Department of Defense Authorization for Appropriations for Fiscal Year 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TQL in the FLEET: from Theory to Practice''

AD-A27544 EuUU~flhTQLO Publication No. 93-05 Otbr 1993 TQL IN THE FLEET: From Theory to Practice'' AW Judy Was ik Navy Personnel Research and Development Center and Bobbie Ryan Total Quality Leadership Office 94-.04214 L 2611 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 2000, Arlington, VA 22202-4016 ABOUT THE TQL OFFICE The Total Quality Leadership (1QL) Office is a members serve as consultants and facitators to part of the Office of the Under Secretay of the selected groups undertaking strategic planning. Navy. Its mission is to provide technical guidance to Navy and Marine Corps senior leaders on the NETWORKING consistency between Department of the Navy tool for itthoving (DON) policy and TQL principles and practices. processes.Benchmarking Recently, is a valuable in conjunction with the Na- The TQL Office works on quality improvement tional Aeronautics and Space Administration and efforts with many organizations inside and outside with the Internal Revenue Service, the TQL Office the Federal Government. The director and mem- financed a one-time initiation fee required to join bers of the TQL Office staff recently participated the International Benchmarking Clearinghouse on the Vice President's National Performance Re- (IBC) established by the American Productivity view (NPR) team. The Office is also a key player and Quality Center. As a result of this funding, all in an NPR follow-up effort called the Defense Federal agencies can now participate in IBC serv- Performance Review (DPR). The DPR team ices without paying individual initiation fees. tasked the DON to take the lead in developing and implementing a total quality in defense manage- The TQL Office also sponsored four people from ment prototype in the Department of Defense. -

US Navy Program Guide 2012

U.S. NAVY PROGRAM GUIDE 2012 U.S. NAVY PROGRAM GUIDE 2012 FOREWORD The U.S. Navy is the world’s preeminent cal change continues in the Arab world. Nations like Iran maritime force. Our fleet operates forward every day, and North Korea continue to pursue nuclear capabilities, providing America offshore options to deter conflict and while rising powers are rapidly modernizing their militar- advance our national interests in an era of uncertainty. ies and investing in capabilities to deny freedom of action As it has for more than 200 years, our Navy remains ready on the sea, in the air and in cyberspace. To ensure we are for today’s challenges. Our fleet continues to deliver cred- prepared to meet our missions, I will continue to focus on ible capability for deterrence, sea control, and power pro- my three main priorities: 1) Remain ready to meet current jection to prevent and contain conflict and to fight and challenges, today; 2) Build a relevant and capable future win our nation’s wars. We protect the interconnected sys- force; and 3) Enable and support our Sailors, Navy Civil- tems of trade, information, and security that enable our ians, and their Families. Most importantly, we will ensure nation’s economic prosperity while ensuring operational we do not create a “hollow force” unable to do the mission access for the Joint force to the maritime domain and the due to shortfalls in maintenance, personnel, or training. littorals. These are fiscally challenging times. We will pursue these Our Navy is integral to combat, counter-terrorism, and priorities effectively and efficiently, innovating to maxi- crisis response. -

The Evolution of the US Navy Into an Effective

The Evolution of the U.S. Navy into an Effective Night-Fighting Force During the Solomon Islands Campaign, 1942 - 1943 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jeff T. Reardon August 2008 © 2008 Jeff T. Reardon All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation titled The Evolution of the U.S. Navy into an Effective Night-Fighting Force During the Solomon Islands Campaign, 1942 - 1943 by JEFF T. REARDON has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Marvin E. Fletcher Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences iii ABSTRACT REARDON, JEFF T., Ph.D., August 2008, History The Evolution of the U.S. Navy into an Effective Night-Fighting Force During the Solomon Islands Campaign, 1942-1943 (373 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Marvin E. Fletcher On the night of August 8-9, 1942, American naval forces supporting the amphibious landings at Guadalcanal and Tulagi Islands suffered a humiliating defeat in a nighttime clash against the Imperial Japanese Navy. This was, and remains today, the U.S. Navy’s worst defeat at sea. However, unlike America’s ground and air forces, which began inflicting disproportionate losses against their Japanese counterparts at the outset of the Solomon Islands campaign in August 1942, the navy was slow to achieve similar success. The reason the U.S. Navy took so long to achieve proficiency in ship-to-ship combat was due to the fact that it had not adequately prepared itself to fight at night. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

