The Effect of Landuse and Geology on Macroinverterbate Communities in East Coast Streams, Gisborne, New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday, March 11, 2021 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI THURSDAY, MARCH 11, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 PAGE 3 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT PAGES 23-26 POLICE GISBORNE ACCUSED OF GALLERY ‘RACIALLY CLOSING PROFILING’ ITS DOORS PAGE 10 KIDS INSIDE TODAY CRUISING BACK TO GISBORNE: Eastland Port has 23 cruise ship visits scheduled for next summer, depending on the reopening of New Zealand borders. The Oosterdam (pictured) was a regular visitor to Gisborne in the early years of cruise ship visits here and she will be back twice in early December and early February next summer if the borders reopen. STORY ON PAGE 3 File picture A WOMAN who blew the whistle on Enterprises Limited (BEL) by his Matawai farmer John Bracken’s alleged Gisborne accountant, who unwittingly $17.4 million tax scam has given evidence prepared them using bank transactions in his High Court trial at Gisborne. manipulated by Bracken and false GST Ex-lover a She claimed Bracken was her lover, invoices he submitted. that they lived together in Auckland Bracken’s pleas to the charges have when he was regularly there for been deemed not guilty because he his export business and that she refuses to enter any. He says the charges unknowingly helped him with his scam are not his to answer — that as a by surreptitiously producing false beneficiary of a Maori Incorporation, he is invoices. protected under Te Ture Whenua Maori Bracken did not dispute their Act 1993. woman involvement but in cross-examination of Bracken is representing himself but her conveyed a situation in which she has literacy problems, so is being assisted was a woman scorned who squealed to by his wife and a McKenzie Friend the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) because of (someone who attends court in support her unfulfilled romantic designs on him. -

New Zealand Gazette

1025 "r THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, APRIL 9, 1925. RRATUM.-In the Order in Counoil dated the 19th day I Additional Land taken for the Kawalcawa-Hokianga Railway E of January, 1920, and published in the New Zealand (Okaihau Bectinn) and for Road·diversions in connection Gazette No.4, page 161, of the 23rd day of January, 1925, therewith. declaring portion of Glenora Road, in the Akitio County, to be a county TOad, read "oounty road" in lieu of " Govern· ment road" in the ninth line of the said Order in Council. [L.S.) CHARLES FERGUSSON, Governor.General. A PROCLAMATION. N pursuance and exercise of the powers and authorities Ot"OW1t. Land Bet 68ide a8 a. ProviBional State ForeBt. I vested in me by the Public Works Act, 1908, and of every other power and authority in anywise enabling me in [L.S.] CHARLES FERGUSSON, Governor·Generai. this behalf, I, General Sir Charles Fergusson, Baronet, Go. A PROCLAMaTION. vernor·General of the Dominion of New Zealand, do hereby proclaim and deolare that the additional land mentioned in the B-y virtue and in exeroise of the powers and authorities Schedule hereto is hereby taken for the Kawakawa-Hokianga conferred upon me by scotion eighteen of the Forests Railway (Okaihau Seotion) and for road· diversions in con· A~t, 1921-22, I, General Sir Charles Fergusson, Baronet, nection therewith. Governor·Generai of the Dominion of New Zealand, aoting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council of the said Dominion, do hereby set apart the Crowp. -

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

Proposed Gisborne Regional Freshwater Plan

Contents Part A: Introduction and Definitions Schedule 9: Aquifers in the Gisborne Region 161 Section 1: Introduction and How the Plan Works 3 Schedule 10: Culvert Construction Guidelines for Council Administered Drainage Areas 162 Section 2: Definitions 5 Schedule 11: Requirements of Farm Environment Plans 164 Part B: Regional Policy Statement for Freshwater Schedule 12: Bore Construction Requirements 166 Section 3: Regional Policy Statement For Freshwater 31 Schedule 13: Irrigation Management Plan Requirements 174 Part C: Regional Freshwater Plan Schedule 14: Clearances, Setbacks and Maximum Slope Gradients for Installation Section 4: Water Quantity and Allocation 42 of Disposal Systems 175 Section 5: Water Quality and Discharges to Water and Land 48 Schedule 15: Wastewater Flow Allowances 177 Section 6: Activities in the Beds of Rivers and Lakes 83 Schedule 16: Unreticulated Wasterwater Treatment, Storage and Disposal Systems 181 Section 7: Riparian Margins, Wetlands 100 Schedule 17: Wetland Management Plans 182 Part D: Regional Schedules Schedule 18: Requirements for AEE for Emergency Wastewater Overflows 183 Schedule 1: Aquatic Ecosystem Waterbodies 109 Schedule 19: Guidance for Resource Consent Applications 185 1 Schedule 2: Migrating and Spawning Habitats of Native Fish 124 Part E: Catchment Plans Proposed Schedule 3: Regionally Significant Wetlands 126 General Catchment Plans 190 Schedule 4: Outstanding Waterbodies 128 Waipaoa Catchment Plan 192 Gisborne Schedule 5: Significant Recreation Areas 130 Appendix - Maps for the Regional Freshwater Plan Schedule 6: Watercourses in Land Drainage Areas with Ecological Values 133 Regional Appendix - Maps for the Regional Freshwater Plan 218 Schedule 7: Protected Watercourses 134 Freshwater Schedule 8: Marine Areas of Coastal Significance as Defined in the Coastal Environment Plan 160 Plan Part A: Introduction and Definitions 2 Section 1: Introduction and How the Plan Works 1.0 Introduction and How the Plan Works Part A is comprised of the introduction, how the plan works and definitions. -

