Willa Cather: the Letters and Novels of a Romantic Modernist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corruption of the Characters in Willa Cather's a Lost Lady

Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8435 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.51, 2018 Corruption of the Characters in Willa Cather’s A Lost Lady Dewi Nurnani Puppetry Department, Faculty of Performing Arts, Indonesia Institute of Arts, Surakarta, Central Java, Indonesia, 57126 email: [email protected] Abstract This writing studies about corruption of the characters in the novel entitled A Lost Lady by Willa Cather. The mimetic approach is used to analyze this novel. So in creating art, an author is much influenced by the social condition of society in which he lives or creates, directly or indirectly. It can be learned that progression does not always make people happy but often it brings difficulties and even disaster in their lives. It is also found that the corruption in the new society happens because the characters are unable to endure their passionate nature as well as to adapt with the changing.To anticipate the changing, one must have a strong mentality among other things, by religion or a good education in order that he does not fall into such corruption as the characters in A Lost Lady . Keywords : corruption, ambition, passionate, new values, old values 1. Background of The Study Willa Sibert Cather, an American novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist, and poet, was born on December 7, 1983 near Winchester, Virginia, in the fourth generation of an Anglo-Irish family. Her father, Charles F. Cather, and her mother, Mary Virginia Cather, and also their family moved to the town of red Cloud, Nebraska, when she was nine years old. -

The Making of Willa Cather's One of Ours: the Role of Dorothy Canfield

Janis P. Stout The Making of Willa Cather’s One of Ours: The Role of Dorothy Canfield Fisher n March 12, 1921, when Willa Cather was well into the writing of her novel of male disaffection from Nebraska and rebirth in war, One of Ours, she wrote her firstO letter in five years to her longtime friend and fellow-writer Dorothy Canfield Fisher. Three days later she wrote again, urging that she and Canfield Fisher become reconciled after a long es- trangement. (Sixteen years earlier Dorothy had successfully opposed Cather’s publication of a short story that she believed would be unduly wounding to a friend to whom she had introduced Cather.) In this sec- ond letter Cather mentioned that she felt in need of Canfield Fisher’s help with the novel, stating, indeed, that she was (in the words of Mark J. Madigan’s summary of the correspondence) “the only person who could help her with it” (“Rift” 124)1. Why, one wonders, was Dorothy Canfield Fisher the only person who could provide that help? What could Canfield Fisher provide that no one else could? That is the question I want to take up here. Madigan’s essay on the exchange of letters demonstrates that One of Ours provided a structured ground, delimited by their professionalism, on which the two women could achieve reconciliation. The biographical issues he elucidates, relating to both the causes of their estrangement and the clarifications that led to their reconciliation, are of keen interest, particularly as they afford insight into Cather’s sense of her own provin- cialism. -

Willa Cather and American Arts Communities

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2004 At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jewell, Andrew W., "At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 15. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES by Andrew W. Jewel1 A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Susan J. Rosowski Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2004 DISSERTATION TITLE 1ather and Ameri.can Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewel 1 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Approved Date Susan J. Rosowski Typed Name f7 Signature Kenneth M. Price Typed Name Signature Susan Be1 asco Typed Name Typed Nnme -- Signature Typed Nnme Signature Typed Name GRADUATE COLLEGE AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES Andrew Wade Jewell, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2004 Adviser: Susan J. -

