The Industrialization of the London Beer-Brewing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brewing Yeast – Theory and Practice

Brewing yeast – theory and practice Chris Boulton Topics • What is brewing yeast? • Yeast properties, fermentation and beer flavour • Sources of yeast • Measuring yeast concentration The nature of yeast • Yeast are unicellular fungi • Characteristics of fungi: • Complex cells with internal organelles • Similar to plants but non-photosynthetic • Cannot utilise sun as source of energy so rely on chemicals for growth and energy Classification of yeast Kingdom Fungi Moulds Yeast Mushrooms / toadstools Genus > 500 yeast genera (Means “Sugar fungus”) Saccharomyces Species S. cerevisiae S. pastorianus (ale yeast) (lager yeast) Strains Many thousands! Biology of ale and lager yeasts • Two types indistinguishable by eye • Domesticated by man and not found in wild • Ale yeasts – Saccharomyces cerevisiae • Much older (millions of years) than lager strains in evolutionary terms • Lot of diversity in different strains • Lager strains – Saccharomyces pastorianus (previously S. carlsbergensis) • Comparatively young (probably < 500 years) • Hybrid strains of S. cerevisiae and wild yeast (S. bayanus) • Not a lot of diversity Characteristics of ale and lager yeasts Ale Lager • Often form top crops • Usually form bottom crops • Ferment at higher temperature o • Ferment well at low temperatures (18 - 22 C) (5 – 10oC) • Quicker fermentations (few days) • Slower fermentations (1 – 3 weeks) • Can grow up to 37oC • Cannot grow above 34oC • Fine well in beer • Do not fine well in beer • Cannot use sugar melibiose • Can use sugar melibiose Growth of yeast cells via budding + + + + Yeast cells • Each cell is ca 5 – 10 microns in diameter (1 micron = 1 millionth of a metre) • Cells multiply by budding a b c d h g f e Yeast and ageing - cells can only bud a certain number of times before death occurs. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title In danger of undoing: The Literary Imagination of Apprentices in Early Modern London Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1fx380bc Author Drosdick, Alan Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California In danger of undoing: The Literary Imagination of Apprentices in Early Modern London by Alan J. Drosdick A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Joel B. Altman, Chair Professor Jeffrey Knapp Professor Albert Russell Ascoli Fall 2010 Abstract In danger of undoing: The Literary Imagination of Apprentices in Early Modern London by Alan J. Drosdick Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Joel B. Altman, Chair With the life of the apprentice ever in mind, my work analyzes the underlying social realities of plays such as Dekker’s The Shoemaker’s Holiday, Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle, Jonson, Chapman, and Marston’s Eastward Ho!, and Shakespeare’s Henriad. By means of this analysis, I reopen for critical investigation a conventional assumption about the mutually disruptive relationship between apprentices and the theater that originated during the sixteenth century and has become a cliché of modern theater history at least since Alfred Harbage’s landmark Shakespeare’s Audience (1941). As a group, apprentices had two faces in the public imagination of renaissance London. The two models square off in Eastward Ho!, where the dutiful Golding follows his master’s orders and becomes an alderman, while the profligate Quicksilver dallies at theaters and ends up in prison. -

To Many Beer Lovers, Christian Monks

The history of monks and brewing To many beer lovers, Christian monks are the archetypes of brewers. It’s not that monks invented beer: Archeologists find it in both China and Egypt around 5000 B.C., long before any Christian monks existed. And it’s not that the purpose of monks is to brew beer: Their purpose is to seek and to serve God, through a specific form of spiritual life. But if monks did not invent beer, and brewing is not their defining vocation, they did play a major role in Western brewing from at least the second half of the first millennium. Let’s take a broad look at how. First, some background. Christian monasticism has its formal roots in the fourth century, when the Roman Empire was still at its height. The Empire suffered serious decline during the fifth century, the era in which St. Benedict lived (c. 480 - March 21, 547). As the social structure of the Roman Empire crumbled, monasteries organized under the Rule of Benedict emerged as centers of agriculture, lodging, education, literature, art, etc. When Charlemagne established the Holy Roman Empire in the year 800, he relied on monasteries to help weave its social and economic infrastructure – and he promoted the Rule of Benedict as the standard for monastic organization. Against this brief sketch of history, we can begin to observe the relationship between monks and brewing. In ancient days, within the Roman Empire as throughout the world, brewing was typically done in the home. This practice carried into monasteries, which had to provide drink and nourishment for the monks, as well as for guests, pilgrims, and the poor. -

JMU Overpowers Providence 94-74; Meet Buckeyes for Sunday Showdown Dukes Wrest CAA Title in See-Saw Game

