The Touch of Color PASTELS at the NATIONAL GALLERY of ART

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Planner Guide 2020 Contents

EVENT PLANNER GUIDE 2020 CONTENTS WELCOME TEAM BUILDING 17 TRANSPORT 46 TO LONDON 4 – Getting around London 48 – How we can help 5 SECTOR INSIGHTS 19 – Elizabeth Line 50 – London at a glance 6 – Tech London 20 – Tube map 54 – Financial London 21 – Creative London 22 DISCOVER – Medical London 23 YOUR LONDON 8 – Urban London 24 – New London 9 – Luxury London 10 – Royal London 11 PARTNER INDEX 26 – Sustainable London 12 – Cultural London 14 THE TOWER ROOM 44 – Leafy Greater London 15 – Value London 16 Opening its doors after an impressive renovation... This urban sanctuary, situated in the heart of Mayfair, offers 307 contemporary rooms and suites, luxurious amenities and exquisite drinking and dining options overseen by Michelin-starred chef, Jason Atherton. Four flexible meeting spaces, including a Ballroom with capacity up to 700, offer a stunning setting for any event, from intimate meetings to banquet-style 2 Event Planner Guide 2020 3 thebiltmoremayfair.com parties and weddings. WELCOME TO LONDON Thanks for taking the time to consider London for your next event. Whether you’re looking for a new high-tech So why not bring your delegates to the capital space or a historic building with more than and let them enjoy all that we have to offer. How we can help Stay connected Register for updates As London’s official convention conventionbureau.london conventionbureau.london/register: 2,000 years of history, we’re delighted to bureau, we’re here to help you conventionbureau@ find out what’s happening in introduce you to the best hotels and venues, Please use this Event Planner Guide as a create a world-class experience for londonandpartners.com London with our monthly event as well as the DMCs who can help you achieve practical index and inspiration – and contact your delegates. -

Tate Report 2010-11: List of Tate Archive Accessions

Tate Report 10–11 Tate Tate Report 10 –11 It is the exceptional generosity and vision If you would like to find out more about Published 2011 by of individuals, corporations and numerous how you can become involved and help order of the Tate Trustees by Tate private foundations and public-sector bodies support Tate, please contact us at: Publishing, a division of Tate Enterprises that has helped Tate to become what it is Ltd, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG today and enabled us to: Development Office www.tate.org.uk/publishing Tate Offer innovative, landmark exhibitions Millbank © Tate 2011 and Collection displays London SW1P 4RG ISBN 978-1-84976-044-7 Tel +44 (0)20 7887 4900 Develop imaginative learning programmes Fax +44 (0)20 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Strengthen and extend the range of our American Patrons of Tate Collection, and conserve and care for it Every effort has been made to locate the 520 West 27 Street Unit 404 copyright owners of images included in New York, NY 10001 Advance innovative scholarship and research this report and to meet their requirements. USA The publishers apologise for any Tel +1 212 643 2818 Ensure that our galleries are accessible and omissions, which they will be pleased Fax +1 212 643 1001 continue to meet the needs of our visitors. to rectify at the earliest opportunity. Or visit us at Produced, written and edited by www.tate.org.uk/support Helen Beeckmans, Oliver Bennett, Lee Cheshire, Ruth Findlay, Masina Frost, Tate Directors serving in 2010-11 Celeste -

Curating Queer British Art, 1861-1967 at Tate Britain and Being Human at Wellcome Collection, London

Rejecting Normal: Curating Queer British Art, 1861-1967 at Tate Britain and Being Human at Wellcome Collection, London Clare Barlow Independent curator This item has been published in Issue 01 ‘Transitory Parerga: Access and Inclusion in Contemporary Art,’ edited by Vlad Strukov. To cite this item: Barlow С (2020) Rejecting normal: Curating Queer British Art, 1861-1967 at Tate Britain and Being Human at Wellcome Collection, London. The Garage Journal: Studies in Art, Museums & Culture, 01: 264-280. DOI: 10.35074/GJ.2020.1.1.016 To link to this item: https://doi.org/10.35074/GJ.2020.1.1.016 Published: 30 November 2020 ISSN-2633-4534 thegaragejournal.org 18+ Full terms and conditions of access and use can be found at: https://thegaragejournal.org/en/about/faq#content Curatorial essay Rejecting Normal: Curating Queer British Art, 1861-1967 at Tate Britain and Being Human at Wellcome Collection, London Clare Barlow There has been a number of exhibi- tember 2017) and Being Human tions in the last five years that have (September 2019–present). Drawing explored queer themes and adopted on my experience of curating these queer approaches, yet the posi- projects, I consider their successes tion of queer in museums remains and limitations, particularly with precarious. This article explores regards to intersectionality, and the the challenges of this museological different ways in which queerness landscape and the transformative shaped their conceptual frameworks: potential of queer curating through from queer readings in Queer British two projects: Queer British Art, Art to the explicit rejection of ‘nor- 1861—1967 (Tate Britain, April–Sep- mal’ in Being Human. -