Lawyers in Willa Cather's Fiction, Nebraska Lawyer

Lawyers in Willa Cather’s Fiction: The Good, The Bad and The Really Ugly by Laurie Smith Camp Cather Homestead near Red Cloud NE uch of the world knows Nebraska through the literature of If Nebraska’s preeminent lawyer and legal scholar fared so poorly in Willa Cather.1 Because her characters were often based on Cather’s estimation, what did she think of other members of the bar? Mthe Nebraskans she encountered in her early years,2 her books and stories invite us to see ourselves as others see us— The Good: whether we like it or not. In “A Lost Lady,”4 Judge Pommeroy was a modest and conscientious Roscoe Pound didn’t like it one bit when Cather excoriated him as a lawyer in the mythical town of Sweetwater, Nebraska. Pommeroy pompous bully in an 1894 ”character study” published by the advised his client, Captain Daniel Forrester,5 during Forrester’s University of Nebraska. She said: “He loves to take rather weak- prosperous years, and helped him to meet all his legal and moral minded persons and browbeat them, argue them down, Latin them obligations when the depression of the 1890's closed banks and col- into a corner, and botany them into a shapeless mass.”3 lapsed investments. Pommeroy appealed to the integrity of his clients, guided them by example, and encouraged them to respect Laurie Smith Camp has served as the rights of others. He agonized about the decline of ethical stan- Nebraska’s deputy attorney general dards in the Nebraska legal profession, and advised his own nephew for criminal matters since 1995. -

Web Book Club Sets

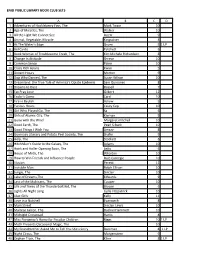

ENID PUBLIC LIBRARY BOOK CLUB SETS A B C D 1 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Mark Twain 10 2 Age of Miracles, The Walker 10 3 All the Light We Cannot See Doerr 9 4 Animal, Vegetable, Miracle Kingsolver 4 5 At The Water's Edge Gruen 5 1 LP 6 Bel Canto Patchett 6 7 Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, The Kim Michele Richardson 8 8 Change in Attitude Shreve 10 9 Common Sense Paine 10 10 Crazy Rich Asians Kwan 5 11 Distant Hours Morton 9 12 Dog Who Danced, The Susan Wilson 10 13 Dreamland: the True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic Sam Quinones 8 14 Dreams to Dust Russell 7 15 Eat Pray Love Gilbert 12 16 Ender's Game Card 10 17 Fire in Beulah Askew 5 18 Furious Hours Casey Cep 10 19 Girl Who Played Go, The Sa 6 20 Girls of Atomic City, The Kiernan 9 21 Gone with the Wind Margaret mitchell 10 22 Good Earth, The Pearl S Buck 10 23 Good Things I Wish You Amsay 8 24 Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, The Shafer 9 25 Help, The Stockett 6 26 Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, The Adams 10 27 Honk and Holler Opening Soon, The Letts 6 28 House of Mirth, The Wharton 10 29 How to Win Friends and Influence People Dale Carnegie 10 30 Illusion Peretti 12 31 Invisible Man Ralph Ellison 10 32 Jungle, The Sinclair 10 33 Lake of Dreams,The Edwards 9 34 Last of the Mohicans, The Cooper 10 35 Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, The Bryson 6 36 Lights All Night Long Lydia Fitzpatrick 10 37 Lilac Girls Kelly 11 38 Love in a Nutshell Evanovich 8 39 Main Street Sinclair Lewis 10 40 Maltese Falcon, The Dashiel Hammett 10 41 Midnight Crossroad Harris 8 -

A Wagner Matinee"

Willa Cather Newsletter & Review Fall2007 Volume LI, No. 2 ll th International Cather Seminar Explores Willa Cather: A Writer’s Worlds Marc Ch6netier makes a point during a speech delivered at the Sorbonne A.S. Byatt responds to Seminar Director Robert Thacker following a paper Nouvelle in Paris. Photograph by Betty Kort. session at the Abbaye St-Michel-de-Frigolet. Photograph by Betty Kort. Keynote addresses by Marc Chrnetier and A. S. Byatt One hundred fifty-one participants traveled to Paris in the highlighted the first Cather International Seminar to be held in latter part of June for the first portion of the seminar and then went France. Chrnetier, who is President of the European Association by train to Provence for the balance of the time in France. Charles of American Studies, has translated eight of Cather’s novels. He A. Peek, Professor of English at the University of Nebraska at is Professor of American Literature at the University of Paris Kearney and president of the Cather Foundation, set a standard 7 and a Senior member of the Institut Universitaire de France. of excellence when he opened the seminar in Paris with a paper Chrnetier spoke at the Sorbonne Nouvelle in Paris, discussing comparing the challenges facing the Cather Foundation today to the difficulties associated with completing translations and the challenges facing Cather’s fiction. A limited number of papers his reactions to the works of Cather. Byatt, who was made a followed at the Sorbonne Nouvelle in Paris, with the bulk of the Dame of the British Empire in 1999 in appreciation for her papers read at the Abbaye St-Michel-de-Ffigolet in Provence. -