London: JMU students dd the town, Brit-style THURSDAY, MARCH 16, 1989 JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY VOL. 66 NO. 43 JMU overpowers Providence 94-74; meet Buckeyes for Sunday showdown By Eric Vazzana and 18 points and fueling a second half run John R. Craig that put the game away. staff writers Carolin Dchn-Duhr continued to play The big party got underway last night inspired ball on the inside as she at the Convocation Center as the JMU collected 24 points and grabbed nine women's basketball team spoiled the rebounds. Missy Dudley turned in her visiting Providence Friars' upset bid and usual steady game, chipping in with 20 cruised to a 94-74 victory. points and six rebounds. Dudley was also given the assignment of shutting JMU shot a blistering 60 percent down the Friars' primary outside threat from the field in the first half, including Tracy Lis. Lis shot a dismal four-for-14 going scven-for-seven to open the first and was ineffective all night. round of the NCAA women's basketball It was a JMU team effort in every tournament. The Dukes advance, to the phase of the game that left Providence second round of the tourney riding a head coach Bob Folcy searching for 12-game win streak and will face Ohio ways to stop the Dukes all night. State Sunday on the Buckeye's home What went wrong is James Madison court in Columbus, Ohio. shot, what, about 88 percent?" said JMU head coach Shclia Moorman felt Folcy. "We knew that Carolin her team would have to play medium Dehn-Duhr was a strong inside player, I tempo to win and play at "our usual knew that Dudley could shoot the intensity." jumper. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

BUCKING Hal\T!SHIRE. FAR 259

TRADES DIRECTORY.] BUCKING HAl\t!SHIRE. FAR 259 Tack Thomas, The Firs, Steeple Clay- TownsendJohnEmberton,Newprt. Pagnll Webb Joseph, Mount Pleasant, ~fiddle don, Winslow Townsend J. W. Gayhurst, :Newprt. Pgnll Craydon, Steeple Claydon S.O Talbot William, The Hyde, Olney S.O Treadwell J. Winchendon Up. Aylesbury Webster Samuel, North Crawley, New- Tanner Henry, Twyford, Buckingham Treadwell Samuel, Windmill hill, Wad- port Pagnell Tapping Henry, Wendover dean, Wen- desdon, Aylesbury WeedonThomasBrown,NewHousefarm, dover, Tring Treadwell Tom, Stowe, Buckingham Chalfont St. Giles,Gerrard's Cross R.S.O TappingJ. H. Weston Turville, Aylesbury Treadwell J. jun. Tingewick, Buckingham Welch George, Gold hill, Chalfont St. Tapping John Henry, Manor farm, Stoke Tucker John, Little Totteridge, Hazle- Peter, Gerrard's Cross R.S.O Mandeville, Aylesbury mere, High Wycombe Welch T. Layter's green, Chalfont St. Tarrant J. Eton wick, Eton, Winsdor Turner W. Great Brickhill, Bletchley Peter, Gerrard's Cross R.S.O Tattam John, Deverells, Swanbrne. W nslw Turney C. T. Chicheley, K ewport Pagnell Wells J ames, Ley hill, Chesham R.S.O Tayler G. Kickles frm. Newport Pagnell Turney J. Slapton, Leighton Buzzard West Arthur, Twigside, Ibstone, Tetswrth Taylor David, Haddenham, Thame TurneyJameFJ,Soulbury,LeightonBuzzrd West GBo. Stokenchurch, Wallingford Taylor G. Little Missenden, Amersham Turnham Henry, London road, Wycombe West Geor"e, Hundridae, Chesham R.S.O Taylor Henry, Newton Blossom ville, Twidell W. Dagnall, Great Berkhamstead West Robe~t, Daws hill~Radnage, Stoken- Newport Pagnell Tyler Thomas, Loosely row, Princes church, Wallingford Taylor J. Milton Keynes, Nwprt. Pagnell Risborough S.O West W. Lewkner-up-Hill,High Wycombe Taylor James, Lane farm, Kingswood, Uff Richard, Westcott, Aylesbury Westaway Mark A. -

Bledlow Beechwoods and Bledda’S Rest

point your feet on a new path Bledlow Beechwoods and Bledda’s Rest Distance: 16 km=10 miles moderate walking Region: Chilterns Date written: 2-sep-2010 Author: Phegophilos Date revised: 27-aug-2018 Refreshments: Bledlow, Bennett End Last update: 17-nov-2020 Maps: Explorer 181 (Chiltern Hills North), Explorer 171 (Chiltern Hills West) (hopefully not needed) Problems, changes? We depend on your feedback: [email protected] Public rights are restricted to printing, copying or distributing this document exactly as seen here, complete and without any cutting or editing. See Principles on main webpage. Village, woodland, nature reserves, hills, views In Brief This truly unforgettable walk shows you all that is best in the Chiltern Hills. You go through great beechwoods, along valleys and over the Bledlow Ridge with terrific views. The walk begins and ends in a snug Chiltern village which holds its own surprises. The village has one of the iconic pubs of the Chilterns (to enquire at the Lions of Bledlow , ring 01844-343345). Along the way, you can stop at the Boot in the Ridge (ring 01494-481499). You also pass one of the great foodie pubs (see text), requiring long advance booking. This walk is a tribute to Raymond Hugh’s Adventurous Walks books, since it follows the same route as one of his walks. These books are out of print but still possibly available by mail order and the other nine walks are also a pleasure to do. There are only a few nettles on this walk and sensible shoes should be adequate in dry weather. -

