Ecdysozoa - Andreas Schmidt-Rhaesa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 4 Plant and Animal Classification and Identification

LESSON 4 PLANT AND ANIMAL CLASSIFICATION AND IDENTIFICATION Aim Become familiar with the basic ways in which plants and animals can be classified and identified CLASSIFICATION OF ORGANISMS Living organisms that are relevant to the ecotourism tour guide are generally divided into two main groups of things: ANIMALS........and..........PLANTS The boundaries between these two groups are not always clear, and there is an increasing tendency to recognise as many as five or six kingdoms. However, for our purposes we will stick with the two kingdoms. Each of these main groups is divided up into a number of smaller groups called 'PHYLA' (or Phylum). Each phylum has certain broad characteristics which distinguish it from other groups of plants or animals. For example, all flowering plants are in the phyla 'Anthophyta' (if a plant has a flower it is a member of the phyla 'Anthophyta'). All animals which have a backbone are members of the phyla 'Vertebrate' (i.e. Vertebrates). Getting to know these major groups of plants and animals is the first step in learning the characteristics of, and learning to identify living things. You should try to gain an understanding of the order of the phyla - from the simplest to the most complex - in both the animal and plant kingdoms. Gaining this type of perspective will provide you with a framework which you can slot plants or animals into when trying to identify them in nature. Understanding the phyla is only the first step, however. Phyla are further divided into groups called 'classes'. Classes are divided and divided again and so on. -

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Platyhelminthes, Nemertea, and "Aschelminthes" - A

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCE FUNDAMENTALS AND SYSTEMATICS – Vol. III - Platyhelminthes, Nemertea, and "Aschelminthes" - A. Schmidt-Rhaesa PLATYHELMINTHES, NEMERTEA, AND “ASCHELMINTHES” A. Schmidt-Rhaesa University of Bielefeld, Germany Keywords: Platyhelminthes, Nemertea, Gnathifera, Gnathostomulida, Micrognathozoa, Rotifera, Acanthocephala, Cycliophora, Nemathelminthes, Gastrotricha, Nematoda, Nematomorpha, Priapulida, Kinorhyncha, Loricifera Contents 1. Introduction 2. General Morphology 3. Platyhelminthes, the Flatworms 4. Nemertea (Nemertini), the Ribbon Worms 5. “Aschelminthes” 5.1. Gnathifera 5.1.1. Gnathostomulida 5.1.2. Micrognathozoa (Limnognathia maerski) 5.1.3. Rotifera 5.1.4. Acanthocephala 5.1.5. Cycliophora (Symbion pandora) 5.2. Nemathelminthes 5.2.1. Gastrotricha 5.2.2. Nematoda, the Roundworms 5.2.3. Nematomorpha, the Horsehair Worms 5.2.4. Priapulida 5.2.5. Kinorhyncha 5.2.6. Loricifera Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS This chapter provides information on several basal bilaterian groups: flatworms, nemerteans, Gnathifera,SAMPLE and Nemathelminthes. CHAPTERS These include species-rich taxa such as Nematoda and Platyhelminthes, and as taxa with few or even only one species, such as Micrognathozoa (Limnognathia maerski) and Cycliophora (Symbion pandora). All Acanthocephala and subgroups of Platyhelminthes and Nematoda, are parasites that often exhibit complex life cycles. Most of the taxa described are marine, but some have also invaded freshwater or the terrestrial environment. “Aschelminthes” are not a natural group, instead, two taxa have been recognized that were earlier summarized under this name. Gnathifera include taxa with a conspicuous jaw apparatus such as Gnathostomulida, Micrognathozoa, and Rotifera. Although they do not possess a jaw apparatus, Acanthocephala also belong to Gnathifera due to their epidermal structure. ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) BIOLOGICAL SCIENCE FUNDAMENTALS AND SYSTEMATICS – Vol. -