Immigration in Nebraska

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Agricultural Leadership, Education & Strategic Discussions for Nebraska Communication Department 2008 Immigration in Nebraska Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sdn "Immigration in Nebraska" (2008). Strategic Discussions for Nebraska. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sdn/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Agricultural Leadership, Education & Communication Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Strategic Discussions for Nebraska by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STRATEGIC DISCUSSIONS FOR nebraska Immigration in Nebraska KFSBOPFQVLCB?O>PH>¨ FK@LIK LIIBDBLC LROK>IFPJ>KA >PPLJJRKF@>QFLKP @HKLTIBADBJBKQP Strategic Discussions for Nebraska is grateful to its funding organization – the Robert and Ardis James Family Foundation in New York. Their financial support and their guidance have made this project possible. Strategic Discussions for Nebraska benefits from the involvement and advice of an external advisory board. We wish to express appreciation to the board members: Jonathan Brand, J.D., President of Doane College in Crete Dr. Eric Brown, General Manager of KRVN Radio in Lexington Dr. Will Norton, Jr., Dean of the UNL College of Journalism and Mass Communications Dr. Frederik Ohles, President of Nebraska Wesleyan University in Lincoln Dr. Janie Park, President of Chadron State College, Chadron -

Willa Cather and the Swedes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Fall 1984 Willa Cather And The Swedes Mona Pers University College at Vasteras Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Pers, Mona, "Willa Cather And The Swedes" (1984). Great Plains Quarterly. 1756. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1756 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WILLA CATHER AND THE SWEDES MONAPERS Willa Cather's immigrant characters, almost a able exaggeration when in 1921 she maintained literary anomaly at the time she created them, that "now all Miss Cather's books have been earned her widespread critical and popular ac translated into the Scandinavian," the Swedish claim, not least in the Scandinavian countries, a translations of 0 Pioneers! and The Song of market she was already eager to explore at the the Lark whetted the Scandinavian appetite beginning of her literary career. Sweden, the for more Cather. As the 1920s drew to a close, first Scandinavian country to "discover" her her reputation grew slowly but steadily. Her books, issued more translations of Cather fic friend George Seibel was probably guilty of tion than any other European country. In considerably less exaggeration than was Eva fact, Sweden was ten years ahead of any other Mahoney when he recalled "mentioning her Scandinavian country in publishing the transla name in the Gyldendal Boghandel in Copen tion of a Cather novel (see table). -

EMPIRICAL TESTS of COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION Christopher Buccafusco† & Paul J