Title: Pastel Painting Grade Level: K - 12 Length: 2 – 45 Min

Title: Pastel Painting Grade Level: k - 12 Length: 2 – 45 min. Visual Arts Benchmarks: VA.68.C.2.3, VA.68.C.3.1, V.A.S.1.4, VA.68.S.2.1, VA.68.S.2.3, VA.68.S.3.4, VA.68.O.1.2, VA.68.O.2.4, VA.68.H.2.3, VA.68.H.3.3, VA.68.F.2.1, VA.68.F.3.4, VA.68.S.3.1, VA.68.C.1.3 Additional Required Benchmarks: LACC.68.RST.2.4, MACC.6.G.1, MACC.7.G.1, MACC.K12.MP.7, LACC.6.SL.2.4, MACC.K12.MP.6 Objectives / Learning Goals: Students explore a combination of Drawing and Painting mediums and techniques to create an impasto piece of artwork that reflects Vincent van Gogh’s unique painting style and imaginative use of color theory. Vocabulary: impasto, pastel, tempera paint, Impressionism, Post- Impressionism, Vincent van Gogh, still life, landscape, portrait, self-portrait, color theory, picture plane, pattern, design Materials: white tempera paint, soft pastels, black construction paper, styrofoam trays, paper towels, sponges, pencils, rulers (optional) Instructional Resources: Pastel Painting power point, Vincent van Gogh art reproductions, Visual Arts textbooks Instructional Delivery of Project: 1. Introduce, analyze, discuss, and evaluate a variety of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings (Pastel Painting ppt.) with emphasis on his subject mater, and use of color theory and painting techniques. Follow with teacher-directed journal reflections. 2. Demonstrate the impasto technique of dipping pastels into white tempera paint and applying to surface of black construction paper. -

By Mike Klozar Have You Dreamed of Visiting London, but Felt It Would

By Mike Klozar Have you dreamed of visiting London, but felt it would take a week or longer to sample its historic sites? Think again. You can experience some of London's best in just a couple of days. Day One. • Thames River Walk. Take a famous London Black Cab to the Tower of London. The ride is an experience, not just a taxi. (15-30 min.) • Explore the Tower of London. Keep your tour short, but be sure to check out the Crown Jewels. (1-2 hrs.) • Walk across the Tower Bridge. It's the fancy blue one. (15 min.) From here you get the best view of the Tower of London for photos. • Cross over to Butler's Wharf and enjoy lunch at one of the riverfront restaurants near where Bridget lived in Bridget Jones's Diary. (1.5 hrs.) • Keeping the Thames on your right, you'll come to the warship HMS Belfast. Tours daily 10 a.m.-4 p.m. (30 min.-1 hr.) • Walk up London Bridge Street to find The Borough Market. Used in countless films, it is said to be the city's oldest fruit and vegetable market, dating from the mid-1200s. (1 hr.) • Back on the river, you'll discover a tiny ship tucked into the docks: a replica of Sir Francis Drake's Golden Hind, which braved pirates in the days of yore. (15 min.) • Notable London pubs are situated along the route and are good for a pint, a cup of tea and a deserved break. Kids are welcome. -