Swivel-Eyed Loons Had Found Their Cheerleader at Last: Like Nobody Else, Boris Could Put a Jolly Gloss on Their Ugly Tale of Brexit As Cultural Class- War

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau FURTHER PRAISE FOR JAMES HAWES ‘Engaging… I suspect I shall remember it for a lifetime’ The Oldie on The Shortest History of Germany ‘Here is Germany as you’ve never known it: a bold thesis; an authoritative sweep and an exhilarating read. Agree or disagree, this is a must for anyone interested in how Germany has come to be the way it is today.’ Professor Karen Leeder, University of Oxford ‘The Shortest History of Germany, a new, must-read book by the writer James Hawes, [recounts] how the so-called limes separating Roman Germany from non-Roman Germany has remained a formative distinction throughout the post-ancient history of the German people.’ Economist.com ‘A daring attempt to remedy the ignorance of the centuries in little over 200 pages... not just an entertaining canter -

Community and Childrens Services Terms of Reference

WOOTTON, Mayor RESOLVED: That the Court of Common Council holden in the Guildhall of the City of London on Thursday 19th April 2012, doth hereby appoint the following Committee until the first meeting of the Court in April, 2013. COMMUNITY & CHILDREN’S SERVICES COMMITTEE 1. Constitution A Ward Committee consisting of, two Aldermen nominated by the Court of Aldermen up to 33 Commoners representing each Ward (two representatives for the Wards with six or more Members regardless of whether the Ward has sides), those Wards having 200 or more residents (based on the Ward List) being able to nominate a maximum of two representatives a limited number of Members co-opted by the Committee (e.g. the two parent governors required by law) In accordance with Standing Order Nos. 29 & 30, no Member who is resident in, or tenant of, any property owned by the City of London and under the control of this Committee is eligible to be Chairman or Deputy Chairman. 2. Quorum The quorum consists of any nine Members. [N.B. - the co-opted Members only count as part of the quorum for matters relating to the Education Function] 3. Membership 2012/13 ALDERMEN 1 The Hon. Philip John Remnant, C.B.E. 1 New Alderman for the Ward of Aldgate COMMONERS 7 The Revd. Dr. Martin Dudley ………………………………………………………………….Aldersgate 2 Joyce Carruthers Nash, O.B.E., Deputy .........................................................................Aldersgate 4 Hugh Fenton Morris .......................................................................................................Aldgate -

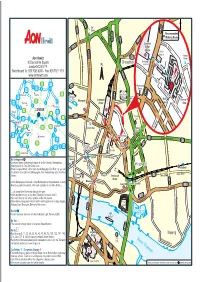

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

The Theological Socialism of the Labour Church

‘SO PECULIARLY ITS OWN’ THE THEOLOGICAL SOCIALISM OF THE LABOUR CHURCH by NEIL WHARRIER JOHNSON A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The thesis argues that the most distinctive feature of the Labour Church was Theological Socialism. For its founder, John Trevor, Theological Socialism was the literal Religion of Socialism, a post-Christian prophecy announcing the dawn of a new utopian era explained in terms of the Kingdom of God on earth; for members of the Labour Church, who are referred to throughout the thesis as Theological Socialists, Theological Socialism was an inclusive message about God working through the Labour movement. By focussing on Theological Socialism the thesis challenges the historiography and reappraises the significance of the Labour -

861 Sq Ft Headquarters Office Building Your Own Front Door

861 SQ FT HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDING YOUR OWN FRONT DOOR This quite unique property forms part of the building known as Rotherwick House. The Curve comprises a self-contained building, part of which is Grade II Listed, which has been comprehensively refurbished to provide bright contemporary Grade A office space. The property — located immediately to the east of St Katharine’s Dock and adjoining Thomas More Square — benefits from the immediate area which boasts a wide variety of retail and restaurant facilities. SPECIFICATION • Self-contained building • Generous floor to ceiling heights • New fashionable refurbishment • Full-height windows • New air conditioning • Two entrances • Floor boxes • Grade II Listed building • LG7 lighting with indirect LED up-lighting • Fire and security system G R E A ET T THE TEA TRE E D S A BUILDING OL S T E R SHOREDITCH N S HOUSE OLD STREET T R E E T BOX PARK AD L RO NWEL SHOREDITCH CLERKE C I HIGH STREET T Y R G O O A S D W S F H A O E R L U A L R T AD T H I O R T R N A S STEPNEY D’ O O M AL G B N A GREEN P O D E D T H G O T O WHITECHAPEL A N N R R R O D BARBICAN W O CHANCERY E A FARRINGDON T N O LANE D T T E N H A E M C T N O C LBOR A D O HO M A IGH MOORGATE G B O H S R R U TOTTENHAM M L R LIVERPOOL P IC PE T LO E COURT ROAD NDON WA O K A LL R N R H STREET H C L C E E O S A I SPITALFIELDS I IT A A W B N H D L E W STE S R PNEY WAY T O J R U SALESFORCE A E HOLBORN B T D REE TOWER E ST N I D L XFOR E G T O W R E K G ES H ALDGATE I A H E N TE A O M LONDON MET.