East Coast Inquiry District: an Overview of Crown-Maori Relations 1840-1986

OFFICIAL Wai 900, A14 WAI 900 East Coast Inquiry District: An Overview of Crown- Maori Relations 1840-1986 A Scoping Report Commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal Wendy Hart November 2007 Contents Tables...................................................................................................................................................................5 Maps ....................................................................................................................................................................5 Images..................................................................................................................................................................5 Preface.................................................................................................................................................................6 The Author.......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................................ 6 Note regarding style........................................................................................................................................... 6 Abbreviations...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One: Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand

A supplementary finding-aid to the archives relating to Maori Schools held in the Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand MAORI SCHOOL RECORDS, 1879-1969 Archives New Zealand Auckland holds records relating to approximately 449 Maori Schools, which were transferred by the Department of Education. These schools cover the whole of New Zealand. In 1969 the Maori Schools were integrated into the State System. Since then some of the former Maori schools have transferred their records to Archives New Zealand Auckland. Building and Site Files (series 1001) For most schools we hold a Building and Site file. These usually give information on: • the acquisition of land, specifications for the school or teacher’s residence, sometimes a plan. • letters and petitions to the Education Department requesting a school, providing lists of families’ names and ages of children in the local community who would attend a school. (Sometimes the school was never built, or it was some years before the Department agreed to the establishment of a school in the area). The files may also contain other information such as: • initial Inspector’s reports on the pupils and the teacher, and standard of buildings and grounds; • correspondence from the teachers, Education Department and members of the school committee or community; • pre-1920 lists of students’ names may be included. There are no Building and Site files for Church/private Maori schools as those organisations usually erected, paid for and maintained the buildings themselves. Admission Registers (series 1004) provide details such as: - Name of pupil - Date enrolled - Date of birth - Name of parent or guardian - Address - Previous school attended - Years/classes attended - Last date of attendance - Next school or destination Attendance Returns (series 1001 and 1006) provide: - Name of pupil - Age in years and months - Sometimes number of days attended at time of Return Log Books (series 1003) Written by the Head Teacher/Sole Teacher this daily diary includes important events and various activities held at the school. -

New Zealand 16 East Coast Chapter

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd The East Coast Why Go? East Cape .....................334 New Zealand is known for its mix of wildly divergent land- Pacifi c Coast Hwy ........334 scapes, but in this region it’s the sociological contours that Gisborne .......................338 are most pronounced. From the earthy settlements of the Te Urewera East Cape to Havelock North’s wine-soaked streets, there’s a National Park................344 full spectrum of NZ life. Hawke’s Bay ................. 347 Maori culture is never more visible than on the East Coast. Exquisitely carved marae (meeting house complexes) Napier ...........................348 dot the landscape, and while the locals may not be wearing Hastings & Around .......356 fl ax skirts and swinging poii (fl ax balls on strings) like they Cape Kidnappers ......... 361 do for the tourists in Rotorua, you can be assured that te reo Central Hawke’s Bay ......362 and tikangaa (the language and customs) are alive and well. Kaweka & Intrepid types will have no trouble losing the tourist Ruahine Ranges ...........363 hordes – along the Pacifi c Coast Hwy, through rural back roads, on remote beaches, or in the mystical wilderness of Te Urewera National Park. When the call of the wild gives way to caff eine with- Best Outdoors drawal, a fi x will quickly be found in the urban centres of » Cape Kidnappers (p 361 ) Gisborne and Napier. You’ll also fi nd plenty of wine, as the » Cooks Cove Walkway region strains under the weight of grapes. From kaimoana (p 338 ) (seafood) to berry fruit and beyond, there are riches here for everyone. -