New Zealand's Genetic Diversity

1.13 NEW ZEALAND’S GENETIC DIVERSITY NEW ZEALAND’S GENETIC DIVERSITY Dennis P. Gordon National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie, Wellington 6022, New Zealand ABSTRACT: The known genetic diversity represented by the New Zealand biota is reviewed and summarised, largely based on a recently published New Zealand inventory of biodiversity. All kingdoms and eukaryote phyla are covered, updated to refl ect the latest phylogenetic view of Eukaryota. The total known biota comprises a nominal 57 406 species (c. 48 640 described). Subtraction of the 4889 naturalised-alien species gives a biota of 52 517 native species. A minimum (the status of a number of the unnamed species is uncertain) of 27 380 (52%) of these species are endemic (cf. 26% for Fungi, 38% for all marine species, 46% for marine Animalia, 68% for all Animalia, 78% for vascular plants and 91% for terrestrial Animalia). In passing, examples are given both of the roles of the major taxa in providing ecosystem services and of the use of genetic resources in the New Zealand economy. Key words: Animalia, Chromista, freshwater, Fungi, genetic diversity, marine, New Zealand, Prokaryota, Protozoa, terrestrial. INTRODUCTION Article 10b of the CBD calls for signatories to ‘Adopt The original brief for this chapter was to review New Zealand’s measures relating to the use of biological resources [i.e. genetic genetic resources. The OECD defi nition of genetic resources resources] to avoid or minimize adverse impacts on biological is ‘genetic material of plants, animals or micro-organisms of diversity [e.g. genetic diversity]’ (my parentheses). -

Nematode Management for Bedding Plants1 William T

ENY-052 Nematode Management for Bedding Plants1 William T. Crow2 Florida is the “land of flowers.” Surely, one of the things that Florida is known for is the beauty of its vegetation. Due to the tropical and subtropical environment, color can abound in Florida landscapes year-round. Unfortunately, plants are not the only organisms that enjoy the mild climate. Due to warm temperatures, sandy soil, and humidity, Florida has more than its fair share of pests and pathogens that attack bedding plants. Plant-parasitic nematodes (Figure 1) can be among the most damaging and hard-to-control of these organisms. What are nematodes? Nematodes are unsegmented roundworms, different from earthworms and other familiar worms that are segmented (annelids) or in some cases flattened and slimy (flatworms). Many kinds of nematodes may be found in the soil of any landscape. Most are beneficial, feeding on bacteria, fungi, or other microscopic organisms, and some may be used as biological control organisms to help manage important insect pests. Plant-parasitic nematodes are nematodes that Figure 1. Diagram of a generic plant-parasitic nematode. feed on live plants (Figure 1). Credits: R. P. Esser, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry; used with permission. Plant-parasitic nematodes are very small and most can only be seen using a microscope (Figure 2). All plant-parasitic nematodes have a stylet or mouth-spear that is similar in structure and function to a hypodermic needle (Figure 3). 1. This document is ENY-052, one of a series of the Department of Entomology and Nematology, UF/IFAS Extension. -

Nematicidal Properties of Some Algal Aqueous Extracts Against Root-Knot Nematode, Meloidogyne Incognita in Vitro

6 Egypt. J. Agronematol., Vol. 15, No.1, PP. 67-78 (2016) Nematicidal properties of some algal aqueous extracts against root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita in vitro Ahmed H. Nour El-Deen(*,***)and Ahmed A. Issa(**,***) * Nematology Research Unit, Agricultural Zoology Dept., Faculty of Agriculture, Mansoura University, Egypt. ** Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Assiut University, Assiut , Egypt. *** Biology Dept., Faculty of Science, Taif University, Saudi Arabia. Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The effectiveness of aqueous extracts derived from nine algal species at different concentrations on egg hatching and mortality of Meloidogyne incognita (Kofoid and White) Chitwood juveniles after various exposure times were determined in vitro. Results indicated that Enteromorpha flexuosa at the concentration of 80% was the best treatment for suppressing the egg hatching with value of 2 % after 5 days of exposure, followed by Dilsea carnosa extract (3%) and Codium fragile (4%) at the same concentration and exposure time. Likewise, application of C. fragile, D. carnosa , E. flexuosa and Cystoseira myrica extracts at the concentrations of 80 and 60% were highly toxic to the nematodes, killing more than 90 % of nematode larva after 72 hours of exposure while the others gave quite low mortalities. The characteristic appearances in shape of the nematodes killed by C. fragile, D. carnosa , C. myrica, E. flexuosa and Sargassum muticum was sigmoid (∑-shape) with some curved shape; whereas, the nematodes killed by other algal species mostly followed straight or bent shapes. The present study proved that four species of algae C. fragile, D. carnosa, C. myrica and E. flexuosa could be used for the bio-control of root-knot nematodes. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

