IBSROWN Memorial Lecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caribbean State Posture, Merchant Capital and the Export Services Option

Third World Quarterly, Vol 23, No 4, pp 725–751, 2002 At whose service? Caribbean state posture, merchant capital and the export services option DON D MARSHALL ABSTRACT Elite planners in the Eastern Caribbean sub-region pin their hopes of economic viability on tourism, a vibrant offshore financial (and other) services sector and an increase in export activity from companies operating out of industrial parks. Framed against the perception of an inevitable globalisation process underway, with limitations posed to high-level or diversified manu- facturing, power holders have sought to concentrate on the promotion of ‘export services’ as a viable cover against new competitive challenges. This article argues, however, that this state of affairs betrays a crisis-of-mission within the ruling class on how to reconstruct political economies marked by the hegemony of merchant capital. Rather than a move towards what are globally the most remunerative factors of production—high-level manufacturing and services—a rather curious consensus has emerged which proclaims a solid future for export services without roots and/or ganglia to local manufacturing. The success of such an ‘export services’ model anywhere in the Eastern Caribbean will not turn as much on the quality of human resources as it will on overcoming the short- term horizon of local politicians, and the low-risk predilections of the wealthy planter–merchant elite. The latter’s conscious ‘opt out’ strategy on the question of manufacturing diversity has made for a strikingly conservative enterprise culture. More specifically, merchant capitalist societies like those in the Eastern Caribbean insufficiently display the sociocultural attributes required for the creation of high-level services: innovation-mediated risk, research and develop- ment competence, and affinities to industrial processes and networks. -

Barbados Advocate

Established October 1895 See inside Monday March 22, 2021 $1 VAT Inclusive NUPW MAKING STRIDES DURING PANDEMIC PRESIDENT of the National McDowall told those in atten- The NUPW head also re- we continue to work on for our care that we will be able to push Union of Public Workers dance, “We vigorously negoti- vealed that there is now a pol- members. past this moment in our his- (NUPW), Akanni McDowall ated with government to ensure icy put forward by the union “We remain firm in our re- tory... I wish to reiterate that says the union has accom- that the BOSS program was that provides the framework for solve to fight injustices perpe- we remain focused as an objec- plished a lot, even more so voluntary and not forced as flexible working arrangements trated against our membership. tive of representing the inter- in the context of the pan- originally proposed. We have and working from at home. Because quality representation ests of our membership.” demic. been able to make some head- “High on the agenda moving for our workers is our goal, and He gave the assurance that He was delivering brief re- way in improving the lives of forward is a discussion about delivering equality for all is our as the NUPW enters its 76th marks at the St. George Parish public servants by ensuring our altering the senior public serv- defining purpose as a union.We year, it will continue to grow church yesterday as the NUPW public officers were appointed. ice posts and the implications must also continue to be each and adapt to meet the changing starts its week of activities to We are still in the process of ad- for public officers. -

The History of Political Independence and Its Future

The Time of Sovereignty: The History of Political Independence and its Future Dr. Richard Drayton Monday, November 28, 2016 Frank Collymore Hall Tom Adams Financial Centre It is a great honour, pleasure and privilege to give the Sir Winston Scott Memorial Lecture of the Central Bank of Barbados. It is particularly moving to me to look out at this crowd of 500 and see so many people I have known for over forty years, and in particular so many of the elders who formed me. I am conscious that my predecessors include such senior figures in the history of economics as Ernst Schumacher and the Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz and such deans of Caribbean intellectual life as Rex Nettleford and Gordon Rohlehr. I am particularly humbled, as a Barbadian, to give this 41st Lecture as part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of the independence of Barbados. (Clearly, Rihanna was unavailable). I came to this island from Guyana only as a boy of 8. So it was not from hazard of birth but mature choice that I joined you in citizenship. I take no second place to the birth right Bajan in my love for this rock in which my roots are tangled with yours for all time. Our 50th anniversary is a joyful occasion. It is at the same time as a sobering one, when one reflects on the generations of ancestors, living and dying under conditions of the most extraordinary inhumanity, who made our presence today possible. If this Golden Jubilee celebration has any meaning, we need to remember why we sought political sovereignty. -