NICK HORNBY Born 1980. Lives and Works in London, England

NICK HORNBY Born 1980. Lives and works in London, England. EDUCATION 2007 MA, Chelsea College of Art 2003 BA, Fine Art, Slade School of Art The Art Institute of Chicago SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Nick Hornby: Sculpture (1504 - 2017), Glyndebourne, UK 2015 Nick Hornby & Sinta Tantra - Collaborative Works II, Choi Lager Gallery, Cologne 2013 Nick Hornby: Sculpture (1504-2013), Churner and Churner, New York Nick Hornby & Sinta Tantra, One Canada Square, London 2011 Matthew Burrows & Nick Hornby, The Solo Projects, Basel 2010 Atom vs Super Subject, Alexia Goethe Gallery, London 2008 Tell Tale Heart, Camley Street Natural Park, London Clifford Chance Sculpture Award 2008, Clifford Chance, London SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 2017 The Curators’ Eggs, Paul Kasmin, New York, NY Nick Hornby & Sinta Tantra - Collaborative Works II, Pinsent Masons LLP, London. Contemporary Sculpture Fulmer, Fulmer Contemporary, UK I Lost My Heart to a Starship Trooper, Griffin Gallery, London 2016 Think Pieces, Cass Sculpture Foundation, UK Reverse Engineering, Waterside Contemporary, London Young Bright Things, David Gill Gallery, London Attitudes Sculpture, Eduardo Secci Gallery, Florence 2015 ALAC, Art Los Angeles Contemporary with Anat Ebgi Gallery 2014 The Last Picture Show, Churner and Churner Gallery, NY Slipped Gears, Eyebeam Centre, Bennington College Art Gallery, Vermont USA Eric Fertman and Nick Hornby, Time Equities Building, New York Bird God Drone, Public Commission, DUMBO, Brookyn, New York 2013 Out of Hand: Materializing the Post-Digital, Museum of Art and Design, New York Ikono On Air Festival, Ikono, Berlin Drawing Biennial 2013, Drawing Room, London 2012 Polish Bienalle: Meditations – The Unknown, Poznan, Poland Sculptors Drawings, Pangolin, London 2011 Aggregate: Nick Hornby, Clare Gasson, Connor Linskey, Churner and Churner, New York Open Prototyping, Eyebeam, New York Are Pictures Always Paintings? Alexia Goethe Gallery, London 2010 Patrons, Muses and Professionals, Eyebeam, New York Volume One: Props, Events and Encounters. -

Never-Before-Seen Documents Reveal IWM's Plan for Evacuating Its Art

Never-before-seen documents reveal IWM’s plan for evacuating its art collection during the Second World War Never-before-seen documents from Imperial War Museums’ (IWM) collections will be displayed as part of a new exhibition at IWM London, uncovering how cultural treasures in British museums and galleries were evacuated and protected during the Second World War. The documents, which include a typed notice issued to IWM staff in 1939, titled ‘Procedure in the event of war,’ and part of a collection priority list dated 1938, are among 15 documents, paintings, objects, films and sculptures that will be displayed as part of Art in Exile (5 July 2019 – 5 January 2020). At the outbreak of the Second World War, a very small proportion of IWM’s collection was chosen for special evacuation, including just 281works of art and 305 albums of photographs. This accounted for less than 1% of IWM’s entire collection and 7% of IWM’s art collection at the time, which held works by prominent twentieth- century artists including William Orpen, John Singer Sargent, Paul Nash and John Lavery. Exploring which works of art were saved and which were not, Art in Exile will examine the challenges faced by cultural organisations during wartime. With the exodus of Britain’s cultural treasures from London to safety came added pressures on museums to strike a balance between protecting, conserving and displaying their collections. The works on IWM’s 1938 priority list, 60 of which will be reproduced on one wall in the exhibition, were destined for storage in the country homes of IWM’s Trustees, where it was believed German bombers were unlikely to venture. -

Self-Portrait on Paper

Self-portrait on Paper Related Visual and Performing Arts Subjects: English-Language Arts Grades: 3-5 Medium: Chalk pastel Author: MCASD Office of Education Time: 90 minute lesson Summary: In this lesson, students will be guided into cre- ating their own self-portrait in steps using col- ored pastels. They will also use their self- portraits as a springboard to write a personal narrative. Materials: Sketchbooks (or unlined paper) Pencils Rulers Chalk pastels Baby wipes (if no sink is available) Pre-made color wheel Color wheels Mirrors Lined paper for personal narrative Strong hairspray or fixative Glossary: Portrait – a picture an artist makes of a person, usually portraying the face. Primary colors – the colors red, blue, and yellow that along with black and white make up all other colors. Primary colors cannot be made by mixing other colors. Secondary colors – when two primaries are mixed together to create a new color. Self-portrait – a portrait that an artist paints of himself or herself. Preparation for Teachers: Prepare images of self portraits – transparencies, handouts, PowerPoint presentations, etc. For digital files of the museum image in this packet, email [email protected]. Practice drawing a self-portrait to feel comfortable with the example. Pre-project class discussion: Begin by stating the objective of the lesson – creating a self-portrait using pencil and chalk. Show examples of self portraits. Ask questions to guide discussion: Why do artists make portraits and self-portraits? What can we learn about the individuals depicted by studying self-portraits? What do you observe? Begin talking about color: What feelings do colors give us? Where do we see people using color to get our attention (TV, advertising, etc.)? What if you only had red, yellow and blue? Could you make other colors from these three? Briefly go over the color wheel. -

