Gidleigh Common Day Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Devon Rigs Group Sites Table

DEVON RIGS GROUP SITES EAST DEVON DISTRICT and EAST DEVON AONB Site Name Parish Grid Ref Description File Code North Hill Broadhembury ST096063 Hillside track along Upper Greensand scarp ST00NE2 Tolcis Quarry Axminster ST280009 Quarry with section in Lower Lias mudstones and limestones ST20SE1 Hutchins Pit Widworthy ST212003 Chalk resting on Wilmington Sands ST20SW1 Sections in anomalously thick river gravels containing eolian ogical Railway Pit, Hawkchurch Hawkchurch ST326020 ST30SW1 artefacts Estuary cliffs of Exe Breccia. Best displayed section of Permian Breccia Estuary Cliffs, Lympstone Lympstone SX988837 SX98SE2 lithology in East Devon. A good exposure of the mudstone facies of the Exmouth Sandstone and Estuary Cliffs, Sowden Lympstone SX991834 SX98SE3 Mudstone which is seldom seen inland Lake Bridge Brampford Speke SX927978 Type area for Brampford Speke Sandstone SX99NW1 Quarry with Dawlish sandstone and an excellent display of sand dune Sandpit Clyst St.Mary Sowton SX975909 SX99SE1 cross bedding Anchoring Hill Road Cutting Otterton SY088860 Sunken-lane roadside cutting of Otter sandstone. SY08NE1 Exposed deflation surface marking the junction of Budleigh Salterton Uphams Plantation Bicton SY041866 SY0W1 Pebble Beds and Otter Sandstone, with ventifacts A good exposure of Otter Sandstone showing typical sedimentary Dark Lane Budleigh Salterton SY056823 SY08SE1 features as well as eolian sandstone at the base The Maer Exmouth SY008801 Exmouth Mudstone and Sandstone Formation SY08SW1 A good example of the junction between Budleigh -

ITINERARY Day 1 - Saturday, August 15, 2020 Salisbury Arrive at London Heathrow Airport and Be Met by Your Tour Manager

THE MYSTERIES OF ANCIENT BRITAIN AND STONEHENGE – AUGUST 15-24, 2020 In August 2020 Ancient Origins Tours explores the mysteries of Stonehenge and southern Britain with an exclusive 10-day, 9-night tour with special guests Andrew Collins, Graham Phillips and Joanna Gillan. Experience the mysterious ancient sites of southern England including Stonehenge, Avebury, Stanton Drew, as well as the stone circles, megalithic structures and remote landscapes of Devon and Cornwall. Visit also Glastonbury, land of the Holy Grail, and Tintangel, the legendary birthplace of King Arthur. Learn about the sites to be visited as well as the very latest news and theories on Stonehenge and the megalithic builders of ancient Britain with regular guidance and presentations from guests Andrew Collins, Graham Phillips, and Ancient Origins' Joanna Gillan. Take part in meditations where permissible. Dine in some of England’s oldest and most renowned pubs and hotels on this journey of a lifetime. 10 DAYS / 9 NIGHTS - $4550 MEETING PLACE LONDON HEATHROW AIRPORT Pick up point for start of tour is the arrival lounge of any designated terminal at London’s Heathrow Airport. On arrival, all clients will be given transfers to hotel regardless of arrival time or date. At the end of the tour all clients will be brought to Heathrow Airport on the same shared transfer. -- ITINERARY Day 1 - Saturday, August 15, 2020 Salisbury Arrive at London Heathrow Airport and be met by your tour manager. Board your modern motor-coach and travel to Salisbury. Check-in to hotel. Spend the afternoon at leisure. This evening, enjoy an orientation and lecture with special guests. -

Lydford Settlement Profile

r Lydford September 2019 This settlement profile has been prepared by Dartmoor National Park Authority to provide an overview of key information and issues for the settlement. It has been prepared in consultation with Parish/Town Councils and will be updated as necessary. Settlement Profile: Lydford 1 Introduction While set against a village history which is of great significance, the buildings of Lydford are, by and large, late, unremarkable and modest, both in size and architecture. What is remarkable about Lydford is its relative lack of modern development and therefore the preservation of its historic form. Settlement Profile: Lydford 2 Demographics A summary of key population statistics Population 409 Census 2011, determined by best-fit Output Areas Age Profile (Census 2011) Settlement comparison (Census 2011) 100+ Children Working Age Older People 90 Ashburton Buckfastleigh South Brent 80 Horrabridge Yelverton Princetown* 70 Moretonhampstead Chagford 60 S. Zeal & S. Tawton Age Mary Tavy Bittaford 50 Cornwood Dousland Christow 40 Bridford Throwleigh & Gidleigh 30 Sourton Sticklepath Lydford 20 North Brentor Ilsington & Liverton Walkhampton 10 Drewsteignton Hennock 0 Peter Tavy 0 5 10 15 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 Population * Includes prison population Population Settlement Profile: Lydford 3 Housing Stock Average House Prices 2016 Identifying Housing Need Excluding settlements with less than five sales, number of sales labelled following Parishes: Lustleigh 8 Christow 11 Lydford Yelverton 18 Manaton 8 Belstone 6 Chagford 22 Mary Tavy -

