Defining the Liminal Athlete: an Exploration of the Multi-Dimensional Liminal Condition in Professional Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Stormwater Management Report

Municipality/Organization: Boston Water and Sewer Commission EPA NPDES Permit Number: MASO 10001 Report/Reporting Period: January 1, 2017-December 31, 2017 NPDES Phase I Permit Annual Report General Information Contact Person: Amy M. Schofield Title: Project Manager Telephone #: 617-989-7432 Email: [email protected] Certification: I certify under penalty of law that this document and all attachments were prepared under my direction or supervision in accordance with a system designed to assure that qualified personnel properly gather and evaluate the information submitted. Based on my inquiry of the person or persons who manage the system, or those persons directly responsible for gathering the information, the information submitted is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, true, accuratnd complete. I am aware that there are significant penalties for submitting false ivfothnation intdng the possibiLity of fine and imprisonment for knowing violatti Title: Chief Engineer and Operations Officer Date: / TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Permit History…………………………………………….. ……………. 1-1 1.2 Annual Report Requirements…………………………………………... 1-1 1.3 Commission Jurisdiction and Legal Authority for Drainage System and Stormwater Management……………………… 1-2 1.4 Storm Drains Owned and Stormwater Activities Performed by Others…………………………………………………… 1-3 1.5 Characterization of Separated Sub-Catchment Areas….…………… 1-4 1.6 Mapping of Sub-Catchment Areas and Outfall Locations ………….. 1-4 2.0 FIELD SCREENING, SUB-CATCHMENT AREA INVESTIGATIONS AND ILLICIT DISCHARGE REMEDIATION 2.1 Field Screening…………………………………………………………… 2-1 2.2 Sub-Catchment Area Prioritization…………………………………..… 2-4 2.3 Status of Sub-Catchment Investigations……………………….…. 2-7 2.4 Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination Plan ……………………… 2-7 2.5 Illicit Discharge Investigation Contracts……………….………………. -

WORLD FLYING DISC FEDERATION (A Colorado Nonprofit Corporation, As Approved by Congress on 1 January 2019)

BYLAWS OF THE WORLD FLYING DISC FEDERATION (a Colorado Nonprofit Corporation, as approved by Congress on 1 January 2019) ARTICLE I - PURPOSES The World Flying Disc Federation (“WFDF”) is organized exclusively for educational purposes and to foster national and international amateur sports competition within the meaning of and pursuant to Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (or under the corresponding provision of any future United States Internal Revenue law). The activities of WFDF include, but are not limited to, such purposes as: 1. To serve as the international governing body of all flying disc sports, with responsibility for sanctioning world championship and other international flying disc events, establishing uniform rules, and setting standards for and recording of world records; 2. To promote and protect the “spirit of the game” and the principle of “self-officiation" as essential aspects of flying disc sports play; 3. To promote flying disc sports play throughout the world and foster the establishment of new national flying disc sports associations, advising them on all flying disc sports activities and general management; 4. To promote and raise public awareness of and lobby for official recognition of flying disc play as sport; 5. To provide an international forum for discussion of all aspects of flying disc sports play; and 6. Consistent with above principles, to transact any and all other lawful business or businesses for which a corporation may be incorporated pursuant to the Colorado Revised Nonprofit Corporation Act, as it may be amended from time to time. ARTICLE II – DEFINITIONS OF DISC SPORTS AND SANCTIONED EVENTS 1. -

PUBLIC INFORMATION PLAN Prepared By: O’Neill and Associates June 2019 GO SLOW in CAMBRIDGE

PUBLIC INFORMATION PLAN Prepared by: O’Neill and Associates June 2019 GO SLOW IN CAMBRIDGE. LIFE ISN’T A RACE. 31 NEW CHARDON STREET BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02114 (617) 646-1000 Table of Contents I. Vision Zero Strategic Communications Goals II. Key Messages III. Vision Zero Tactical Toolbox IV. Evaluation of Public Education Initiative V. Media Partnership Recommendations VI. Community Organizations VII. Design Examples VIII. Appendix – MBTA Specs VISION ZERO CAMBRIDGE PUBLIC INFORMATION PLAN JUNE 2019 Vision Zero Strategic Communications Goals Working with Vision Zero and City of Cambridge staff, we have identified a number of strategic communications goals for the Vision Zero initiative as it relates to the public education component of the action plan. A comprehensive and successful public relations strategy will only be achieved by knowing the objectives that the organization wishes to attain. As such, below we have outlined the recommendations for Vision Zero’s strategic communications goals based on our discussion: 1. Develop an easy-to-understand but relevant message for those living in Cambridge and those who drive through it regarding the need for slower, safer driving. 2. Communicate that Cambridge wants to see ZERO car crashes that result in fatalities or serious bodily harm for those walking and biking in Cambridge. The audience is all who use Cambridge streets, including but not limited to drivers, with the recognition that those who will benefit will most likely be pedestrians and bicyclists. 3. Deliver a toolbox of baseline ideas, as well as creative ones, to deliver this message. 4. Develop a set of recommended media partners to approach or to deliver an ad campaign 5. -