The National Strategic Plan of Barbados 2005-2025

THE NATIONAL ANTHEM In plenty and in time of need When this fair land was young Our brave forefathers sowed the seed From which our pride is sprung, A pride that makes no wanton boast Of what it has withstood That binds our hearts from coast to coast - The pride of nationhood. Chorus: We loyal sons and daughters all Do hereby make it known These fields and hills beyond recall Are now our very own. We write our names on history’s page With expectations great, Strict guardians of our heritage, Firm craftsmen of our fate. The Lord has been the people’s guide For past three hundred years. With him still on the people’s side We have no doubts or fears. Upward and onward we shall go, Inspired, exulting, free, And greater will our nation grow In strength and unity. 1 1 The National Heroes of Barbados Bussa Sarah Ann Gill Samuel Jackman Prescod Can we invoke the courage and wisdom that inspired and guided our forefathers in order to undertake Charles Duncan O’neal the most unprecedented Clement Osbourne Payne and historic transformation in our economic, social and physical landscape since independence in Sir Hugh Springer 1966? Errol Walton Barrow Sir Frank Walcott Sir Garfield Sobers Sir Grantley Adams 2 PREPARED BY THE RESEARCH AND PLANNING UNIT ECONOMIC AFFAIRS DIVISION MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND ECONOMIC AFFAIRS GOVERNMENT HEADQUARTERS BAY STREET, ST. MICHAEL, BARBADOS TELEPHONE: (246) 436-6435 FAX: (246) 228-9330 E-MAIL: [email protected] JUNE, 2005 33 THE NATIONAL STRATEGIC PLAN OF BARBADOS 2005-2025 FOREWORD The forces of change unleashed by globalisation and the uncertainties of international politics today make it imperative for all countries to plan strategically for their future. -

Retailers Encouraged to Keep Prices Down

Established October 1895 It’s red…red…red! Monday March 16, 2020 $1 VAT Inclusive RETAILERS ENCOURAGED TO KEEP PRICES DOWN AS the COVID-19 virus spreads throughout the world, a local government minister is not only urging Barbadians not to panic, but is putting the case to retailers and wholesalers in this country not to jack up their prices. Minister of Small Business, Entrepreneurship and Commerce, Dwight Sutherland issued the appeal while speaking to The Barbados Advocate yesterday morning, on the sidelines of a service at Love and Light Ministries, which is based at the St. George Secondary School, to mark World Consumer Rights Day. Sutherland noted that while Barbados remained virus free, with the spread of the novel coronavirus in the Caribbean, persons living here have been stocking up on goods including hand sanitisers and other disinfecting products, which he ad- mitted has resulted in such items being in short supply. However, the Commerce Minister says stock is on its way and he is hopeful that no exorbitant prices will be charged when those items reach here. “We believe the way to address this is to have consultation with the With concerns growing about the novel coronavirus, the congregation at Love and Light Ministries, linked arms instead of stakeholders and involve the retailers holding hands during yesterday’s service. Here, Dwight Sutherland (right), Minister of Small Business, Entrepreneurship and suppliers. There is a tendency in the and Commerce, links arms with Co-Pastor, Kathyann Harewood. international world for people to engage in price gouging; we have not seen it here and the Barbados Chamber of Commerce protect the consumer. -

Cavehill Uwi Report 2006.Pdf

C o n t e n t s Chairman’s Statement ..............................3 Principal’s Report .....................................5 Teaching and Learning ...........................21 Research and Development ...................28 Publications ............................................31 Student News .........................................33 Administrators of the Campus ...............36 Members of Campus Council ................37 Campus Management ............................38 Financial Summary .................................41 Outreach – University and Campus .......43 Outreach – Faculties and Departments ..44 Campus Events ......................................47 Saluting Achievement .............................49 Recognition ................................................... 51 Statistics (charts) ....................................54 Benefactors ............................................64 International Visitors ...............................67 “[This] Report points to success in our efforts to open up access to larger numbers of those seeking entry to our Campus; it speaks of important expansion and innovation in programming; the provision of enhanced student amenities; improvements to the physical infrastructure and administrative procedures; and the development of a graduate studies and research agenda tailored to regional development needs.” The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus ANNUAL REPORT 2006 Chairman’s Statement The Cave Hill Campus’ Annual Report 2005-2006 In a dynamic and competitive global educational -

