Cadence Magazine April – May – June, 2008 Laszlo Gardony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

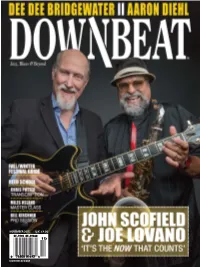

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

David Liebman Papers and Sound Recordings BCA-041 Finding Aid Prepared by Amanda Axel

David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Finding aid prepared by Amanda Axel This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 30, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Berklee Archives Berklee College of Music 1140 Boylston St Boston, MA, 02215 617-747-8001 David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Scores and Charts................................................................................................................................... -

International Jazz News Festival Reviews Concert

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC INTERNATIONAL JAZZ NEWS TOP 10 ALBUMS - CADENCE CRITIC'S PICKS, 2019 TOP 10 CONCERTS - PHILADEPLHIA, 2019 FESTIVAL REVIEWS CONCERT REVIEWS CHARLIE BALLANTINE JAZZ STORIES ED SCHULLER INTERVIEWS FRED FRITH TED VINING PAUL JACKSON COLUMNS BOOK LOOK NEW ISSUES - REISSUES PAPATAMUS - CD Reviews OBITURARIES Volume 46 Number 1 Jan Feb Mar Edition 2020 CADENCE Mainstream Extensions; Music from a Passionate Time; How’s the Horn Treating You?; Untying the Standard. Cadence CD’s are available through Cadence. JOEL PRESS His robust and burnished tone is as warm as the man....simply, one of the meanest tickets in town. “ — Katie Bull, The New York City Jazz Record, December 10, 2013 PREZERVATION Clockwise from left: Live at Small’s; JP Soprano Sax/Michael Kanan Piano; JP Quartet; Return to the Apple; First Set at Small‘s. Prezervation CD’s: Contact [email protected] WWW.JOELPRESS.COM Harbinger Records scores THREE OF THE TEN BEST in the Cadence Top Ten Critics’ Poll Albums of 2019! Let’s Go In Sissle and Blake Sing Shuffl e Along of 1950 to a Picture Show Shuffl e Along “This material that is nearly “A 32-page liner booklet GRAMMY AWARD WINNER 100 years old is excellent. If you with printed lyrics and have any interest in American wonderful photos are included. musical theater, get these discs Wonderfully done.” and settle down for an afternoon —Cadence of good listening and reading.”—Cadence More great jazz and vocal artists on Harbinger Records... Barbara Carroll, Eric Comstock, Spiros Exaras, -

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Finding Aid Prepared by Audrey Abrams, Simmons GSLIS Intern

Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Finding aid prepared by Audrey Abrams, Simmons GSLIS intern This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit July 31, 2014 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Berklee College Archives 2014/02/11 1140 Boylston St Boston, MA, 02215 617-747-8001 Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Historical note................................................................................................................................................4 Scope and contents........................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................4 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 - Page 2 - Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Summary Information Repository Berklee College Archives Creator Berklee College -

Sebastián Cruz Trío

Foto: Mónica Sánchez Mónica Foto: SEBASTIÁN CRUZ TRÍO jazz (Colombia / Estados Unidos) Martes 2 de abril de 2019 · 6:30 p.m. Montería, Auditorio San Jerónimo de la Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana de Montería PULEP: IJD649 Miércoles 3 de abril de 2019 · 7:00 p.m. Sincelejo, Salón de reuniones Parque Comercial Guacarí PULEP: LBX919 Jueves 4 de abril de 2019 · 7:00 p.m. Cartagena, Cetro de Formación para la Cooperación Española PULEP: XXS878 Domingo 7 de abril de 2019 · 11:00 a.m. Bogotá, Sala de Conciertos de la Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango PULEP: FBK975 MÚSICA Y MÚSICOS DE LATINOAMÉRICA Y DEL MUNDO Temporada Nacional de Conciertos Banco de la República 2019 TOME NOTA Los conciertos iniciarán exactamente a la hora indicada en los avisos de prensa y en el programa de mano. Llegar con media hora de antelación le permitirá ingresar al concierto con tranquilidad y disfrutarlo en su totalidad. Si al momento de llegar al concierto éste ya ha iniciado, el personal del auditorio le indicará el momento adecuado para ingresar a la sala de acuerdo con las recomendaciones dadas por los artistas que están en escena. Tenga en cuenta que en algunos conciertos, debido al programa y a los requerimientos de los artistas, no estará permitido el ingreso a la sala una vez el concierto haya iniciado. Agradecemos se abstenga de consumir comidas y bebidas, o fumar durante el concierto con el fin de garantizar un ambiente adecuado tanto para el público como para los artistas. Un ambiente silencioso es propicio para disfrutar la música. Durante el transcurso del concierto, por favor mantenga apagados sus equipos electrónicos, incluyendo teléfonos celulares, buscapersonas y alarmas de reloj. -

Edith Toth Manager

& the Edith Toth Manager TEL (857) 869-6988 FAX (617) 247-8537 WEB [email protected] www.lgjazz.com ADDRESS P.O. BOX 990814 Boston, MA 02199 LASZLO GARDONY is an acclaimed artist who has performed for audiences in 25 countries and has released ten albums. Dave Brubeck called him a “great pianist” and JazzTimes “a formidable improviser who lives in the moment.” He is a graduate of the Bela Bartok Conservatory, the ELTE Science University (in his native Hungary) and Berklee College of Music. In 1987, Gardony won first prize at the Great American Jazz Piano Competition. A long-time professor of Piano at Berklee, he leads his trio of ten years: bassist John Lockwood and drummer Yoron Israel, as well as his quartet and sextet. He has performed and recorded with Yoron Israel’s “High Standards,” Matt Glaser’s “Wayfaring Strangers” and toured with David “Fathead” Newman and the Boston Pops. Signed to Sunnyside Records, Laszlo has been recording for over 25 years. He has collaborated with such musicians as Dave Holland and Miroslav Vitous on his early recordings for the Antilles label. Gardony’s most recent album “Clarity” is a critically acclaimed solo piano recording released on Sunnyside Records in 2013. JOHN LOCKWOOD is known as the first-call bassist in New England. He has played with Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, The Fringe and Gary Burton among many others. His recording credits span over 100 albums. Currently he is Professor at Berklee College of Music, New England Conservatory and at Longy School of Music. He is originally from Cape Town, South Africa. -

