastwood…Josey Wales Chief Dan George…Lone Watie Sondra Locke…Lee Bill McKinney…Terrill John Vernon…Fletcher Paula Trueman…Grandma Sarah Sam Bottoms...Jamie Geraldine Keams…Little Moonlight Woodrow Parfrey…Carpetbagger John Verros…Chato Will Sampson…Ten Bears John Quade…Comanchero Leader John Russell…Bloody Bill Anderson Charles Tyner…Zukie Limmer John Mitchum…Al Kyle Eastwood…Josey's Son Richard Farnsworth…Comanchero 1996 National Film Registry 1983 Sudden Impact, 1982 Honkytonk Man, 1982 Firefox, 1980 Bronco Billy, 1977 The Gauntlet, 1976 The Outlaw Josey Wales, 1975 The Eiger Sanction, 1973 Breezy, 1973 High Plains Drifter, Clint Eastwood (b. Clinton Eastwood Jr., May 31, 1930, San 1971 Play Misty for Me, and 1971 The Beguiled: The Storyteller. Francisco, California) has won five Academy Awards: best He has 67 acting credits, some of which are 2008 Gran Torino, director and best picture for Million Dollar Baby (2004), the 2004 Million Dollar Baby, 2000 Space Cowboys, 1999 True Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award (1995) and best director and Crime, 1997 Absolute Power, 1995 The Bridges of Madison best picture for Unforgiven (1992). He has directed 35 films, County, 1993 A Perfect -

Place Images of the American West in Western Films

PLACE IMAGES OF THE AMERICAN WEST IN WESTERN FILMS by TRAVIS W. SMITH B.S., Kansas State University, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2005 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Geography College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Abstract Hollywood Westerns have informed popular images of the American West for well over a century. This study of cultural, cinematic, regional, and historical geography examines place imagery in the Western. Echoing Blake’s (1995) examination of the novels of Zane Grey, the research questions analyze one hundred major Westerns to identify (1) the spatial settings (where the plot of the Western transpires), (2) the temporal settings (what date[s] in history the Western takes place), and (3) the filming locations. The results of these three questions illuminate significant place images of the West and the geography of the Western. I selected a filmography of one hundred major Westerns based upon twenty different Western film credentials. My content analysis involved multiple viewings of each Western and cross-referencing film content like narrative titles, American Indian homelands, fort names, and tombstone dates with scholarly and popular publications. The Western spatially favors Apachería, the Borderlands and Mexico, and the High Plains rather than the Pacific Northwest. Also, California serves more as a destination than a spatial setting. Temporally, the heart of the Western beats during the 1870s and 1880s, but it also lives well into the twentieth century. The five major filming location clusters are the Los Angeles / Hollywood area and its studio backlots, Old Tucson Studios and southeastern Arizona, the Alabama Hills in California, Monument Valley in Utah and Arizona, and the Santa Fe region in New Mexico. -

Double Features References

DOUBLE FEATURES BIG IDEAS IN FILM Reference List DOUBLE FEATURES BIG IDEAS IN FILM Reference List Yossarian Is Alive and Well in the Mexican Desert 4 Nora Ephron Countercultural Architecture and Dramatic Structure 6 David Mamet Shooting to Kill (selection) 7 Christine Vachon Laugh, Cry, Believe: Spielbergization and Its Discontents 10 J. Hoberman In the Blink of an Eye (selection) 15 Walter Murch “One Hang, We All Hang”: High Plains Drifter 16 Richard Hutson Lynch on Lynch (selection) 18 Chris Rodley, interview with David Lynch John Wayne: A Love Song 19 Joan Didion Nonstop Action: Why Hollywood’s Aging Heroes Won’t Give Up the Gun 20 Adam Mars-Jones Willing 23 Lorrie Moore The contents of this packet include proprietary trademarks and copyrighted materials, and may be used or quoted only with permission and appropriate credit to the Great Books Foundation. DOUBLE FEATURES Furiosa: The Virago of Mad Max: Fury Road 24 Jess Zimmerman Scary Movies 25 Kim Addonizio Skyshot 26 Manuel Muñoz Edward Hopper’s New York Movie 27 Joseph Stanton Why We Crave Horror Movies 28 Stephen King Matinée 32 Robert Coover The Last Movie 33 Rachel Hadas Some Months After My Father’s Death 34 Sheryl St. Germain The Birds (selection) 35 Camille Paglia Your Childhood Entertainment Is Not Sacred 37 Nathan Rabin Pygmalion’s Ghost: Female AI and Technological Dream Girls 38 Angelica Jade Bastién The Solace of Preparing Fried Foods and Other Quaint Remembrances from 1960s Mississippi: Thoughts on The Help 39 Roxane Gay Better Living Through Criticism: How to Think About Art, Pleasure, Beauty, and Truth (selection) 40 A. -

There's a Theremin on the Radio!

A monthly guide to your community library, its programs and services Issue No. 244, July 2009 Library schedule The library will be closed Saturday, There’s a Theremin on July 4. Beginning July 11, the library will be open 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. on Satur- days. The library will be open Satur- the Radio! days from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. beginning September 19. The library is closed on Guess what? “There’s a Ther- Theremin on the Radio! Sundays during the summer. emin on the Radio!” Everyone knows Thereminist Kip Rosser ap- what a radio is, but have you ever plies his delightful blend of music heard of the theremin? and madness to a twisted history of Derek Smith at Gala Invented between 1919 and the incredible relationship between The Library Foundation’s Sixth In- 1920, the theremin was the world’s the theremin and the radio . and spiration Gala, at the library on Sep- first fully electronic musical instru- himself. He tells it all through child- tember 12, will feature entertainment ment. Most astonishing, though, is hood musings and music, from clas- by Derek Smith. London-born Smith that it remains the only musical in- sic sci-fi movies to top 10 radio hits got his start in jazz with Johnny strument ever invented that is played like the Beach Boys’ classic, Good Dankworth’s fabled British big band. without being touched (trust us; you Vibrations. Described by critics as “fiery,” “pas- have to see it to believe it). Join us for a night of amazing sionate” and “having an evil left hand,” On July 15 at 8 p.m., Sound- sounds, as the theremin makes the Smith has performed with a roster of Swap presents Kip Rosser: There’s a jump from the radio to our stage.