Crabbe by Alfred Ainger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Essays of Elia

KU ScholarWorks | The University of Kansas Pre-1923 Dissertations and Theses Collection http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu The Essays of Elia by Helen Beach Smith January, 1909 Submitted to the Department of English of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts This work was digitized by the Scholarly Communications program staff in the KU Libraries’ Center for Digital Scholarship. Master Thesis Smith,Helen Beach 1909 The"Essays of Elia". The "Essays of Elia.tt Thesis presented to the department of* English Literature of the University of Kansas, for the degree of Master of Arts, January, 1909. Helen Beach Smith, BIBLIOGRAPHY. Lamb, Charles. "Works," ed. by William Macdonald. Vol. I. New York, E. P. Button & Co., 1903. Lamb, Charles and Mary. "Works," ed. by E. V. Lucas. Vol. II. London, Methuen & Co., 1903. Ainger, Alfred. "Life of Charles Lamb," in "English Men of Letters" Series. New York, Harper Bros., 188?. Dobell, Bertram. "Sidelights on Charles Lamb." Lucas, E. V. "Life of Charles Lamb," Vol. I. London, Methuen & Co. Adams, W. H. "Lamb's Essays of Ella," in Famous Books. BIBLIOGRAPHY, (continued.) Cornwall, Barry. "Charles Lamb, a Memoir." London, Edward Moxon ft Co., 1806. Rhys, Ernest. introduction in "Essays of Elia." London, Walter Scott ed. and pub. INDEX,, Introduction pp. 1- 3 Chief Characteristics of Lamb pp. 3- 6 His Family pp. 6-8 Tho Personal in his Essays • PP* 8-10 List of the "Essays of Elia" pp. 10-11 Publication of the Essays PP» 11-1? Discussion of the "Essays of Elia" PP. -

A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library

A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library DEBORAH K. HEDGECOCK THE CHARLES LAMB SOCIETY 1995 A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library Copyright Deborah Hedgecock 1995 All rights reserved The Charles Lamb Society 1a Royston Road Richmond Surrey TW10 6LT Registered Charity number 803222: a company limited by guarantee ISSN 0308-0951 Printed by the Stanhope Press, London NW5 (071 387 0041) A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library Contents Preface and Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 4 Information on Guildhall Library 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Printed Books 6 2.1 Access conditions 6 2.2 Charles Lamb Society Collection: Printed Books 7 2.2.1 The CLS Pamphlet and Large Pamphlet Collection 8 2.2.2 The CLS Lecture Collection 8 2.2.3 Charles Lamb Society Publications 8 2.2.3.1 Charles Lamb Bulletins 8 2.2.3.2 Indexes to Bulletin 9 2.2.3.3 List of supplements to Bulletin 9 2.2.3.4 Charles Lamb Society Annual Reports and Financial Statements 9 3. Manuscripts 9 3.1 Access conditions 9 3.2.1 18th- and 19th-century autograph letters and manuscripts 10 3.2.2 Facsimiles and reproductions of Lamb's letters 18 3.2.3 20th-century Individuals and Collections 20 3.2.4 The Elian (Society) 25 3.2.5 The Charles Lamb Society Archive 26 4. Prints, Maps and drawings 35 4.1 Access Conditions 35 4.2.1 Framed Pictures 36 4.2.2 Pictures and Ephemera Collection 37 4.2.3 Collections of Pictures 58 4.2.4 Ephemera Cuttings Collection 59 4.2.5 Maps 61 4.2.6 Printing Blocks 61 4.2.7 Glass Slides 61 5. -

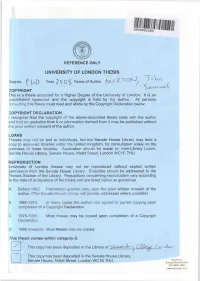

UNIVERSITY of LONDON THESIS Degree

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS T.U, Degree ^ | / \ f ) Year20 0$ Name of Author (KVV\ COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London, It is an jnpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting this thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962-1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975-1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Full Journal

