2019 SOTEAG Seabird Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

Shetland Islands, United Kingdom

Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery. 2018, 2(2): 224-227 © 2018 GCdataPR DOI:10.3974/geodp.2018.02.18 Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository www.geodoi.ac.cn Global Change Data Encyclopedia Shetland Islands, United Kingdom Liu, C.* Shi, R. X. Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Keywords: Shetland Islands; Scotland; United Kingdom; Atlantic Ocean; data encyclopedia The Shetland Islands of Scotland is located from 59°30′24″N to 60°51′39″N, from 0°43′25″W to 2°7′3″W, between the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean (Figure 1, Figure 2). Shetland Islands extend 157 km from the northernmost Out Stack Isle to the southernmost Fair Isle. The Islands are 300 km to the west coast of Norway in its east, 291 km to the Faroe Islands in its northwest and 43 km to the North Ronaldsay in its southwest[1–2]. The Main- land is the main island in the Shetland Islands, and 168 km to the Scotland in its south. The Shetland Islands are consisted of 1,018 islands and islets, in which the area of each island or islet is more than 6 m2. The total area of the Shetland Islands is 1,491.33 km2, and the coastline is 2,060.13 km long[1]. There are only 23 islands with each area more than 1 km2 in the Shetland Islands (Table 1), account- ing for 2% of the total number of islands and 98.67% of the total area of the islands. -

Northmavine the Laird’S Room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson

Northmavine The Laird’s room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson Tangwick Haa All aspects of life in Northmavine over the years are Northmavine The wilds of the North well illustrated in the displays at Tangwick Haa Museum at Eshaness. The Haa was built in the late 17th century for the Cheyne family, lairds of the Tangwick Estate and elsewhere in Shetland. Some Useful Information Johnnie Notions Accommodation: VisitShetland, Lerwick, John Williamson of Hamnavoe, known as Tel:01595 693434 Johnnie Notions for his inventive mind, was one of Braewick Caravan Park, Northmavine’s great characters. Though uneducated, Eshaness, Tel 01806 503345 he designed his own inoculation against smallpox, Neighbourhood saving thousands of local people from this 18th Information Point: Tangwick Haa Museum, Eshaness century scourge of Shetland, without losing a single Shops: Hillswick, Ollaberry patient. Fuel: Ollaberry Public Toilets: Hillswick, Ollaberry, Eshaness Tom Anderson Places to Eat: Hillswick, Eshaness Another famous son of Northmavine was Dr Tom Post Offices: Hillswick, Ollaberry Anderson MBE. A prolific composer of fiddle tunes Public Telephones: Sullom, Ollaberry, Leon, and a superb player, he is perhaps best remembered North Roe, Hillswick, Urafirth, for his work in teaching young fiddlers and for his role Eshaness in preserving Shetland’s musical heritage. He was Churches: Sullom, Hillswick, North Roe, awarded an honorary doctorate from Stirling Ollaberry University for his efforts in this field. Doctor: Hillswick, Tel: 01806 503277 Police Station: Brae, Tel: 01806 522381 The camping böd which now stands where Johnnie Notions once lived Contents copyright protected - please contact Shetland Amenity Trust for details. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the contents are accurate, the funding partners do not accept responsibility for any errors in this leaflet. -

The Scandinavian Influence in the Making of Modern Shetland

THE SCANDINAVIAN INFLUENCE IN THE MAKING OF MODERN SHETLAND Hance D. Smith INTRODUCTION The connections between Shetland and Scandinavia generally, and between Shetland and Norway in particular, have constituted the central theme in much scholarship concerned with Shetland over the past century or more. Undoubtedly early interest was spurred by the legacy of Dark Age settlement of the islands from western Norway, a legacy which included a distinctive language, Norn, descended from Old Norse, with associated place-names, folklore and material culture. Further, Shetland lay within the geographical province of the Norse sagas, although it is little mentioned in them. More recently, contacts have been maintained through the fisheries and travel, and most recently of all, through the offshore oil industry. This pre-occupation with things Norwegian in Shetland has been due in part to a natural interest in the historical roots of the 'island way of life', and no doubt owes something also to the shared circumstances of location on the periphery of Europe, possessing similar physical environments of islands, deeply indented coastlines and hilly or mountainous interiors, as well as economies based to a large extent on primary production, notably a combination of fishing and farming. In these Scandinavian-oriented studies relatively little attention has been paid until recently to the period after the transference of the Northern Isles to Scotland in 1468-69, and particularly to the period since the beginning of the eighteenth century, when the processes of modern economic development of the islands gained momentum. These processes have led to substantial differences in development at the regional scale between Orkney and Shetland on the one hand, and the regions of the Scandinavian countries with which they are directly comparable, on the other. -