Downbeat.Com January 2016 U.K. £3.50

JANUARY 2016 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT LIZZ WRIGHT • CHARLES LLOYD • KIRK KNUFFKE • BEST ALBUMS OF 2015 • JAZZ SCHOOL JANUARY 2016 january 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 1 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ŽanetaÎuntová Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: -

George Benson Charlie Haden Dave Holland William Hooker Jane Monheit Steve Swallow CD Reviews International Jazz News Jazz Stories

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC George Benson Charlie Haden Dave Holland William Hooker Jane Monheit Steve Swallow CD Reviews International jazz news jazz stories Volume 39 Number 4 Oct Nov Dec 2013 More than 50 concerts in venues all around Seattle Keith Jarrett, Gary Peacock, & Jack DeJohnette • Brad Mehldau Charles Lloyd Group w/ Bill Frisell • Dave Douglas Quintet • The Bad Plus Philip Glass • Ken Vandermark • Paal Nilssen-Love • Nicole Mitchell Bill Frisell’s Big Sur Quintet • Wayne Horvitz • Mat Maneri SFJAZZ Collective • John Medeski • Paul Kikuchi • McTuff Cuong Vu • B’shnorkestra • Beth Fleenor Workshop Ensemble Peter Brötzmann • Industrial Revelation and many more... October 1 - November 17, 2013 Buy tickets now at www.earshot.org 206-547-6763 Charles Lloyd photo by Dorothy Darr “Leslie Lewis is all a good jazz singer should be. Her beautiful tone and classy phrasing evoke the sound of the classic jazz singers like Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah aughan.V Leslie Lewis’ vocals are complimented perfectly by her husband, Gerard Hagen ...” JAZZ TIMES MAGAZINE “...the background she brings contains some solid Jazz credentials; among the people she has worked with are the Cleveland Jazz Orchestra, members of the Ellington Orchestra, John Bunch, Britt Woodman, Joe Wilder, Norris Turney, Harry Allen, and Patrice Rushen. Lewis comes across as a mature artist.” CADENCE MAGAZINE “Leslie Lewis & Gerard Hagen in New York” is the latest recording by jazz vocalist Leslie Lewis and her husband pianist Gerard Hagen. While they were in New York to perform at the Lehman College Jazz Festival the opportunity to record presented itself. -

Carol Sloane Marc Cary Gianluigi Trovesi Willie Smith

JULY 2016—ISSUE 171 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM CYRO BAPTISTA PERCUSSION TRAVELER SPECIAL FEATURE HOLLYWOOD JAZZ WILLIE CAROL MARC GIANLUIGI “THE LION” SLOANE CARY TROVESI SMITH Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East JULY 2016—ISSUE 171 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Carol Sloane 6 by andrew vélez [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Marc Cary 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Cyro Baptista 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Gianluigi Trovesi by ken waxman Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : Willie “the lion” Smith 10 by scott yanow [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : Gearbox by eric wendell US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] In Memoriam by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Special Feature : Hollywood Jazz 14 by andrey henkin Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, CD Reviews 16 Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Miscellany 37 Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Contributing Writers Event Calendar 38 Tyran Grillo, George Kanzler, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Wilbur MacKenzie, Mentorship is a powerful thing and can happen with years of collaboration or a single, chance Eric Wendell, Scott Yanow encounter. -

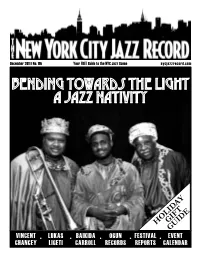

Bending Towards the Light a Jazz Nativity

December 2011 | No. 116 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com bending towards the light a jazz nativity HOLIDAYGIFT GUIDE VINCENT •••••LUKAS BAIKIDA OGUN FESTIVAL EVENT CHANCEY LIGETI CARROLL RECORDS REPORTS CALENDAR The Holiday Season is kind of like a mugger in a dark alley: no one sees it coming and everyone usually ends up disoriented and poorer after the experience is over. 4 New York@Night But it doesn’t have to be all stale fruit cake and transit nightmares. The holidays should be a time of reflection with those you love. And what do you love more Interview: Vincent Chancey than jazz? We can’t think of a single thing...well, maybe your grandmother. But 6 by Anders Griffen bundle her up in some thick scarves and snowproof boots and take her out to see some jazz this month. Artist Feature: Lukas Ligeti As we battle trying to figure out exactly what season it is (Indian Summer? 7 by Gordon Marshall Nuclear Winter? Fall Can Really Hang You Up The Most?) with snowstorms then balmy days, what is not in question is the holiday gift basket of jazz available in On The Cover: A Jazz Nativity our fine metropolis. Celebrating its 26th anniversary is Bending Towards The 9 by Marcia Hillman Light: A Jazz Nativity (On The Cover), a retelling of the biblical story starring jazz musicians like this year’s Three Kings - Houston Person, Maurice Chestnut and Encore: Lest We Forget: Wycliffe Gordon (pictured on our cover) - in a setting good for the whole family.