Te Runanga O Ngati Porou NATI LINK October 2000 ISSUE 14

Te Runanga o Ngati Porou NATI LINK October 2000 ISSUE 14 The launch of the Tuhono Whanau/ Family Start programme at Hamoterangi House provided a strong message to the several hundred people attending – affirm your whanau, affirm your family. Pictured from left are kaiawhina Sonia Ross Jones, Min Love, Makahuri Thatcher, whanau/hapu development manager Agnes Walker, Runanga chief executive Amohaere Houkamau, Tuhono Whanau manager Peggy White, kaiawhina Phileppia Watene, supervisor Waimaria Houia, kaiawhina Heni Boyd- Kopua (kneeling) and administrator Bobby Reedy. See story page five. Coast is ‘best kept’ tourism secret Runanga CEO Amohaere Houkamau Porou tourist operators achieve maximum images were to have been used as one of the top launched the Tourism Ngati Porou strategic exposure. 16 tourist attractions promoted by the Tourism plan earlier this month, but not before The network will also work with regional Board internationally. explaining the area was the “best kept tourism tourism organisations and help co-ordinate and “Culturally-based tourism can provide secret in New Zealand”. promote Ngati Porou tourism initiatives. employment for each hapu. She believes the area’s natural features — “The strategy is to pool our skills, to work “The key principle is to support Ngati Porou Hikurangi Maunga, secluded bays, native collaboratively, limit competition and ensure tourism, with limited resources, we have to bush, surf-beaches, historical attractions such that in the process we do not compromise our support ourselves. as the Paikea Trail and significant art works culture. “Our experience in the past has been that including the Maui Whakairo and carved “We must also ensure that our intellectual people have taken a lot from Ngati Porou in meeting-houses — are major attractions. -

O Ngati Porou I SUE 41 HEPE EMA 011 NGAKOHINGA

ISSUE 41 – HEPETEMA 2011 o Ngati Porou I SUE 41 HEPE EMA 011 NGAKOHINGA o Ngati Porou Cover: Naphanual Falwasser contemplates the Editorial winter wonderland at Ihungia. (Photo by Keith Baldwin) Tena tatou Ngati Porou. Tena tatou i o tatou mate huhua e whakangaro atu nei ki te po. Kei te tangi atu ki te pou o Te Ataarangi, ki a Kahurangi Dr Katerina Mataira me te tokomaha o ratou kua huri ki tua o te arai. Haere atu koutou. Tatou nga waihotanga iho o ratou ma, tena tatou. Change is certainly in the air. The days are getting warmer and longer. Certainly nothing like the cold snap a couple of Contents weeks ago that turned Ruatoria in to a “Winter Wonderland”. We are hoping the torrential rains which caused a flooded 1 Uawa Rugby Ruckus Kopuaroa river to wash out the bailey bridge at Makarika, 2-5 Te Ara o Kopu ki Uawa are also gone. Spring signals new life and new beginnings 6 Kopuaroa Bridge Washout and it, appropriately so, coincides with the inaugural elections for our new iwi authority, Te Runanganui o Ngati 8 “Ka rukuruku a Te Rangitawaea i ona Pueru e” Porou. In this issue we farewell a Dame and we meet a 10 Building a Bridge For Apopo Diplomat. Dame Dr Katerina Te Heikoko Mataira was a 12-13 Ngati Porou We Need Your Help! soldier of te reo Maori who lost her battle with cancer in July. 14-19 Radio Ngati Porou She is an inspiration for Ngati Porou women like the Deputy High Commissioner of South Africa, Georgina Roberts. -