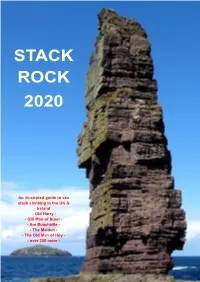

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Cetaceans of Shetland Waters

CETACEANS OF SHETLAND The cetacean fauna (whales, dolphins and porpoises) of the Shetland Islands is one of the richest in the UK. Favoured localities for cetaceans are off headlands and between sounds of islands in inshore areas, or over fishing banks in offshore regions. Since 1980, eighteen species of cetacean have been recorded along the coast or in nearshore waters (within 60 km of the coast). Of these, eight species (29% of the UK cetacean fauna) are either present throughout the year or recorded annually as seasonal visitors. Of recent unusual live sightings, a fin whale was observed off the east coast of Noss on 11th August 1994; a sei whale was seen, along with two minkes whales, off Muckle Skerry, Out Skerries on 27th August 1993; 12-14 sperm whales were seen on 14th July 1998, 14 miles south of Sumburgh Head in the Fair Isle Channel; single belugas were seen on 4th January 1996 in Hoswick Bay and on 18th August 1997 at Lund, Unst; and a striped dolphin came into Tresta Voe on 14th July 1993, eventually stranding, where it was euthanased. CETACEAN SPECIES REGULARLY SIGHTED IN THE REGION Humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae Since 1992, humpback whales have been seen annually off the Shetland coast, with 1-3 individuals per year. The species was exploited during the early part of the century by commercial whaling and became very rare for over half a century. Sightings generally occur between May-September, particularly in June and July, mainly around the southern tip of Shetland. Minke whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata The minke whale is the most commonly sighted whale in Shetland waters. -

Bluemull Sound STAG 1 Report Zettrans June 2008

Bluemull Sound STAG 1 Report ZetTrans June 2008 Prepared by: ............................................... Approved by: ................................................ Andrew Robb Paul Finch Consultant Associate Director Bluemull Sound STAG 1 Report Rev No Comments Date 2 Final following Client Comment 27/06/08 1 Draft for Client Review 21/05/08 Lower Ground Floor, 3 Queens Terrace, Aberdeen, AB10 1XL Telephone: 01224 627800 Fax: 01224 627849 Website: http://www.fabermaunsell.com Job No 55280 TABT/701 Reference Date Created June 2008 This document has been prepared by Faber Maunsell Limited (“Faber Maunsell”) for the sole use of our client (the “Client”) and in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between Faber Maunsell and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by Faber Maunsell, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of Faber Maunsell. f:\projects\55280tabt - zettrans regional transport strategy\workstage 701 - bluemull stag\11\stag 1 report\bluemull sound stag 1 report 250608.doc Executive Summary Introduction Zetland Transport Partnership (ZetTrans) commissioned Faber Maunsell to undertake a Scottish Transport Appraisal Guidance (STAG 1) assessment to examine options for the future of the transport links across Bluemull Sound, connecting the North Isles of Unst, Fetlar and Yell. This Executive Summary summarises the STAG process undertaken in order to determine the study options to be taken forward to STAG 2 Appraisal. Doing nothing is not considered feasible due to the impacts and costs of continuing to operate ageing ferry and terminal infrastructure beyond its lifespan. -

Jindalee, Quarff, Shetland, ZE2 9EY This Attractive, Three Bedroom, Private Family Bungalow Is Situated in an Elevated Area of Hillside, Quarff