Amateur Sports Baseball

8 THE WASHINGTON HERALD r f1- Freemans Wild Heave w ame I i an BASEBALL Loses for Nationals YALE from University of Virginia AMATEUR SPORTS LOSE IN TilE NINTH YALE TRIMS VIRGINIA ACTING PRESIDENT HEYDLER TURNS DOWN CINCINNATI REDS PROTEST Murphys Clout and Free Southerners Outhit the New Another Good Acting President Hcydler of the National League gave his rul1n Shoe Snap Tnaiis Heave Responsible yesterday on the recent CincinnntlPIttsburjj game which was won by Haven Team Plttsliur and iThlch Mnnnjier Griffith protested Cfrlfflths protest tvos made on the grounds that Hans Wagner Jumped For Wideawake Men S JOHNSON IN GREAT FORM from one side oftlie plnfe < o the other irhilc the Reds pitcher iras in the SUIT WIELDS THE WILLOW set of delivering the ball His contention was that according to the rules Wagner should have been declared out 3Ir Heydlcr disallimx the protest and Rives his reasons ax follows Swell 3 50 Idaho Phenom Pitches Well and 3Ialcer Longest Hit of the Day So Patent The Cincinnati club bases Its protest In the claim that Wagner vlo- MJ Should Have Gotten by With Ylc ¬ One on the Bases at the Time H S OMOKUNDRO lated SectiOH 1C of Rule 51 In stepping from one batsmans box to the sSs- tory to Is ¬ Leather Low Shoes at w Athletics Fall Hit Until other alter the pitcher lied taken his position and that he instead of be- ¬ Third Baseman Caught Stretch Fifth Ganley and Conroy Make ing called out reached first base and scored the winning run ing n Drive Into a HomerWill The man who takes all the Six of the Nationals Hits This -

Registered Starclubs

STARCLUB Registered Organisations Level 1 - REGISTERED in STARCLUB – basic information supplied Level 2 - SUBMITTED responses to all questions/drop downs Level 3 - PROVISIONAL ONLINE STATUS - unverified Level 4 - Full STARCLUB RECOGNITION Organisation Sports Council SC Level 1st Hillcrest Scout Group Scout Group Port Adelaide Enfield 3 (City of) 1st Nuriootpsa Scout Group Youth development Barossa Council 3 1st Strathalbyn Scouts Scouts Alexandrina Council 1 1st Wallaroo Scout Group Outdoor recreation and Yorke Peninsula 3 camping Council 3ballsa Basketball Charles Sturt (City of) 1 Acacia Calisthenics Club Calisthenics Mount Barker (District 2 Council of) Acacia Gold Vaulting Club Inc Equestrian Barossa Council 3 Active Fitness & Lifestyle Group Group Fitness Adelaide Hills Council 1 Adelaide Adrenaline Ice Hockey Ice Hockey West Torrens (City of) 1 Adelaide and Suburban Cricket Association Cricket Marion (City of) 2 Adelaide Archery Club Inc Archery Adelaide City Council 2 Adelaide Bangladesh Tigers Sporting & Cricket Port Adelaide Enfield 3 Recreati (City of) Adelaide Baseball Club Inc. Baseball West Torrens (City of) 2 Adelaide Boomers Korfball Club Korfball Onkaparinga (City of) 2 Adelaide Bowling Club Bowls Adelaide City Council 2 Adelaide Bushwalkers Inc Bushwalker Activities Adelaide City Council 1 Adelaide Canoe Club Canoeing Charles Sturt (City of) 2 Adelaide Cavaliers Cricket Club Cricket Adelaide City Council 1 Adelaide City Council Club development Adelaide City Council 1 Adelaide City Football Club Football (Soccer) Port -