Cleviston Haynes: Debt Exchange

Central Bank of Barbados Tom Adams Financial Centre, Spry Street, Bridgetown P.O. Box 1016 Telephone: (246) 436-6870 : Fax. (246) 436-7836 E-Mail Address: [email protected] Website: www.centralbank.org.bb Remarks by Mr. Cleviston Haynes Governor, Central Bank of Barbados at “Debt Exchange – Risks and Opportunities: Leveraging the Jamaican Experience” Courtney Blackman Grande Salle Thursday, November 15, 2018 On behalf of the Management and staff of the Central Bank, I welcome everyone to this workshop, which is geared towards sharing insights on the functioning of the money and capital markets in the aftermath of the restructuring of Barbados’ domestic debt. I take this opportunity to thank NCB Capital Markets Barbados Limited for its willingness to share with us their experience and knowledge gained from the Jamaica Debt restructuring exercise in 2013. On June 1, 2018, the newly-elected administration announced the unprecedented decision that Barbados had decided to suspend the servicing of commercial foreign debt payments and restructure both domestic and external debt. The purpose was to limit foreign reserves outflows, while securing meaningful and gradual debt reduction, thereby reducing financing needs and restoring debt sustainability. The subsequent launch of a comprehensive domestic debt restructuring exercise on September 7 2018, as a critical component of the Barbados Economic Recovery Transformation (BERT) Programme, achieved near unanimous acceptance of the debt exchange proposals, with 97% participation by creditors. The terms of the new instruments involve some sacrifice by all bondholders, as Government seeks to balance the fiscal imperatives, including anchoring the BERT programme through a reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio to 60% by 2033, against the need to preserve financial stability and protect the long-term interests of small bondholders. -

Sixth Tom Adams Memorial Lecture, 2015

The Sixth Annual Tom Adams Memorial Lecture Title: Tactician and Strategist Extraordinaire and Transformative Prime Minister Delivered by Sir Richard Cheltenham Following is an edited version of the Sixth Tom Adams Memorial Lecture delivered by attorney-at-law and former Member of Parliament Sir Richard Cheltenham, QC, last Wednesday, March 11, at the Grande Salle, Tom Adams Financial Centre, The City, marking the 30th anniversary of former Prime Minister Adams’ passing. Tom Adams is, on any reckoning, one of the most outstanding and gifted Barbadians of our history. His contribution to party politics, the House of Assembly, the constituency of St Thomas and to the country and its governance has been large indeed. It is wholly appropriate, therefore, that his memory is being kept alive. It is commendable that for the last 30 years –– and today, too –– the constituency branch has placed a floral arrangement on his grave . It is only about ten years ago that this lecture series commenced. This evening’s lecture is the Sixth Tom Adams Memorial Lecture. They have not been annual, but they have been continuing. At the forefront of the efforts has been the Honourable Ms Cynthia Forde, the Member of Parliament for St Thomas. I want to recognize her for her untiring and enlightened efforts in regard to Tom’s memory, and for her caring and energetic service as a Member of Parliament. Sir Alexander Hoyos’ book Tom Adams: A Biography apart, much of what has been written to date relates to his role in sending Barbadian troops to St Vincent in December, 1979, to quell the disturbance at Arnos Vale. -

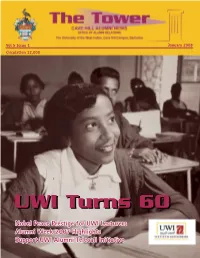

January 2008 Vol 5 Issue 1 Circulation 12,000

Vol 5 Issue 1 January 2008 Circulation 12,000 The Tower January 2008 Photograph compliments Sandy Pitt editor’s note Best wishes to the UWI alumni community for the new year! 2008 marks the diamond anniversary of the UWI. On this very special occasion, The Tower takes a look back at the early years 1948 – 1963, the year in which the Cave Hill Campus was established. The dreams, the hopes and the expectations for our University, one of the Caribbean’s truly regional institutions, are captured in the expression on the face of Sheila Sealy (neé Payne), first year Arts student in March President of UWIAA Maxine McClean Chats with alumnus Chris 1955 on our cover, reproduced with her kind Sinckler, while Roseanne Maxwell and Sonia Johnson, of the Business Development and Alumni Relations Office look on. (UWI permission. In this edition, our feature article Graduate Fair, 2007.) takes us on a journey back to those formative years of the University College of the West Indies Graduate (UCWI) through the words of Jeremy Taylor in a 1993 Caribbean Beat article and photographs Recruitment Drive provided by the Federal Archives at the Cave Hill Campus and the Mona Library. We catch a glimpse The UWI, Cave Hill Campus studies and research. We of the excitement of the dream that was UCWI held its first ever Graduate need to have at least 20% and gain a sense of the historical significance Recruitment Fair in of our students enrolled in of that fledgling institution, its survival through Barbados at the Sherbourne higher degrees, so we are the collapse of the West Indies Federation and Conference Centre on focusing on a new policy with its struggle to establish itself as the uniquely November 7, 2007. -