Jindalee, Quarff, Shetland, ZE2 9EY This attractive, three bedroom, private family bungalow is situated in an elevated area of Hillside, Quarff. It has been Offers over £225,000 are invited recently refurbished with a modern galley Kitchen and bathroom with all high-spec appliances and conveniences and is in move in Porch, Utility Room, Vestibule, combined condition. Kitchen & Dining Area, Sitting Room, three Accommodation Double Bedrooms (one with WC) and The landscaped, established garden grounds are easy to Bathroom. maintain with mature trees and bushes, grassed areas and raised decking and patio areas for alfresco entertaining. There are the added benefits of two garden sheds, a large polytunnel with Landscaped garden grounds with raised established fruit trees and raised and internal and external raised vegetable beds, established bushes and beds that provide for an array of fresh produce to be produced for External plants, drying green, timber deck, two a self-sufficient lifestyle. timber garden sheds and a large polytunnel with mature fruit trees. The rural area of Quarff itself has a public hall with regular bus services to the south mainland and also to Lerwick (approx. 6 miles away) that has all local amenities, such as, sea front Highly recommended. Please contact the harbour, nurseries, primary and high schools, library, hospital, Viewings Sellers on 01950 477 453 or 07833 755 leisure centre, cinema complex, museum, supermarkets, retail 574 to arrange a viewing. shops, bars and restaurants. Cunningsburgh and Sandwick are further south and provide an alternative choice of schools. Early entry is available once conveyancing Entry formalities permit. This property presents an ideal opportunity for a growing family, those requiring accommodation on one level and budding EPC Rating D(67) gardening enthusiasts. -

The Shetland Isles June 20-27

Down to Earth “Earth science learning for all” The Shetland Isles June 20-27 The coastline of Papa Stour A word from your leaders... At last we are returning to Shetland some four years after our last visit. We have visited Shetland many times over the years, but this is a very different Shetland field trip, with most of the time based in North Mainland, allowing us access to new places, including the amazing coast of Papa Stour, every inch of which is European Heritage Coastline. We are basing most of the trip at the St Magnus Bay Hotel in Hillswick where Andrea and Paul will look after us. By the time of our visit they will have pretty well completed a five year refurbishment of this fine wooden building. Shetland is a very special place, where the UK meets the Nordic lands and it’s geology is pretty special too. It is crossed by the Great Glen fault in a north-south line which brings in slivers of metamorphic rocks from the Lewisian, Moinian and Dalradian. These rocks are overlain by sediments and volcanics from the Devonian. We’ll take in much of the rich variety that make up this Geopark. We’ll have the use of a minibus, with additional cars as required for this trip, which we are both greatly looking forward to. We expect this trip to book up fast, so don’t delay in getting back to us. Chris Darton & Colin Schofield Course Organisers/Leaders [email protected] Getting to Shetland Getting to Shetland is an adventure in itself, and can be part of your ‘Shetland experience’. -

Hascosay Special Area of Conservation (Sac)

HASCOSAY SPECIAL AREA OF CONSERVATION (SAC) CONSERVATION ADVICE PACKAGE Image: Sphagnum moss and round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) © Lorne Gill/NatureScot Site Details Site name: Hascosay Map: https://sitelink.nature.scot/site/8270 Location: Highlands and Islands Site code: UK0019793 Area (ha): 164.19 Date designated: 17 March 2005 Qualifying features Qualifying feature SCM assessed SCM visit date UK overall condition on Conservation this site Status Blanket bog* [H7130] Favourable 2 September 2009 Unfavourable-Bad Maintained Otter (Lutra lutra) [S1355] Unfavourable No 7 June 2012 Favourable change Notes: Assessed condition refers to the condition of the SAC feature assessed at a site level as part of NatureScot’s Site Condition Monitoring (SCM) programme. Conservation status is the overall condition of the feature throughout its range within the UK as reported to the European Commission under Article 17 of the Habitats Directive in 2019. * A Habitats Directive Priority Habitat Overlapping and adjacent Protected Areas Hascosay Special Area of Conservation (SAC) has the same boundary as Hascosay Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) https://sitelink.nature.scot/site/767. Parts of Hascosay SAC are adjacent to parts of Bluemull and Colgrave Sounds Special Protection Area (SPA) https://sitelink.nature.scot/site/10483 and Fetlar SPA https://sitelink.nature.scot/site/8498 Key factors affecting the qualifying features Blanket bog This Habitats Directive Priority Habitat is found in areas of moderate to high rainfall and a low level of evapotranspiration, allowing peat to develop over large expanses of undulating ground. Blanket bogs are considered active when they support a significant area of vegetation that is peat-forming. -