Key US Aircraft and Ships for Strikes on Iraq

CSIS_______________________________ Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 775-3270 Key US Aircraft and Ships for Strikes on Iraq Anthony H. Cordesman CSIS Middle East Dynamic Net Assessment February 16, 1998 Copyright Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. Key US Ships and Aircraft for Strikes on Iraq 3/2/98 Page 2 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................... 2 F-15 EAGLE ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................. 5 F-16 FIGHTING FALCON................................................................................................................................. 7 FEATURES.......................................................................................................................................................... 7 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................................... 7 B-1B LANCER..................................................................................................................................................... 9 MISSION............................................................................................................................................................. -

Gifts from Squadron for Everyone on Santa's Nice List!

December 2017 BRINGING HISTORY TO LIFE Kits & Accessories Gifts from Squadron for Everyone on Santa’s BooksBooBooooks & MagazinesM g Nice List! ToolsToo & PaintsP CollectiblesC tibl & AApparell Merry Christmas From All of Us Here at Squadron! SeeS bback cover for full details. OrderO Today at WWW.SQUADRON.COM or call 1-877-414-0434 DearDDearF FFriendsriei ndsd Do I love Christmas? You betcha I do! Ever since I can remember, Christmas was always the biggest day of the year for me. Still is actually, but now I’m more focused on celebrating the holiday rather than sniffing around the tree to see if there is something that has the size and shape of a model kit! Here at Squadron, the holidays are the busiest time of the year and we’re trying to do our best to end the year the way we started it and that is with a great group of new products sure to excite all of you. We are thrilled to introduce our new line of display bases for your models. Nothing finishes telling the story of the kit you have built than a proper display. Check out pages 8-9 to learn all about these new display bases exclusively available at Squadron. Featuring one of these new display bases is a very limited-edition Encore Kit of the Blue Max Pfalz (EC32004SE on the back cover). There are only 300 pieces available of this great kit! Act fast as these are sure to be gone very quickly. There are 3 NEW True Details Premium wheel sets available for the F-18C Hornet. -

The Navy Vol 61 Part 1 1999

JANUARY-MARCH 1999 VOLUME 61 NO. 1 The Magazine of the Navy League of Australia THE NAVY Viewpoint Like all quality magazines. The Navy must change with Volume 61 No 1 the times. As the millennium approaches and to mark the beginning of the its seventh decade of publication our presentation has been altered to meet the needs of its Feature Articles readers. 3 World Navies Build New Generations The Navy is now broadly presented via the major or of Surface Combatants feature articles, naval happenings, smaller supporting 5 Nuke Ships Steam Into Hot Water stories and the regular features. 8 HMAS BARCOO - Grounding April 1948 From the July edition onwards, the Navy League, its 13 USS INCHON - MCS 12 members and readers, welcome to the editorship chair, 16 Naval Review - South Korea regular contributor Mark Schweikert. With the former Federal President Geoff Evans as Managing Editor. Mark 17 Naval Happenings will co-ordinate the contents of the each edition, RAN Celebrates 87 following the retirement of this writer, after 22 years and A New Future for ARDENT 88 editions. Fleet Air Arm 50th To create and maintain the quality of such a magazine, requires the continuous help of many Navy League 22 New Zealand News members, as well as readers of The Navy, it would be HMNZS RESOLUTION Survey Role impossible to name all contributors over the two decades, HMNZS CHARLES UPHAM but special mention should be made of the former Federal Right Ship for the Job? President Geoff Evans. Otto Albert from the NSW Division and Tony Grazebrook from Victoria. -