South Brent Settlement Profile

South Brent September 2019 This settlement profile has been prepared by Dartmoor National Park Authority to provide an overview of key information and issues for the settlement. It has been prepared in consultation with Parish/Town Councils and will be updated as necessary. Settlement Profile: South Brent 1 Introduction South Brent developed in medieval times, hosting a market and fair. While some industrial activity, linked to cloth mills, supported its economy, its main work was linked with its role as a staging post on the Exeter-Plymouth turnpike road. The village offers a wide range of community services and facilities. Main Shopping Area The main shopping area in South Brent covers Church Street, Fore Street and Station Road. Settlement Profile: South Brent 2 Demographics A summary of key population statistics Population 2,165 Census 2011, defined by best-fit Output Areas Age Profile (Census 2011) Settlement comparison (Census 2011) 100+ Children Working Age Older People Ashburton 90 Buckfastleigh South Brent 80 Horrabridge Yelverton Princetown* 70 Moretonhampstead Chagford 60 S. Zeal & S. Tawton Mary Tavy Age Bittaford 50 Cornwood Dousland Christow 40 Bridford Throwleigh & Gidleigh 30 Sourton Sticklepath Lydford 20 North Brentor Ilsington & Liverton Walkhampton 10 Drewsteignton Hennock 0 Peter Tavy 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 Population * Includes prison population Population Settlement Profile: South Brent 3 Housing Stock Headline data on current housing stock Current Housing Stock Average House Prices -

Higher Uppacott, Medieval Transhumance and the Dartmoor

Higher Uppacott, Medieval Transhumance and the Dartmoor Longhouse The paper explored the reasons for the survival of medieval longhouses in great num- bers on the eastern fringes of Dartmoor. It made great use of Harold Fox’s recently pub- lished research into the medieval development of Dartmoor under royal control and the evidence of transhumance, that is to say the movement of lowland cattle onto the high moor during the summer months. (Dartmoor’s Alluring Uplands: Transhumance and Pastoral Man- agement in the Middle Ages, Harold Fox, published in 2012 by the University of Exeter Press.) He explains how everyone in Devon had the right to pasture their stock on Dartmoor and how the crown sought to control this and make money from it. There were gates which were to be opened on a certain date which had been announced publicly in the major mar- ket towns of the county; how the ancient tenements were established on the moor with free pasturage rights but the obligation that the tenant present himself on horseback for the drifts (when the cattle were counted and appropriate charges levied), how the surrounding parishes had venville rights which meant that they paid a small sum for pasturage Figure 1: Dartmoor Longhouse: Higher Uppacott, Poundsgate, WITM rights but also could, like the tenants of the Ancient Tenements, charge lowlanders to look after their stock, how droveways can be identified throughout Devon and so on. Fox envis- ages a red sea of cattle ebbing and flowing to and from the high moor. He also explains the math’s describing a virtuous circle where all involved made money from this controlled transhumance. -

Free Event Guide

FREE EVENT GUIDE 9 - 24 SEPTEMBER 2017 ”Always enjoyable and inspiring” 2 DEVON OPEN STUDIOS 2017 Welcome to Devon Artist Network’s Open Studios 2017 Members of Devon Artist Network are once again opening their studios and homes across this beautiful county to showcase their work to the public. Devon Artist Network’s mission is to support the county’s artists and crafters by organising events, exhibitions, family workshops and more. Do visit the website www.devonartistnetwork.co.uk where you can access the wealth of talent in Devon and find out how to support it. Charlotte Chance venue 83 We are, as ever, grateful to Helpful Holidays, the West Country holiday cottage specialists, for their support both in enabling us to offer our Emerging Artist Bursaries (see page 3) and in sponsoring part of the administration of the whole event. If you are planning a visit to the West Country this year, why not look at their website www.helpfulholidays.com for a comprehensive selection of beautiful Avenda Burnell Walsh venue 124 holiday cottages across the region. DEVON OPEN STUDIOS 2017 3 How to use this free guide Opening Days and Times Over 250 artists working across the stunning county Unless otherwise stated, venues’ standard opening times are: 11am - 6pm. There are two late evenings (Thursday of Devon are waiting to welcome you to their NORTH DEVON 1 NORTH DEVON 14th and 21st), when some venues open from 6 - 8pm. unique workspaces. There is so much to explore: TORRIDGE && MIDTORRIDGE DEVON If the date is shown the venue is open on those evenings. -