BRIGHAM YOUNG university BULLETIN righambigham a ling university STUDIES AUTUMN 1962 bribrabrigham young s ideal society the kingdom of god 1 keith melville crabbe clutterbuck and co marion B brady the real thing in james s the real thing kenneth bernard proper names in plays by chance or design M C golightly mormon bibliography 1962 allied strategy in world war II11 the churchill era 194219431942 1943 de lamar jensen brigham rrr r young STU DILS university rudiesdies volumestiV number I1 CONTENTS brigham young s ideal society the kingdom of god keith melville 3 crabbe clutterbuck and co marion B brady 19 the real thing in james s the real thing kenneth bernard 31 proper names in plays by chance or design M C golightly 33 mormon bibliography 1962 45 allied strategy in world war II11 the churchill era 194219431942 1943 de lamar jensen 49 university editor ernest L olson managing editor clinton F larson associate managing editor dean B farnsfarnsworthEarnsworth editorial board for 196219631962 1963 1 roman andrus jayfayinyhay V beck lars G crandall dean B farnsworth crawford gates bertrand F harrison charles 1 hart clinton F larson melvin B mabeymahey keith R oakes ernest L olson blaineblamebiame R porter robertrohertroberr K thomas arthur R watkwatkinsms dale H west the purpose of brigham young university studies is to be a voice for the community of LDS scholars brigham young university studies is published by brigham young uni- verversitysity send manuscripts to editor brigham young university studies box 12 mckay building brigham young -

Miller Collection Thurso Main Title Personal Author Date BRN Handbook of the History of Philosophy / by Dr

Miller Collection Thurso Main Title Personal Author Date BRN Handbook of the History of Philosophy / by Dr. Albert Schwegler and Translated and annotatedSchwegler, by Friedrich James Hutchinson Carl Albert; Stirling. Stirling, James Hutchison, 1820-19091888 1651588 An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations / by Adam Smith. Smith, Adam, 1723-1790; McCulloch, J. R. (John Ramsay), 1789-18641850 1651587 Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, Vol. 1 / by John Wright and Edited by James E.Bright, Thorold John, Rogers. Right Hon; Rogers, James E. Thorold (James Edwin1869 Thorold),1651586 1823-1890 Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, Vol. 2 / by John Wright and Edited by James E.Bright, Thorold John, Rogers. Right Hon; Rogers, James E. Thorold (James Edwin1869 Thorold),1651585 1823-1890 John Knox / by W.M. Taylor. Taylor, William M. (William Mackergo), 1829-1895; Knox, John,1884 ca. 1514-15721651584 Italian Pictures, drawn with pen and pencil / by Samuel Manning. Manning, Samuel, LL.D.; Green, Samuel Gosnell 1885 1651583 Morag: a tale of Highland life / by Mrs. Milne Rae. Rae, Milne, Mrs 1872 1650801 The Crossing / by Winston Churchill, with illustrations by Sydney Adamson and Lillian Bayliss.Churchill, Winston, 1871-1947 1924 1650800 Memoir of the Rev. Henry Martyn / by John Sargent. Sargent, John, Rector of Lavington 1820 1650799 Life of the late John Duncan, LL.D. [With a portrait.] / by David Brown. Brown, David, Principal of the Free Church College, Aberdeen 1872 1650798 On Teaching: its ends and means / by Henry Calderwood. Calderwood, Henry, L.L.D., F.R.S.E. 1881 1650797 Indian Polity: a view of the system of administration in India. -

Thomas Carlyle

presented to Gbe Xibrarip of tbe Xflniveraitp of Toronto b£ Bertram 1H. ©avis from tbe boo&e of tbe late Xtonel Davis, 1k.<L 5BOUND ' THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/thomascarlylOOnich r / ENGLISH 3VLEN OF LETTERS EDITED Br JOHN MORLEY THOMAS CA^LTLE MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO O ENGLISH £MEN OF LETTERS THOMAS CARLYLE BY JOHN NICHOL s sa A-**- LONDON : MACMILLAN fcf CO., LIMITED NINETEEN HUNDRED AND NINE First published 1892 Reprinted 1894, 1901, May ana'October 1902, 1904, 1905, 1909 PREFATORY NOTE The following record of the leading events of Carlyle's life and attempt to estimate his genius rely on frequently renewed study of his work, on slight personal impressions — " vidi tantum "—and on information supplied by previous narrators. Of these the great author's chosen literary legatee is the most eminent and, in the main, the most reliable. Every critic of Carlyle must admit as constant obligations to Mr. Froude as every critic of Byron to Moore or of Scott to Lockhart. The works of these masters in biography remain the ample storehouses from which every student will continue to draw. Each has, in a sense, made his subject his own, and each has been similarly arraigned. I must here be allowed to express a feeling akin to indig- nation at the persistent, often virulent, attacks directed against a loyal friend, betrayed, it may be, by excess of faith and the defective reticence that often belongs to genius, to publish too much about his hero. -

