“Snap Music” and Hip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 2 Live Crew Sports Weekend 2nd II None If You Want It 2nd II None Classic 220 2Pac Changes 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac I Get Around / Keep Ya Head Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 702. Where My Girls At 7L & Esoteric The Soul Purpose A Taste Of Honey A Taste Of Honey A Tribe Called Quest Unreleased & Unleashed Above The Law Untouchable Abyssinians Best Of The Abyssinians Abyssinians Satta Adele 21. Adele 21. Admiral Bailey Punanny ADOR Let It All Hang Out African Brothers Hold Tight (colorido) Afrika Bambaataa Renegades Of Funk Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Agallah You Already Know Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Akon Konvicted Akrobatik The EP Akrobatik Absolute Value Al B. Sure Rescue Me Al Green Greatest Hits Al Johnson Back For More Alexander O´Neal Criticize Alicia Keys Fallin Remix Alicia Keys As I Am (vinil colorido) Alicia Keys A Woman´s Worth Alicia Myers You Get The Best From Me Aloe Blacc Good Things Aloe Blacc I Need A Dollar Alpha Blondy Cocody Rock Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (vinil colorido) Alton Ellis Mad Mad Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Anita Baker Rapture Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Augustus Pablo King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown Augustus Pablo In Fine Style Augustus Pablo This Is Augustus Pablo Augustus Pablo Dubbing With The Don Augustus Pablo Skanking Easy AZ Sugar Hill B.G. -

Hip Hop America Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HIP HOP AMERICA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nelson George | 256 pages | 31 May 2005 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780143035152 | English | New York, NY, United States Hip HOP America PDF Book Kool Herc -- lay the foundation of the hip-hop movement. Stylistically, southern rap relies on exuberant production and direct lyrics typically about the southern lifestyle, trends, attitudes. Hill's brilliant songwriting flourished from song to song, whether she was grappling with spirituality "Final Hour," "Forgive Them, Father" or stroking sexuality without exploiting it "Nothing Even Matters". According to a TIME magazine article, Wrangler was set to launch a collection called "Wrapid Transit," and Van Doren Rubber was putting out a special version of its Vans wrestling shoe designed especially for breaking [source: Koepp ]. Another key element that's helping spread the hip-hop word is the Internet. Late Edition East Coast. Most hip-hop historians speak of four elements of hip-hop: tagging graffiti , b-boying break dancing , emceeing MCing and rapping. Taking Hip-Hop Seriously. Related Content " ". Regardless, the Bay Area has enjoyed a measurable amount of success with their brainchild. And then, in the mid to late s, there was a resurgence in the popularity of breaking in the United States, and it has stayed within sight ever since. Depending on how old you are, when someone says "hip-hop dance," you could picture the boogaloo, locking, popping, freestyle, uprocking, floor- or downrocking, grinding, the running man, gangsta walking, krumping, the Harlem shake or chicken noodle soup. Another thing to clear up is this: If you think hip-hop and rap are synonymous, you're a little off the mark. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

Song of the Year

General Field Page 1 of 15 Category 3 - Song Of The Year 015. AMAZING 031. AYO TECHNOLOGY Category 3 Seal, songwriter (Seal) N. Hills, Curtis Jackson, Timothy Song Of The Year 016. AMBITIONS Mosley & Justin Timberlake, A Songwriter(s) Award. A song is eligible if it was Rudy Roopchan, songwriter songwriters (50 Cent Featuring Justin first released or if it first achieved prominence (Sunchasers) Timberlake & Timbaland) during the Eligibility Year. (Artist names appear in parentheses.) Singles or Tracks only. 017. AMERICAN ANTHEM 032. BABY Angie Stone & Charles Tatum, 001. THE ACTRESS Gene Scheer, songwriter (Norah Jones) songwriters; Curtis Mayfield & K. Tiffany Petrossi, songwriter (Tiffany 018. AMNESIA Norton, songwriters (Angie Stone Petrossi) Brian Lapin, Mozella & Shelly Peiken, Featuring Betty Wright) 002. AFTER HOURS songwriters (Mozella) Dennis Bell, Julia Garrison, Kim 019. AND THE RAIN 033. BACK IN JUNE José Promis, songwriter (José Promis) Outerbridge & Victor Sanchez, Buck Aaron Thomas & Gary Wayne songwriters (Infinite Embrace Zaiontz, songwriters (Jokers Wild 034. BACK IN YOUR HEAD Featuring Casey Benjamin) Band) Sara Quin & Tegan Quin, songwriters (Tegan And Sara) 003. AFTER YOU 020. ANDUHYAUN Dick Wagner, songwriter (Wensday) Jimmy Lee Young, songwriter (Jimmy 035. BARTENDER Akon Thiam & T-Pain, songwriters 004. AGAIN & AGAIN Lee Young) (T-Pain Featuring Akon) Inara George & Greg Kurstin, 021. ANGEL songwriters (The Bird And The Bee) Chris Cartier, songwriter (Chris 036. BE GOOD OR BE GONE Fionn Regan, songwriter (Fionn 005. AIN'T NO TIME Cartier) Regan) Grace Potter, songwriter (Grace Potter 022. ANGEL & The Nocturnals) Chaka Khan & James Q. Wright, 037. BE GOOD TO ME Kara DioGuardi, Niclas Molinder & 006. -