Viewpoint Selection Criteria

VIKING WIND FARM ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT 1 . VIEWPOINT SELECTION CRITERIA 1.1 BACKGROUND In 2006 ASH design + assessment (ASH) undertook preliminary reconnaissance of the study area in order to build up a picture of the existing landscape character, topographical features and historical associations. The site familiarisation exercise also identified, in broad terms, potential visual receptors. Initial consultation with SNH was undertaken and they provided details of eight initial viewpoints. Following continued consultation a further list of potential viewpoints was put forward by ASH and SNH and this final list was agreed with both SNH and Shetland Islands Council in Autumn 2007. 1.2 METHODOLOGY The visual impact assessment of the development was carried out broadly based on the Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Assessment (2nd edition, 2002) and guidelines on current best practice, including: 'Guidelines on the Environmental Impacts of Windfarms & Small Scale Hydroelectric Schemes' (SNH February 2001); ‘Visual Representation of Windfarms, Good Practice Guidance’ SNH 2006; Landscape Character Assessment (The Countryside Agency and SNH 2002); and Visual Assessment of Windfarms: Best Practice (conducted by University of Newcastle for SNH, 2002). A Zone of Theoretical Visibility (ZTV) programme was run for the area in order to ascertain the visual envelope, to guide the field assessment of the impact of the proposals on properties, outdoor spaces and routeways within the envelope. A wide-ranging comprehensive visual assessment was then carried out of all receptors with the potential to receive an impact within the study area, supplemented by visualisations from a subset of points (those considered key viewpoints) as part of this wider assessment. -

Download a Leaflet on Yell from Shetland

Yell The Old Haa Yell Gateway to the northern isles The Old Haa at Burravoe dates from 1672 and was opened as a museum in 1984. It houses a permanent display of material depicting the history of Yell. Outside there is a monument to the airmen who lost their lives in 1942 in a Catalina crash on the moors of Some Useful Information South Yell. Accommodation: VisitShetland, Lerwick The Old Haa is also home to the Bobby Tulloch Tel: 08701 999440 Collection and has rooms dedicated to photographic Ferry Booking Office: Ulsta Tel: 01957 722259 archives and family history. Neighbourhood The museum includes a tearoom, gallery and craft Information Point: Old Haa, Burravoe, Tel 01957 722339 shop, walled garden and picnic area, and is also a Shops: Cullivoe, Mid Yell, Aywick, Burravoe, Neighbourhood Information Point. and Ulsta Fuel: Cullivoe, Mid Yell, Aywick, Ulsta and Bobby Tulloch West Sandwick Bobby Tulloch was one of Yell’s best-known and Public Toilets: Ulsta and Gutcher (Ferry terminals), loved sons. He was a highly accomplished naturalist, Mid Yell and Cullivoe (Piers) photographer, writer, storyteller, boatman, Places to Eat: Gutcher and Mid Yell musician and artist. Bobby was the RSPB’s Shetland Post Offices: Cullivoe, Gutcher, Camb, Mid Yell, representative for many years and in 1994 was Aywick, Burravoe, and Ulsta awarded an MBE for his efforts on behalf of wildlife Public Telephones: Cullivoe, Gutcher, Sellafirth, Basta, and its conservation. He sadly died in 1996 aged 67. Camb, Burravoe, Hamnavoe, Ulsta and West Sandwick Leisure Centre: Mid Yell Tel: 01957 702222 Churches: Cullivoe, Sellafirth, Mid Yell, Otterswick, Burravoe and Hamnavoe Doctor and Health Centre: Mid Yell Tel: 01957 702127 Police Station: Mid Yell Tel: 01957 702012 Contents copyright protected - please contact shetland Amenity Trust for details.