The Peal Collection: an Overview

The Kentucky Review Volume 4 Number 1 This issue is devoted to a catalog of an Article 3 exhibition from the W. Hugh Peal Collection in the University of Kentucky Libraries. 1982 The eP al Collection: An Overview John Clubbe University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Clubbe, John (1982) "The eP al Collection: An Overview," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Peal Collection: An Overview John Clubbe During the past two decades W. Hugh Peal, Class of 1922 and one of the university's first Rhodes Scholars, has given to the University of Kentucky Library many of the valuable books and manuscripts he has acquired in over half a century of collecting. In October 1981 the great bulk of his magnificent collection arrived on campus, and for the past year the library staff has been processing it. The seminar held in the King Library on 15 October 1982 is intended to celebrate both this extraordinary gift and the man who made it. -

NEWSLETTER by an Omniscient Narrator

BLEAK HOUSE DICKENS AND LONDON BRISTOL AND CLIFTON DICKENS SOCIETY Book Group Book for 2011 - 2012 An exhibition Bleak House was initially published in twenty monthly instalments between March 1852 and September 1853. It is held by many to be one of Dickens's finest The Museum of London (150 novels, containing a vast, complex and engaging array of minor characters and London Wall, EC2Y 5HN) is sub-plots. The story is told partly by the heroine, Esther Summerson, and partly holding an exhibition - Dickens NEWSLETTER by an omniscient narrator. Memorable characters and London - from 9th include the menacing lawyer Tulkinghorn, the SEPTEMBER 2011 December 2011 to 10th June friendly, but depressive John Jarndyce, and the childish and disingenuous Harold Skimpole, as 2012. well as the likeable but imprudent Richard THE CANTERBURY MINI-CONFERENCE Carstone. It aims to "recreate the atmosphere of Victorian At the end of July, the Canterbury Branch of the Fellowship held a most successful mini-conference for the benefit At the novel's core is a long-running litigation in London.... Paintings, of those who would have been unable to go to Christchurch, New Zealand. But we all know what happened in The Court of Chancery, Jarndyce and Jarndyce, photographs, costume and Christchurch. Which meant, of course, that the AGM took place in Canterbury instead. which has, over time, proved so complicated and objects will illustrate themes expensive to pursue, that it has become the Dickens wove into his works Pat and Morys Cemlyn Jones, Pamela Martin and I attended from our Branch. We stayed in the Canterbury object of hilarity and derision among the Court such as poverty and Cathedral Lodge, a hotel/conference centre within the precincts of the Cathedral itself. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION 1 The children of ]ohn and Elizabeth Lamb were children as wel1.of the Inner Temple, the medieval headquarters of the Knights Templars and Knights of St. ]ohn of ]erusalem and the seat of English law and Inn of Court where once functioned Sir Edward Coke and ]ohn Selden and even Chaucer and Gower some say. From its garden in Shakespeare's vision came the emblems for the Wars of the Roses. Lamb was bom in a ground-ftoor apartment at 2 Crown Office Row on February 10, 1775, and Mary presumably at another address on December 3, 1764. Their brother ]ohn, the ]ames Elia of Elia's "My Relations," pretentious, dogmatic, remotely humane, was bom on ]une 5, 1763. He attended Christ's Hospital from 1769 to 1778, then entered the South Sea House, and there rose from clerk to accountant. He published a pamphlet on the prevention of cruelty to animals, was married, and accumulated a collection of paintings of value. He died on October 26 and was buried at the church of St. Martin Outwich on November 7, 1821. Elizabeth, bom on ]anuary 9, 1762, Samuel, baptized on December 13, 1765, a second Elizabeth, bom on August 30, 1768, Edward, bom on September 3, 1770, and possibly the William interred from the Temple in June 1772 at the church of St. Dunstan-in-the-W est were their sisters and brothers who died in childhood. Elizabeth, the children's mother, was bom in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, in a year not determined. Her father, Edward Field, eamed his living as a gardener and died in 1766. -