0001-0044_BUCCAFUSCO_081313_WEB (DO NOT DELETE) 8/13/2013 4:50 PM DO BAD THINGS HAPPEN WHEN WORKS ENTER THE PUBLIC DOMAIN?: EMPIRICAL TESTS OF COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION Christopher Buccafusco† & Paul J. Heald †† ABSTRACT According to the current copyright statute, copyrighted works of music, film, and literature will begin to transition into the public domain in 2018. While this will prove a boon for users and creators, it could be disastrous for the owners of these valuable copyrights. Therefore, the next few years will likely witness another round of aggressive lobbying by the film, music, and publishing industries to extend the terms of already-existing works. These industries, and a number of prominent scholars, claim that when works enter the public domain, bad things will happen to them. They worry that works in the public domain will be underused, overused, or tarnished in ways that will undermine the works’ economic and cultural value. Although the validity of their assertions turns on empirically testable hypotheses, very little effort has been made to study them. This Article attempts to fill that gap by studying the market for audiobook recordings of bestselling novels, a multi-million dollar industry. Data from this study, which includes a novel human-subjects experiment, suggest that term-extension proponents’ claims about the public domain are suspect. Audiobooks made from public domain bestsellers (1913–22) are significantly more available than those made from copyrighted bestsellers (1923–32). In addition, the experimental evidence suggests that professionally made recordings of public domain and copyrighted books are of similar quality. Finally, while a low quality recording seems to lower a listener’s valuation of the underlying work, the data do not suggest any correlation between that valuation and the legal status of the underlying work. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscripthas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affectreproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sectionswith small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI .. A Bell & Howell mtorrnauon Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Getting Back to Their Texts: A Reconsideration of the Attitudes of Willa Cather and Hamlin Garland Toward Pioneer Li fe on the Midwestern Agricultural Frontier A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHJLOSOPHY IN ENGLISH AUGUST 1995 By Neil Gustafson Dissertation Committee: Mark K. -

Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory

Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory Edited by William E. Cain Professor of English Wellesley College A Routledge Series 94992-Humphries 1_24.indd 1 1/25/2006 4:42:08 PM Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory William E. Cain, General Editor Vital Contact Negotiating Copyright Downclassing Journeys in American Literature Authorship and the Discourse of from Herman Melville to Richard Wright Literary Property Rights in Patrick Chura Nineteenth-Century America Martin T. Buinicki Cosmopolitan Fictions Ethics, Politics, and Global Change in the “Foreign Bodies” Works of Kazuo Ishiguro, Michael Ondaatje, Trauma, Corporeality, and Textuality in Jamaica Kincaid, and J. M. Coetzee Contemporary American Culture Katherine Stanton Laura Di Prete Outsider Citizens Overheard Voices The Remaking of Postwar Identity in Wright, Address and Subjectivity in Postmodern Beauvoir, and Baldwin American Poetry Sarah Relyea Ann Keniston An Ethics of Becoming Museum Mediations Configurations of Feminine Subjectivity in Jane Reframing Ekphrasis in Contemporary Austen, Charlotte Brontë, and George Eliot American Poetry Sonjeong Cho Barbara K. Fischer Narrative Desire and Historical The Politics of Melancholy from Reparations Spenser to Milton A. S. Byatt, Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie Adam H. Kitzes Tim S. Gauthier Urban Revelations Nihilism and the Sublime Postmodern Images of Ruin in the American City, The (Hi)Story of a Difficult Relationship from 1790–1860 Romanticism to Postmodernism Donald J. McNutt Will Slocombe Postmodernism and Its Others Depression Glass The Fiction of Ishmael Reed, Kathy Acker, Documentary Photography and the Medium and Don DeLillo of the Camera Eye in Charles Reznikoff, Jeffrey Ebbesen George Oppen, and William Carlos Williams Monique Claire Vescia Different Dispatches Journalism in American Modernist Prose Fatal News David T. -

Banned & Challenged Classics

26. Gone with the Wind, 26. Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell by Margaret Mitchell 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright Banned & Banned & 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Challenged Challenged by Ken Kesey by Ken Kesey 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, Classics Classics by Kurt Vonnegut by Kurt Vonnegut 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway by Ernest Hemingway 33. The Call of the Wild, 33. The Call of the Wild, The titles below represent banned or The titles below represent banned or by Jack London by Jack London challenged books on the Radcliffe challenged books on the Radcliffe 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of by James Baldwin by James Baldwin the 20th Century list: the 20th Century list: 38. All the King's Men, 38. All the King's Men, 1. The Great Gatsby, 1. The Great Gatsby, by Robert Penn Warren by Robert Penn Warren by F. Scott Fitzgerald by F. Scott Fitzgerald 40. The Lord of the Rings, 40. The Lord of the Rings, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.D. Salinger by J.D. Salinger 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 3. The Grapes of Wrath, 3.