Arachnida, Solifugae) with Special Focus on Functional Analyses and Phylogenetic Interpretations

HISTOLOGY AND ULTRASTRUCTURE OF SOLIFUGES Comparative studies of organ systems of solifuges (Arachnida, Solifugae) with special focus on functional analyses and phylogenetic interpretations HISTOLOGIE UND ULTRASTRUKTUR DER SOLIFUGEN Vergleichende Studien an Organsystemen der Solifugen (Arachnida, Solifugae) mit Schwerpunkt auf funktionellen Analysen und phylogenetischen Interpretationen I N A U G U R A L D I S S E R T A T I O N zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität Greifswald vorgelegt von Anja Elisabeth Klann geboren am 28.November 1976 in Bremen Greifswald, den 04.06.2009 Dekan ........................................................................................................Prof. Dr. Klaus Fesser Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Gerd Alberti Erster Gutachter .......................................................................................... Zweiter Gutachter ........................................................................................Prof. Dr. Romano Dallai Tag der Promotion ........................................................................................15.09.2009 Content Summary ..........................................................................................1 Zusammenfassung ..........................................................................5 Acknowledgments ..........................................................................9 1. Introduction ............................................................................ -

Multi-Gene Analyses of the Phylogenetic Relationships Among the Mollusca, Annelida, and Arthropoda Donald J

Zoological Studies 47(3): 338-351 (2008) Multi-Gene Analyses of the Phylogenetic Relationships among the Mollusca, Annelida, and Arthropoda Donald J. Colgan1,*, Patricia A. Hutchings2, and Emma Beacham1 1Evolutionary Biology Unit, The Australian Museum, 6 College St. Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia 2Marine Invertebrates, The Australian Museum, 6 College St., Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia (Accepted October 29, 2007) Donald J. Colgan, Patricia A. Hutchings, and Emma Beacham (2008) Multi-gene analyses of the phylogenetic relationships among the Mollusca, Annelida, and Arthropoda. Zoological Studies 47(3): 338-351. The current understanding of metazoan relationships is largely based on analyses of 18S ribosomal RNA ('18S rRNA'). In this paper, DNA sequence data from 2 segments of 28S rRNA, cytochrome c oxidase subunit I, histone H3, and U2 small nuclear (sn)RNA were compiled and used to test phylogenetic relationships among the Mollusca, Annelida, and Arthropoda. The 18S rRNA data were included in the compilations for comparison. The analyses were especially directed at testing the implication of the Eutrochozoan hypothesis that the Annelida and Mollusca are more closely related than are the Annelida and Arthropoda and at determining whether, in contrast to analyses using only 18S rRNA, the addition of data from other genes would reveal these phyla to be monophyletic. New data and available sequences were compiled for up to 49 molluscs, 33 annelids, 22 arthropods, and 27 taxa from 15 other metazoan phyla. The Porifera, Ctenophora, and Cnidaria were used as the outgroup. The Annelida, Mollusca, Entoprocta, Phoronida, Nemertea, Brachiopoda, and Sipuncula (i.e., all studied Lophotrochozoa except for the Bryozoa) formed a monophyletic clade with maximum likelihood bootstrap support of 81% and a Bayesian posterior probability of 0.66 when all data were analyzed. -

Worms, Nematoda

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 2001 Worms, Nematoda Scott Lyell Gardner University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Gardner, Scott Lyell, "Worms, Nematoda" (2001). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 78. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, Volume 5 (2001): 843-862. Copyright 2001, Academic Press. Used by permission. Worms, Nematoda Scott L. Gardner University of Nebraska, Lincoln I. What Is a Nematode? Diversity in Morphology pods (see epidermis), and various other inverte- II. The Ubiquitous Nature of Nematodes brates. III. Diversity of Habitats and Distribution stichosome A longitudinal series of cells (sticho- IV. How Do Nematodes Affect the Biosphere? cytes) that form the anterior esophageal glands Tri- V. How Many Species of Nemata? churis. VI. Molecular Diversity in the Nemata VII. Relationships to Other Animal Groups stoma The buccal cavity, just posterior to the oval VIII. Future Knowledge of Nematodes opening or mouth; usually includes the anterior end of the esophagus (pharynx). GLOSSARY pseudocoelom A body cavity not lined with a me- anhydrobiosis A state of dormancy in various in- sodermal epithelium. -