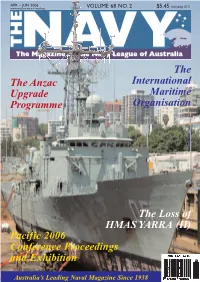

The Navy Vol 68 No 2 Apr 2006

APR – JUN 2006 (including GST) www.netspace.net.au/~navyleag VOLUME 68 NO. 2 $5.45 The The Anzac International Upgrade Maritime Programme Organisation The Loss of HMAS YARRA (II) Pacific 2006 Conference Proceedings and Exhibition Australia’s Leading Naval Magazine Since 1938 A unique image showing three generations of RAN patrol boat. From largest to smallest, HMAS ARMIDALE, HMAS TOWNSVILLE and the former HMAS ADVANCE, now part of the Australian National Maritime Museum’s collection. (Andy McKinnon) The Arleigh Burke Flight IIA class destroyer USS PICKNEY. PICKNEY was in Sydney for the Pacific 2006 Maritime Congress. She has much the same anti-air system as the RAN’s proposed air warfare destroyer, namely her SPY-1 D radar and Aegis Baseline 7.1 software. (USN) THE NAVY The Navy League of Australia FEDERAL COUNCIL Patron in Chief: President: His Excellency, The Governor General. Vice-Presidents:Graham M Harris, RFD. Volume 68 No. 2 RADM A.J. Robertson, AO, DSC, RAN (Rtd): John Bird, CDREHon. Secretary: H.J.P. Adams, AM, RAN (Rtd). CAPT H.A. Josephs, AM, RAN (Rtd) Ray Corboy, PO Box 2063, Moorabbin, Vic 3189. Contents Telephone: (03) 9598 7162, Fax: (03) 9598 7099, Mobile: 0419 872 268 NEW SOUTH WALES DIVISION TRIUMPH AND TRAGEDY, THE LOSS OF Patron: Her Excellency, The Governor of New South Wales. HMAS YARRA (II) President: Hon. Secretary:R O Albert, AO, RFD, RD. Elizabeth Sykes, GPO Box 1719, Sydney, NSW 2001 By Greg Swindon Page 4 Telephone: (02) 9232 2144, Fax: (02) 9232 8383. VICTORIA DIVISION THE INTERNATIONAL MARITIME Patron: His Excellency, The Governor of Victoria. -

ALL TIME INDEX Volumes 1-16

1935 – Basic airbrushes ALL TIME INDEX Volumes 1-16 ©2002, Kalmbach Publishing Co., 21027 Crossroads Circle, P. O. Box 1612, Waukesha, WI 53187-1612 Included in this index are articles and departments in the 1982-1998 issues of FineScale Modeler. Addtional copies of this index may be obtained by sending a large self-addressed, stamped envelope to our Customer Sales and Service Deparment at the address above. *1935 Morgan, Dec 1998 p28 Curtiss P-36, March 1994 p52 Attack Lizard, Summer 1983 p52 Honda Civic, Hasegawa, March 1996 p78 Aungst, David, A-4M Skyhawk, Sept 1997 p64 A Snapping up Ertl/AMT’s ‘93 Camaro, Jan 1994 p42 Aurelio Gimeno Ruiz’s “Star of Africa” diorama, July 1997 T-33A, Hobbycraft, March 1995 p90 p28 A-10A Ghost scheme, U.S. Air Force, July 1994 p40 Tackling Tamiya’s Triceratops, July 1994 p58 *Aurora kits that never were, Oct 1998 p50 A-10A MASK-10A schemes, Feb 1989 p56 *Amazing aircraft cutaways, May 1999 p26 *Aurora’s Albatros, Dec 1999 p71 A-4M Skyhawk conversion, Sept 1997 p64 *"American Graffiti" Deuce coupe, Nov 1999 p66 Aurora’s Batmania from the 1960s, Jan 1990 p33 A-5A Vigilante, Jan 1993 p42 Anderson, Ray Aurora’s colorful WWII 1994 fighters, WWII 1994 p26 A-6 Intruder diorama, Nov 1992 p26 Art of the diorama, Choosing a subject for a scene that Aurora’s Creature of the Black Lagoon, Sept 1996 p66 A6M2 Zero, July 1992 p22 tells a story, April 1987 p22 Aurora’s Dick Tracy Space Coupe, March 1997 p58 *A-36: Mustang dive bomber, Dec 1999 p36 Art of the diorama, Designing boxed scenes, June 1987 p50 Aurora’s F-9F