Relocation Guide ABOUT PIVACH PROPERTIES 01

AUSTIN NEIGHBORHOODS AUSTIN, TEXAS Relocation Guide ABOUT PIVACH PROPERTIES 01 Table of Contents 02 Dear Future Neighbors 05 Relocation Approach Sample Buyer Questionnaire 13 Austin Neighborhoods Builders Schools 32 Things to Do Music & Events Sports & Activities 38 Meet the Team Welcome To Austin To Welcome 02 ABOUT PIVACH PROPERTIES ABOUT PIVACH PROPERTIES 03 Dear "Future" Neighbors, 14 years ago, I was in your shoes. I decided to pick up my life, and venture to the lone star state to discover what all the fuss was about in Austin, Texas. These many years later, I can honestly say it was one of the best decisions I have ever made. That being said, there were still challenges to overcome as a “new” Austinite. I didn’t know what areas of town were the best fit for my wife and I to establish our roots. I really didn’t know anyone in Austin before I moved here, so relying on others’ opinions wasn’t much of an option. Through some luck (and a few bumps in the road) I eventually found my perfect spot. Over the years, I’ve found myself working more and more with people taking that same leap of faith I did. I enjoy helping others find their own place here in Austin so much, that relocation consulting became the centerpiece of my business when I founded my own company in 2012. Since then, I have had the privilege of helping dozens of individuals and families settle into our city and locate the right home to begin their own Austin story. -

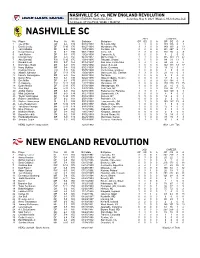

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Liv E Auction Live Auction

Live Auction 101 Boston Celtics “Travel with the Team” VIP Experience $10,000 This is the chance of a lifetime to travel with the Boston Celtics and see them on the road as a Celtics VIP! You and a guest will fly with the Boston Celtics Live Auction Live on their private charter plane on Friday, January 5, 2018 to watch them battle the Brooklyn Nets on Saturday, January 6, 2018. Your VIP experience includes first-class accommodations at the team hotel, two premium seats to the game at the Barclays Center—and some extra special surprises! Travel must take place January 5-6, 2018. At least one guest must be 21 or older. Compliments of The Boston Celtics Shamrock Foundation 102 The Ultimate Fenway Concert Experience $600 You and three friends will truly feel like VIPs at the concert of your choice in 2018 at Fenway Park! Before the show, enjoy dinner in the exclusive EMC Club at Fenway Park. Then, you’ll head down onto the historic ball park’s field to take in the concert from four turf seats. Also includes VIP parking for one car. Although the full concert schedule for 2018 is yet to be announced, the Foo Fighters “Concrete and Gold Tour” plays at Fenway Park on July 21 and 22, 2018. Past performers have included Billy Joel, James Taylor, Lady Gaga and Pearl Jam. Valid for 2018 only and must be scheduled for a mutually agreeable date. Compliments of the Boston Red Sox 103 Street Hockey with Patrice Bergeron and Brad Marchand $5,000 Give your favorite young hockey stars a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to play with the best—NHL All-Stars and Boston Bruins forwards, Patrice Bergeron and Brad Marchand! Your child and 19 friends will play a 60-minute game of street hockey with Bergeron and Marchand at your house. -

2017 Jcsu Football Media Guide Table of Contents Media Information Newspaper Radio 1

2017 JCSU FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION NEWSPAPER RADIO 1............................Table of Contents/Media Information Charlotte Observer WGNC AM 1450AM/100.1 FM 2..............................................Head Coach Kermit Blount 600 S. Tryon St. Scott Neisler 3.........................................................2017 Season Preview Charlotte, N.C. 28202 405 Neisler Dr. 704-358-5125 Kings Mountain, N.C. 28086 4.....................................................................2017 Schedule [email protected] 704-460-6049 5-9.............................................................2017 Opponents [email protected] 10..............................................................Preseason Roster Charlotte Post www.wgnc.net 11-14.............................................................2016 Statistics Herb White 15-24.....................................................2016 Game Recaps 1531 Camden Rd. TELEVISION Charlotte, N.C. 28202 WSOC 25-29.......................................Year by Year/Series Results 704-376-0496 30-34......................................Series Results by Opponent Phil Orban [email protected] 1901 N. Tryon St. 35..............................................................................Records Charlotte, N.C. 28206 36-37...........All-CIAA Selections, All-Rookie Selections Salisbury Post 704-335-4746 38..............................................................JCSU in the Pro’s Dennis Davidson [email protected] 131 W. Innes St. 39.................................................Commemorative -