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Room Finding Aid

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Room Finding Aid Compiled by Cassie Brand, Melanie Griffin, Peter Libero, and Patrick Smith Not including Fiction other materials shelved in RB stacks. * Item has been entered into the catalog. A/I/1 Sweetser, Moses Foster. King’s handbook of Boston harbor. Cambridge, Mass: M. King, [c1882]. Euripides. The Plays of Euripides. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, [1934]. 2 Volumes. Sophocles. The dramas of Sophocles rendered in English verse, dramatic & lyric. London: J.M. Dent & Co, [1906]. Scott, Sir Walter. The Betrothed, The Highland Widow, and Other Tales. London, Toronto: J. M. Dent; New York: E. P. Dutton, [1921]. Kalevala. Kalevala, the land of heroes. London & Toront: J. M. Dent & sons; New York: E. P. Dutton & Co, [1923-1925]. 2 Volumes. Valmiki. The Ramayana, and the Mahabharata. London: J.M Dent & Sons; New York: E. P. Dutton, [1910]. Gibbon, Edward. Autobiography [of] Edward Gibbon. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, [1932]. Malthus, Thomas Robert. An Essay on Population. London: J. M. Dent & sons, [1933]. Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The House of the Dead. London: J.M. Dent & Sons; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., [1933]. Guthrie, William D. The League of Nations and Miscellaneous Addresses. New York: Columbia University Press, 1923. Reid, Whitelaw. American and English Studies. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1913. 2 Volumes. Stephen, James Fitzjames. Essays by a barrister. London: Smith, Elder and co., 1862. Wallace, H. B. Art and Scenery in Europe, with other papers; being chiefly fragments from the port-folio of the late Horace Binney Wallace, Esquire, of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: J. B. -

Copyrighted Material

I Revolution (1789–1798) The ‘Revolution Controversy’ The books, pamphlets, and essays written in response, pro and con, to the French Revolution constitute a vehement battle of ideas now called the ‘Revolution Controversy’.1 Leading supporters of the French Revolution were Thomas Paine, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft. Principle oppo- nents included Edmund Burke, William Windham, Arthur Young, and, through the succession of The Anti‐Jacobin, George Canning, William Gifford, and John Gifford. These alliances crossed party boundaries between Whigs and Tories; or, rather, the shifting alliances caused factional party divisions. After using his influence in the Whig party to rally support of the American Revolutionaries and Catholic emancipation, Burke surprised many of his constituency when he opposed the French Revolution. He thus became a leader of a conservative fac- tion within the Whig Party. The repudiation of the events in France was articu- lated by Burke in Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790). Burke defended the rights of the landed gentry, who saw much to be risked and nothing to be gained in the overthrow of the existing monarchy. Burke represented a strong constituency, but nevertheless only a fraction of a large populace lacking prop- erty and therefore lacking voting rights as well. With Burke representing the ‘Old Whigs’, Charles James Fox was called upon as spokesperson for the pro‐ revolution ‘New Whigs’. As the violence increased, more of the pro‐revolution faction switched sides. A turning point came early in 1793 with the British declaration of war against France. The first printing of Paine’s Rights of Man (13 March 1791) quickly sold out. -

Marlborough Rare Books Spring Miscellany

MARLBOROUGH RARE BOOKS 1 ST CLEMENT’S COURT LONDON EC4N 7HB TEL. +44 (0) 20 7337 2223 E - MAIL [email protected] A PRIL , 2 0 1 7 L IST 6 1 SPRING MISCELLANY TYPOGRAPHIC CURIOSITY 1 [ADAMS & KING, Publishers]. THE HISTORIE OF EALD STREET, Now called Old Street, With Memoranda of the Parish of St. Luke, and of the Chartreuse. [London]: Adams & King, Printers, Goswell St., [n.d., c. 1855]. £ 500 FIRST EDITION? 8vo, pp. [3] title page & dedication, [12] printed on recto only, [1] advertisement; all printed in various shades of green, blue, yellow, red and black within highly decorative typographic borders; bound in publisher’s red pebble-grained cloth, blocked in blind and gilt, rebacked, a little soiled and worn, but still an appealing copy. An unusual and enchanting specimen piece issued by Adams & King, a long-established firm of London printers. In their preface they state that the work is designed ‘to give our friends some knowledge of the varieties of Type and also showing how differently the same Type may be made to appear. The Borders round the text are also made of many thousands of small pieces of Type variously combined’. These borders which vary from page to page are printed in a variety of colours and make a quite remarkable display of contemporary ornament. The text itself is not without some merit as, apart from the “Historie” it also contains a short account of the career of Joseph Jackson, the important English type founder, who was born in the parish of St Luke and, according to this work, was the first child baptised in St.