Issue 09, 2009

ISSUE 9 : April ‘09 Contents A PUBLICATION OF THE INFORMATION DISCOURSE CAMPUS FOCUS AND MARKETING OFFICE, 2 University will drive progress 20 Enhancing quality THE UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES, CAVE HILL CAMPUS. 21 Teaching Certificate NEWS 22 Strategies to combat We welcome your comments and 3 Walcott Warner Theatre literacy challenges feedback which can be directed to [email protected] 4 Examining the crisis 23 Cave Hill Evening or Chill c/o Marketing Office, 5 Globalisation a failure? 24 Total quality at Cave Hill UWI, Cave Hill Campus, 6 Observations on Bridgetown BB11000 Barbados economic turmoil STUDENT CENTERED Tel: (246) 417-4057 / (246) 231-8430 8 Surviving the meltdown 26 Minding your business 9 Call for UWI-led solutions 27 SEED Testimonials CO-EDITORS: Chelston Lovell 10 Taking tourism forward 28 Study in Colombia Janet Caroo 11 Contractor’s solid stance 29 On-the-job learning CONSULTANT EDITOR: on technology 30 Understanding Dyslexia Korah Belgrave 12 CIMH opens its doors 31 Jo’s Journey CONTRIBUTORS 12 Gender summer programme ARTS Prof. Sir Hilary Beckles Andrea Wharton Dr Andrea Sealy Lesley Walcott PARTNERSHIP 33 Poui milestone Bernard Babb Katheryn Stewart 13 ¡Los Venezolanos Kathy-Ann Caesar Dr Curwen Best 34 A Monument Marcia Erskine Eduardo Ali hablan íngles! for Moses Carmel Haynes Dr Anthony Fisher 14 UWI makes a creative link 35 Tribute to Colly Sonia Johnson Dr Stacy Blackman Steven R. Leslie Prof. Jane Bryce 14 Legal aid 35 Life’s like a play… Roy Morris Rhonda Walcott 36 Best on Brathwaite Kim Whitehall -

Pbl Constitutional Reform 02 Eng.Pdf

Executive Summary Chapter I: Westminster in the Caribbean: Viability Past and Present, Prospects for Reform or Radical Change A. Impetus for Change B. Governance: The Heart of the Matter C. The Crucial Role of Civil Society D. Critiquing Westminster E. The Power-Sharing Option F. Reforming Westminster Chapter II: The Constitutional Reform Process: Commissions, Procedures and the Role of Civil Society A. Lessons from the Reform Process in Belize B. The Challenge of Sustaining Civic Action C. Utilizing New Technologies and the Media D. A New Emphasis for Constitutional Reform Commissions Chapter III: Local Government: Decentralization, Citizen Input and Community Action in Governance and Development A. Citizen-Driven Governance B. Local Government Reform and Constitutional Reform Chapter IV: Regional Integration: Small States and Political Sovereignty in a Global Economy A. Constitutional Requirements of Integration B. Caribbean Courts of Justice Chapter V: Summary of Recommendations A. Proposals for Improving Westminster B. Proposals for Integrating Civil Society into the Political System C. Proposals for Strengthening Civil Society in the Constitutional Reform Process and in Governance D. Proposals with regard to the Constitutional Reform Process E. Proposals regarding Local Government F. Proposals regarding Regional Integration G. Proposals regarding the International Community Executive Summary By 2001, no fewer than 11 nations of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) had embarked on or were considering reform of their constitutions, and -

The Development of Central Banking

Forrest Capie, Charles Goodhart and Norbert Schnadt The development of central banking Book section (Published Version) Original citation: Originally published in Capie, F.; Fischer, S., Goodhart, C. and Schnadt, N. (eds), The future of central banking: the tercentenary symposium of the Bank of England. Cambridge, UK : Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 1-261. ISBN 9780521496346 © 2012 Cambridge University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/39606/ Available in LSE Research Online: March 2012 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. Cambridge Books Online http://ebooks.cambridge.org The Future of Central Banking The Tercentenary Symposium of the Bank of England Forrest Capie, Stanley Fischer, Charles Goodhart, Norbert Schnadt Book DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511983696 Online ISBN: 9780511983696 Hardback ISBN: 9780521496346 Paperback ISBN: 9780521065467 Chapter 1 - The development of central banking pp. 1-261 Chapter DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511983696.002 Cambridge University Press 1 The development of central banking 1 Forrest Capiey Charles Goodhart, Norbert Schnadt 1.1 Introduction On the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the Bank of England there is a natural tendency to look back at the historical record of central banks, to examine their development to the present time, and, more daringly, to speculate about their future.