Teamup AUDL Power Rankings 6/22/21

TeamUp Fantasy AUDL Power Rankings (6/24 - 6/30) https://www.teamupfantasy.com/ 1. New York Empire The Empire are still in the number one spot this week. Last weekend they had a game against the Thunderbirds and won easily. They should get another win against the Cannons next week. A real test for the Empire will be in two weeks, when they face the Breeze. 2. Chicago Union Chicago had a great weekend; they beat the Mechanix 30-13 and advanced to 3-0 on the season. Danny Miller played extremely well for them and earned player of the game from the Union. Their next game is against the AlleyCats, who have only beaten the Mechanix this year. 3. DC Breeze The game last weekend for the Breeze was amazing. Their offense and defense both had completion percentages above 90. Young players such as Jacques Nissen and Duncan Fitzgerald stepped up and played well. A.J. Merriman had a huge performance with 3 blocks and 6 scores. They are moving up a spot this week. 4. Raleigh Flyers The Flyers are moving down a spot this week, but that is only because the Breeze played exceptionally well. The Flyers got their first win of the season last weekend and have an easier schedule on the horizon. The next three games they play should be easy wins. 5. Dallas Roughnecks Dallas is staying in the same spot this week. They have only played two games and are currently 1-1. Even though they have only played two games, they did beat a good Aviators team this week. -

All Star Baseball Roster & Streaming Information

Virginia Amateur Sports, INC 711 5th Street NE, Suite C Roanoke, Virginia 24016 Telephone: (540) 343-0987 ---------------- www.CommonwealthGames.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Date: July 15, 2020 Contact: Charity E. Waldron Director of Operations & Media Relations [email protected] (434) 515-0549 - direct Virginia Commonwealth Games All Star Baseball Rosters Released All Star Tournament to be held July 17-19 at Liberty University The Virginia Commonwealth Games at Liberty University, organized by Virginia Amateur Sports, has released the rosters of the All-Star Baseball regional teams. The top 15-17 year old high school players in Virginia will represent four regions of the state in an eight game playoff. College coaches and Major League scouts are invited and attend this annual showcase. Notable tournament alumni include Justin Verlander, David Wright, BJ Upton, Justin Upton, Ryan Zimmerman and others. New this year – the games on Saturday and Sunday will be Live Streamed online for free. The link for viewing is on the All Star Baseball page of our website. Team Rosters for the four regional teams (Central, East, North & West) can be found at: CommonwealthGames.org/sports-listing/baseball-allstar The Tournament kicks off on Friday with a small Opening Ceremonies at 5:45pm, then first pitch of Game 1 (West vs Central) set to take place at 6pm, with Game 2 at around 8:30pm. Detailed schedule can also be found on our website. For 31 years the Virginia Commonwealth Games have provided excellent opportunities for thousands of Virginians to develop and foster new relationships, establish new goals and personal bests, while at the same time learning teamwork, sportsmanship, as well as individual team responsibilities. -

Other Basketball Leagues

OTHER BASKETBALL LEAGUES {Appendix 2.1, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 13} Research completed as of August 1, 2012 AMERICAN BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION (ABA) LEAGUE UPDATE: For the 2011-12 season, the following teams are no longer members of the ABA: Atlanta Experience, Chi-Town Bulldogs, Columbus Riverballers, East Kentucky Energy, Eastonville Aces, Flint Fire, Hartland Heat, Indiana Diesels, Lake Michigan Admirals, Lansing Law, Louisiana United, Midwest Flames Peoria, Mobile Bat Hurricanes, Norfolk Sharks, North Texas Fresh, Northwestern Indiana Magical Stars, Nova Wonders, Orlando Kings, Panama City Dream, Rochester Razorsharks, Savannah Storm, St. Louis Pioneers, Syracuse Shockwave. Team: ABA-Canada Revolution Principal Owner: LTD Sports Inc. Team Website Arena: Home games will be hosted throughout Ontario, Canada. Team: Aberdeen Attack Principal Owner: Marcus Robinson, Hub City Sports LLC Team Website: N/A Arena: TBA © Copyright 2012, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Alaska 49ers Principal Owner: Robert Harris Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School UPDATE: Due to the success of the Alaska Quake in the 2011-12 season, the ABA announced plans to add another team in Alaska. The Alaska 49ers will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012-13 season. The 49ers will compete in the Pacific Northwest Division. Team: Alaska Quake Principal Owner: Shana Harris and Carol Taylor Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School Team: Albany Shockwave Principal Owner: Christopher Pike Team Website Arena: Albany Civic Center Facility Website UPDATE: The Albany Shockwave will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012- 13 season.