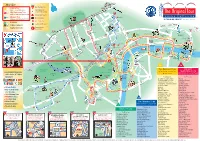

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

Imperialism Tate Britain: Colonialism Tate Britain Has Over 500 Pieces of Art That Are Related to British Colonialism. There Ar

Imperialism Tate Britain: Colonialism Tate Britain has over 500 pieces of art that are related to British Colonialism. There are portraits, propaganda and photographs. Mutiny at the Margin: The Indian Uprising of 1857 2007 saw the 150th Anniversary of the Indian Uprising (also known as the ‘Mutiny') of 1857-58. One of the best-known episodes of both British imperial and South Asian history and a seminal event for Anglo-Indian relations, 1857 has yet to be the subject of a substantial revisionist history British Postal Museum and Archive: British Empire Exhibition Great Britain’s first commemorative stamps were issued on 23 April 1924 – this marked the first day of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. British Cartoon Archive: British Empire The British Cartoon Archive has a collection of 280 contemporary cartoons that are related to the British Empire. The Word on the Street: Emigration This contains a collection of 44 ballads that are related to British emigration during the 1800/1900’s. British Pathe: Empire British Pathe has a collection of contemporary newsreels that are related to the empire. Included, for example, is footage from Empire Day celebration in 1933. The British Library: Asians in Britain These webpages trace the long history of Asians in Britain, focusing on the period 1858-1950. They explore the subject through contemporary accounts, posters, pamphlets, diaries, newspapers, political reports and illustrations, all evidence of the diverse and rich contributions Asians have made to British life. The National Archives: British Empire The National Archives has an exhibition that analyses the growth of the British Empire. -

Lesson Plans All Grade Levels Preschool Art Ideas

Lesson Plans All Grade Levels Preschool Art Ideas Children of preschool age and younger can make colorful pictures of their own that look great on all Art to Remember products. Here are several examples that have worked well with past customers. See more at www.ArttoRemember.com! Handprint and footprint art can be used to make anything from fun bugs, tame or wild animals and funny frogs and fish! Hand Stamp Flower Painting Preschool Objective Children will learn about colors, textures, and different art mediums. Textured Background Sponged Background Required Materials Pictures of flowers from seed catalogues, calendars, fresh flowers, silk flowers, and artists floral paintings 8" x 10.5" art paper provided by Art to Remember Washable paint, (tempera or poster paint but not fluorescent), crayons (large), texture boards or any material that has a texture on it, paint brushes, Styrofoam trays or cookie sheets Instructions 1. Prepare background. Place paper over textured surface and rub surface lightly with broad side of color crayons that have had paper removed. You may overlap several colors for a different effect. Sponge painting the background is another option. 2. Painting process. Pour small amounts of paint in trays in a variety of colors. Press child’s hand in desired color and carefully print on an area of paper where flower is to be placed. Add one or more flowers to complete stamping. Using paint brushes, have the children add leaves and details to complete their paintings. 3. Print name legibly at least an inch from the edge of the paper so the name will not be lost in printing. -

Two Artworks by Jock Mcfadyen to Go on Permanent Display at IWM North As Imperial War Museums Marks 30 Years Since the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Two artworks by Jock McFadyen to go on permanent display at IWM North as Imperial War Museums marks 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall To coincide with the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Christmas in Berlin (1991) and Die Mauer (1991), painted by renowned artist Jock McFadyen, will be going on permanent display at IWM North. This is the first time in over a decade that the paintings have been on public display. The fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 signalled the end of the Cold War, triggering the reunification of Germany and the subsequent dissolution of the USSR. Europe was reshaped, both in its physical borders and its political and social identity, which continue to evolve today. In 1990, the year following the fall of the Berlin Wall, Scottish artist Jock McFadyen was commissioned by Imperial War Museums to respond to this momentous event in history and to record its impact on the city and its residents. In Christmas in Berlin (left), McFadyen blurs the distinction between the Wall and the cityscape of Berlin. The Wall can be seen covered in vividly coloured markings and large-scale symbols representing graffiti, set against a wintry grey background. In the distance, festival lights, one in the shape of a Christmas tree, shine dimly against the buildings. Beyond the Wall, the iconic sphere of the Berliner Fernsehturm (Television Tower) in Alexanderplatz dominates the skyline. During the Cold War, residents of East Berlin would visit the top of the Tower, which was the highest point in the city, to view the West.