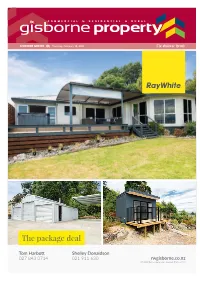

Property Guide, July 15, 2021

Thursday, July 15, 2021 2 3 4 5 71 CHALMERS ROAD TE HAPARA tender Closes: 12noon Wednesday 4th August 2021 the family favourite (unless sold prior) VIEWING: Sunday 11am – 11:30am 120m² 1323m² 3 2 Stop the search,call the bank, sort the Kiwisaver – I have found the home you’ve been waiting for. Whether it’s a super-sized section you’re after, the outlook over to the golf course, the close proximity to schools, or the hop, skip and a jump over to Rugby Park… families will absolutely love this one. Here’s all you want to know: • Built in the 1970’s – easy peasy insurance compliance right here; • Heat-pump, insulated ceilings and underfl oor; • Super spacious 120m2 in fl oorsize with generous living areas; • Modifi cation of the original garage makes for an awesome • Heaps of storage, all three bedrooms have inbuilt dressers and double wardrobes; outdoor he/she or teen cave (with w/c) or convert back; • Positioned perfectly to enjoy awesome afternoon sun; • The section – it’s a whopping 1323m2! Your winter pool project is just waiting here to be spruced up for the coming summer months. AND, being for sale by tender means conditional off ers are welcome – YAY for you. No waiting to move in either, with new plans locked and loaded, settlement date can be much sooner than later. P 06 929 1933 | M 027 553 5360 | E [email protected] | W www.tracyrealestate.co.nz 121 Ormond Road, Gisborne Tracy Bristowe, AREINZ | Licensed Real Estate Agent REA 2008 6 Te Karaka 10 Kipling Road Final Notice Time to change your pace? Thinking you need a change and want to be part of an awesome rural community? Are you trying to break into the housing Auction 3.00pm, Thu 22nd Jul, 2021, (unless sold prior), 66 Reads market or perhaps you are looking for something to get your teeth stuck into – well do I have the perfect property for you! Quay, Gisborne View Sat 17 Jul 12.00 - 12.30pm Located just a 20 minute drive from Gisborne you will find this 1000 sqm property. -

Property Guide, February 18, 2021

Thursday, February 18, 2021 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 108A ORMOND ROAD WHATAUPOKO a sunny gem 90m² 455m² 2+ 1 1 What a fabulous property, there is just so much to love about 108A Ormond Road, Whataupoko; there is something for everyone with this sweetie. LAST CHANCE • LOCATION: close to Ballance • JUST EASY: a pocket-size section that St Village with all the day to day packs a lot of punch. A manageable conveniences you may need – a super 455m2, with dual parking options given handy convenient location; the corner site. Nicely fenced, some • A LITTLE RETRO: a classic 1950s. Solid gardens in place, and fully fenced out structure, native timberwork and hardy back for your precious pets, or little weatherboard exterior. Good size ones; lounge, and kitchen/dining, and, both • EXTRAS: a shed for ‘tinkering’, and an bedrooms are double. Lovely as is, but outdoor studio for guests, hobbies, or with room to add value; maybe working from home? And Investors, if you are looking for a rock-solid property with IMPECCABLE tenants – get this one to the top of your list. tender Closes: 12pm Tuesday 23rd February 2021 (unless sold prior) VIEWING: Saturday 1pm-1:30pm Or call Tracy to view 70 ORMOND ROAD WHATAUPOKO it’s the location… 152m² 522m² 4 1+ 1 As a buyer you know it’s all about LOCATION & OPPORTUNITY, and they say “buy the worst house in the best street” to get ahead in the property game. LAST CHANCE To be fair, potentially not the ‘worst house’ but definitely one that piques the curiosity; and it’s located in a ‘best street’ a fabulous part of Gisborne – WHATAUPOKO. -

Mana Moana Guide to Nga Hapu O Ngati Porou Deed to Amend Double Page Booklet.Pdf

Mana Moana Nga Hapu o Ngati Porou Foreshore and Seabed Deed of Agreement A guide to understanding the process to ratify amendments to the Deed “Ko taku upoko ki tuawhenua Contents Ko aku matimati ki tai” “My head shall face landwards Foreword 4 and my feet shall point seawards” Navigating the Guide 5 Rerekohu PART ONE INTRODUCTION 7 Background to Nga Hapu o Ngati Porou Foreshore & Seabed journey 8 Key milestones along the journey 10 PART TWO SUMMARY OF AMENDED DEED OF AGREEMENT 13 Approach to the Amendments 14 Approach to the Principles 14 Recognition of Mana 14 Amendments to Align with the 2011 Act 15 Instruments and Mechanisms 16 Additional Recognition and Protection in CMT Areas 18 Additional Amendments 19 Management Arrangements 20 PART THREE THE RATIFICATION PROCESS 23 Summary of Ratification Process 24 Information Hui 24 Ratification Hui 24 Ratification Resolutions 24 PART FOUR WHAT HAPPENS AFTER RATIFICATION? 27 What Will Happen Next? 28 Further Information 28 Kupu Mana Moana 30 Published by: Te Runanganui o Ngati Porou, 2016 Cover Image: Whangaokeno, as seen from Tapuarata Beach, Te Pakihi (East Cape). This page: Whangaokeno as seen from Rangitukia. Photo Credits: All photographs copyright of Te Runanganui o Ngati Porou (except for image on pg 15). Whareponga looking over to Waipiro image (pg.15) courtesy of Walton Walker. 2 Mana Moana Mana Moana 3 East Cape Lighthouse on Otiki Hill, Te Pakihi. Foreword Tena tatau Ngati Porou, otira nga karangaranga hapu mai rano e pupuri i te mana o nga takutaimoana mai i Potikirua ki te Toka a Taiau.