Ash House Throwleigh, Devon Ash House Throwleigh, Devon a Lovely Home Ideally Located on the Edge of a Village and in the Dartmoor National Park

Ash House Throwleigh, Devon Ash House Throwleigh, Devon A lovely home ideally located on the edge of a village and in the Dartmoor National Park. Chagford 3 miles Exeter 20 miles (London Paddington 2 hours) (All distances and times are approximate) Accommodation Kitchen breakfast room| Dining room | Living room Utility room | Music room 4 bedrooms one ensuite | Further study/bedroom Family bathroom Garage | Store Exeter 19 Southernhay East, Exeter EX1 1QD Tel: 01392 423111 [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk Situation Ash House is situated close to the much sought after village of Throwleigh on the northern edge of the Dartmoor National Park adjoining open moorland. The setting of the property, with the direct access onto the moorland is ideal for riding and walking enthusiasts. The property is also readily accessible to the A30 dual carriageway, about four miles away, which gives access to the M5 at Exeter. The A30 dual carriageway is within easy reach, providing easy access to the M5 Motorway, and a mainline train station at Exeter, with regular services to London Paddington in just over 2 hours. The village of Throwleigh has a church, general store/ Post office and village hall and pub with a vibrant community. The attractive stannary town of Chagford lies about three miles to the southeast and has an interesting variety of shops, inns and restaurants, including three Michelin starred Gidleigh Park. There are golf courses at Bovey Castle, Oakhampton and Exeter. The market town of Okehampton, about seven miles away offers a greater variety of shopping and recreational facilities, including a Waitrose supermarket. -

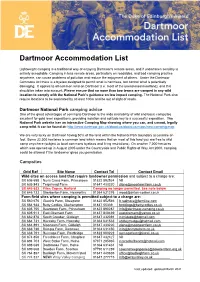

Dartmoor Accommodation List

Dartmoor Accommodation List Lightweight camping is a traditional way of enjoying Dartmoor's remote areas, and if undertaken sensibly is entirely acceptable. Camping in less remote areas, particularly on roadsides, and bad camping practice anywhere, can cause problems of pollution and reduce the enjoyment of others. Under the Dartmoor Commons Act there is a byelaw designed to permit what is harmless, but control what is potentially damaging. It applies to all common land on Dartmoor (i.e. most of the unenclosed moorland), and this should be taken into account. Please ensure that no more than two teams are camped in any wild location to comply with the National Park’s guidance on low impact camping. The National Park also require locations to be separated by at least 100m and be out of sight of roads. Dartmoor National Park camping advice One of the great advantages of coming to Dartmoor is the wide availability of wild and basic campsites excellent for gold level expeditions, providing isolation and solitude key to a successful expedition. The National Park website has an interactive Camping Map showing where you can, and cannot, legally camp wild. It can be found at: http://www.dartmoor.gov.uk/about-us/about-us-maps/new-camping-map We are very lucky on Dartmoor having 50% of the land within the National Park boundary accessible on foot. Some 32,500 hectares is common land which means that on most of this land you are free to wild camp anywhere (subject to local commons byelaws and firing restrictions). On another 7,000 hectares which was opened up in August 2005 under the Countryside and Public Rights of Way Act 2000, camping could be allowed if the landowner gives you permission. -

The Stone Rows of Dartmoor

THE STONE ROWS OF DARTMOOR HERE are on Dartmoor certain rows of stones, each stone wholly unwrought, each set upright in the ground and stand ing free above the surface at a greater or less distance from its Tneighbours on either side. These rows are approximately straight, but curvature and even abrupt changes through a small angle often occur. There is nothing to suggest that such departures from the right line are in any instance purposeful; they may be attributed to faulty work manship or difficulties of alignment on undulating ground. The rows may be either single consisting of but one line of stones, double where two approximately parallel lines have been constructed with an inter vening space of no more than a few feet, or treble consisting of three parallel lines similarly arranged. At one time I would have written, and I think I have written, that there was a sevenfold row on Dartmoor, but a recent precise survey has shown that this is divisible into one single and two treble rows. In the matter of nomenclature these rows have presented a problem; they have been variously named ‘alignments’, ‘avenues’, ‘parallellitha’ and ‘cursi’, no one of which terms meets the need for generality, as absolute in nomenclature as in mathematics; most imply a knowledge of the use and intent of the rows which is certainly mistaken. I have, accordingly, adopted my father’s expedient and used the accurate and noncommittal phrase Stone Rows. His discussion of this matter will be found in his first paper on the subject on page 387 of Vol. -