KEM.C.GUNN IK.OWENS)Kern 79

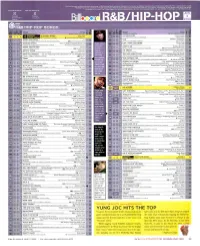

The most popular singles and tracks, acccrding to R813/110Hop iedi.4 audience impressions measured by Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems and sales datafrom a subset pane of aye RSEfil-lip-Hop stores compiled by Nie scn Souncszan.3reateSt Game, Sales and Greatest Gainer;IAErplay are awarded, respectively. tot the largest retail sales and airplay increases on the chart. Sm. Charts Lagaid for ruin od explanations. ei 2006. VNU Business Media, Inc. and Nielsen SoundScan, Inc. Allrights resene.' /JIRO TIONI-DRED lo SALES DATA COMPILED BY JUN Nelsen Nielsen 3 Snack -am P SoundSi..en 2- 2 System 41° 2006 1101. 13 &B /HIP -HOP SONGS Artist TITLE IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL e PRODUCER (SO I'M GONNA BE Donell Jones ' 1619EATE$T ITS Gm; DOWN Vung Joc 8 3 3 16 LAFACE/ZOEMIA 911.11011 pill0L9TNIT71 (IROBINSON,C.MOORE) Q BLOCK/BN) BOY SOUTH/ATLANTIC TIM a BOB (D JONES,T.KELLEY.B.ROBINSON) YOU Raheem DeVaughn WHAT YOU KNOW 8 55, 16 T.HUNTER (R.S.DEvAUGHN.T.HUNTER) 0 JIVE/20mA DJ TOOMP C.HARRIS,A.DAVIS.C.MAYEIELD,L.HUTSON,O.HATHAWAY) 00 GRAND HUSTLE/ATLANTIC ENOUGH CRYIN Mary J. Blige Featuring Brook-lyn ,{CANI TAKE YOU HOME Jamie Foxx - 3 ID Singer, wl-o ;s 0 J/RMG 411 R.JERKINS (M IBLIGE.R.JERKINS,S.GARRETT.S.C.CARTER) Co MATRIARN/GEFTEN/INTERSCOPE TIMBALAND (T.v.MOSLEY,S.GARRETT) set to opei Bubba Spanoot WHEN YOU'RE MAD Ne-Yo HEAT IT UP 59 I MR.COLLIPARK (W.mATHISN.CROOmS.S.ANDERSON) 00 NEW SOUTH/PURPLE RIBBONNIRGiN S.TAYLOR (S.SM1TH,S.TAYLOR) 00 DEE JAM/IONG for Mary Gucci Mane Featuring Mac Bre-Z GETT1N' SOME Shawnna Blige on GO AHEAD 57 5 6 $768 0 LATLARE/BIG -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: a Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’S “Mainstream” (1996)

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) MITCHELL OHRINER[1] University of Denver ABSTRACT: Recent years have seen the rise of musical corpus studies, primarily detailing harmonic tendencies of tonal music. This article extends this scholarship by addressing a new genre (rap music) and a new parameter of focus (rhythm). More specifically, I use corpus methods to investigate the relation between metric ambivalence in the instrumental parts of a rap track (i.e., the beat) and an emcee’s rap delivery (i.e., the flow). Unlike virtually every other rap track, the instrumental tracks of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) simultaneously afford hearing both a four-beat and a three-beat metric cycle. Because three-beat durations between rhymes, phrase endings, and reiterated rhythmic patterns are rare in rap music, an abundance of them within a verse of “Mainstream” suggests that an emcee highlights the three-beat cycle, especially if that emcee is not prone to such durations more generally. Through the construction of three corpora, one representative of the genre as a whole, and two that are artist specific, I show how the emcee T-Mo Goodie’s expressive practice highlights the rare three-beat affordances of the track. Submitted 2015 July 15; accepted 2015 December 15. KEYWORDS: corpus studies, rap music, flow, T-Mo Goodie, Outkast THIS article uses methods of corpus studies to address questions of creative practice in rap music, specifically how the material of the rapping voice—what emcees, hip-hop heads, and scholars call “the flow”—relates to the material of the previously recorded instrumental tracks collectively known as the beat. -

Year-End Edition 2006 Mediabase Overall Label Share 2006

MEDIABASE YEAR-END EDITION 2006 MEDIABASE OVERALL LABEL SHARE 2006 ISLAND DEF JAM TOP LABEL IN 2006 Atlantic, Interscope, Zomba, and RCA Round Out The Top Five Island Def Jam Music Group is this year’s #1 label, according to Mediabase’s annual year-end airplay recap. Led by such acts as Nickelback, Ludacris, Ne-Yo, and Rihanna, IDJMG topped all labels with a 14.1% share of the total airplay pie. Island Def Jam is the #1 label at Top 40 and Hot AC, coming in second at Rhythmic, Urban, Urban AC, Mainstream Rock, and Active Rock, and ranking at #3 at Alternative. Atlantic was second with a 12.0% share. Atlantic had huge hits from the likes of James Blunt, Sean Paul, Yung Joc, Cassie, and Rob Thomas -- who all scored huge airplay at multiple formats. Atlantic ranks #1 at Rhythmic and Urban, second at Top 40 and AC, and third at Hot AC and Mainstream Rock. Atlantic did all of this separately from sister label Lava, who actually broke the top 15 labels thanks to Gnarls Barkley and Buckcherry. Always powerful Interscope was third with 8.4%. Interscope was #1 at Alternative, second at Top 40 and Triple A, and fifth at Rhythmic. Interscope was led byAll-American Rejects, Black Eyed Peas, Fergie, and Nine Inch Nails. Zomba posted a very strong fourth place showing. The label group garnered an 8.0% market share, with massive hits from Justin Timberlake, Three Days Grace, Tool and Chris Brown, along with the year’s #1 Urban AC hit from Anthony Hamilton.