Outlines of the Natural History of Great Britain and Ireland, Containing A

TK D. H. HILL im^ NORTH C«0Liri>4 ST4TE C0LLC6C & tXUMi. COi QH 13-1 \h ^.<^^ ENT0M0L0aiC4L COLLECTION This book must not be taken from the Library building. 25M JUNE 58 FORM 2 OUTLINES O F T H E NATURAL HISTORY O F G R E AT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. CONTAIN ING A fyftematic Arrangement and concife Defcription of all the Animals, Vegetables, and Foffiles which have hitherto been difcovered in thefe Kingdoms. By JOHN BERKENHOUT, M. D. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. I. Comprehending the Animal Kingdom. LONDON: Printed for P. Elmsly (SuccefTor to Mr. Va ill ant) facing Southampton-llreet, in the Strand. M DCC LXIX. T O THE RIGHT HONORABLE THOMAS LORD VISCOUNT WEYMOUTH. My Lord, IPrefume to dedicate to Your Lord- fliip the refult of my amufement during my late refidence in the Coun- try ; a book which, for the fake of this Nation, I requeffc that you will never read. The fubjecfl, though of confequence to fome individuals, is be- A 2 neath N iv DEDICATION. neath the attention of a Secretary of State. But no man knows better than Your Lordfhip tlie importance of the man is lefs office you fill -, therefore no likely to indulge in trivial ftudies or amufements. Why then, it may be aflced, do I trouble You with a book, with the fubjed: of which You ought to remain afk unacquainted ? If Your Lordfhip the queftion, I will honeftly tell You, that my motives are gratitude and va- it is nity. With regard to the firft, which all I have to offer for obligations concerning I can never forget j and oppor- the latter, I could not refift the that I tunity of boafting to the world, of am not difregarded by a Minifter State, DEDICATION. -

Lecture 16. Endocrine System II

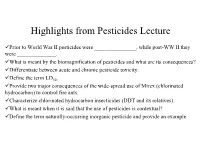

Highlights from Pesticides Lecture Prior to World War II pesticides were _______________, while post-WW II they were ______________. What is meant by the biomagnification of pesticides and what are its consequences? Differentiate between acute and chronic pesticide toxicity. Define the term LD50. Provide two major consequences of the wide-spread use of Mirex (chlorinated hydrocarbon) to control fire ants. Characterize chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides (DDT and its relatives). What is meant when it is said that the use of pesticides is contextual? Define the term naturally-occurring inorganic pesticide and provide an example. Highlights from Biological Control Lecture Define the three types of biological control and provide an example of each. Contrast predators and parasitoids. What is a density-dependent mortality factor? How has the introduction of the soybean aphids affected pest management in the Midwest? Name one untoward effect related to controlling tamarisk trees on the Colorado River. What is meant by an inoculative release of a biological control agent? How do pesticide economic thresholds affect biological control programs? Lecture 19. Endocrine system II Physiological functions of hormones • Anatomy • Hormones: 14 • Functions Functions of insect hormones: diversity Hormonal functions: Molting as a paradigm egg Eat and grow Bridge Disperse and passage reproduce embryo Postembryonic sequential polymorphism • Nature of molting, growth or metamorphosis? • When and how to molt? The molting process Ecdysis phase Pre-ecdysis phase Post-ecdysis phase Overview • About 90 years’ study (1917-2000): 7 hormones are involved in regulating molting / metamorphosis • 3 in Pre-ecdysis preparatory phase: the initiation and determination of new cuticle formation and old cuticle digestion, regulated by PTTH, MH (Ecdysteroids), and JH • 3 in Ecdysis phase: Ecdysis, i.e.