Prehistoric Henges and Circles

Prehistoric Henges and Circles On 1st April 2015 the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England changed its common name from English Heritage to Historic England. We are now re-branding all our documents. Although this document refers to English Heritage, it is still the Commission's current advice and guidance and will in due course be re-branded as Historic England. Please see our website for up to date contact information, and further advice. We welcome feedback to help improve this document, which will be periodically revised. Please email comments to [email protected] We are the government's expert advisory service for England's historic environment. We give constructive advice to local authorities, owners and the public. We champion historic places helping people to understand, value and care for them, now and for the future. HistoricEngland.org.uk/advice Introductions to Heritage Assets Prehistoric Henges and Circles May 2011 INTRODUCTION In the 3rd and early 2nd millennia BC a remarkable reflecting considerable variation in their size, shape series of circular monuments was built across Britain, and layout. comprising varying combinations of earthwork banks Standing stones, whether single or paired, may be and ditches, timber posts and standing stones. Although better discussed with stone alignments, but they can be archaeologists have traditionally classified these considered here because they are broadly of the same monuments into different categories of henges, stone period, demonstrate the same upright principle, and circles and timber circles, the types cannot always be some are directly associated with stone circles. clearly differentiated and may occur as components of the same site; it seems to be their shared circular form Distributions of stone circles and henges are largely that is most significant. -

And Other Tish Stone Mon Umen Ts

AND OT HE R T ISH ST O N E MON UM E N T S Astro n o mica lly Co n side red L KYE R R S SIR N OR M AN C F . O . P , . DIRECTO R O F THE SOLAR PHYSICS O BSER V ATORY N . G L AS G O\V N S B G S HO LL D , ; HO . C . D . , CA M RID E ; CORRESPONDENT OF THE IN TITUTE OF FRA NCE ; CORRESPONDIN G M EM B ER OF THE I M PERIAL ACADE M Y OF SCIENCES B OF ST . PETERS URG ; THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRO M OTION OF NATIONAL INDUSTRY ; S G T G ; K OF FRANCE THE ROYAL ACADEM Y OF CIENCE , O TIN EN THE FRAN LIN NS ; S B SS I TITUTE , PHILADELPHIA THE ROYAL M EDICAL OCIETY OF RU ELS ; SOCIETY OF ITALIAN SPE CT ROSC OI’ IST S ; THE ROYAL ACADE MY OF PALER M O ; THE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY OF G ENEV A ; OF THE ASTRONOM ICAL X B L Y NC E I T M ; M M R T R AL A AD M , SOCIE Y OF E ICO E E OF HE OYS C E Y OF RO M E AND THE A M ERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL OCIETY , PHILADELPHIA ; HONORARY M E M B ER OF THE ACADE MY OF NATURAL SCIENCE OF CATANIA ; PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY OF YOR K ; LITERARY AND PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY OF M ANCHESTER ; ROYAL CORN W ALL POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTION AND LEI-I IG H UNI V ERSITY iLo n D un M A M L L A N A N D L u C O . -

The Dartmoor Stone Circles

THE DARTMOOR STONE CIRCLES STONE CIRCLE, in western archaeology, is to be distinguished from the hut-circle, which is the foundation of a dwelling, and the retaining circle, which is an adjunct of the grave, associated Awith the cairn or barrow (see pp. 182-191). The purpose of the hut-circle is fully understood, and the associations of the retaining circle are known, but not its ritual intent, if any. The stone circle, according to our terminology, is larger than either the hut or any but a few of the retaining circles, unfitted by structure for use as a habitation, unassociated, as far as can be ascertained, with graves. There is some evidence that large fires were lit within the stone circles, but no evidence as to the purpose of those fires. To avoid all suggestion of knowledge which is not ours, we have taken the trivial name ‘stone circle’, and applied it as a specific name to those circles of stone which are neither huts, retaining circles, nor pounds. Characteristic examples are the circles at Brisworthy (T.D.A., Vol. 35, p. 99), Buttern Hill, Scorhill, and Sherberton, and the ‘Grey Wethers’. Others survive at Whitemoor, Fernworthy, Down Ridge, Merrivale, and Langstone Moor. SCORHILL CIRCLE Scorhill circle has long been known, and often described, but, as often happens, the descriptions have gathered more each from the other than has always accorded with accuracy, and where they have not borrowed they are inconsistent. As far as I know the circle has never been carefully planned and the plan published, an omission the more surprising in that it has been fully recognized as one of our prin cipal Dartmoor monuments, indeed, most writers have agreed with Rowe in the importance which they have attributed to it.